Impeachment: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

Many mistakenly assume [[Richard Nixon]] was impeached, but he wasn't. While the House Judiciary Committee did approve articles of impeachment against him (by wide margins) and did report those articles to the full House, Nixon resigned prior to House consideration of the impeachment resolutions. Both his impeachment by the House of Representatives and his conviction by the Senate were near certainties; Nixon reportedly decided to resign after being told this by Republican Senator [[Barry Goldwater]]. |

Many mistakenly assume [[Richard Nixon]] was impeached, but he wasn't. While the House Judiciary Committee did approve articles of impeachment against him (by wide margins) and did report those articles to the full House, Nixon resigned prior to House consideration of the impeachment resolutions. Both his impeachment by the House of Representatives and his conviction by the Senate were near certainties; Nixon reportedly decided to resign after being told this by Republican Senator [[Barry Goldwater]]. |

||

Nixon's first vice president, [[Spiro Agnew]], |

Nixon's first vice president, [[Spiro Agnew]], asked the House to impeach him in an effort to forestall indictment and prison on charges of tax evasion and money laundering. House Speaker [[Carl Albert]] refused, and [[Spiro Agnew|Agnew]] resigned as part of a plea bargin on Oct. 10, 1973. |

||

==Republic of Ireland== |

==Republic of Ireland== |

||

Revision as of 12:50, 4 November 2006

- This is about a step in the removal of a public official; for challenging a witness in a legal proceeding, see witness impeachment.

In the constitutions of several countries, impeachment is the first of two stages in a specific process for a legislative body to remove a government official without that official's agreement.

Impeachment occurs so rarely that the term is often misunderstood [citation needed]. A typical misconception is to confuse it with involuntary removal from office; in fact it is only the legal statement of charges, parallelling an indictment in criminal law. An official who is impeached faces a second legislative vote (whether by the same body or another), which determines conviction, or failure to convict, on the charges embodied by the impeachment. Most constitutions require a supermajority to convict.

One tradition of impeachment has its origins in the law of England and Wales, where the procedure last took place in 1806. Impeachment exists under constitutional law in many nations around the world, including the United States, India, Brazil, Russia, the Philippines, and the Republic of Ireland.

Etymologically, the word "impeachment" derives from Latin roots expressing the idea of becoming caught or entrapped, and has analogues in the modern French verb empêcher (to prevent) and the modern English impede. Medieval popular etymology also associated it (wrongly) with derivations from the Latin impetere (to attack). (In its more frequent and more technical usage, impeachment of a person in the role of a witness is the act challenging the honesty or credibility of that person.)

The process should not be confused with recall election. A recall election is usually initiated by voters and can be based on "political charges", for example mismanagement, whereas impeachment is initiated by a constitutional body (usually a legislative body) and is based on criminal charges. The process of removing the official is also different.

United Kingdom

Procedure

In the United Kingdom, the House of Commons holds the power of initiating an impeachment. Any member may make accusations of high treason or high crimes and misdemeanours. The member must support the charges with evidence and move for impeachment. If the Commons carries the motion, the mover receives orders to go to the bar at the House of Lords and to impeach the accused "in the name of the House of Commons, and all the commons of the United Kingdom."

The mover must tell the Lords that the House of Commons will, in due time, exhibit particular articles against the accused, and make good the same. The Commons then usually select a committee to draw up the charges and create an "Article of Impeachment" for each. (In the case of Warren Hastings, however, the drawing up of the articles preceded the formal impeachment.) Once the committee has delivered the articles to the Lords, replies go between the accused and the Commons via the Lords. If the Commons have impeached a peer, the Lords take custody of the accused, otherwise custody goes to Black Rod. The accused remains in custody unless the Lords allow bail. The Lords set a date for the trial while the Commons appoints managers, who act as prosecutors in the trial. The accused may defend by counsel.

The House of Lords hears the case,, with the Lord Chancellor presiding (or the Lord High Steward if the impeachment relates to a peer accused of high treason.) The hearing resembles an ordinary trial: both sides may call witnesses and present evidence. At the end of the hearing the Lord Chancellor puts the question on the first article to each member in order of seniority, commencing with the most junior peer, and ending with himself, and after all have voted, proceeds to deal with any remaining articles similarly. Upon being called, a Lord must rise and declare upon his honour, "Guilty" or "Not Guilty". After voting on all of the articles has taken place, and if the Lords find the defendant guilty, the Commons may move for judgment; the Lords may not declare the punishment until the Commons have so moved. The Lords may then provide whatever punishment they find fit, within the law. A Royal Pardon cannot excuse the defendant from trial, but a Pardon may reprieve a convicted defendant.

History

Parliament has held the power of impeachment since mediæval times. Originally, the House of Lords held that impeachment could only apply to members of the peerage (nobles), as the nobility (the Lords) would try their own peers, while commoners ought to try their peers (other commoners) in a jury. However, in 1681, the Commons declared that they had the right to impeach whomsoever they pleased, and the Lords have respected this resolution.

After the reign of Edward IV, impeachment fell into disuse, the bill of attainder becoming the preferred form of dealing with undesirable subjects of the Crown. However, during the reign of James I and thereafter, impeachments became more popular, as they did not require the assent of the Crown, while bills of attainder did, thus allowing Parliament to resist royal attempts to dominate Parliament. The most recent cases of impeachment dealt with Warren Hastings, Governor-General of India between 1773 and 1786 (impeached in 1788; the Lords found him not guilty in 1795), and Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, First Lord of the Admiralty, in 1806 (acquitted). The last attempted impeachment occurred in 1848, when David Urquhart accused Lord Palmerston of having signed a secret treaty with Imperial Russia and of receiving monies from the Tsar. Palmerston survived the vote in the Commons; the Lords did not hear the case.

Impeachment in modern politics

The procedure has, over time, become rarely used and some legal authorities (such as Halsbury's Laws of England) consider it to be probably obsolete. The principles of "responsible government" require that the Prime Minister and other executive officers answer to Parliament, rather than to the Sovereign. Thus the Commons can remove such an officer through a motion of no confidence without a long, drawn-out impeachment. However, it is argued by some that the remedy of impeachment remains as part of British constitutional law, and that legislation would be required to abolish it. Furthermore, impeachment as a means of punishment for wrongdoing, as distinct from being a means of removing a minister, remains a valid reason for accepting that it continues to be available, at least in theory.

In April 1977 the Young Liberals' annual conference unanimously passed a motion to call on the Liberal leader (David Steel) to move for the impeachment of Ronald King Murray QC, the Lord Advocate. Mr. Steel did not call the motion but Murray (now Lord Murray, a former Senator of the College of Justice of Scotland) agrees that the Commons still have the right to initiate an impeachment motion. On 25 August 2004, Plaid Cymru MP Adam Price announced his intention to move for the impeachment of Tony Blair for his role in involving Britain in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In response Peter Hain, the Commons Leader, insisted that impeachment was obsolete, given modern government's responsibility to parliament. Ironically, Peter Hain had served as president of the Young Liberals when they called for the impeachment of Mr. Murray in 1977.

In 2006 General Sir Michael Rose revived the call for the impeachment of the United Kingdom's Prime Minister Tony Blair for leading the country into the invasion of Iraq in 2003 under false pretenses. For similar reasons, there is a loosely formed movement to impeach George W. Bush as President of the United States.

United States

In the United States, impeachment can occur both at the federal and state level. At the federal level, different standards apply when the impeachment involves a member of the executive branch or of the judiciary (and dispute currently exists over the use of impeachment against members of the legislative branch.) For the executive branch, only those who have allegedly committed "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors" may be impeached. Although treason and bribery are obvious, the Constitution is silent on what constitutes a "high crime or misdemeanor." Several commentators have suggested that Congress alone may decide for itself what constitutes an impeachable offense. The standard for impeachment among the judiciary is much broader. Article III of the Constitution states that judges remain in office "during good behavior," implying that Congress may remove a judge for bad behavior. The standard for impeachment of members of the legislature is/would be the same as the Executive standard, "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors."

The central question regarding the Constitutional dispute about the impeachment of members of the legislature is this: Are members of Congress "officers" of the United States? The Constitution grants to the House the power to impeach "The President, the Vice President, and all civil Officers of the United States." Many believe firmly that Members of Congress are not "officers of the United States." Source (pdf) (Navigate to page 7) Many others, however, believe that Members are civil Officers and are subject to impeachment. The House of Representatives did impeach a Senator once, Senator William Blount. The Senate expelled Senator Blount and, after initially hearing his impeachment, dismissed the charges for lack of jurisdiction. Left unsettled was the question "Are members of Congress civil officers of the United States?" In modern times, expulsion has become the preferred (albeit rare) method of dealing with errant Members of Congress, as each House has the authority to expel their own members—without involving the other chamber, as impeachment would require.

The impeachment procedure is in two steps. The House of Representatives must first pass "articles of impeachment" by a simple majority. (All fifty state legislatures as well as the District of Columbia city council may also pass articles of impeachment against their own executives). The articles of impeachment constitute the formal allegations. Upon their passage, the defendant has been "impeached."

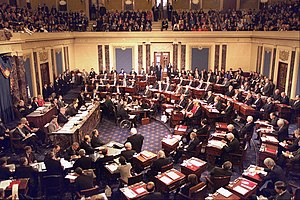

Next, the Senate tries the accused. In the case of the impeachment of a President, the Chief Justice of the United States presides over the proceedings. Otherwise, the Vice President, in his capacity as President of the Senate, or the President pro tempore of the Senate presides. This may include the impeachment of the Vice President him- or herself, although legal theories suggest that allowing a person to be the judge in the case where she or he was the defendant wouldn't be permitted. If the Vice President did not preside over an impeachment, the duties would fall to the President Pro Tempore.

In order to convict the accused, a two-thirds majority of the senators present is required. Conviction automatically removes the defendant from office. Following conviction, the Senate may vote to further punish the individual by barring them from holding future federal office (either elected or appointed). Despite a conviction by the Senate, the defendant remains liable to criminal prosecution. It is possible to impeach someone even after the accused has vacated their office in order to disqualify the person from future office or from certain emoluments of their prior office (such as a pension.) If a two-thirds majority of the senators present does not vote "Guilty" on one or more of the charges, the defendant is acquitted and no punishment is imposed.

Congress regards impeachment as a power to be used only in extreme cases; the House has initiated impeachment proceedings only 62 times since 1789 (most recently President Clinton), and only the following 17 federal officers have been impeached:

- two presidents:

- Andrew Johnson was impeached in 1868 after violating the then-newly created Tenure of Office Act. Johnson was acquitted of all charges by a single vote in the Senate.

- Bill Clinton was impeached on December 19, 1998 by the House of Representatives on grounds of perjury to a grand jury (by a 228–206 vote) and obstruction of justice (by a 221–212 vote). Two other articles of impeachment failed — a second count of perjury in the Jones case (by a 205–229 vote), and one accusing Clinton of abuse of power (by a 148–285 vote). He was acquitted by the Senate.

- one cabinet officer, William W. Belknap (Secretary of War). He resigned before his trial, and was later acquitted. Allegedly most of those who voted to acquit him believed that his resignation had removed their jurisdiction.

- one Senator, William Blount (though the Senate had already expelled him and it may have been illegal, see above).

- Associate Justice Samuel Chase in 1804. He was acquitted.

- twelve other federal judges, including Alcee Hastings, who was impeached and convicted for allegedly taking over $150,000 in bribe money in exchange for sentencing leniency. Interestingly, the Senate did not bar Hastings from holding future office, and Hastings currently serves as a Democratic member of the House of Representatives from South Florida. Hastings has been mentioned as a possible chair of the House Armed Services committee in the event the Democrats regain control of the House during the midterm elections.

Many mistakenly assume Richard Nixon was impeached, but he wasn't. While the House Judiciary Committee did approve articles of impeachment against him (by wide margins) and did report those articles to the full House, Nixon resigned prior to House consideration of the impeachment resolutions. Both his impeachment by the House of Representatives and his conviction by the Senate were near certainties; Nixon reportedly decided to resign after being told this by Republican Senator Barry Goldwater.

Nixon's first vice president, Spiro Agnew, asked the House to impeach him in an effort to forestall indictment and prison on charges of tax evasion and money laundering. House Speaker Carl Albert refused, and Agnew resigned as part of a plea bargin on Oct. 10, 1973.

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland formal impeachment can apply only to the President. Article 12 of the Constitution of Ireland provides that, unless judged to be "permanently incapacitated" by the Supreme Court, the president can only be removed from office by the houses of the Oireachtas (parliament) and only for the commission of "stated misbehaviour". Either house of the Oireachtas may impeach the president, but only by a resolution approved by a majority of at least two-thirds of its total number of members; and a house may not consider a proposal for impeachment unless requested to do so by at least thirty of its number.

Where one house impeaches the president, the remaining house either investigates the charge or commissions another body or committee to do so. The investigating house can remove the president if it decides, by at least a two-thirds majority of its members, both that she is guilty of the charge of which she stands accused, and that the charge is sufficiently serious as to warrant her removal. To date no impeachment of an Irish president has ever taken place. The president holds a largely ceremonial office, the dignity of which is considered important, so it is likely that a president would resign from office long before undergoing formal conviction or impeachment.

The Republic's constitution and law also provide that only a joint resolution of both houses of the Oireachtas may remove a judge. Although often referred to as the 'impeachment' of a judge, this procedure does not technically involve impeachment.

Other jurisdictions

- Austria: The Austrian Federal President can be impeached by the Federal Convention (Bundesversammlung) before the Constitutional Court. The constitution also provides for the recall of the president by a referendum. Neither of these courses has ever been taken.

- Brazil: The President of Federative Republic of Brazil can be impeached. This happened to Fernando Collor de Mello, due to evidences of bribery and misappropriation.

- Germany: The Federal President of Germany can be impeached both by the Bundestag and by the Bundesrat for willfully violating German law. Once the Bundestag or the Bundesrat impeaches the president, the Federal Constitutional Court decides wether the President is guilty as charged and, if this is the case, whether to remove him or her from office. No such case has yet occurred, not the least beacause the President's functions are mostly ceremonial and he or she seldomly makes controversial decisions. The Federal Constitutional Court also has the power to remove federal judges from office for willfully violating core principles of the federal constitution or a state constitution.

- Norway: Members of government, representatives of the national assembly (Stortinget) and Supreme Court judges can be impeached for criminal offences tied to their duties and committed in office, according to the Constitution of 1814, §§ 86 and 87. The procedural rules were modelled on the US rules and are quite similar to them. Impeachment has been used 8 times since 1814, last in 1927. Many argue that impeachment has fallen into desuetude.

- Russia: The President of Russia can be impeached if both the State Duma (which initiates the impeachment process through the formation of a special investigation committee) and the Federation Council of Russia vote by a two-thirds majority in favor of impeachment and, additionally, the Supreme Court finds the President guilty of treason or a similarly heavy crime against the nation. In 1995-1999, the Duma made several attempts to impeach then-President Boris Yeltsin, but they never had a sufficient amount of votes for the process to reach the Federation Council.

- Taiwan: Officials can be impeached by a two-thirds vote in the Legislative Yuan together with an absolute majority in a referendum. President Chen Shui-bian is currently being impeached.

Presidents who were removed from office following impeachment

- Fernando Collor de Mello, president of Brazil, was impeached in 1992, after the Congress rejected his resignation letter.

- Carlos Andrés Pérez, president of Venezuela, was impeached in 1993.

- Raúl Cubas Grau, president of Paraguay, was impeached in 1999.

- Rolandas Paksas, president of Lithuania, was impeached on April 6, 2004.

See also

- Impeachment in the United States

- Movement to impeach George W. Bush

- SourceWatch Article on The Case for Impeachment of President George W. Bush

Bold text