Staffordshire Bull Terrier

| Staffordshire Bull Terrier | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:GLIMMER MAN Domidar Dogs.jpg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common nicknames | Stafford,[1] Staffy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin | United Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Foundation stock | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dog (domestic dog) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

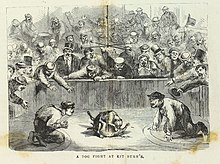

The Staffordshire Bull Terrier, commonly called the Staffy or Stafford, is a shorthaired, purebred dog breed of medium size that originated in the Black Country of Staffordshire in the English Midlands.[2] It is designated in the terrier group, one of several group designations used by various breed registries.[3][4] It has been generally agreed by authorities that the Stafford's earliest beginnings trace back centuries to mastiff types when the old bulldogs were closely linked, and used for bull and bear baiting which required large dogs in the 100–120 lb range.[5] After Parliament passed the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835, dog fighting became a clandestine sport. Breeders migrated away from the heavier bulldogs, and introduced terrier blood into their crosses for gameness and agility.[6] These ancestral crosses of bulldogs and terriers produced the first "bull and terriers".[7] In the grand scheme of canine history, the story behind the modern Staffordshire Bull Terrier is rather brief and somewhat confusing due to the multiple aliases that were hung on these dogs in centuries past, such as the Patched Fighting Terrier, Staffordshire Pit-dog, Brindle Bull, and Bull-and-Terrier.[7] Similar crosses were also called half-and-halfs and half-breds but were more commonly known as the bull and terrier, which was not a breed but the progenator of several breeds.[6]

Individual types and styles of dogs that were crossed varied by geographic region.[8] For example, the progeny from one area may have a higher percentage of terrier than bulldog, whereas other reports claim that bulldog to terrier was preferred over bull and terrier to bull terrier.[8] Dog breeders made careful selections in their breeding programs in order to produce inheritable traits from specific dog types. Many of the breed types that were used to create the early fighting dogs have long since become extinct, but certain genetic traits are represented in the new breeds that were developed over time.[9]

By the mid-1860s, James Hinks was developing a new breed which came to be known as the 'Bull Terrier'.[6][a] Hinks' son, also named James, described the new breed as "the old fighting dog civilized, with all of his rough edges smoothed down without being softened; alert, active, plucky, muscular, and a real gentleman”.[6] Another group of breeders preferred the fighting bulldog–terrier crosses over the Hinks’ outcrosses, and two different breeds of Bull Terriers emerged: the Hink's Bull Terrier or White Cavalier, and the Staffordshire Bull Terrier.[6][10] An article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) states that the early history of the Staffordshire Bull Terrier "is identical to the Bull Terrier which was a cross between a Bulldog and a Black and Tan Terrier".[11] It describes the breed as the result of deliberately crossing "a Bull Terrier (itself a mix of a Bulldog and a Black and Tan Terrier) and a smaller terrier (possibly a Manchester Terrier or a White Terrier)."

It was sometime during 1932 and 1933 that dog breeder Joe Dunn from Quarry Bank worked toward getting the Black Country breeders' strain of bull terriers recognised as purebreds by The Kennel Club.[12] In early 1935, Dunn obtained permission from TKC to hold a variety dog show to gage the level of interest in showing Staffords, and offered cash to attract owners. The show was held in April 1935, and was a success. After the show, Dunn decided to form a club, and invited other dog breeders to the meeting.[12] Those in attendance agreed to name their club "The Staffordshire Bull Terrier Club". It was subsequently accepted by The Kennel Club (TKC) in July 1935, marking an official milestone for the Staffordshire Bull Terrier's acceptance into TKC's breed registry.[12] It wasn't until 1974 that the American Kennel Club (AKC) admitted the Staffordshire Bull Terrier as their 121st registered breed.[13][14] how the duck can it be a Staffordshire bull bif it's not from Stafford there's no Stafford in America

Ancestral origins

The unregulated breeding of the Staffordshire Bull Terrier has led to misconceptions surrounding its origins and thereafter because its exact genetic makeup can be inconsistent.[15]: 8 At the time, traceable pedigrees did not exist. It has been generally accepted that the breed descended from the 19th-century bulldog–terrier crosses that were bred for dogfighting.[15]: 8 Joanna de Klerk, DVM, author of The Complete Guide to Staffordshire Bull Terriers surmised that after selective breeding refined the bull and terrier cross into the English Bull Terrier, the Stafford eventually emerged from the original bull and terrier, and only after a breed standard was created by more regulated breeding did it gain recognition by The Kennel Club in 1935.[15]: 8

The article, Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences states: "Modern breeding practices, focused on distinct breeds with strict aesthetic requirements and closed bloodlines, only emerged in the 19th century, and claims for the antiquity (and long-term continuity) of modern breeds are based upon little or no historical or empirical evidence. In fact, recent historical records clearly demonstrate that most modern breeds experienced significant population fluctuations within the past 100 y (Table S1). Here, we only use the term “breed” when referring to modern dog breeds recognised by kennel clubs."[11] Table S1 describes the early history of the Staffordshire Bull Terrier as "...identical to the Bull Terrier which was a cross between a Bulldog and a Black and Tan Terrier. This breed is the result of a deliberate cross between a Bull Terrier (itself a mix of a Bulldog and a Black and Tan Terrier) and a smaller terrier (possibly a Manchester Terrier or a White Terrier)."[11]

History

The progeny of the hybrid crosses between bulldogs and terriers were sometimes referred to as half-and-halfs and half-breds but became more commonly known as the bull and terrier.[6] Of the six distinct breeds that descended from the bull and terrier breeds, five are recognised by the American Kennel Club (AKC) in the following order: Bull Terrier, Boston Terrier, American Staffordshire Terrier (AmStaff), Staffordshire Bull Terrier, and Miniature Bull Terrier.[8]: 39 The same five breeds are also recognised by the Canadian Kennel Club (CKC), and Fédération cynologique internationale (FCI). The American Pit Bull Terrier (APBT) is recognised by the United Kennel Club (UKC). The English Kennel Club recognizes only four of the breeds and does not accept the AmStaff or APBT.[8]: 39 The United Kennel Club describes the Bull Terrier as "the direct descendant of the original bull-and-terrier cross made in England, specifically to bait bulls and, later to fight in pits".[16] Their description of the Staffordshire Bull Terrier states that the breed shares "the same ancestry as the Bull Terrier, i.e. Bulldog crossed with the Black and Tan terrier, and was developed as a fighting dog."[14][17]

Same origins as Bull Terrier

In the mid–19th century, the bull and terrier hybrids were known by several different aliases, such as the Patched Fighting Terrier, Staffordshire Pit-dog, Brindle Bull, and Bull-and-Terrier.[7]A common name was simply the Bull Terrier, which was later associated with the Hinks' Bull Terrier;[15]: 18 a socially acceptable "gentleman's companion" with refinement, cleaner lines, and courage without aggressive tendencies.[18] During the development of Hinks' new breed of Bull Terrier, also known as the White Cavalier, various undocumented outcrosses were used that the devotees of the original strains of bull and terrier crosses didn't like, such as the Dalmatian and Collie, and they chose instead to remain loyal to their preferred type.[19][20] As a result, two different breeds of Bull Terriers emerged: the Bull Terrier and Staffordshire Bull Terrier.[6][21] The Bull Terrier's fighting heritage was left behind whereas breeders of Staffordshire Bull Terriers in the UK continued their illegal competitions which paralleled what was happening in the U.S. with the American Staffordshire Terrier; neither breed could gain official acceptance in their respective native lands. "No established registry wanted to be affiliated with a dog that drew the blood of its own kind for a living."[21]

By 1874, in Britain the first Kennel Club Stud Book was published, which included Bull Terriers[22] and Bulldogs.[23] In 1935, The Kennel Club accepted Staffordshire Bull Terriers into their studbook with established breed standards.[2] It wasn't until 1974 that the AKC admitted Staffordshire Bull Terriers as a purebred as their 121st registered breed.[13]

Theories of origin

Some will argue that, despite undocumented origins, the Stafford originates solely from the original Old English Bulldog with no crossbreeding to terriers.[15]: 10 According to The Staffordshire Bull Terrier Club of America, the Manchester Terrier as well as the now-extinct English White Terrier were used in the bull and terrier crosses, as were varieties of the old working terriers.[10] While the Stafford was considered the other bull and terrier, it was not as readily accepted into the breed registries of either the KC or AKC because of their fighting ancestry. In 1935, "fanciers of the working class dog" met in England and formed the parent club for the Staffordshire Bull Terrier to create the breed standard.[10] The first Staffordshire Bull Terrier show was held in August 1935 at Cradley Heath in West Midlands. There were 60 dogs and bitches entered in the show.[7]

In the Spring 2013 issue of The Stafford Knot, Jason Nicolai describes some important evolutionary factors in the breed standards of the Staffordfordshire Bull Terrier, and that it is "very often misquoted and misunderstood."[24] The standard for the modern Stafford aligns with the breed's transformation from its bull and terrier ancestry as a fighting dog to a modern conformation show dog.[24] Some book authors have compared 19th-century drawings or paintings to depict similarities in visual appearances of the modern Staffords. Author and Stafford enthusiast, James Beaufoy, wrote that there is "interesting evidence" in some of the early 19th-century paintings that depict conformation and coat color similarities of modern Staffords when compared to the Old English Bulldog. One such painting is by artist Abraham Cooper (1817), titled Crib and Rosa.[25]

The late A.W.A Cairns, former editor of the online Stafford Magazine published by Southern Counties Staffordshire Bull Terrier Society,[26][27] wrote, "Kennel Club recognition of the breed is shrouded in mystery. Recognition was announced in the April 1935 Kennel Gazette in the name of Staffordshire Bull Terrier. There was no explanation as to how this came about. No Breed Club or Breed Standard existed."[28]

To some extent, Cairns aligns with Beaufoy "in the context of Kennel Club recognition the Staffordshire Bull Terrier is a relatively 'new breed'".[28] Cairns believed a "Stafford-like animal existed at the turn of the 19th Century" and admitted, with the "possibility for slight prejudice", that "the only modern dog of this type is the Staffordshire Bull Terrier". However, Cairns further clarified that the pedigree inscribed on the plaque of the Crib and Rosa painting, specifically the words "the famous Staffordshire bitch", is not suggesting that it was a Staffordshire Bull Terrier, but that "it could be concluded that animals of that type, existed in that county before 1816."[28] Had that theory been proven true, then the modern Staffordshire Bull Terrier would be considered a descendant of purebred bulldogs with no crossbreeding to terriers.[25]

DNA analysis

In 2017, a genome-wide study suggested that all of the bull and terrier–type dogs, including the Staffordshire Bull Terrier and five other distinct breeds, map back to the terriers of Ireland and to origins which date to the period 1860–1870. The timing corresponds with historical descriptions of dog fighting competitions in Ireland, a lack of accurate stud book documentation, and, as a result, undocumented dog crosses at the time when these breeds were first created.[29][30][31]

DNA studies have brought some clarity to the hybridization mystery of bull and terrier hybrids, suggestive of a New World dog within some modern breeds. The study states that "all of the bull and terrier crosses map to the terriers of Ireland and date to 1860-1870."[29] The historical descriptions confirm the popularity of such crosses in Ireland, but they do not positively identify all the breeds that were involved.[29] As supported by the DNA study, as well as the AKC and KC, references to the historic bull and terrier were not as a bona fide breed;[6][8] rather, the term was used to describe a heterogeneous group of dogs that may include purebreds of different breeds, or crosses of those breeds. Bull and terrier hybrids, or pit bull types are considered the forerunner of several modern standardised breeds.[32]

Early protection

The Cruelty to Animals Act 1835 made blood sports illegal, and effectively stopped bull- and bear-baiting in the UK.[25][33] Baiting required large arenas which made it easier for authorities to police, whereas illegal dog fighting was much harder to terminate because fight sponsors kept their venues hidden and closely guarded in private basements and similar locations. As a result, dog fighting continued long after bull- and bear-baiting had ceased. It was not until the passage of the Protection of Animals Act 1911 that organised dog fighting in Britain largely came to an end.[25]

The Kennel Club

"The early proto-staffords provided the ancestral foundation stock for the Staffordshire Bull Terrier, the American Pit Bull Terrier and the American Staffordshire Terrier.[19][34] In 1930, the name "Staffordshire Bull Terrier" first appeared in advertisements for dogs of the type.[25] Throughout 1932 and 1933, attempts to achieve Kennel Club recognition for the breed were made by dog-show judge and breeder, Joseph Dunn, but the Stafford's early origins as a fighting dog made it difficult to gain acceptance.[12][19][34] In early 1935, Dunn obtained permission from TKC to hold a variety dog show to see if it would attract Stafford owners to show their dogs; he offered cash as a special attraction. The show was held in April 1935 and was a success.

In May 1935, the KC approved the name "Staffordshire Bull Terrier"; the first name requested, "Original Bull Terrier", had been rejected.[19][25] Dunn decided to form a club and invited other dog breeders to participate.[12] In June 1935, the Staffordshire Bull Terrier Club was formed during a meeting at the Old Cross Guns pub in Cradley Heath; a breed standard was approved the same day, and further shows were held that year.[25] Other pivotal breeders involved in acquiring breed recognition were Joe Mallen and actor Tom Walls.[25] The first champions recognised in England were the bitch Lady Eve and the stud Gentleman Jim in 1939.[7][35]

Phil Drabble reported that among the various types of bull and terrier, the type from Cradley Heath was recognised as a separate breed to be named the Staffordshire Bull Terrier.[36] It was subsequently accepted by The Kennel Club (TKC) in July 1935, marking an official milestone for the Staffordshire Bull Terrier's acceptance into TKC's breed registry.[12]

The breed was fully accepted by the Fédération Cynologique Internationale in 1954.[37]

American Kennel Club

The Staffordshire Bull Terrier is among the breeds in the AKC Terrier group, as are the Bull Terrier and American Staffordshire Terrier, all with a similar history and classified as "bull types".[14] The Staffordshire Terriers had arrived in America by the mid-1800s. After their arrival, some American breeders developed a taller, heavier offshoot.[38] According to the AKC, "From among the profusion of breeds created in this way, most now extinct, the Staffordshire Bull Terrier, perfected by one James Hinks, of Birmingham, England, in the mid-19th century, emerged as one of the most successful and enduring. The breed name that finally came to these burly, broad-skulled terriers is a nod to the county of Staffordshire, where the breed was especially popular."[14] Over time, the two types were recognised by the AKC as separate breeds: the Staffordshire Bull Terrier and the American Staffordshire Terrier.[38][39]

In an effort to achieve AKC recognition of the Stafford, Steve Stone organised the US Staffordshire Bull Terrier Club, 14 January 1967.[40] There were few Staffords in the country at that time, most being imports from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and other parts of the world. The first attempts to encourage club membership and gain AKC recognition began with a rally held in the summer of 1967 which resulted in 14 memberships and 8 Staffords registered by the club. By year's end, the count had increased to 39 registered dogs. Dog imports continued, and the number of memberships and registered dogs increased but it would take nearly a decade of hosting sanctioned shows and demonstrating consistency in the breed standard by maintaining responsible breeding practices that the club would acquire official AKC recognition.[14][40]

Initially, the AKC refused to recognise any breeds that were associated with dogfighting, but in 1936 they recognised the Staffordshire Terrier, later changing the breed's name to the American Staffordshire Terrier.[39][38] In 1974, the AKC officially recognised the Staffordshire Bull Terrier Club, giving it recognition as the official AKC Parent Club representing the Staffordshire Bull Terrier. On October 1, 1974, the AKC accepted the first Staffordshire Bull Terrier to be registered in the AKC Stud Book, English import, Ch. Tinkinswood Imperial. The Australian import, Northwark Becky Sharpe, was the first U.S. champion.[10][40]

Characteristics

The Stafford is a stocky, muscular and unusually strong dog of small to medium size. It usually stands 36–41 cm at the withers. Dogs weigh some 13–17 kg, bitches approximately 2 kg less.[1] It has a broad chest, strong shoulders, well-boned wide-set legs, a medium length tail carried low, and a broad head with a short muzzle; the ears fold over at the tips and are not cropped.[1][19] The coat is short, stiff and close. It may be white; black, blue, fawn or red, all with or without white; or any variety of brindle, with or without white.[1][41]

It is a healthy and robust dog with a life expectancy of 12–14 years.[14] Neurological disorders identified in the breed include cerebellar abiotrophy, Chiari-like malformation, myotonia congenita and L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria;[42]: 6 hereditary cataracts has also been identified.[43]

The Stafford has a reputation for pugnacity; when challenged by another dog it is known to not back away.[41][44]

Use

Even in the days of blood sports, the Stafford was always a family pet and companion dog, and is even more so today.[19] It is considered loyal, courageous and affectionate, and is among the breeds recommended by the Kennel Club for families.[19][45]

In the decade 2011–2020, annual registrations with the Kennel Club fell from about 7000 to about 5000; in 2019 and 2020 it had the highest number of registrations in the Terrier group.[46] It is among the most frequently registered breeds in Australia, France, and New Zealand.[44][47][48][49] In the United States, it was in 81st place on an American Kennel Club list of registrations by number in 2020.[50]

In 2013, the breed accounted for more than a third of the dogs passing through British shelters such as Battersea Dogs & Cats Home. The breed has been associated with chav culture, which tends to attract the negativity associated with it.[44]

Breed-specific legislation

Modern Staffords are often confused with the fighting pit bull-types because they share common ancestors that date back to the early 1800s when pit fighting was a popular sport. As a result, Staffords are considered among the breeds with a stigma attached relative to the 'chav culture'".[31] In 2018, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) lobbied the British Parliament to have the Staffordshire Bull Terrier added to the list of restricted dog breeds in the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991.[51] The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Kennel Club, Dogs Trust, Blue Cross, and the Battersea Dogs & Cats Home all objected to the proposal. The proposal was inevitably rejected by Parliament;[51] therefore, Staffordshire Bull Terriers are not banned under the UK's Dangerous Dogs Act 1991.[31][52] Globally, pit bull-types including Staffordshire Bull Terriers have made local news for acts of aggression, but valid questions have been raised about the veracity of visual breed identification, and media hype.[53][54]

In the United States, dogs that are often defined as pit bulls and commonly banned in some countries include American Pit Bull Terriers, Staffordshire Bull Terriers, American Staffordshire Terriers, and Bull Terriers.[55] The CDC and ASPCA are among several agencies and organizations that have stood in opposition to the "theory underlying breed-specific laws—that some breeds bite more often and cause more damage than others, ergo laws targeting these breeds will decrease bite incidence and severity" as they do not believe it has been successful in practice.[56] As of June 2017, there were 21 states in the US that prohibited breed-specific legislation.[57][58]

Irish Staffordshire Bull Terrier fiction

In the UK, American Pit Bull Terriers are sometimes advertised as "Irish Staffordshire Bull Terrier" in an attempt to circumvent the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991.[59] The Irish Staffordshire Bull Terrier is not recognised as a breed by the Irish Kennel Club or any other kennel club,[60] and is attributed by the RSPCA to be contributing "to a rise in incidents of dog fighting".

Notable dogs

- Jock – a Staffordshire Bull Terrier cross, subject of Sir Percy FitzPatrick’s book Jock of the Bushveld (1907).[61]

- Cooper – a Staffordshire Bull Terrier adopted in March 2018 by the Staffordshire Police for training as a police dog, the first of this breed in Staffordshire.[62]

- Watchman – military mascot of the Staffordshire Regiment

Gallery

-

Red & white

-

Black

-

White & black

-

Red

-

Brindle

-

Black Brindle

-

Blue

-

Brindle & white

-

Fawn

-

Black Brindle

-

White & black, ears not cropped

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ From Bull-and-Terrier to Bull Terrier - another breed was the Bull Terrier, molded into a distinct breed by James Hinks of Birmingham, England. Hinks presented “New Bull Terrier” at a Birmingham show in May 1862.

Citations

- ^ a b c d e The Kennel Club, Staffordshire Bull Terrier: Breed Standard. The Kennel Club. Archived 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Staffordshire Bull Terrier: description". TheKennelClub.org.uk. The Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021.

- ^ Reznik, Allan (15 June 2020). "What Are the Differences Between the AKC, CKC and UKC Registries? – Dogster". Dogster. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Sfetcu, N. (2014). About Dogs. Nicolae Sfetcu. p. 977-978. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ The Complete Dog Book (16th ed.). New York: American Kennel Club / Howell Book House. 1980. pp. 514–515. ISBN 0876054629.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Flaim, Denise (8 October 2020). "Bull Terrier History: Behind the Breed – American Kennel Club". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Staffordshire Bull Terrier Dog Breed Information". ACK.org. American Kennel Club. 6 November 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Harris, David (2008). Bully breeds. Freehold, NJ: Kennel Club Books. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-59378-664-9. OCLC 172980066.

- ^ "Popular Science". The Popular Science Monthly. Bonnier Corporation: 126. November 1936. ISSN 0161-7370. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Breed History". Staffordshire Bull Terrier Club of America. 5 April 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Larson, Greger; Karlsson, Elinor K.; Perri, Angela; Webster, Matthew T.; Ho, Simon Y. W.; Peters, Joris; Stahl, Peter W.; Piper, Philip J.; Lingaas, Frode; Fredholm, Merete; Comstock, Kenine E.; Modiano, Jaime F.; Schelling, Claude; Agoulnik, Alexander I.; Leegwater, Peter A.; Dobney, Keith; Vigne, Jean-Denis; Vilà, Carles; Andersson, Leif; Lindblad-Toh, Kerstin (21 May 2012). "Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (23). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: 8878–8883. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203005109. ISSN 0027-8424.

- ^ a b c d e f Robinson-Cox, Clare (Hamason) (June 2016). "Linking The Past To The Present–Pt. 1". Stafford Knot, Inc. p. 10. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Staffordshire Bull Terrier to Become A.K.C.' s 121st Registered Breed Oct.1; Manhattan Aide Named". The New York Times. 18 August 1974. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Staffordshire Bull Terrier Dog Breed Information". AKC.org. American Kennel Club. 6 November 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e de Klerk, Joanna (2019). The Complete Guide to Staffordshire Bull Terriers. Isanti, MN: LP Media, Inc. ISBN 978-1-0799-9547-3. OCLC 1237368664.

- ^ "Breed Standards: Bull Terrier". UKCDogs.com. United Kennel Club. 14 April 2007. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "American Staffordshire Terrier Dog Breed Information". AKC.org. American Kennel Club. 6 November 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Zarley, B. David (22 November 2017). "Your Yorkie Was a Killing Machine". Vice. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Staffordshire Bull Terrier: description. The Kennel Club. Archived 16 April 2021.

- ^ a b Hancock, David (2011). Sporting terriers: their form, their function and their future. Ramsbury, Marlborough: The Crowood Press Ltd. pp. 60–66. ISBN 978-1-84797-303-0.

- ^ a b Flaim, Denise (4 February 2021). "American Staffordshire Terrier History: How the AmStaff Separated From the "Pit Bull" – American Kennel Club". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Pearce, Frank (1874). Kennel Club Stud Book. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Horace Cox. p. 535.

- ^ Pearce, Frank (1874). Kennel Club Stud Book. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Horace Cox. p. 515.

- ^ a b Nicolai, Jason (2013). "Evolution of The Staffordshire Bull Terrier Breed Standard" (PDF). The Stafford Knot, Inc. pp. 30–33. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Beaufoy, James (2016). Staffordshire Bull Terriers: a practical guide for owners and breeders. Ramsbury, Wiltshire: Crowood Press. ISBN 9781785000973.

- ^ The Stafford Magazine Winter 1968. January 1968. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ "SBT = Bulldog + Terrier". Issuu. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Cairns, A.W.A. (October 1987). "The Stafford" (PDF). Kennel Gazette. Kennel Club. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Parker, Heidi G.; Dreger, Dayna L.; Rimbault, Maud; Davis, Brian W.; Mullen, Alexandra B.; Carpintero-Ramirez, Gretchen; Ostrander, Elaine A. (2017). "Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development". Cell Reports. 19 (4): 697–708. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.079. PMC 5492993. PMID 28445722.

- ^ Pedersen, Niels C.; Pooch, Ashley S.; Liu, Hongwei (29 July 2016). "A genetic assessment of the English bulldog". Canine Genetics and Epidemiology. 3 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 6. doi:10.1186/s40575-016-0036-y. ISSN 2052-6687. PMC 4965900. PMID 27478618.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Potts, Lauren (24 January 2015). "Staffordshire bull terriers: A question of class?". BBC News. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Olson, K.R.; Levy, J.K.; Norby, B.; Crandall, M.M.; Broadhurst, J.E.; Jacks, S.; Barton, R.C.; Zimmerman, M.S. (2015). "Inconsistent identification of pit bull-type dogs by shelter staff". The Veterinary Journal. 206 (2): 197–202. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.07.019. ISSN 1090-0233. PMID 26403955. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ a b Michael Worboys, Julie-Marie Strange & Neil Pemberton, The invention of the modern dog: breed and blood in Victorian Britain, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018, ISBN 9781421426587.

- ^ a b Read, Tony (2013). The bull terrier in sport and show - history & anecdote. United States: Vintage Dog Books Made available through hoopla. ISBN 978-1-4465-4654-3. OCLC 1098628082.

- ^ "The Staffordshire Bull Terrier and its Ancestors" (PDF). Kennel Club. 20 June 2014. p. 7. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Drabble, Phil (1948). "Staffordshire Bull Terrier". In Vesey-Fitzgerald, Brian (ed.). The Book of the Dog. Los Angeles: Borden Publishing Co. p. 669. Retrieved 2 February 2018 – via Stafford Exchange.

- ^ a b FCI breeds nomenclature: Staffordshire Bull Terrier (76). Fédération Cynologique Internationale. Accessed June 2021.

- ^ a b c "American Staffordshire Terrier Dog Breed Information". AKC.org. American Kennel Club. 6 November 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ a b Flaim, Denise (4 February 2021). "American Staffordshire Terrier History: How the AmStaff Separated from the 'Pit Bull'". AKC.org. American Kennel Club. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Fletcher, Walter R. (19 September 1971). "A Breed That Came Up the Hard Way". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Derek Hall, The ultimate guide to dog breeds: a useful means of identifying the dog breeds of the world and how to care for them, Buntingford: Regency House Publishing Ltd., 2016, ISBN 978-0-7858-3441-0.

- ^ a b Ronaldo C. Da Costa, Curtis W. Dewey (2015). Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology, third edition, ebook. Ames, Iowa: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119062042.

- ^ a b Cathryn S. Mellersh, Louise Pettitt, Oliver P. Forman, Mark Vaudin, Keith C. Barnett (2006). Identification of mutations in HSF4 in dogs of three different breeds with hereditary cataracts. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 9 (5): 369–378. doi:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2006.00496.x

- ^ a b c d Lauren Potts, "Staffordshire bull terriers: A question of class?", bbc.com/news/, published 24 January 2015.

- ^ Cornish, Natalie (26 April 2019). "6 best dog breeds for families with children, according to Kennel Club". Country Living. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ a b Comparative tables of registrations for the years 2011-2020 inclusive. The Kennel Club. Archived 2 June 2021.

- ^ a b News.com.au, "Here’s a list of the most popular dog breeds in Australia in 2017", news.com.au, published 2 February 2017.

- ^ a b Société Centrale Canine, "Le chien de race en 2018 : Bousculades dans le Top 20 du LOF", centrale-canine.fr, published 12 February 2019.

- ^ a b The New Zealand Herald, "The most popular dogs in New Zealand", nzherald.co.nz, published 22 May 2017.

- ^ a b Reisen, Jan (16 March 2021). The Most Popular Dog Breeds of 2020. American Kennel Club. Accessed June 2021.

- ^ a b c Winter, Stuart; "Staffie ban: Britain’s much loved terrier will NOT be outlawed, says minister", express.co.uk, published 18 July 2018.

- ^ "The Dangerous Dogs (Designated Types) Order 1991 No. 1743". www.legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ "Experts say 'pit bulls' don't exist". Washington Post. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "The Most Feared Dogs May Also Be the Most Misunderstood". Adventure. 3 July 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Overview of Breed Specific Legislation (BSL) Ordinances". Animal Legal & Historical Center. 1 January 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Position Statement on Breed-Specific Legislation". ASPCA. 6 September 2006. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "What is a pit bull? (Hint: It's not actually a breed)". TODAY.com. 27 October 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Overview of States that Prohibit BSL". Animal Legal & Historical Center. 1 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b Daniel Foggo and Adam Lusher, "Trade in 'Irish' pit bulls flouts dog law", telegraph.co.uk, published 2 June 2002. (Archived 3 August 2018).

- ^ "Native Breeds of Ireland". The Irish Kennel Club. 16 June 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ a b Sir Percy FitzPatrick, Jock of the Bushveld, London: Longmans & Co., 1907.

- ^ a b Georgia Diebelius, "Dog rescued from streets becomes one of UK's first police Staffies", metro.co.uk, published 19 November 2018.

External links

- Staffordshire Bull Terrier 1935 - Staffordshire Bull Terrier history, statistics, links etc.

- Staffordshire Bull Terrier UK Club - Staffordshire Bull Terrier UK Club

- SBTpedigree - Staffordshire Bull Terrier Pedigree Search Engine