2018 Pacific hurricane season: Difference between revisions

→Seasonal summary: update ACE |

→Hurricane Olivia: parcial update,need fixes |

||

| Line 402: | Line 402: | ||

{{Infobox hurricane current |

{{Infobox hurricane current |

||

|name=Hurricane Olivia |

|name=Hurricane Olivia |

||

|category= |

|category=cat3 |

||

|type=hurricane |

|type=hurricane |

||

|time=8:00 a.m. [[Pacific Time Zone|PDT]] (15:00 [[Coordinated Universal Time|UTC]]) September 5 |

|time=8:00 a.m. [[Pacific Time Zone|PDT]] (15:00 [[Coordinated Universal Time|UTC]]) September 5 |

||

| Line 410: | Line 410: | ||

|within_units=20 [[nautical mile|nm]] |

|within_units=20 [[nautical mile|nm]] |

||

|distance_from=About 900 mi (1,445 km) SW of [[Baja California]] |

|distance_from=About 900 mi (1,445 km) SW of [[Baja California]] |

||

|1sustained= |

|1sustained=105 kt (110 mph; 175 km/h) |

||

|gusts=115 kt (130 mph; 215 km/h) |

|gusts=115 kt (130 mph; 215 km/h) |

||

|pressure= |

|pressure=959 [[mbar]] ([[Pascal (unit)|hPa]]; 28.56 [[Inches of Mercury|inHg]]) |

||

|movement=[[Points of the compass|W]] at 11 kt (13 mph; 20 km/h) |

|movement=[[Points of the compass|W]] at 11 kt (13 mph; 20 km/h) |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 12:04, 6 September 2018

| 2018 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 10, 2018 |

| Last system dissipated | Season ongoing |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Lane |

| • Maximum winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 922 mbar (hPa; 27.23 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 17, 1 unofficial |

| Total storms | 15, 1 unofficial |

| Hurricanes | 9 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 6 |

| Total fatalities | 5 total |

| Total damage | > $10.5 million (2018 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 2018 Pacific hurricane season is an ongoing event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation. The season officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the central Pacific; they will both end on November 30.[1] These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Pacific basin, as illustrated when the first tropical depression formed on May 10. The first named storm of the season, Hurricane Aletta, formed on June 6. Hurricane Bud formed three days later and made landfall in Baja California Sur. Tropical Storm Carlotta stalled offshore the Mexican coastline causing minor damage. Hurricane Hector became the first tri-basin crosser since 2014. In late August, Hurricane Lane became the first Category 5 Pacific hurricane since Patricia of 2015. Lane went on to drop torrential amounts of rainfall over Hawaii, becoming the state's wettest tropical cyclone on record and the second-wettest overall in the United States.

Seasonal forecasts

| Record | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (1981-2010): | 15.4 | 7.6 | 3.2 | [2] | |

| Record high activity: | 1992: 27 | 2015: 16 | 2015: 11 | [3] | |

| Record low activity: | 2010: 8 | 2010: 3 | 2003: 0 | [3] | |

| Date | Source | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| May 24, 2018 | NOAA | 14–20 | 7–12 | 3–7 | [4] |

| May 25, 2018 | SMN | 18 | 6 | 4 | [5] |

| Area | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref | |

| Actual activity: | EPAC | 15 | 9 | 6 | |

| Actual activity: | CPAC | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Actual activity: | 15 | 9 | 6 | ||

On May 24, 2018, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration released its annual forecast, predicting a 80% chance of a near- to above-average season in both the Eastern and Central Pacific basins, with a total of 14–20 named storms, 7–12 hurricanes, and 3–7 major hurricanes.[4] On May 25, the Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN) issued its first forecast for the season, predicting a total of 18 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes to develop.[5]

Seasonal summary

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy index for the 2018 Pacific hurricane season, as of 09:00 UTC September 6, is 196.5225 units (115.1525 units for the eastern Pacific and 81.37 units for the central Pacific).[nb 1]

The 2018 season began with the formation of Tropical Depression One-E on May 10, five days prior to the official start. June was an extraordinarily active month in the basin, breaking the record for number of tropical cyclones (six), as well as tying the records for number of named storms (five) and major hurricanes (two).[6] Fabio's intensification into a tropical storm on July 1 marked the earliest date of a season's sixth named storm, beating the previous record of July 3 set in both 1984 and 1985.[7] Activity abruptly slowed thereafter, with only three tropical cyclones forming during the month of July,[8] one of which continued on to intensify into Hurricane Hector in August, which became the third major hurricane of the season. In August, activity increased dramatically, with Tropical Storm Ileana and Hurricane John forming just a day apart on August 4 and August 5, respectively, followed by Tropical Storm Kristy two days later. Hurricane Lane formed in mid-August and became the first Category 5 storm of the season, and the wettest tropical cyclone on record in Hawaii since Hiki in 1950. Hurricanes Miriam and Norman soon followed, forming in late August, with Norman becoming the fifth major hurricane and fourth Category 4 hurricane of the season.[citation needed]

Systems

Tropical Depression One-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 10 – May 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

In early May, a westward-tracking trough or tropical wave embedded in the monsoon trough interacted with a convectively-coupled Kelvin wave. This interaction led to a large area of shower and thunderstorm activity well southwest of Mexico,[9] which the National Hurricane Center began monitoring for tropical cyclone formation on May 7.[10] The disturbance organized over the next 48 hours but lacked a well-defined center needed for classification;[11] by late on May 9, environmental conditions were becoming less favorable for development.[12] In spite of this, an increase in convection and formation of a well-defined circulation led to the designation of the season's first tropical depression at 21:00 UTC on May 10.[13] The system failed to intensify after formation and, owing to strong westerly wind shear, ultimately degenerated into a remnant low by 18:00 UTC on May 11.[14]

Hurricane Aletta

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 6 – June 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 943 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave departed western Africa on May 22, moving inconspicuously across the Atlantic and failing to develop convection until it was south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec on June 3. Following the formation of a well-defined center, the system was upgraded to a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on June 6. It intensified into Tropical Storm Aletta six hours later. Subtropical ridging over the United States directed the system west-northwest, while ideal environmental conditions allowed Aletta to reach hurricane strength around 18:00 UTC on June 7. A period of rapid deepening ensued shortly thereafter, with maximum winds increasing from 75 mph (120 km/h) to 140 mph (220 km/h) within an 18-hour period.[15] At peak, the hurricane was characterized by a distinct eye embedded within cloud tops colder than -70 °C (-94 °F).[16] A track into cooler waters and a more stable air mass caused Aletta to weaken as quickly as it intensified, falling from Category 4 strength to a tropical storm within 30 hours. After losing its associated deep convection, the system degenerated to a remnant low around 12:00 UTC on June 11. The low meandered for several days, before dissipating early on June 16.[15]

Hurricane Bud

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 9 – June 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); 948 mbar (hPa) |

A broad area of disturbed weather formed west of Costa Rica on June 5 in association with a westward-moving tropical wave.[17] Gradual organization occurred as the wave tracked generally westward across the eastern Pacific Ocean. On June 9, the disturbance developed a well-defined surface circulation, leading to the classification of a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC.[18] Six hours later, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Bud.[19] A mid-level ridge to the storm's north directed it on a northwest heading for several days,[20] while favorable environmental conditions led to rapid intensification. Bud attained hurricane strength by 21:00 UTC on June 10,[21] and continued intensification up to its peak as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) around 06:00 UTC on June 12.[22] The effects of cold water upwelling prompted a rapid weakening trend shortly after peak, with Bud falling to a tropical storm by 12:00 UTC on June 13.[23] The system made landfall near Cabo San Lucas with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h), shortly after 00:00 UTC on June 15, before progressing into the Gulf of California,[24] where it ultimately degenerated to a remnant low around 21:00 UTC that day.[25]

Tropical Storm Carlotta

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 14 – June 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

A broad area of low pressure formed south of Mexico on June 12,[26] organizing into the season's fourth tropical depression by 21:00 UTC on June 14 and further into Tropical Storm Carlotta around 18:00 UTC on June 15.[27][28] Initial forecasts showed the storm only slightly intensifying before moving ashore the coastline of Mexico;[29] instead, Carlotta stalled just offshore and strengthened to attain peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) as it established an inner core and eye.[30] Interaction between the system's eyewall and land prompted a swift weakening trend as it paralleled the Mexican shoreline, and Carlotta fell to tropical depression intensity by 18:00 UTC on June 17, before degenerating to a remnant low around 03:00 UTC on June 19.[31][32]

Tropical Storm Daniel

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 24 – June 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

Late on June 21, the NHC began monitoring a surface trough and its associated disorganized convection several hundred miles southwest of Baja California. Environmental conditions were expected to be marginally conducive for development as it moved north-northwest.[33] Convection began to show signs of organization early on June 23,[34] and this process led to the formation of a tropical depression by 03:00 UTC on the next morning, as spiral bands wrapped into the storm's well-defined center.[35] At 15:00 UTC on June 24, the depression was upgraded to a tropical storm and was assigned the name Daniel.[36] At 18:00 UTC on June 24, Tropical Storm Daniel reached peak intensity with sustained winds of 45 mph.[37] At 15:00 UTC on June 25, Daniel began to weaken as it moved over seas cooler than 25 °C (77 °F).[38] The system weakened to a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC that day.[39] At 15:00 UTC on June 26, Daniel degenerated into a remnant low, as it lost all convection and was reduced to a swirl of low-level clouds.[40]

Tropical Storm Emilia

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 27 – July 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

On June 23, the NHC noted the potential for tropical cyclogenesis from a tropical wave crossing over Costa Rica. Environmental conditions were expected to be conducive for development as it moved westward.[41] The system then steadily organized over warm waters, developing into Tropical Depression Six-E at 18:00 UTC June 27, about 480 miles (770 km) southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico.[42] It gradually strengthened into Tropical Storm Emilia at 12:00 UTC on June 28.[42] At 12:00 UTC on June 29, Emilia reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h); however, it was then subject to strong wind shear.[42] The shear took its toll on Emilia, and by 12:00 UTC the next day, it weakened into a tropical depression.[42] Finally, at 00:00 UTC on July 2, Emilia degenerated into a remnant low, as it lost its convection and was reduced to a swirl of clouds.[42]

Hurricane Fabio

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 30 – July 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); 964 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC first noted the potential for tropical cyclogenesis from a tropical wave crossing over Honduras and Nicaragua at 18:00 UTC on June 24.[43] Subsequent development was expected of the system as it moved westward. It steadily organized over warm waters and transitioned into Tropical Depression Seven-E at 21:00 UTC June 30, 490 miles (790 km) southwest of Acapulco, Mexico.[44] The system gradually strengthened into Tropical Storm Fabio at 09:00 UTC on July 1.[45] With SSTs of 30 °C (86 °F) and almost no wind shear, Fabio began to intensify, quickly strengthening into a hurricane by 15:00 UTC on July 2.[46] Initially, forecasters at the NHC predicted that Fabio would intensify further and become a major hurricane, although it failed to do so and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h), just shy of major hurricane status.[47] Afterward, Fabio began to rapidly weaken as it moved over cooler waters. At 15:00 UTC on July 6, Fabio degenerated into a remnant low as it lost its convection while located 1,285 miles (2,065 km) off the coast of the Baja Peninsula.[48]

Tropical Storm Gilma

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 26 – July 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

On July 18, the NHC forecast the development of an area of low pressure over the east Pacific Ocean within the next few days.[49] A weak area of low pressure developed several hundred miles south-southeast of the Gulf of Tehuantepec on July 22. Little development occurred over the next few days as the low moved northwestward across the Pacific Ocean. However, shower and thunderstorm activity associated with the low began to quickly organize on July 26, leading to the classification of a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC on July 26.[50] At 09:00 UTC the following day, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Gilma.[51] However, northwesterly wind shear soon exposed the center of circulation, causing Gilma to weaken to a tropical depression just twelve hours later.[52] At 21:00 UTC on July 29, the system degenerated into a remnant low as it had lacked organized deep convection for 12 hours.[53]

Tropical Depression Nine-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 26 – July 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1008 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began monitoring a disorganized area of low pressure in the deep tropical Pacific Ocean on July 24 for tropical cyclone development.[54] Gradual organization ensued as the low moved westward, and by July 26, it had organized sufficiently to be classified as a tropical depression.[55] The tropical depression failed to organize, however, and the center soon became difficult to locate on satellite imagery.[56] After having lasted less than a day as a tropical cyclone, the depression opened up into a trough, as it became embedded within the Intertropical Convergence Zone at 12:00 UTC on July 27.[57]

Hurricane Hector

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 31 – August 13 (Exited basin) |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-min); 936 mbar (hPa) |

Late on July 26, the NHC noted the development of an area of low pressure that was forecast to form a couple hundred miles west-southwest of Mexico.[58] A broad area of low pressure formed several hundred miles south-southeast of Acapulco, Mexico, at 12:00 UTC on July 28.[59] The system gradually developed into a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC on July 31.[60] The depression quickly organized, developing a more defined center and spiral banding, and at 03:00 UTC on August 1, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Hector.[61] Hector further strengthened and became a hurricane at 14:00 UTC on August 2.[62] Afterward, the small hurricane rapidly strengthened, becoming a strong Category 2 hurricane just six hours later.[63] However, the eye became clouded and ill-defined shortly afterward, while the storm underwent an eyewall replacement cycle, and Hector's intensification halted momentarily, as northeasterly shear and dry air impinged on the system, weakening the system back to a Category 1 hurricane.[64] However, the hurricane quickly intensified yet again, and restrengthened back into a Category 2 hurricane, and later to a Category 3 hurricane, making it the third major hurricane of the season. A strong convective band soon wrapped into Hector's central dense overcast (CDO), strengthening it to a Category 4 major hurricane.[65] On the next morning, a shrinking CDO weakened Hector back into a Category 3 storm.[66] In the following hours, Hector underwent another eyewall replacement cycle and was set to weaken thereafter. However, after the completion of the eyewall replacement cycle, Hector rapidly intensified back to a high-end Category 4 storm on August 6. At 09:00 UTC on August 8, Hector weakened to a category 3 hurricane. At 21:00 UTC, the CPHC reported that Hector was passing about 200 miles (320 km) south of the Big Island with winds of 115 mph. At the same time, Hector began a third eyewall replacement cycle. By 09:00 UTC on August 9, Hector completed the eyewall replacement cycle.

By 15:00 UTC on the same day, Hector began to intensify once again, as it moved due west. At 21:00 UTC on August 10, Hector reached its secondary peak intensity with winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) as it began to turn west-northwest. On August 11, Hector began another weakening trend as increasing wind shear began to take a toll on the system. By this time, the hurricane set a record for the longest consecutive duration as a major hurricane in the northeastern Pacific. Late on August 11, Hector weakened below major hurricane strength due to increasing wind shear, a status it had held for nearly eight days. Hector weakened to Category 1 status on August 12. On August 13 at 15:00 UTC, Hector crossed the International Date Line as a tropical storm.

Tropical Storm Ileana

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 4 – August 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave entered the eastern Pacific Ocean on August 3, where the NHC began to monitor the system for tropical development.[67] Although the system was initially disorganized, it rapidly organized over the next two days, and on August 4 it developed into a tropical depression while located south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec.[68] The depression continued to organize that night through the next day, and at 21:00 UTC on August 5, the system strengthened into Tropical Storm Ileana.[69] After strengthening to peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h), Ileana weakened as it began to feel the influence of the much larger Hurricane John, with the two systems experiencing the Fujiwhara effect. On August 7, the small circulation of Ileana dissipated, as the storm was absorbed by John.[70]

Heavy rain in Guerrero resulted in three deaths, while rip currents caused an additional fatality along the coast of Acapulco.[71]

Hurricane John

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 5 – August 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 969 mbar (hPa) |

On July 29, the NHC began forecasting the development of an area of low pressure that was expected to form several hundred miles off the Mexican coast.[72] A broad area of low pressure formed several hundred miles south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec on August 2.[73] Gradual organization occurred as the low moved slowly west-northwestward, and at 21:00 UTC on August 5, the low had organized sufficiently to be classified as the season's twelfth tropical depression.[74] The depression quickly strengthened into Tropical Storm John six hours later.[75] Amid very favorable environmental conditions, John rapidly intensified, and by 21:00 UTC on August 6, John had become the fifth hurricane of the season, and soon began to interact with Tropical Storm Ileana to the east, due to the Fujiwhara effect.[76] On August 7, Hurricane John absorbed the smaller Tropical Storm Ileana, while continuing to strengthen.[70] At 15:00 UTC August 7, John reached peak intensity with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h).[77] However, John began to move over cooler waters and began to weaken. The cyclone fell to a Category 1 by 15:00 UTC August 8, and to tropical storm status by 09:00 UTC August 9, until it finally degenerated into a remnant low at 15:00 UTC on August 10.[78]

Although John never made landfall, it produced high surf along the coastlines of Baja California and Southern California.[79]

Tropical Storm Kristy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 7 – August 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 991 mbar (hPa) |

An area of disturbed weather formed south of Mexico on August 2,[80] the NHC began monitoring the disturbance for potential tropical development. The system lingered for days without developing as it tracked generally towards the west, until it gained enough organization to be classified as Tropical Depression Thirteen-E at 05:00 UTC on August 7.[81] The depression eventually developed into Tropical Storm Kristy at 09:00 UTC later that day.[82] Kristy gradually strengthened over the next few days, and at 03:00 UTC on August 10, it attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h), just short of hurricane status.[83] As Kristy moved over cooler waters, it gradually weakened, degenerating into a remnant low at 15:00 UTC on August 11.[84]

Hurricane Lane

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 15 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min); 922 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed well southwest of Baja California around 03:00 UTC on August 15, from an area of disturbed weather the NHC had been monitoring for days.[85] Steered due west amid favorable environmental conditions, the system intensified into Tropical Storm Lane by 15:00 UTC on the next day,[86] and further strengthened to a hurricane around 03:00 UTC on August 17 as an eye became apparent.[87] Following the formation of an inner core, Lane began a period of rapid intensification that brought the system to its initial peak intensity as a Category 4 hurricane early on August 18.[88] It crossed into the Central Pacific thereafter, where strong westerly wind shear caused a substantial degradation in satellite presentation.[89] Upper-level winds gradually slackened, allowing Lane to regain Category 4 intensity late on August 20.[90] Despite forecasts calling for the storm to weaken, Lane continued to strengthen. By 04:30 UTC on August 22, data from a reconnaissance aircraft measured maximum 1-minute sustained winds near 160 mph (260 km/h), and Lane was upgraded to a Category 5 hurricane as it maintained a distinct eye surrounded by deep convection.[91][92][93] However, shear increased weakening Lane to a Category 4 as it traveled towards Hawaii, guided by a strengthening ridge.[94] Rapid weakening ensued thereafter, weakening Lane from a Category 2 to a tropical storm in 6 hours due to 35 to 40 knots of wind shear impacting Lane's core convection.[95] Early on August 26, Lane made the turn west that it had been predicted to make as it was embedded in the trade winds.[96] At 15:00 UTC August 26, Lane weakened into a tropical depression as its low level center was nearly entirely exposed.[97] However, at 15:00 UTC August 27, Lane re-intensified into a tropical storm as a convective bursts partially covered the low level center.[98] However, this re-intensification would be short lived as 18 hours later Lane diverted back into a tropical depression as its low level circulation was once again exposed due to constant wind shear.[99] Finally, at 3:00 UTC August 29, Lane degenerated into a remnant low as its circulation became elongated and cloud tops near the center warmed and moved away from the center.[100]

Hurricane Miriam

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 26 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 974 mbar (hPa) |

At 21:00 UTC on August 22, forecasters at the NHC forecasted that an area of low pressure could form several hundred miles southwest of the Baja California Sur.[101] Shortly afterward, on August 24, a trough of low pressure formed where the NHC predicted where it would be, predictions said that gradual development would be possible of the system.[102] Gradual development ensued and a tropical depression formed at 9:00 UTC August 26.[103] At 15:00 UTC the same day, the depression intensified into a tropical storm, where it was given the name Miriam.[104] The system gradually intensified and at 21:00 UTC on August 29, Miriam intensified into a hurricane.[105] At 0:00 UTC on August 30, Miriam entered the Central Pacific where responsibility was handed over to the CPHC. At 12:00 UTC on August 31, Miriam intensified to attain its peak intensity as a Category 2 hurricane.[106] Soon thereafter, Miriam began to be affected by wind shear, weakening into a Category 1 hurricane on August 31.[107][108] Late on September 2, Miriam degenerated into a remnant low, due to the strong wind shear.

Hurricane Norman

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

Current storm status Category 3 hurricane (1-min mean) | |||

| |||

| As of: | 5:00 p.m. HST September 5 (03:00 UTC September 6) | ||

| Location: | 20°00′N 149°12′W / 20.0°N 149.2°W ± 15 nm About 385 mi (620 km) E of Hilo, Hawaii About 570 mi (915 km) E of Honolulu, Hawaii | ||

| Sustained winds: | 105 kt (120 mph; 195 km/h) (1-min mean) gusting to 120 kt (140 mph; 225 km/h) | ||

| Pressure: | 960 mbar (hPa; 28.35 inHg) | ||

| Movement: | WNW at 8 kt (9 mph; 15 km/h) | ||

| See more detailed information. | |||

Hurricane Norman originated from a broad area of low pressure that formed several hundred miles south-southwest of Acapulco, Mexico on August 25.[109] Traveling west-northwest,[110] the system coalesced into a tropical depression by at 15:00 UTC on August 28 while situated approximately 420 miles (675 km) south-southwest of the southern tip of Baja California.[111] A subtropical ridge steered the system west for several days.[112] Early on August 29, the depression intensified into a tropical storm and received the name Norman.[113] Favorable environmental conditions enabled quick intensification, and the system achieved hurricane strength early on August 30.[114] Rapid intensification ensued throughout the day, culminating with Norman attaining its peak intensity at 15:00 UTC, with sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a central pressure of of 937 mbar (27.67 inHg).[115][116][117] During a 24-hour period, the hurricanes winds increased by 80 mph (130 km/h), the largest such increase since Hurricane Patricia in 2015.[118]

The combination of an eyewall replacement cycle and increasing wind shear induced weakening beginning on August 31. At 03:00 UTC on August 31, Norman turned to the west-southwest due to a deep-layer ridge to the north.[119] [120][121] Norman fell to Category 2 status for a period,[122] before unexpectedly rapidly intensifying back to a Category 4 hurricane on September 2. The storm attained a secondary peak with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) and a pressure of 948 mbar (28.00 inHg).[123] Initially proving resilient to adverse conditions, Norman succumbed to increasing wind shear and lower sea surface temperatures on September 3. Its central dense overcast warmed and its eye filled.[124] At the same time, Norman took a turn to a more westerly direction.[125] On September 4, the hurricane crossed west of 140°W, and warning responsibility shifted to the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC).[126] On the following day, another bout of unexpected intensification ensued and Norman regained major hurricane status.[127]

Current storm information

As of 5:00 a.m. HST (15:00 UTC) September 5, Hurricane Norman is located within 15 nautical miles of 19°30′N 147°42′W / 19.5°N 147.7°W, about 480 miles (775 km) east of Hilo, Hawaii, or about 670 miles (1,080 km) east of Honolulu, Hawaii. Maximum sustained winds are 100 knots (115 mph; 185 km/h), with gusts to 120 knots (140 mph; 220 km/h). The minimum barometric pressure is 962 mbar (hPa; 28.41 inHg), and the system is moving west at 10 knots (12 mph; 28 km/h). Hurricane-force winds extend outward up to 30 miles (45 km), while tropical-storm-force winds extend outward up to 125 miles (205 km) from the center of Norman.

For the latest official information, see:

- The CPHC's latest products on Hurricane Norman

- The CPHC's latest product archive on Hurricane Norman

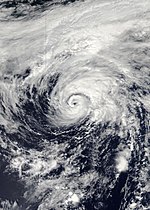

Hurricane Olivia

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

Current storm status Category 3 hurricane (1-min mean) | |||

| |||

| As of: | 8:00 a.m. PDT (15:00 UTC) September 5 | ||

| Location: | 17°06′N 122°18′W / 17.1°N 122.3°W ± 20 nm About 900 mi (1,445 km) SW of Baja California | ||

| Sustained winds: | 105 kt (110 mph; 175 km/h) (1-min mean) gusting to 115 kt (130 mph; 215 km/h) | ||

| Pressure: | 959 mbar (hPa; 28.56 inHg) | ||

| Movement: | W at 11 kt (13 mph; 20 km/h) | ||

| See more detailed information. | |||

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2018) |

Current storm information

As of 8:00 a.m. PDT (15:00 UTC September 5), Hurricane Olivia is located within 20 nautical miles of 17°06′N 122°18′W / 17.1°N 122.3°W, about 900 miles (1,445 km) southwest of the southern tip of Baja California. Maximum sustained winds are 95 knots (110 mph; 175 km/h), with gusts to 115 knots (130 mph; 215 km/h). The minimum barometric pressure is 967 mbar (hPa; 28.56 inHg), and the system is moving west at 11 knots (13 mph; 20 km/h). Hurricane force winds extend outward up to 25 miles (35 km) from the center of Olivia, while tropical storm-force winds extend outward up to 90 miles (150 km).

For the latest official information, see:

- The NHC's latest public advisory on Hurricane Olivia

- The NHC's latest forecast advisory on Hurricane Olivia

- The NHC's latest forecast discussion on Hurricane Olivia

Other system

On August 29, an upper-level low absorbed the remnants of Hurricane Lane to the west-northwest of Hawaii.[128] The storm was assigned the designation 96C by the United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL).[129] Traversing an area with sea surface temperatures 2 °C (3.6 °F) above-normal,[130] the system coalesced into a subtropical storm by August 31.[128] On September 2, the system reached its peak intensity and began to display an eye. Afterward, the system gradually began to weaken, while accelerating northward into colder waters. On September 4, the system was absorbed by a larger extratropical storm in the Bering Sea.[citation needed]

Storm names

The following list of names is being used for named storms that form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean during 2018. Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2019. The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2024 season.[131] This is the same list used in the 2012 season.

|

|

For storms that form in the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility, encompassing the area between 140 degrees west and the International Date Line, all names are used in a series of four rotating lists.[132] The next four names that will be slated for use in 2018 are shown below.

|

|

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms that have formed in the 2018 Pacific hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a tropical wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 2018 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-E | May 10 – 11 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1007 | None | None | None | |||

| Aletta | June 6 – 11 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 943 | None | None | None | |||

| Bud | June 9 – 16 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 948 | Western Mexico, Baja California Sur, Southwestern United States | Unknown | None | |||

| Carlotta | June 14 – 19 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 997 | Southwestern Mexico | Unknown | None | |||

| Daniel | June 24 – 26 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1003 | None | None | None | |||

| Emilia | June 27 – July 1 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 997 | None | None | None | |||

| Fabio | June 30 – July 6 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 964 | None | None | None | |||

| Gilma | July 26 – 29 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1006 | None | None | None | |||

| Nine-E | July 26 – 27 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1008 | None | None | None | |||

| Hector | July 31 – August 13[nb 2] | Category 4 hurricane | 155 (250) | 936 | Hawaii, Johnston Atoll, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands | Minimal | None | |||

| Ileana | August 4 – 7 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 998 | Western Mexico, Baja California Sur | Unknown | 4 | |||

| John | August 5 – 10 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 969 | Western Mexico, Baja California Sur, Southern California | None | None | |||

| Kristy | August 7 – 11 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 991 | None | None | None | |||

| Lane | August 15 – 29 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 922 | Hawaii | > $10.5 million | 1 | |||

| Miriam | August 26 – September 2 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 974 | None | None | None | |||

| Norman | August 28 – Present | Category 4 hurricane | 150 (240) | 937 | None | None | None | |||

| Olivia | September 1 – Present | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 955 | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 17 systems | May 10 – Season ongoing | 160 (260) | 922 | > $10.5 million | 5 | |||||

See also

- 2006 Central Pacific cyclone

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- List of Pacific hurricane seasons

- 2018 Atlantic hurricane season

- 2018 Pacific typhoon season

- 2018 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2017–18, 2018–19

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2017–18, 2018–19

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2017–18, 2018–19

Notes

- ^ The totals represent the sum of the squares for every (sub)tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2018 Pacific hurricane season/ACE calcs.

- ^ Hector did not dissipate on August 13. It crossed the International Date Line, beyond which point it was then referred to as Tropical Storm Hector. It dissipated on August 16.

References

- ^ Dorst Neal. When is hurricane season? (Report). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Background Information: East Pacific Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ^ a b National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 26, 2024). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2023". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Forecasters predict a near- or above-normal 2018 hurricane season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 24, 2018.

- ^ a b Barrios, Verónica Millán. "Temporada de Ciclones 2018". smn.cna.gob.mx.

- ^ Hurricane Specialist Unit (July 1, 2018). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary: June (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Philip Klotzbach on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- ^ Hurricane Specialist Unit (August 1, 2018). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary: July (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ Andrew Latto (May 6, 2018). Tropical Weather Discussion (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (May 7, 2018). Special Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (May 9, 2018). Special Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven II (May 9, 2018). Special Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (May 10, 2018). Tropical Depression One-E Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Robbie Berg (July 12, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression One-E (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Lixion A. Avila (July 31, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Aletta (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ David P. Zelinsky (June 8, 2018). Hurricane Aletta Discussion Number 12 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Robbie Berg (June 5, 2018). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ David Zelinsky (June 9, 2018). "Tropical Depression Three-E Advisory Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ Lixion Avila (June 10, 2018). "Tropical Storm Bud Advisory Number 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (June 10, 2018). Tropical Storm Bud Discussion Number 3 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (June 10, 2018). Hurricane Bud Discussion Number 5 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (June 12, 2018). Hurricane Bud Discussion Number 11 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (June 13, 2018). Tropical Storm Bud Intermediate Advisory Number 15A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (June 14, 2018). Tropical Storm Bud Intermediate Advisory Number 21A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Michael J. Brennan (June 13, 2018). Post-Tropical Cyclone Bud Discussion Number 25 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (June 12, 2018). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (June 14, 2018). Tropical Depression Four-E Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (June 15, 2018). Tropical Storm Carlotta Intermediate Advisory Number 4A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (June 15, 2018). Tropical Storm Carlotta Discussion Number 5 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (June 16, 2018). Tropical Storm Carlotta Discussion Number 10 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (June 17, 2018). Tropical Depression Carlotta Intermediate Advisory Number 12A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (June 18, 2018). Post-Tropical Cyclone Carlotta Discussion Number 18 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ David A. Zelinsky (June 21, 2018). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg (June 21, 2018). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ David A. Zelinsky (June 23, 2018). Tropical Depression Five-E Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 24, 2018). "Tropical Storm Daniel Discussion Number 3". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 24, 2018). "Tropical Storm Daniel Discussion Number 4". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 25, 2018). Tropical Storm Daniel Discussion Number 7 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 25, 2018). "Tropical Depression Daniel Discussion Number 8". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 26, 2018). Tropical Storm Daniel Discussion Number 11 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg (June 27, 2018). "NHC Graphical Tropical Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Stacy R. Stewart (August 21, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Emilia (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 24, 2018). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ David P. Zelinsky (June 24, 2018). "Tropical Depression Seven-E Discussion Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven (July 1, 2018). "Tropical Storm Fabio Discussion Number 3". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ Daniel Brown (July 2, 2018). "Hurricane Fabio Discussion Number 8". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (July 4, 2018). "Hurricane Fabio Discussion Number 14". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Lixion Avila (July 6, 2018). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Fabio Discussion Number 24". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ^ Eric Blake (July 18, 2018). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Lixion Avila (July 26, 2018). "Tropical Depression Eight-E Advisory Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Jack Beven (July 27, 2018). "Tropical Storm Gilma Advisory Number 3". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi; Lixion Avila (July 27, 2018). "Tropical Depression Gilma Advisory Number 5". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (July 29, 2018). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Gilma Discussion Number 13". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ David P. Zelinsky (July 24, 2018). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (July 26, 2018). "Tropical Depression Nine-E Advisory Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ David P. Zelinsky (July 27, 2018). "Tropical Depression Nine-E Discussion Number 2". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (July 27, 2018). "Remnants Of Nine-E Discussion Number 4". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (July 26, 2018). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (July 26, 2018). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (July 31, 2018). "Tropical Depression Ten-E Advisory Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (July 31, 2018). "Tropical Storm Hector Advisory Number 2". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ Robbie Berg; Michael J. Brennan (August 2, 2018). "Hurricane Hector Tropical Cyclone Update". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (August 3, 2018). "Hurricane Hector Advisory Number 9". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ Jack Beven (August 3, 2018). "Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 10". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven (August 4, 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 18 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (August 5, 2018). Hurricane Hector Discussion Number 19 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (July 18, 2018). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Robbie Berg (August 4, 2018). "Tropical Depression Eleven-E Advisory Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ^ Richard Pasch (August 5, 2018). "Tropical Storm Ileana Advisory Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Daniel P. Brown (August 7, 2018). "Remnants of Ileana Discussion Number 12". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ "Van 4 muertos por efectos de la tormenta "Ileana" en Guerrero". El Diaro de Coahuila (in Spanish). August 6, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (July 29, 2018). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (August 2, 2018). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (August 5, 2018). "Tropical Depression Twelve-E Advisory Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Jack Beven (August 6, 2018). "Tropical Storm John Advisory Number 2". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (August 6, 2018). "Hurricane John Advisory Number 5". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Daniel Brown (August 7, 2018). "Hurricane John Discussion Number 9". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Lixion Avila (August 10, 2018). "Post-Tropical Cyclone John Discussion Number 20". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Alex Sosnowski (August 10, 2018). "Dangerous surf from John to affect Southern California beaches into this weekend". State College, Pennsylvania: AccuWeather. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ John L. Beven (August 2, 2018). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Eric Blake (August 7, 2018). "Tropical Depression Thirteen-E Special Forecast/Advisory Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Eric Blake (August 7, 2018). "Tropical Storm Kristy Forecast/Advisory Number 2". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg (August 10, 2018). "Tropical Storm Kristy Forecast/Advisory Number 13". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Lixion Avila (August 11, 2018). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Kristy Forecast/Advisory Number 18". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (August 14, 2018). Tropical Depression Fourteen-E Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (August 15, 2018). Tropical Storm Lane Discussion Number 3 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (August 16, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 9 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (August 18, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 15 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Sam Houston (August 19, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 19 (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Richard Ballard (August 20, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 24 (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Richard Ballard (August 22, 2018). Hurricane Lane Special Advisory Number 30 (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Wendy Osher (22 August 2018). "Lane Intensifies to Dangerous Category 5 Hurricane, 160 mph Winds". Maui Now. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Lane strengthens to Category 5 hurricane, Big Island under hurricane warning". Hawaii News Now. 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Powell (August 22, 2018). "Hurricane Lane Discussion 32". prh.noaa.gov.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Ballard (August 24, 2018). "Tropical Storm Discussion Number 43". prh.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Burke (August 26, 2018). "Tropical Storm Lane Discussion Number 47". prh.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Birchard (August 26, 2018). "Tropical Depression Lane Discussion Number 49". prh.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Birchard (August 27, 2018). "Tropical Storm Lane Discussion Number 53". prh.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Donaldson (August 28, 2018). "Tropical Depression Lane Discussion Number 55". prh.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Donaldson (August 29, 2018). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Lane Discussion Number 59". prh.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ^ Service, US Department of Commerce, NOAA, National Weather. "Central Pacific Hurricane Center - Honolulu, Hawai`i". www.prh.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wroe (August 31, 2018). "Hurricane Miriam Discussion Number 24". prh.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Service, US Department of Commerce, NOAA, National Weather. "Central Pacific Hurricane Center - Honolulu, Hawai`i". www.prh.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stewart, Stacy. NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Stewart, Stacy. NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Avila, Lixion. Tropical Depression Sixteen-E Advisory Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Berg, Robbie. Hurricane Norman Discussion Number 8. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Pasch, Richard. Tropical Storm Norman Advisory Number 3. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Avila, Lixion. Hurricane Norman Advisory Number 6. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Berg, Robbie. Hurricane Norman Advisory Number 8. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Brown, Daniel. Hurricane Norman Special Advisory Number 9. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Brown, Daniel. Hurricane Norman Advisory Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Brown, Daniel. Hurricane Norman Discussion Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Cangialosi, John. Hurricane Norman Discussion Number 12. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Roberts, Dave. Hurricane Norman Discussion Number 14. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Roberts, Dave. Hurricane Norman Discussion Number 15. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Stewart, Stacy. Hurricane Norman Advisory Number 18. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Avila, Lixion. Hurricane Norman Advisory Number 22. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Blake, Eric. Hurricane Norman Discussion Number 26. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Blake, Eric. Hurricane Norman Advisory Number 26. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Cangialosi, John. Hurricane Norman Advisory Number 28. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Houston, Sam. Hurricane Norman Advisory Number 34. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ a b National Weather Service Office in Honolulu, Hawaii [@NWSHonolulu] (August 31, 2018). "Thanks for pointing this out. The circulation that was associated with Lane dissipated several days ago and was absorbed by the same upper level low responsible for this feature. This feature is now a sub-tropical gale low, but we will continue to keep an eye on it!" (Tweet). Retrieved September 2, 2018 – via Twitter.

- ^ "2018 Tropical Bulletin Archive". NOAA. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Bob Henson [@bhensonweather] (September 2, 2018). ""Son of Lane" (if you will) is sitting over a distinct SST anomaly of around 2°C" (Tweet). Retrieved September 2, 2018 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Names". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2013-04-11. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ "Pacific Tropical Cyclone Names 2016-2021". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 12, 2016. Archived from the original (PHP) on December 30, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)