Apollo 18 (film): Difference between revisions

Dale Arnett (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.4) |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

==Production== |

==Production== |

||

''Apollo 18'' was shot in [[Vancouver]], [[British Columbia]].<ref>{{cite web |

''Apollo 18'' was shot in [[Vancouver]], [[British Columbia]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bcfilmcommission.com/database/rte/files/Jan%2011,%202011%20-%20BCFC%20Film%20List.pdf |title=British Columbia Film Commission Film List: January 11, 2011 |author= |publisher=British Columbia Film Commission |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110928104039/http://www.bcfilmcommission.com/database/rte/files/Jan%2011%2C%202011%20-%20BCFC%20Film%20List.pdf |archivedate=September 28, 2011 }}</ref> However, it has been promoted as a "found footage" film that does not use actors. In an interview with ''[[Entertainment Weekly]]'', [[Dimension Films]] head [[Bob Weinstein]] "balk[ed] at the idea" that the film was a work of fiction, stating that “We didn’t shoot anything; we found it. Found, baby!”<ref>{{cite web|url=http://insidemovies.ew.com/2011/02/25/apollo-18-secret-new-sci-fi-flick-exclusive|title='Apollo 18': Details on the super-secret new sci-fi flick |author=Tim Stack|work=[[Entertainment Weekly]]}}</ref><ref>"We're...not saying that [[mockumentary]] films should be banned. Or [[viral marketing]], for that matter—Apollo 18 has a fairly great Russian cosmonaut viral happening right now. And we're sluts for a good internet puzzle. We just don't need the head of a studio to try and convince us that they found mysterious alien footage on the Moon". From [http://io9.com/#!5774422/are-audiences-sick-of-being-lied-to "Are audiences sick of being lied to?"], by Meredith Woerner, in [[io9]], March 4, 2011</ref> |

||

The [[Science & Entertainment Exchange]] provided a science consultation to the film's production team.<ref>{{cite web|title=Project|url=http://www.scienceandentertainmentexchange.org/projects|publisher=National Academy of Sciences|accessdate=7 July 2011| archiveurl= https://web.archive.org/web/20110726111433/http://www.scienceandentertainmentexchange.org/projects| archivedate=July 26, 2011 <!--DASHBot-->| deadurl= no}}</ref> NASA was also "minimally involved with this picture," but declined to go further with the project.<ref>{{cite news|last=Keegan|first=Rebecca|title=NASA reaches its outer limit|url=http://articles.latimes.com/2011/sep/01/entertainment/la-et-nasa-hollywood-20110901|accessdate=September 14, 2011|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=September 1, 2011}}</ref> |

The [[Science & Entertainment Exchange]] provided a science consultation to the film's production team.<ref>{{cite web|title=Project|url=http://www.scienceandentertainmentexchange.org/projects|publisher=National Academy of Sciences|accessdate=7 July 2011| archiveurl= https://web.archive.org/web/20110726111433/http://www.scienceandentertainmentexchange.org/projects| archivedate=July 26, 2011 <!--DASHBot-->| deadurl= no}}</ref> NASA was also "minimally involved with this picture," but declined to go further with the project.<ref>{{cite news|last=Keegan|first=Rebecca|title=NASA reaches its outer limit|url=http://articles.latimes.com/2011/sep/01/entertainment/la-et-nasa-hollywood-20110901|accessdate=September 14, 2011|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=September 1, 2011}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:49, 8 July 2017

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

| Apollo 18 | |

|---|---|

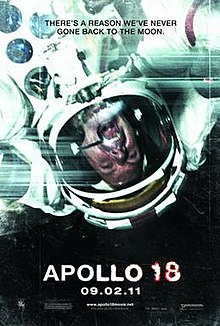

Official film poster | |

| Directed by | Gonzalo López-Gallego |

| Written by | Brian Miller |

| Produced by | Timur Bekmambetov Ron Schmidt |

| Starring | Warren Christie Lloyd Owen Ryan Robbins |

| Cinematography | José David Montero |

| Edited by | Patrick Lussier |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Dimension Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 86 minutes[1] |

| Countries | United States Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5 million[2] |

| Box office | $25.5 million[2] |

Apollo 18 is a 2011 American-Canadian science fiction horror film written by Brian Miller, directed by Gonzalo López-Gallego, and produced by Timur Bekmambetov and Ron Schmidt. After various release date changes, the film was released in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada on September 2, 2011; however, the release dates for other territories vary.[3] The film is López-Gallego's first English-language movie.

The film's premise is that the cancelled Apollo 18 mission actually landed on the moon in December 1974 but never returned, and as a result the United States has never launched another expedition to the Moon. The film is shot in found-footage style, supposedly the lost footage of the Apollo 18 mission that was only recently discovered.

Plot

In December 1974, the crew of the cancelled Apollo 18 mission is informed that it will now proceed as a top secret Department of Defense (DoD) mission disguised as a satellite launch. Commander Nathan Walker, Lieutenant Colonel John Grey, and Captain Ben Anderson are launched toward the Moon to place detectors to alert the United States of any impending ICBM attacks from the USSR.

Grey remains in orbit aboard the Freedom command module while Walker and Anderson land on the moon in the lunar module Liberty. While planting one of the detectors, the pair take moon rock samples. After returning to Liberty, the pair hear noises outside and a camera captures a small rock moving nearby. Houston claims the noises are interference from the ICBM detectors. Anderson finds a rock sample on the floor of Liberty despite having secured the samples. During further lunar exploration they discover footprints that lead them to a bloodstained, functioning Soviet LK lander, and a dead cosmonaut in a nearby crater. Walker queries Houston about the Soviet presence, but he is told only to continue with the mission.

The following day the pair find that the flag they had planted is missing. Their mission complete, the crew prepares to leave, but the launch is aborted when Liberty suffers violent shaking. An inspection reveals extensive damage to Liberty and non-human tracks that Walker cites as evidence of extraterrestrial life. Walker feels something moving inside his spacesuit and is horrified as a spider-like creature crawls across the inside of his helmet. Walker disappears from view and Anderson finds him unconscious outside of Liberty. Walker later denies the events. A wound is discovered on Walker's chest; Anderson removes a moon rock embedded within him. The pair find themselves unable to contact Houston or Grey due to increased levels of interference from an unknown source.

Anderson speculates that the true intention of the ICBM warning devices is to monitor the aliens, and that the devices are the source of the interference, only to discover something has destroyed them when they attempt to switch them off. Walker shows signs of a developing infection and he becomes increasingly paranoid. The mission cameras capture the rock samples moving around in the interior of Liberty, revealing that the aliens are camouflaged as moon rocks. Increasingly delusional, Walker attempts to destroy the cameras within Liberty, but he accidentally damages the system controls, causing Liberty to depressurize. Realizing the Soviet LK is their only source of oxygen, the pair travel towards the LK lander in their lunar rover. Walker causes the vehicle to crash as he runs away, believing he should not leave the moon because of the risk of spreading the infection to Earth.

Anderson awakens and tracks Walker to the crater where they found the cosmonaut. Walker is pulled into the crater by the creatures. Anderson gives chase, but he is confronted by the aliens, and flees to the Soviet LK. Anderson uses its radio to contact USSR Mission Control who connect him to the Department of Defence. The deputy secretary informs Anderson that they cannot allow him to return to Earth, admitting they are aware of the situation and incorrectly believe he is also infected. Anderson manages to contact Grey and they make arrangements for Anderson to return to Freedom. Anderson prepares the lander for launch, but Walker arrives, revealing he had survived the alien encounter earlier. However, he is now completely psychotic and demands to be let in. When Anderson refuses to let him in, he tries to break the lander's window with a hammer. But before Walker can enter the vehicle, he is attacked by a swarm of the creatures inside his helmet, which cause his head to explode, killing him.

Anderson launches, but the DoD warns Grey that Anderson is infected and orders him to abort the rescue or communication will be cut off, without which the CSM will be unable to return to Earth. The lander's engines shut off as it enters orbit, and it is in free fall. Small rocks within the craft float in the air, some of which reveal themselves to be alien creatures. Anderson is attacked and actually infected by the creatures, preventing him from controlling the vehicle. Grey tells Anderson that he is moving too fast as the LK crashes into Freedom killing them both. The space footage ends abruptly.

The footage cuts to before the pilots' mission, showing them having a barbecue with friends and family. The "official" fate of the astronauts is given, describing them as having died in various accidents that left their bodies unrecoverable. An epilogue explains that many of the rock samples returned from the previous Apollo missions are now missing.

Cast

- Warren Christie as Lunar Module Pilot Captain Benjamin "Ben" Anderson

- Lloyd Owen as Commander Nathan "Nate" Walker

- Ryan Robbins as Command Module Pilot Lieutenant Colonel John Grey

- Andrew Airlie as CAPCOM (Thomas Young)

- Michael Kopsa as Deputy Secretary of Defense

Production

Apollo 18 was shot in Vancouver, British Columbia.[4] However, it has been promoted as a "found footage" film that does not use actors. In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Dimension Films head Bob Weinstein "balk[ed] at the idea" that the film was a work of fiction, stating that “We didn’t shoot anything; we found it. Found, baby!”[5][6]

The Science & Entertainment Exchange provided a science consultation to the film's production team.[7] NASA was also "minimally involved with this picture," but declined to go further with the project.[8]

The film is distributed by Dimension Films.[9]

Background

The film concludes with a statement that the Nixon Administration gave away hundreds of moon rocks to foreign dignitaries around the world, and that many of these moon rocks have been lost or stolen. This is actually true; both the Nixon and Ford Administrations gave away 135 Apollo 11 moon rocks and 135 Apollo 17 goodwill moon rocks. The Moon Rock Project, a joint effort of over 1,000 graduate students started at the University of Phoenix in 2002, has helped track down, recover or locate many moon rocks and found that 160 are unaccounted for, lost or destroyed.[10] In 1998, a sting operation, called Operation Lunar Eclipse, made up of personnel from NASA's Office of the Inspector General, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service and U.S. Customs recovered the Honduras Apollo 17 goodwill moon rock, valued at $5 million. In October 2011, NASA agents raided a Denny's restaurant and arrested a 74-year-old woman for attempting to sell a moon rock from Neil Armstrong for $1.7 million on the black market.[11]

Release

Apollo 18 was released on September 2, 2011 in multiple countries. Originally scheduled for February 5, 2010, the film's release date was moved ten times between 2010 and 2011.[3][12][13][14][15][16]

Home media

The film was released December 27, 2011 on DVD, Blu-ray, and online. Special features include an audio commentary with director López-Gallego and editor Patrick Lussier, deleted and alternate scenes and endings, including footage of how the Russian cosmonaut died and 4 alternate deaths of Ben Anderson.

Reception

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2017) |

Apollo 18 has received mostly negative reviews from critics. On the online reviews site Rotten Tomatoes, the film was given a 24% "rotten" score based on 69 reviews, with the consensus "A boring, suspense-free Paranormal Activity rip-off that feels long even at just 90 minutes",[17] and Metacritic, which gives an aggregate score between 0 and 100, gives the film a 24 based on 19 critic reviews, which indicates "generally unfavorable reviews".[18]

Conversely, Fred Topel of CraveOnline gave the film a positive review, saying that the film "will shock you to your core" and that the last 10 minutes "are the most exciting of any summer movie, and without motion capture effects."[19]

Box office

At the end of its run in 2011, Apollo 18 had earned $17,687,709 domestically, plus $7,875,215 overseas for a worldwide gross of $25,562,924 against a $5 million budget, becoming a financial success.[2] In its opening weekend, Apollo 18 screened in 3,328 theaters and opened in number 3, earning $8,704,271, with an average of $2,615 per theater. In its second weekend, the film earned $2,851,349, dropping 62.7%, with an average of $856 per theater, dropping to number 8, but still had a higher total gross at that point over Shark Night 3D, another horror film opening the same weekend as Apollo 18.[citation needed]

See also

- And You and I (song used in film)

- Canceled Apollo missions

- First on the Moon

- Lost Cosmonauts

- Lunarcy!

- Moon landing conspiracy theories in popular culture

- The Case of the Missing Moon Rocks

- Apollo 20 hoax

References

- ^ "Apollo 18 (15)". British Board of Film Classification. August 25, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Apollo 18 (2011)". Box Office Mojo. September 2, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ^ a b "Apollo 18 has its release date moved for the fifth time".

- ^ "British Columbia Film Commission Film List: January 11, 2011" (PDF). British Columbia Film Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tim Stack. "'Apollo 18': Details on the super-secret new sci-fi flick". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ "We're...not saying that mockumentary films should be banned. Or viral marketing, for that matter—Apollo 18 has a fairly great Russian cosmonaut viral happening right now. And we're sluts for a good internet puzzle. We just don't need the head of a studio to try and convince us that they found mysterious alien footage on the Moon". From "Are audiences sick of being lied to?", by Meredith Woerner, in io9, March 4, 2011

- ^ "Project". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Keegan, Rebecca (September 1, 2011). "NASA reaches its outer limit". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ^ "New Apollo 18 Viral Examines Why We Haven't Been Back to the Moon".

- ^ In Search of the Goodwill Moon Rocks: A Personal Account Geotimes Magazine. November 2004.

- ^ NASA agents raid Denny's in undercover sting—after woman, 74, tries to sell moon dust that was gift from Neil Armstrong Mail Online, October 24, 2011.

- ^ McWeeny, Drew (January 7, 2011). "'Apollo 18' game revealing new clues about SF conspiracy thriller". Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- ^ Yamato, Jen (March 25, 2011). "Weinstein Co. Pushes Apollo 18 Release Back to January 2012". Movie Line. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 18 Lands On Another Release Date".

- ^ "Release Date News: 'Apollo 18,' 'Piranha 3DD,' 'Our Idiot Brother' and 'I Don't Know How She Does It'".

- ^ "A Nice Change Of. Pace: 'Apollo 18' And 'Final Destination 5' Move Up".

- ^ "Apollo 18". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 18 Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More at Metacritic". Metacritic.com. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ^ "Review: ‘Apollo 18′", CraveOnline, September 2, 2011

External links

- 2011 films

- 2011 horror films

- 2010s science fiction films

- American science fiction horror films

- American alternate history films

- Canadian alternate history films

- English-language films

- Films about astronauts

- Films about space hazards

- Films about extraterrestrial life

- Films about the Apollo program

- Moon landing conspiracy theories

- Films set in 1974

- Films shot in Vancouver

- Found footage films

- American independent films

- Moon in film

- Canadian films

- Canadian independent films

- 2010s science fiction horror films

- Canadian science fiction films