Tomboy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

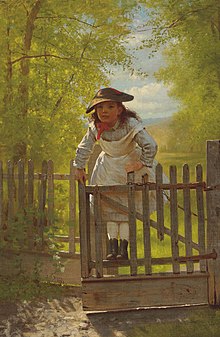

A tomboy is a term for a girl or a young woman with masculine qualities. It can include wearing androgynous or unfeminine clothing and actively engage in physical sports or other activities and behaviors usually associated with boys or men.[1]

Etymology

The word "tomboy" is a portmanteau which combines a common boy's name "Tom" with "boy". Though this word is now used to refer to "boy-like girls", the etymology suggests the meaning of tomboy has changed drastically over time. Records show that Tomboy used to refer to boisterous male children in the mid-16th century.[2]

To understand why the typical male name "Tom" is incorporated in the term tomboy, "Tom" is an abbreviation for the male name "Thomas," and can be utilized as a generic term for men. Slangs invented in the early 16 century, such as “every Tom, Dick, and Harry,” [3] and "Tom of all trades”[3] suggest English speakers utilize “tom” as a generic noun for men, even for male animals, such as “tom cat" and "tom turkey.[3]" In short, “Tom” symbolizes the archetypal male, and thus a tomboy used to be defined as a “rude, boisterous or forward boy” according to the Oxford Dictionary of English in 1533.[4] In the 1570s, however, "Tomboy” soon took on another meaning of a "a bold or immodest woman.[4]" Though it's still uncertain when exactly people begin to associate with the term "tomboy" with "boyish girls" instead of its original descriptive nature for boys, after women challenged the traditional definition of girls' gender roles in the first and second wave of feminism, the term tomboy now refers to sport-spirited, boisterous girls and young woman with often an androgynous or masculine style of dress.[5][3]

History

Pre-16th century and origin

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (September 2022) |

In the United States

Pre-19th century

Before the mid-19th century, femininity was equated with emotional fragility, physical vulnerability, hesitation, and domestic submissiveness, commonly known as the "Cult of True Womanhood".[6] Under the influence of this toxic ideal of femininity, women of all age cinch their waists with corsets so tight and eat so little that they physically cannot engage in strenuous sports or any physical activities.[6] They reduce themselves into feeble ornamental objects for their brothers, husbands, and fathers. This twisted paradigm remained stagnant until the mid-nineteenth century.[6] During the Long Depression when the American government regulation corrupted free trade in the economy, the US's increasing economic instability made fragile femininity, until then quite widespread in the behavioral customs, no longer desirable.[6] Young women must become workforce to support their families and learn practical job skills instead of existing as ornamental beauty, and thus a robust physique was needed to support the physical demands of job practices.[6] This leads to the paradigm shift in people's expectations of young women from languishing, decorative beauty to vigorously healthy, thus laying the groundwork for tomboyism.[6]

In Charlotte Perkin Gilman's book, Women and Economics, the author lauds the health benefits of being a tomboy, that girls should be "not feminine till it is time to be.[7]" Joseph Lee, a playground advocate, wrote in 1915 that a "tomboy phase" was crucial to physical development of young girls between the ages of 8 and 13.[8] Coupled with the birth of first wave feminism and the US's depressed economy, tomboyism amongst young girls emerged because the young girls' parents permitted or even promoted the tomboy upbringing due to the decaying economy and the American turbulent political climate.[6]

Late 19th Century and Civil War

It wasn't until the American Civil War when American society fully realize the importance of healthy women.[9] When hostilities of the North and South broke out and thousands of men fled to the battlefield, many adolescent girls and young women were pushed to be responsible for tasks that would be traditionally considered in the men's realm. Women weren't allowed to have independent bank accounts, but now must take care of the finances.[9] American wives, mothers, and young girls used to rely on the men in the household for security, but now the duty of protecting their homes from the army was on the women's shoulders.[9] As a result, mothers focused on improving their physical constitution of their daughters while taking care of hers.[9] In addition, many women who still believed in or at least didn't rebel against the Cult of True Womanhood before the Civil War found themselves engaging in an array of masculine actions during it.[9] In short, women were given the duties of men during the period of Civil War, leading to tomboyism.

20th Century: Second Wave Feminism and Gay Liberation

While the first wave feminism mainly focused on women's suffrage, the second wave feminism expanded the discussion of gender inequality in areas such as sexuality, family dynamics, workspace, and laws in relation with patriarchy and culture.[10] With the main purpose of critiquing the patriarchal systematic injustice, this movement leaded to abortion victory, ad opened avenues for gender minorities in education, employment, and legal protection against domestic violence. This created space for the gay liberation movement in the 1960s-1980s advocated against the societal shame on gay pride.[11] With the advocates launching gay pride parades in North America, South America, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand, tomboys were liberated from their heteronormative duties of femininity and compulsory heterosexual relationships with men, especially those ones who identify as lesbians.[12]

21st century

Currently, the term tomboy is now used to address a girl who wears unfeminine clothing, actively engage in physical sports, embraces what's often known as "boy toys" such as cars, or other activities usually associated with boys.[1] The term is used less frequently than before in the West mainly because it's now a societal norm for adolescence girls to engage in physical activities, play with peers of the same and opposite gender, and wear comfortable clothing.[13] In other words, tomboy is becoming a societal norm and therefore it's significance is no longer as prominent. Tomboy is used sometimes as a derogatory term to describe the unfeminine behavior of girls, which is a disrespectful gender stereotype towards women.

Psychobehavioral aspects

Child Development

Tomboy can be seen as a phase of gender presentation in adolescence.[14] Some parents might be concerned by the lack of femininity in their child but the tomboy phase is, in fact, crucial to physical development between the ages of 8 and 13, according to Joseph Lee, the playground movement advocate in 1915.[8] Some girls start to embrace femininity as age increases while some persist to be tomboys in adulthood.[14]

Psychologists speculates that childhood tomboy behavior results from young child's innate curiosity combined with family dynamics and imposed societal gender roles and behavioral customs.[15] The preference of athletics and masculine clothing can be explained by adolescent tomboys's curiosity about outdoors and physical games, by which comfortable clothing such as pants and jersey helps to facilitate their physical engagement.[16] Some tomboys may view femininity as a compulsory label pushed on them, which results in negative feelings toward feminine acts.[17] Masculinity may be seen as a defense mechanism against the parental and societal push toward femininity, shaping the child to detest what is typically defined as girl activity.[14] Recent studies even show that some girls are "born tomboys" because of the higher testosterone levels of the mother during pregnancy.[18]

A large proportion of tomboys grow up and start to embrace femininity or heteronormativity by wearing feminine clothing such as dresses and skirts and dating men.[19] Therefore, being a childhood tomboy doesn't determine one's sexual orientation nor life-long gender presentation. Just like how the feminist writer Charlotte Gilman stated in her book, Women and Economics, girls should be "not feminine till it is time to be," having a tomboy phase is ideal for child development by allowing gender explorations and athletic exercise for the body.

Gender Roles

Gender roles and stereotypes

The idea that there are girl activities and clothing, and that there are boy activities and clothing, is often reinforced by the tomboy concept. Tomboyism can be seen as both refusing gender roles and traditional gender conventions, but also conforming to gender stereotypes.[20] The concept may be considered outdated or looked at from a positive viewpoint.[21] Feminine traits are often devalued and unwanted, and tomboys often respond this viewpoint, especially toward girly girls. This can be due in part to an environment that desires and only values masculinity, depending on the decade and geographical region. Idealized male masculinity is atop the hegemony and sets the traditional standard, and is often upheld and spread by young children, especially through children playing with one another. Tomboys may view femininity as having been pushed on them, which results in negative feelings toward femininity and those that embrace it. In this case, masculinity may be seen as a defense mechanism against the harsh push toward femininity, and a reclaiming of agency that is often lost due to sexist ideas of what girls are and are not able to do.[22]

Tomboys are expected in some cultures to one day cease their masculine behavior. In those cultures, usually, during or right before puberty, they will return to feminine behavior, and are expected to embrace heteronormativity. Tomboys who do not do such are occasionally stigmatized, usually due to homophobia. Creed argues that the tomboy's "image undermines patriarchal gender boundaries that separate the sexes", and thus is a "threatening figure".[23] This "threat" affects and challenges the idea of what a family must look like, generally nuclear independent heterosexual couplings with two children.[24]

Gender scholar Jack Halberstam argues that while the defying of gender roles is often tolerated in young girls, adolescent girls who show masculine traits are often repressed or punished.[20] However, the ubiquity of traditionally female clothing such as skirts and dresses has declined in the Western world since the 1960s, where it is generally no longer considered a male trait for girls and women not to wear such clothing. An increase in the popularity of women's sporting events (see Title IX) and other activities that were traditionally male-dominated has broadened tolerance and lessened the impact of tomboy as a pejorative term.[1] As sociologist Barrie Thorne suggested, some "adult women tell with a hint of pride as if to suggest: I was (and am) independent and active; I held (and hold) my own with boys and men and have earned their respect and friendship; I resisted (and continue to resist) gender stereotypes".[25]

In the Philippines, tomboys are masculine-presenting women who have relations with other women, with the other women tending to be more feminine, although not exclusively, or transmasculine people who have relationships with women; the former appears more common than the latter.[26] Women who engage in romantic relationships with other women, but who are not masculine, are often still deemed heterosexual. This leads to more invisibility for those that are lesbian and feminine.[27] Scholar Kale Bantigue Fajardo argues for the similarity between "tomboy" in the Philippines and "tombois in Indonesia", and "toms in Thailand" all as various forms of female masculinity.[26] In China, tomboys are called "假小子" (jiá xiao zi), which literally translates as "pseudo-boy". This term is largely used as a derogatory term to describe those girls with masculine characteristics.[28] Most of the times calling someone a "假小子" is a humiliation which implies that the individual couldn't find a boyfriend.[28] This largely reduces the value of women to only romance and diminishes girl's confidence in working in what's traditionally defined in the "boy's realm.[28]"

Sexual orientation

Association of Tomboyism with Lesbianism

During the 20th century, Freudian psychology and backlash against LGBT social movements resulted in societal fears about the sexualities of tomboys, and this caused some to question whether tomboyism leads to lesbianism.[29] Throughout history, there has been a perceived correlation between tomboyishness and lesbianism.[30][20] For instance, Hollywood films would stereotype the adult tomboy as a "predatory butch dyke".[20] Lynne Yamaguchi and Karen Barber, editors of Tomboys! Tales of Dyke Derring-Do, argue that "tomboyhood is much more than a phase for many lesbians"; it "seems to remain a part of the foundation of who we are as adults".[30][31] Many contributors to Tomboys! linked their self-identification as tomboys and lesbians to both labels positioning them outside "cultural and gender boundaries".[30] Psychoanalyst Dianne Elise's essay in 1995 reported that more lesbians noted being a tomboy than straight women.[32]

Misconception

While some tomboys later reveal a lesbian identity in their adolescent or adult years, behavior typical of boys but displayed by girls is not a true indicator of one's sexual orientation.[33] With raising female liberation and gender-neutral playgrounds (at least in the US) in the 21st century, an increasing number of girls can technically be considered as “tomboys” without being referred as “tomboys” because it is mostly considered normal nowadays for girls to engage in physical activities, play equally with boys, and wear pants, masculine or gender-neutral clothing. The association between lesbianism and tomboyism is not only outdated but also disrespectful to both the girl and the lesbian community.[34]

Representations in media

Fiction

Tomboys in fictional stories are often used to contrast a more girly and traditionally feminine character. These characters are also often the ones that undergo a makeover scene in which they learn to be feminine, often under the goal of getting a male partner. Usually with the help of the more girly character, they transform from an ugly duckling into a beautiful swan, ignoring past objectives and often framed in a way that they have become their best self.[23] Doris Day's character in Calamity Jane is one example of this;[35] Allison from The Breakfast Club is another.[36] Tomboy figures who do not eventually go on to conform to feminine and heterosexual expectations often simply remain in their childhood tomboy state, eternally ambiguous. The stage of life where tomboyism is acceptable is very short and rarely are tomboys allowed to peacefully and happily age out of it without changing and without giving up their tomboyness.[35]

Tomboyism in fiction often symbolizes new types of family dynamics, often following a death or another form of disruption to the nuclear family unit, leading families of choice rather than a descent. This provides a further challenge to the family unit, including often critiques of socially who is allowed to be a family – including critiques of class and often a women's role in a family. Tomboyism can be argued to even begin to normalize and encourage the inclusion of other marginalized groups and types of families in fiction including, LGBT families or racialized groups. This is all due to the challenging of gender roles, and assumptions of maternity and motherhood that tomboys inhabit.[35]

Tomboys are also used in patriotic stories, in which the female character wishes to serve in a war, for a multitude of reasons. One reason is patriotism and wanting to be on the front lines. This often ignores the many other ways women were able to participate in war efforts and instead retells only one way of serving by using one's body. This type of story often follows the trope of the tomboy being discovered after being injured, and plays with the particular ways bodies get revealed, policed and categorized. This type of story is also often nationalistic, and the tomboy is usually presented as the hero that more female characters should look up to, although they still often shed some of their more extreme ways after the war.[35]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Who Are Tomboys and Why Should We Study Them?, SpringerLink, Archives of Sexual Behavior, Volume 31, Number 4

- ^ King, Elizabeth (Jan 5, 2017). "A Short History of the Tomboy". Atlantic. Retrieved Nov 22, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d O’Conner, Patricia (May 22, 2010). "Who is the Tom in tomboy?". Grammarphobia. Retrieved Nov 22, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Abate, Michelle Ann (2015-06-04). "Tomboy". Keywords. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ Davis, Lisa (August 11, 2020). Tomboy: The Surprising History and Future of Girls Who Dare to Be Different. New York: Legacy Lit. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-0316458313.

- ^ a b c d e f g Abate, Michelle Ann (2008-06-28). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-1-59213-724-4.

- ^ Gilman, Charlotte Perkins (1898). Women and Economics. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company. p. 56.

- ^ a b Lee, Joseph (1915). Play in Education. pp. 392–393.

- ^ a b c d e Abate, Michelle Ann (2008-06-28). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Philadelphia, USA: Temple University Press. pp. 24–16. ISBN 978-1-59213-724-4.

- ^ Pike, Kirsten (2011-06-01). "Lessons in Liberation: Schooling Girls in Feminism and Femininity in 1970s ABC Afterschool Specials". Girlhood Studies. 4 (1): 95–113. doi:10.3167/ghs.2011.040107. ISSN 1938-8322.

- ^ McGraw, Sean Heather K. (2018-12-15). The Gay Liberation Movement: Before and After Stonewall. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 978-1-5383-8134-2.

- ^ Root, Maria P. P. (1997-05-20). Filipino Americans: Transformation and Identity. SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-0579-0.

- ^ Hemmer, Joan D.; Kleiber, Douglas A. (1981-12-01). "Tomboys and sissies: Androgynous children?". Sex Roles. 7 (12): 1205–1212. doi:10.1007/BF00287972. ISSN 1573-2762. S2CID 143826710.

- ^ a b c Plumb, Pat; Cowan, Gloria (May 1984). "A developmental study of destereotyping and androgynous activity preferences of tomboys, nontomboys, and males". Sex Roles. 10 (9–10): 703–712. doi:10.1007/BF00287381. ISSN 0360-0025. S2CID 143885856.

- ^ Adegbenro, Adeyinka (2019-11-19). "Why girls become tomboys". Medium. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ JONES, OWAIN (1999-06-01). "Tomboy Tales: The rural, nature and the gender of childhood". Gender, Place & Culture. 6 (2): 117–136. doi:10.1080/09663699925060. ISSN 0966-369X.

- ^ Jennings, Nancy. "Reading the Female Voice of Tris in the Divergent Series". One Choice, Many Petals: Reading the Female Voice of Tris in the Divergent Series. doi:10.4324/9781315691633-11. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Study Suggests That Tomboys May Be Born, Not Made". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ Ahlqvist, Sheana; Halim, May Ling; Greulich, Faith K.; Lurye, Leah E.; Ruble, Diane (2013-09-01). "The Potential Benefits and Risks of Identifying as a Tomboy: A Social Identity Perspective". Self and Identity. 12 (5): 563–581. doi:10.1080/15298868.2012.717709. ISSN 1529-8868. S2CID 143966649.

- ^ a b c d Halberstam, Judith (1998). Female Masculinity. Duke University Press. pp. 193–196. ISBN 0822322439. Archived from the original on 2018-04-29. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

Hollywood film offers us a vision of the adult tomboy as the predatory butch dyke: in this particular category, we find some of the best and worst of Hollywood stereotyping.

- ^ Halberstam, Judith (1988). Female Masculinity. doi:10.1215/9780822378112. ISBN 978-0-8223-2226-9. Archived from the original on 2018-04-29. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ Harris, Adrienne (2000-07-15). "Gender as a Sort Assembly Tomboys' Stories". Studies in Gender and Sexuality. 1 (3): 223–250. doi:10.1080/15240650109349157. ISSN 1524-0657. S2CID 144985570.

- ^ a b Creed, Barbara (2017-09-25), "Lesbian Bodies: Tribades, Tomboys and Tarst", Feminist Theory and the Body, Routledge, pp. 111–124, doi:10.4324/9781315094106-13, ISBN 978-1-315-09410-6

- ^ Proehl, Kristen Beth, 1980-. Battling girlhood : sympathy, race and the tomboy narrative in American literature. OCLC 724578046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Thorne, Barrie (1993). Gender play: boys and girls in school. Rutgers University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-8135-1923-3.

- ^ a b Fajardo, K. B. (2008-01-01). "TRANSPORTATION: Translating Filipino and Filipino American Tomboy Masculinities through Global Migration and Seafaring". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 14 (2–3): 403–424. doi:10.1215/10642684-2007-039. ISSN 1064-2684. S2CID 142268960.

- ^ Nadal, Kevin L.; Corpus, Melissa J. H. (September 2013). ""Tomboys" and "baklas": Experiences of lesbian and gay Filipino Americans". Asian American Journal of Psychology. 4 (3): 166–175. doi:10.1037/a0030168. ISSN 1948-1993.

- ^ a b c ""女汉子"与"假小子"-商务印书馆英语世界". www.yingyushijie.com. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ Abate, Michelle Ann (2008). Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-722-0.

- ^ a b c Brown, Jayne Relaford (1999). "Tomboy". In B. Zimmerman (ed.). Encyclopedia of Lesbian Histories and Cultures. Routledge. pp. 771–772. ISBN 0815319207. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

The word [tomboy] also has a history of sexual, even lesbian, connotations. [ ... ] The connection between tomboyism and lesbianism continued, in a more positive way, as a frequent theme in twentieth-century lesbian literature and nonfiction coming out stories.

- ^ Yamaguchi, Lynne and Karen Barber, ed. (1995). Tomboys! Tales of Dyke Derring-Do. Los Angeles: Alysson.

- ^ King, Elizabeth (2017-01-05). "A Short History of the Tomboy". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2017-01-08. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- ^ Gabriel Phillips & Ray Over (1995). "Differences between heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women in recalled childhood experiences". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 24 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1007/BF01541985. PMID 7733801. S2CID 23296942.

- ^ Craig, Traci (October 2011). "Tomboy as Protective Identity". Journal of Lesbian Studies. 15 (4): 450–465. doi:10.1080/10894160.2011.532030. PMID 21973066. S2CID 35791467.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d Proehl, Kristen Beth, 1980–. Battling girlhood : sympathy, race and the tomboy narrative in American literature. OCLC 724578046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "She's Not All That: A Brief History of Rags-to-Princess Makeovers in Movies". KQED. 2017-08-24. Archived from the original on 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2019-11-24.