Race of ancient Egyptians

The racial characteristics of ancient Egyptians have been a subject of debate and controversy dating back to 18th century natural history. Ironically, the Egyptians considered themselves part of a distinct race, separate from their neighbors.[1][2]

Mainstream consensus is that black people never lived outside of sub-Saharan Africa prior to the slave trade. However, Afrocentric scholars such as Martin Bernal and Cheikh Anta Diop claim that dynastic Egypt was from its inception – and remained throughout several millennia – a primarily Black civilization.

Background

Race

Modern scientific view

The term race distinguishes one population of an animal species (including human) from another of the same species. The most widely used human racial categories are based on visible traits (especially skin color, facial features and hair texture), genes, and self-identification. Conceptions of race, as well as specific racial groupings, vary by culture and over time, and are often controversial, for scientific reasons as well as because of their impact on social identity and identity politics. Some scientists regard race as a social construct while others maintain it has genetic basis.

Since the 1940s, some evolutionary scientists have rejected the view of race according to which any number of finite lists of essential characteristics could be used to determine a like number of races. For example, the convention of categorizing the human population based on human skin colors has been used, but hair colors, eye colors, nose sizes, lip sizes, and heights have not. Many social scientists think common race definitions, or any race definitions pertaining to humans, lack taxonomic rigour and validity. They argue that race definitions are imprecise, arbitrary, derived from custom, have many exceptions, have many gradations, and that the numbers of races observed vary according to the culture examined. They further maintain that "race" as such is best understood as a social construct, and they prefer to conceptualize and analyze human genotypic and phenotypic variation in terms of populations and clines instead.

Many scientists, however, have argued that this position is motivated more by political than scientific reasons. Others also argue that categories of self-identified race/ethnicity or biogeographic ancestry are both valid and useful, that these categories correspond to clusters inferred from multilocus genetic data, and that this correspondence implies that genetic factors contribute to unexplained phenotypic variation among groups.

Ancient Egyptian view

The Egyptians considered themselves part of a distinct race, separate from their neighbors.[3][4] Most modern Egyptologists believe the Egyptians thought of themselves as Egyptian people, not African, Mediterranean, White, or Black people. They discovered wall paintings that contrast Egyptian [3], Nubian [4], Berber[5], and Semitic peoples [6].

Racism and colonialism

In the 19th century, supporters of slavery and colonialism began to use racism to justify the exploitation of African and Native Americans. They argued that the harsh northern climates had forced Europeans to develop a greater intellect than any other race. They also argued that people such as Sub-Saharan were incapable of living freely in a civilized world and were naturally inclined towards slavery.

Black nationalist and psychoanalyist Frantz Fanon wrote in his book Black Skin, White Masks that the history of white racism, colonialism, and oppression leads blacks, often out of an inferiority complex, to seek out and repond with historical proof of black civilization. He traced this ongoing dialectic and the role it played in his own development:

I rummaged frenetically through all the antiquity of the black man. What I found there took away my breath. In his book L'abolition de l'esclavage Schoelcher presented us with compelling arguments. Since then, Frobenius, Westermann, Delafosse-- all of them white-- had joined the chorus: Segou, Djenne, cities of more than a hundred thousand people; accounts of learned blacks (doctors of theology who went to Mecca to interpret the Koran). All of that, exhumed from the past, spread with its insides out, made it possible for me to find a valid historic place. The white man was wrong, I was not a primitive, not even a half-man, I belonged to a race that had already been working in gold and silver two thousand years ago.

However, he later decided that the issue was not essential to the plight of black people:

Let us be clearly understood. I am convinced that it would be of the greatest interest to be able to have contact with a Negro literature or architecture of the third century before Christ. I should be very happy to know that a correspondence had flourished between some Negro philosopher and Plato. But I can absolutely not see how this fact would change anything in the lives of the eight-year-old children who labor in the cane fields of Martinique or Guadeloupe.

Research

Genetics

The view that ancient Egyptians were Black is strongly challenged by those who argue that the Sahara desert was indeed a major barrier that isolated the populations of sub-Saharan Africa into a unique clearly distinguishable genetic cluster that is separate from populations of North Africa and even some of the populations of East Africa cluster with North Africans because of Caucasoid admixture.

The eminent psychologist Arthur Jensen has also demonstrated that sub-Saharan Africans are a separate genetic cluster, clearly distinguished from Caucasoids and Berbers:

On pgs 430-431 of the g factor Jensen makes reference to the chart to the right, writing:

- Cavalli-Sforza et al. transformed the distance matrix to a correlation matrix consisting of 861 correlation coefficients among the forty-two populations, so they could apply principal components (PC) analysis on their genetic data...PC analysis is a wholly objective mathematical procedure. It requires no decisions or judgments on anyone's part and yields identical results for everyone who does the calculations correctly...The important point is that if various populations were fairly homogeneous in genetic composition, differing no more genetically than could be attributable only to random variation, a PC analysis would not be able to cluster the populations into a number of groups according to their genetic propinquity. In fact, a PC analysis shows that most of the forty-two populations fall very distinctly into the quadrants formed by using the first and second principal component as axes...They form quite widely separated clusters of the various populations that resemble the "classic" major racial groups-Caucasoids in the upper right, Negroids in the lower right, North East Asians in the upper left, and South East Asians (including South Chinese) and Pacific Islanders in the lower left...I have tried other objective methods of clustering on the same data (varimax rotation of the principal components, common factor analysis, and hierarchical cluster analysis). All of these types of analysis yield essentially the same picture and identify the same major racial groupings.

Jensen is not alone in concluding that sub-Saharan Africans form a distinguishable genetic cluster. Noah A. Rosenberg and Jonathan K. Pritchard, geneticists from the laboratory of Marcus W. Feldman of Stanford University, assayed approximately 375 polymorphisms called short tandem repeats in more than 1,000 people from 52 ethnic groups in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. They looked at the varying frequencies of these polymorphisms, and were able to distinguish five different groups of people whose ancestors were typically isolated by oceans, deserts or mountains: sub-Saharan Africans; Europeans and Asians west of the Himalayas; East Asians; inhabitants of New Guinea and Melanesia; and Native Americans.[5] A similar finding was made by Dr. Neil Risch of Stanford University. According to the New York Times:

These five geographically isolated groups, in Dr. Risch's description, are sub-Saharan Africans; Caucasians, including people from Europe, the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East; Asians, including people from China, Japan, the Philippines and Siberia; Pacific Islanders; and Native Americans.[6]

Even the black identity of any Nubian presence in ancient Egypt is contradicted by studies showing modern-day Ethiopians in the Horn of Africa have been found to generally cluster as an intermediate cluster between sub-Saharan Africans and Middle-Easterners (Risch, Tang et al. 2002), reflecting the nation's proximity to Asia and the Middle East. A number of matrilineal genetic studies have detected almost equal sub-Saharan and western Eurasian lineages among the population examined (Kivisild et al. 2004) In addition, today's Nubians do not cluster with sub-Saharan Africans but with North Africans in the African genetic linkage tree above. It should be noted however that North Africans may not be entirely Caucasoid because North African Berbers appear midway between Negroids and Caucasoids in the above Cavali-Sforza chart cited discussed by Jensen.

However a 2004 study of the mtDNA of 58 native inhabitants from upper Egypt found a genetic ancestral heritage to East Africa and West Asia. [7]

From this perspective, the term "Caucasoid" when used to describe Nilotic people such as the Ancient Egyptians and native East Africans such as Ethiopians, is a misnomer. Dr. Shomarka Keita acknowledges that certain traces of modern variation in these populations are due to foreign admixture, as can be seen in the different native and foreign haplotypes in the people of both regions. [8]

Skin color

Some ignore genetic research showing the Sahara desert to be the dividing line between Negroid and Caucasoid populations, and instead define the ancient Egyptians as Black for the simple reason that they may have been dark skinned African natives. However this argument is strongly challenged by research showing that the original inhabitants of Egypt were unlikely to have dark complexions for the simple reason that the skin color of indigenous populations are adapted through natural selection to the climate where they live, and Egypt is not a region that produces dark skin.

Others however argue that the Von Luschan scale of skin color is not an effective way of determining "polygenetic relationships" and "race".

Pigmentation is the most readily visible signifier of race, and as such it's often used by laymen to detect bi-racial ancestry. Yet it's also the least reliable from this standpoint, as it changes in response to climatic and environmental conditions, both seasonal and long-term, and can vary greatly within genetically differentiated populations (i.e. races).

(N. Jablonski and G. Chaplin, J Hum Evol, 2000)[9]

It is also important to note that some evidence suggests migration from the south and south/west near Saharan and Sudanic zones, while previous notions of an outside origin of invading "Caucasoids" for the peopling of Egypt has since been challenged.(SeeDynastic Race Theory) [10] The notion that the Sahara has always been a barrier is challenged by evidence from mainstream studies that suggests a fertile Sahara as recent as 10,000 years ago.[11]

Mummies

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Language

One of the many names for Egypt in ancient Egyptian is km.t (read "Kemet"), meaning "black land". More literally, the word means "something black". The use of km.t "black land" in terms of a place was generally in contrast to the "deshert" or "red land": the desert beyond the Nile valley. When used to mean people, km.t "people of Kemet", "people of the black land" is usually translated "Egyptians". This word that the Egyptians used to describe themselves was never used to describe other peoples of Africa.

Culture

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Art

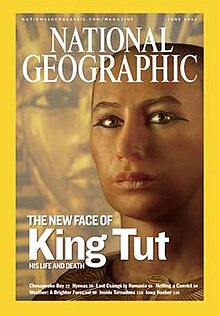

Some scholars have characterized the dolichocephalism of certain Egyptian royalty in the Tutmosid line as "family traits," rather than racial characteristics. Ray Johnson, director of the University of Chicago's research center at Luxor, describes the oddly shaped, quartzite head of an Egyptian princess, thought to be that of Meritaten,[7],[8] the daughter of Akhenaten, as "most likely a family trait exaggerated by the artistic style of the period" and that it "It simply falls within the normal range of human variation." The press release of the Tutankhamun CT scan states:

Tutankhamun had a very elongated (dolichocephalic) skull. The cranial sutures are not prematurely fused, so this is most likely due to normal anthropological variation rather than any pathology. Cleft Palette and Overbite. The king had a small cleft in his hard palette (the bony roof of his mouth), not associated with an external expression such as a hare-lip or other facial deformation. His lower teeth are slightly misaligned. He has large front incisors and the overbite characteristic of other kings of from his family (the Tuthmosid line).[9]

Contrary to earlier scholarship, the exaggeratedly dolichocephalic heads of Amarna artists are thought to be a stylistic affectation meant to accentuate a normal cranial feature, as in the case King Tutankhamen. Further, the king was neither genetically deformed nor the subject of head binding. As a result of CT scans conducted of King Tutankhamun's skull in 2005, it was found that, although "Tutankhamun had a very elongated (dolichocephalic) skull," "The cranial sutures are not prematurely fused...." In fact, with the king's age estimated between 18 and 20 years, "All of the cranial sutures [were] still at least partly open." Head binding affects the way in which cranial sutures fuse and would have been detected by the CT scan. The conclusion by medical experts was that Tut's dolichocephalism was "most likely due to normal anthropological variation...." [10]

The Great Sphinx of Giza

This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. |

Over the centuries, numerous writers and scholars have recorded their impressions and reactions upon seeing the Great Sphinx of Giza. French scholar Constantin-François de Chassebœuf, Comte de Volney visited Egypt between 1783 and 1785. He is one of the earliest known Western scholars to remark upon what he saw as its "typically Negro" countenance.

"...[The Copts] all have a bloated face, puffed up eyes, flat nose, thick lips; in a word, the true face of the negro. I was tempted to attribute it to the climate, but when I visited the Sphinx, its appearance gave me the key to the riddle. On seeing that head, typically negro in all its features, I remembered the remarkable passage where Herodotus says: 'As for me, I judge the Colchians to be a colony of the Egyptians because, like them, they are black with woolly hair. ...'".[11]

Upon visiting Egypt in 1849, French author Gustave Flaubert echoed de Volney's observations. In his travelog chronicling his trip, he wrote:

We stop before a Sphinx; it fixes us with a terrifying stare. Its eyes still seem full of life; the left side is stained white by bird-droppings (the tip of the Pyramid of Khephren has the same long white stains); it exactly faces the rising sun, its head is grey, ears very large and protruding like a negro’s[12], its neck is eroded; from the front it is seen in its entirety thanks to great hollow dug in the sand; the fact that the nose is missing increases the flat, negroid effect. Besides, it was certainly Ethiopian; the lips are thick….[13]

Scientific consensus

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Alternative views

Afrocentrism and Pan-Africanism

Henry Sylvestre-Williams created the Pan African Organization in 1897. One of the organization's stated goals was to "promote and protect the interests of all subjects claiming African descent, wholly or in part, in British colonies and other places especially Africa, by circulating accurate information on all subjects affecting their rights and privileges as subjects of the British Empire, by direct appeals to the Imperial and local Governments."

In 1900, he held the first Pan African Conference. The three-day conference took place on July 23 to July 25. After the conference was over Williams began touring, lecturing, and starting new branches of his Pan African Organization.

One of the attendees of the 1900 conference and the most influential early proponents of Pan-Africanism was W.E.B. Dubois. DuBois researched West African culture and attempted to construct a pan-Africanist value system based on West African traditions. Dubois's ideas were able to reach a wide audience, because of his prolific writing. He wrote weekly columns in the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, the New York Amsterdam News, and the Hearst-owned San Francisco Chronicle. He also worked as Editor-in-Chief of the NAACP publication, The Crisis.

Eurocentrism

Much of the "eurocentric" sentiment and argument concerning Egyptian racial traits stems from thulist or otherwise occult interest in an "Aryan" Egyptian kingdom.

References

- ^ The Civilization Of Ancient Egypt

- ^ http://homelink.cps-k12.org/teachers/filiopa/files/AC383EB269C648AAAA659593B9FC358C.pdf

- ^ The Civilization Of Ancient Egypt

- ^ http://homelink.cps-k12.org/teachers/filiopa/files/AC383EB269C648AAAA659593B9FC358C.pdf

- ^ [[1]]

- ^ [[2]]

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=14748828

- ^ http://www.homestead.com/wysinger/keita.pdf

- ^ http://www.sitesled.com/members/racialreality/skincolor.html

- ^ http://www.historyplace.com/pointsofview/not-out.htm

- ^ http://www.cru.uea.ac.uk/~e118/Fezzan/fezzan_palaeoclim.html

Bibliography

- Noguera, Anthony (1976). How African Was Egypt?: A Comparative Study of Ancient Egyptian and Black African Cultures. Illustrations by Joelle Noguera. New York: Vantage Press.

- Raymond Faulkner. "Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian". Griffith Institute; Rep edition (January 1, 1970) ISBN 0900416327

- James P. Allen. "Middle Egyptian : An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs". Cambridge University Press (November 4, 1999). ISBN 0521774837

External links

- "The evolution of human skin coloration",Department of Anthropology, California Academy of Sciences

- American Anthropological Association Statement on "Race"