Dreamsnake

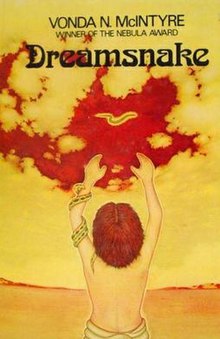

Cover of first edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Vonda N. McIntyre |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin |

Publication date | 1978 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 277 |

| Awards |

|

| ISBN | 0-395-26470-7 |

Dreamsnake is a 1978 science fiction novel by American writer Vonda N. McIntyre. It is an expansion of McIntyre's 1973 novelette "Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand", for which she won her first Nebula Award.[1][2] The story is set on Earth in the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust. The central character, Snake, is a healer who uses genetically modified serpents to cure sickness; one of these is the titular "dreamsnake", an alien serpent whose venom gives dying people pleasant dreams. The novel follows Snake as she seeks to replace her dreamsnake after its death.

The novel was well-received, winning in the 1978 Nebula Award, the 1979 Hugo Award, and the 1979 Locus Poll Award. The strength and self-sufficiency of Snake as a protagonist were noted by several commentators. Reviewers also praised McIntyre's writing and the book's themes. Scholar Diane Wood wrote that Dreamsnake demonstrated "science fiction's potential to produce aesthetic pleasure through experimentation with linguistic and cultural codes",[3] and Ursula K. Le Guin called it "a book like a mountain stream—fast, clean, clear, exciting, beautiful".[4]

The book is considered an example of second-wave feminism in science fiction. McIntyre subverted conventionally gendered narratives by rewriting a typical heroic quest to place a woman at its center, and by using devices such as avoiding gender pronouns to challenge expectations about characters' gender identities. Dreamsnake also explored varying social structures and sexual paradigms from a feminist perspective, and examined themes of healing and cross-cultural interaction.

Background and setting

In 1971, Vonda N. McIntyre, then living in Seattle, set up the Clarion West writers' workshop, which she helped run through 1973. One of the workshop's instructors was Ursula K. Le Guin.[5] During a 1972 workshop session, one of the writing assignments was to create a story from two randomly chosen words, one pastoral, and one related to technology. McIntyre's effort would become her 1973 short story "Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand". That story grew into Dreamsnake, and was used unchanged as the first chapter of the novel.[5] Two other pieces by McIntyre, "The Broken Dome" and "The Serpent's Death", both published in 1978, also constitute sections of the novel,[6] and it is described as a fixup.[7] Dreamsnake, McIntyre's second novel, was released by Houghton Mifflin in 1978, with a cover illustration by Stephen Alexander.[8][9]

The story is set after a nuclear holocaust that "destroyed everyone who knew or cared about the reasons it had happened".[5][10] Most animal species are extinct, regions of the planet are radioactive, and the sky is hidden by dust.[11] Human society is depicted as existing in what journalist Sam Jordison escribes as "low-tech tribalism": the character Arevin, for instance, has never seen a book.[12][13] The exception is the single city of Center, which has sophisticated technology and is in contact with other planets,[5][11][14] but which has a rigidly hierarchical structure and does not permit outsiders to enter.[15] The city also serves as the setting for McIntyre's first novel, The Exile Waiting (1975).[8][9] The protagonist of Dreamsnake is Snake, a healer who uses snake venom in her trade. She travels with three genetically engineered snakes; a rattlesnake, named Sand, a cobra, named Mist, and a "dreamsnake" named Grass, who is described as being from an alien world, and who relieves the pain of dying patients by letting them dream.[10][16]

Synopsis

The novel opens with Snake coming to a nomadic tribe to treat a boy, Stavin, who has a tumor. While her cobra Mist manufactures an antidote in her venom glands, she leaves Grass, the dreamsnake, with Stavin to help him sleep.[17] One of the nomads, Arevin, helps Snake control Mist as the cobra undergoes convulsions through the night, despite the terror that snakes hold for his people. She returns to Stavin in the morning to find that his parents have mortally wounded Grass, afraid he would hurt the boy. Despite her anger, she allows Mist to bite Stavin and inject the antidote. The leader of the nomads apologizes to Snake, and Arevin asks her to stay with them, but Snake explains that she needs a dreamsnake for her work, and must return home and ask for a new one. She expresses fear that the other healers will take her snakes and cast her out instead. As she leaves, Arevin asks her to return someday.[18][a]

Snake stops at an oasis, where she is asked to help Jesse, a woman who has injured herself falling off a horse. Jesse's partner Merideth takes Snake to their camp, leaving Snake's baggage at the oasis. Snake finds that Jesse has broken her spine, leaving her paralyzed, something Snake cannot heal.[19] Merideth and Alex, a third partner, convince Jesse that they should return to Center, where Jesse is from, in the hope that the off-worlders may be able to help her.[20] Wandering around near the camp, Snake sees the body of Jesse's horse, and realizes the area it fell is radioactive; Jesse had lain there long enough to have fatal radiation poisoning. Snake offers to let Mist bite Jesse and relieve her pain; Jesse accepts, and Meredith and Alex bid her farewell. Before she dies, Jesse tells Snake that her family is indebted to Snake, and could help her get another dreamsnake from another planet.[21]

Returning to the oasis, Snake finds that someone has rifled through her belongings, and stolen her journal. Grum, a caravan leader also camped there, says it was the work of a "crazy".[22] Back among the nomads, Arevin decides to go after Snake.[23] Snake crosses the Western desert to the town of Mountainside, where the mayor's son Gabriel asks her to heal the mayor.[24] While staying with them, Snake invites Gabriel to sleep with her, and learns that he impregnated a friend as a result of being improperly taught "biocontrol", and that this led to a difficult relationship with his father.[25] She tells him he can still learn, and suggests he find a different teacher when he leaves Mountainside, as he intends to do.[25]

While checking on her horses, Snake meets Melissa, a girl with a severely burned face who helps the stablemaster, who takes credit for her work.[26] Her scars make her self-conscious of her appearance in a town of otherwise beautiful people.[27] Shortly after, Snake is attacked on her way to the mayor's house by a man she assumes is the crazy.[28] She discovers that Melissa has been physically and sexually abused by the stablemaster, and uses this knowledge to convince the mayor to free her. Melissa accompanies Snake as her adopted daughter when Snake leaves for Center.[27] Snake explains to her that dreamsnakes are very rare, and that the healers have not found a way to make them breed.[29] Meanwhile, Arevin arrives at the healer's dwelling north of Mountainside, but is told that Snake isn't there, and goes south to find her.[30] In Mountainside he is briefly detained on suspicion of having been Snake's attacker, but is released.[31]

Snake and Melissa cross the eastern desert and reach Center, but are turned away, like every previous emissary from the healers.[32] Soon after they return to the mountains, they are attacked again by the crazy, who demands the dreamsnake, and collapses when he learns the serpent is dead. Snake learns he is addicted to dreamsnake venom.[33] Snake makes him take her to a community whose leader, North, possesses several dreamsnakes, and occasionally allows his followers to be bitten by them as a reward.[34] The community lives in a "broken dome", a relic of a past civilization.[35] North, who bears all healers a grudge, puts Snake in a large, cold pit filled with dreamsnakes.[36] In the pit, Snake realizes that the intense cold brings dreamsnakes to maturity, and they breed in triplets, rather than the paired sexes of Earth.[37] Her immunity to venom allows her to survive the pit, and eventually to climb out. While North's henchmen are in venom-induced comas, she finds Melissa similarly comatose, and escapes with her and a bag of dreamsnakes. She is met outside by Arevin, who helps Melissa recover.[38]

Themes and structure

Dreamsnake is considered an exemplar of second-wave feminism in science fiction, which had largely been devoted to masculine adventures prior to a body of science fiction writing by women in the 1960s and 1970s that subverted conventional narratives.[39][40] McIntyre uses the post-apocalyptic setting to explore a variety of social structures and sexual paradigms from a feminist perspective.[15] By giving female desire a prominent place in the narrative, she explores gender relations in the communities Snake visits.[41] As in McIntyre's later Starfarers books, women are depicted in many leadership positions.[42] The archetype of a heroic quest is rewritten: the central figure in Dreamsnake is a woman,[43] and the challenges she faces require healing and care, rather than force, to overcome.[44] A conventional fictional pattern of a hero being pursued, or waited for, by a female lover, is reversed, as Arevin follows Snake, who receives his support but does not require rescue.[45] Gender expectations are also subverted through the character of Merideth, whose gender is never disclosed,[46] as McIntyre entirely avoids using gender pronouns,[47] thereby creating a "feminist construct" that suggests a person's character and abilities are more important than their gender.[46] Characters are often introduced with reference to their profession, and later casually revealed to be female, thereby potentially subverting readers' expectations.[44][48][49]

The book's feminist themes are also related to an exploration of healing and wholeness, according to scholar Inge-Lise Paulsen. Snake is a professional healer, ostensibly fitting the stereotype of a woman in a nurturing role, but McIntyre depicts her as someone who is a healer because she was trained to be, and because it was an ethical choice, and not as a consequence of her femininity. Although she finds a family in Arevin and Melissa, that is not where Snake seeks her "ultimate fulfillment as a woman":[50] her triumph at the story's end comes from her discovery of the dreamsnakes' breeding habits. Love is depicted as insufficient for a relationship; Arevin must learn to trust Snake's strength, and resist the temptation to protect her. The ideal of mutual respect is also shown in the utopian structure of the nomads' society.[50] The nomads respect individual agency, in contrast to the people of the city, who isolate themselves from the world from a desire to protect themselves.[51] Paulsen sees this as a cultural tendency typical of patriarchy, and writes that McIntyre's depiction of an ethical need for wholeness and an understanding of connections between the facets of society is also found in the work of Le Guin and in Doris Lessing's Canopus in Argos series.[52]

In Dreamsnake McIntyre uses language conveying complex and multiple meanings, thus challenging readers to engage deeply.[3] Snake's name, and the snakes she uses, invoke images drawn from religion and mythology. For instance, modern-day physicians use a caduceus, or staff with intertwining snakes, as an emblem: in Greek mythology, the caduceus is the symbol of Hermes, and signifies that its carrier is a bearer of divine knowledge.[53] Snakes have other symbolic meanings, including both death and rejuvenation. They are a recurring motif in fiction, being depicted in widely varying roles and forms.[54][55] Their symbolic association with both poison and healing, for instance, connects McIntyre's protagonist to Asclepius, the Roman god of healing, who carries a serpent-entwined rod.[54] These dual meanings are illustrated by the dreamsnake Grass, who in the story is a powerful tool for the healer while also being an object of fear for the desert people.[56] Snake's use of serpents plays on the biblical myth of Genesis, reversing it so the woman controls the snakes.[57] The depiction of Center, a place of sophisticated technology that has cut itself off from the rest of society, is associated with an exploration of the relationship between "centre and margins, insider and outsider, self and other" that is also found in McIntyre's The Exile Waiting and Superluminal (1983).[58] Center exhibits a rigid social order; in contrast, social change occurs outside, at the margins of society, and Center, despite its name, is rendered irrelevant.[59]

Dreamsnake, along with much of McIntyre's work, also explores the effects of freedom and imprisonment. Many of her characters attempt to free themselves from shackles of varying kinds, including self-imposed psychological limitations, the challenges created by physical infirmity or appearance, and oppression by other humans.[60] Snake encounters two freed slaves who work for the mayor of Mountainside, who freed them by banning slavery in his town. One bears a ring in her heel as a relic of enslavement; when Snake tells her she could have it removed, she is overjoyed, though the process risks laming her. The other is notionally free, but feels obliged to serve the mayor's every whim out of gratitude.[61] Melissa is handicapped differently: because of her disfiguring burns, in a society that judges people on their physical appearance, she leads a hidden existence.[62] Other characters who are fettered in some way include North, whose incurable gigantism has led to constant psychotic rage; the "crazy", trapped by his addiction; Gabriel, embarrassed by his failure at controlling his fertility; and Arevin, who feels caught by familial responsibility.[63]

Interactions between cultural codes are also a recurring theme in Dreamsnake, sometimes also featuring dual meanings, as when Snake and Arevin discuss the term "friend", to which Arevin attaches greater significance, or in the figurative offer of help that the mountain people use to offer a sexual relationship.[64] Arevin's initial unwillingness to share his name with Snake, and his explanation of what "friend" signifies to him shows his people's deep-rooted suspicion of strangers; and when he leaves, he seeks to explain to the healers the cultural factors that resulted in Grass being killed.[64] Cultural biases also impede the healers' ability to understand the biology of the dreamsnakes. Their knowledge of Earth biology leads them to erroneously assume creatures mate in pairs; only Snake's circumstances enable her to discover they are triploid.[65] The narrative thus argues that acceptance of difference can lead to growth and change.[66]

Characterization

Multiple reviewers highlighted Dreamsnake's strong female protagonist.[67][68] Snake's centrality to the book allows McIntyre to explore gender as its central theme.[57] McIntyre uses her character to subvert gendered tropes:[50][57] Snake, like many of McIntyre's protagonists, is an assertive woman in a traditionally male role, although she is a healer, rather than an archetypal male hero.[69][48] Most of the male characters in Dreamsnake are depicted in a negative light, as with the mayor of Mountainside, the abusive stablemaster, or North; Arevin, who is "gentle and persistent", is in the background for most of the book.[49]

Orson Scott Card described Snake's character as self-sufficient: she has solved her own problems and subverted the expectation that she would be rescued at the novel's end. For Card, Snake has much in common with the Lone Ranger, improving peoples' lives with "love and understanding": she immunizes Grum's people, rescues Melissa, and helps Gabriel overcome his inability to control his fertility, a "hideous problem" in their society.[70] Scholar Sarah LeFanu describes Snake as an "older and wiser" version of Mischa, the protagonist of The Exile Waiting, who struggles through much adversity before escaping the city of Center. Snake is depicted as "brave, loyal and intelligent", with a strong desire for justice, and a kind nature.[71]

Scholar Carolyn Wendell writes that Snake is more able to make her own choices than many of the other characters in Dreamsnake. Her freedom gives her greater responsibility, and allows her to free others, such as Gabriel and Melissa.[72] While exploring her sexuality, Snake also retains more agency than is typical for female characters in the genre.[48] According to Lefanu, through Snake's sexual activity, and the sexual politics of the book more generally, McIntyre suggest that in the world of Dreamsnake, it is "possible both to be a woman and to be fully human".[71] Snake's character has been described as an example of feminist reclamation of the archetype of a witch: a person shunned by patriarchal society, redrawn as an image of female power.[73]

Reception and recognition

Dreamsnake won multiple awards, including the 1978 Nebula Award for Best Novel,[74][16] the 1979 Hugo Award for Best Novel[16][75] and the 1979 Locus Poll Award for Best Novel.[16][76] It also won the Pacific Northwest Booksellers' Award,[77] and was nominated for the 1979 Ditmar Award in International Fiction.[78] In 1995, Dreamsnake was put on the shortlist for the Retrospective James Tiptree Award.[79] "Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand" had won McIntyre her first Nebula Award, for best novelette, in 1974,[1][2] as well as being nominated for the Hugo Award in the same category,[80] and the Locus Award for Best Short Fiction.[81] In 1980 the paperback was nominated for the American Book Awards.[82][b] Dreamsnake has been identified as part of a wave of feminist speculative fiction that emerged in the 1970s and established the position of female authors in a field where they had been marginalized. This body of work included writing by Le Guin, Kate Wilhelm, and James Tiptree Jr..[83]

McIntyre's writing was highlighted by several reviewers. The Santa Cruz Sentinel described the book as a "truly mesmerizing story",[67] while Sally Estes of the American Library Association called it "gripping",[68] and the Cincinnati Enquirer described it as among the year's "most sensitively-written and poetic novels".[84] Le Guin praised Dreamsnake, describing it as "a book like a mountain stream—fast, clean, clear, exciting, beautiful".[4] Writing in 2011, she elaborated: "Dreamsnake is written in a clear, quick-moving prose, with brief, lyrically intense landscape passages that take the reader straight into its half-familiar, half-strange desert world, and fine descriptions of the characters' emotional states and moods and changes."[47] In 1981 science fiction scholar Marshall Tymn commented that it was the "poetically negotiable authenticity" of Snake's adventure that made the book successful, and that it was an enduring work among those that had won Hugo and Nebula awards.[85] A 2012 review in The Guardian called it a "challenging, unsettling book", and said that McIntyre's fictional world was "expertly drawn".[12]

The themes, symbology, and use of language explored in Dreamsnake also attracted comment. Scholar Diane Wood wrote that the novel showed "science fiction's potential to produce aesthetic pleasure through experimentation with linguistic and cultural codes".[3] Wood also praised McIntyre's theme of communication across cultures, saying that her style and "vivid characterization" strengthened her message of "greater compassion and understanding", and made the "richly textured novel" a pleasure to read.[86] Scholar Gary Wesfahl favorably compared McIntyre's depiction of snakes to that in other works of speculative fiction, describing Dreamsnake as the "high-point" in portrayals of fictional relationships between snakes and humans.[55] Card also highlighted the self-sufficiency of Snake's character, and added that McIntyre had successfully tied together a "superficially episodic story", and had created a "vicious but beautiful world", with well drawn characters.[70]

Some reviewers commented on the length and structure of the novel, and made varyingly favorable comparisons to "Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand". A review for the Charlotte Observer was critical of Dreamsnake, saying that nothing substantial occurred for much of the book, and that it was an example of why even excellent short stories ought not to be expanded into novels,[87] while Estes also commented that it had "lost some of the subtlety" of the original short story.[68] Other reviewers commented negatively on Arevin's brief appearances in the story, as being unnecessary. Wendell wrote in 1982 that the device was a reversal of a usual fictional trope, and that these reviewers may have been uncomfortable with a female protagonist solving her difficulties on her own.[45] Brian Stableford commented that Dreamsnake had "little in the way of a plot", but that the story didn't rely on its plot for its effectiveness; he described it instead as a "novel of experience", written with a "good deal of thought and sincerity", and very readable.[88] Card wrote that he was initially hesitant about the expansion of "Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand", which he called a "gem perfectly polished". He was also critical of some passages, writing that some, such as the characterization of Melissa, were maudlin, while others dragged on too long, but that ultimately, he did not wish for the book to end.[70]

Notes and references

- ^ "Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand" ends with Snake's departure from the nomads' camp.[18]

- ^ The American Book Awards distinguished between hardcover and paperback editions; Dreamsnake was thus eligible for the 1980 award because its first paperback edition had been released in 1979, while the 1978 version had been published as a hardcover.[82]

- ^ a b Ashley 2007, pp. 23–26.

- ^ a b "Nebula Awards 1974". Science Fiction Awards Database. Locus. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c Wood 1990, p. 63.

- ^ a b "Dreamsnake". The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. 54 (4–6): 31. 1978. Republication of Le Guin's comment in the book's blurb.

- ^ a b c d Holland, Steve (April 4, 2019). "Vonda N McIntyre obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Stephenson-Payne, Phil. "Stories, Listed by Author". Index to Science Fiction Anthologies and Collections. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ Langford, David; Nicholls, Peter; Morgan, Cheryl (September 20, 2020). "Hugo". In Nicholls, Peter; Clute, John; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Clute, John (April 13, 2020). "McIntyre, Vonda N.". In Nicholls, Peter; Clute, John; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Lefanu 1989, p. 90.

- ^ a b Sandomir, Richard (April 5, 2019). "Vonda N. McIntyre, 70, Champion of Women in Science Fiction, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Paulsen 1984, p. 104.

- ^ a b Jordison, Sam (April 16, 2012). "Back to the Hugos: Dreamsnake by Vonda N McIntyre". The Guardian. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Cordle 2017, p. 177.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Wolmark 1988, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d Lacey 2018, pp. 375–376.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 1–7.

- ^ a b McIntyre 1978, pp. 7–22.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 23–30.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 33–38.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 45–54.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 64–69.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 60–62.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 84–88.

- ^ a b McIntyre 1978, pp. 111–116.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 104–107, 134–135.

- ^ a b McIntyre 1978, pp. 142–143, 149–157.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 126–130.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 158–159.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 164–171.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 216–218.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 179–185.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 199–201.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 205–207.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 220–225.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 234–237.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 254–255.

- ^ McIntyre 1978, pp. 267–275.

- ^ Kilgore 2000, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Wolmark 1988, p. 51.

- ^ Wolmark 1994, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Kilgore 2000, p. 266.

- ^ Wolmark 1994, p. 65.

- ^ a b Williams 2002, pp. 152–154.

- ^ a b Wendell 1982, p. 143.

- ^ a b Kilgore 2000, p. 275.

- ^ a b Le Guin 2016, pp. 139–142.

- ^ a b c Cordle 2017, pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b Wendell 1982, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Paulsen 1984, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Paulsen 1984, pp. 104–106.

- ^ Paulsen 1984, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Jones 1983, pp. 277–279.

- ^ a b Wood 1990, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Westfahl 2005, p. 370.

- ^ Wood 1990, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c Wolmark 1994, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Wolmark 1994, p. 57.

- ^ Wolmark 1994, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Wendell 1982, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Wendell 1982, pp. 127–129.

- ^ Wendell 1982, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Wendell 1982, pp. 141–143.

- ^ a b Wood 1990, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Wood 1990, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Wolmark 1994, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b "Dreamsnake, by Vonda McIntyre". Santa Cruz Sentinel. July 22, 1979. p. 23.

- ^ a b c Estes, Sally (September 17, 1978). "Fear the Dragon No Longer". The Park City Daily News. p. 34.

- ^ Wendell 1982, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b c Card, Orson Scott (November 10, 1978). "Dreamsnake". Science Fiction Review. 7 (4): 32–33.

- ^ a b Lefanu 1989, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Wendell 1982, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Bammer 2012, pp. 85–86.

- ^ "Keith Stokes, Vonda N. McIntyre honored with SFWA Service Award". SWFA. March 11, 2010. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "1979 Hugo Awards". The Hugo Awards. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "1979 Locus Awards". Locus Magazine. 1979. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Strahan 2016, p. 349.

- ^ "1979 Ditmar Awards". Locus Magazine. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "1995 Retrospective Honor List". James Tiptree, Jr. Award. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ "1974 Hugo Awards". World Science Fiction Society. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ "1974 Locus Awards". Locus Magazine. Archived from the original on October 1, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Tymn 1981, pp. 201–203.

- ^ Lavigne 2013, pp. 24–28.

- ^ Waite, Dennis (August 6, 1978). "Talking of Time Warps". The Cincinnati Enquirer. p. 119.

- ^ Tymn 1981, p. 372.

- ^ Wood 1990, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Lloyd, David (June 2, 1978). "Another Best Seller?". The Charlotte Observer. p. 52.

- ^ Stableford, Brian (May 1975). "Dreamsnake". Foundation (16): 70–71.

Sources

- Ashley, Mike (2007). Gateways to Forever: The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1970 to 1980. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-003-4.

- Bammer, Angelika (2012). Partial Visions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-98010-9.

- Cordle, Daniel (2017). Late Cold War Literature and Culture: The Nuclear 1980s. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-137-51308-3.

- Strahan, Jonathan, ed. (2016). "Little Sisters – Vonda N. McIntyre". The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year, Volume Ten. Solaris. ISBN 978-1-84997-932-0.

- Jones, Anne Hudson (Winter 1983). "The Healer-Patient/Family Relationship in Vonda N. McIntyre's "Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand"". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 26 (2): 274–280. doi:10.1353/pbm.1983.0037. PMID 6844117.

- Kilgore, De Witt Douglas (July 2000). "Vonda N. McIntyre's Parodic Astrofuturism". Science Fiction Studies. 27 (2): 256–277. JSTOR 4240879.

- Lacey, Lauren J. (2018). "Science Fiction, Gender, and Sexuality in the New Wave". In Canavan, Gerry; Link, Eric Carl (eds.). The Cambridge History of Science Fiction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 367–379. ISBN 978-1-316-73301-1.

- Lavigne, Carlen (2013). Cyberpunk Women, Feminism and Science Fiction: A Critical Study. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-0178-6.

- Lefanu, Sarah (1989). Feminism and Science Fiction. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33287-5.

- Le Guin, Ursula (2016). "The Wild Winds of Possibility: Vonda N. McIntyre's Dreamsnake". Words Are My Matter. Small Beer Press. ISBN 978-1-61873-134-0.

- McIntyre, Vonda N. (1978). Dreamsnake. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-26470-6.

- Paulsen, Inge-Lise (1984). "Can Women Fly?: Vonda McIntyre's Dreamsnake and Sally Gearhart's The Wanderground". Women's Studies International Forum. 7 (2): 103–110. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(84)90064-5.

- Tymn, Marshall B. (1981). The Science fiction reference book. Starmont House. ISBN 978-0-916732-49-3.

- Wendell, Carolyn (1982). "Responsible Rebellion in Vonda McIntyre's Fireflood, Dreamsnake, and Exile Waiting". In Staicar, Tom (ed.). Critical encounters II : Writers and Themes in Science Fiction. F. Ungar. pp. 125–144. ISBN 978-0-8044-2837-8.

- Westfahl, Gary (2005). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32952-4.

- Williams, Donna Glee (2002). "Dreamsnake". In Kelleghan, Fiona (ed.). Classics of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature. Salem Press. ISBN 978-1-58765-050-5.

- Wolmark, Jenny (1988). "Alternative futures? Science fiction and feminism". Cultural Studies. 2 (1): 48–56. doi:10.1080/09502388800490021. ISSN 0950-2386.

- Wolmark, Jenny (1994). Aliens and Others: Science Fiction, Feminism and Postmodernism. University of Iowa Press. ISBN 978-0-87745-447-2.

- Wood, Diane S. (1990). "Breaking the Code: Vonda N. McIntyre's Dreamsnake". Extrapolation. 31 (1): 63–72. doi:10.3828/extr.1990.31.1.63. ISSN 0014-5483.

External links

- Dreamsnake title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database