Rebecca Primus

Rebecca Primus | |

|---|---|

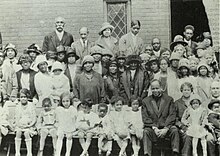

Only known photograph of Primus, 2nd row in the middle, wearing large hat with flowers or ruffles | |

| Born | Rebecca Primus July 10, 1836 Hartford, Connecticut |

| Died | February 21, 1932 (aged 95) Hartford, Connecticut |

| Other names | Rebecca Thomas |

| Occupation | Teacher |

| Years active | 1860–1932 |

Rebecca Primus (July 10, 1837 – February 21, 1932) was a free Black woman from Connecticut and is one of the few Black women whose work in Reconstruction programs has been documented. Her life offers insight into the differences and similarities between free people and former slaves in the North and South and their experiences with racism and sexism in the period between the American Civil War and the Great Depression.

Primus was born into a prominent Black family in Hartford, Connecticut, and attended the First African School, located in the basement of the Talcott Street Congregational Church. After graduating in 1853, she opened a private school in her home. She taught there until 1865, when she was selected as one of the first two teachers and the only Black one from Hartford to go to the South to participate in the Freedmen's Bureau program to educate recently freed slaves. She established the first school for Black students in the local church of Royal Oak, Maryland, and within two years raised sufficient funds to build a separate school, named the Primus Institute in her honor. She taught there until 1869, when the Freedmen's Bureau was dissolved and funding ran out. Returning to Hartford, she worked as a seamstress and taught Sunday school at the Talcott Street church. In 1870, as the first woman to hold a management post at the church, she was appointed assistant to the superintendent of Sunday school. She served until her marriage in 1873, and after a period of some years, returned to the position in 1881.

From 1859 to 1868, Primus wrote letters to her romantic friend, Addie Brown. Although Brown's side of the correspondence has been preserved, Primus's letters have not been found. She also wrote to her own family, discussing her insights into both the communities of Royal Oak and Hartford. Most of her papers were acquired by the Connecticut Historical Society in Hartford in 1934 and an additional group of correspondence to her was obtained by Harvard University's Schlesinger Library in 2017. The letters have been studied by numerous scholars as they provide a rare glimpse of the Black community from an insider's point of view.

Early life and education

Rebecca Primus was born on July 10, 1836,[Notes 1] in Hartford, Connecticut, to Mehitable Esther (née Jacobs), known as Hettie, and Holdridge Primus.[2][3][4] Her younger siblings were Nelson, Henrietta, and Isabella "Bell".[2] Her family were prominent members of Hartford's Black community.[5] Holdridge worked at Humphrey and Seyms as a grocery clerk. Mehitable was a seamstress,[6] who taught other young women to sew and worked as a midwife.[7] She also helped members of the Black community, providing boarding rooms and employment networks, particularly for young women.[8] Holdridge's maternal grandfather, Gad Asher, was kidnapped from Guinea, West Africa, in the 1740s and transported to Connecticut by slave traders. There he was sold to a man named Bishop and taken to East Guilford.[9] Called into military service in 1777, Bishop used a legal loophole that allowed a slave owner to forgo military service by sending a slave to go in his place.[10] Asher enlisted and served from 1777 to 1783, using his military pension to purchase his freedom. Once free, he married a free Black woman and moved to Branford, where he worked as a farmer.[11] Mehitable's father, Jeremiah Jacobs, Sr. was the first free Black man to settle in Hartford. He was a self-employed cobbler.[6][12]

The family were members of the Talcott Street Congregational Church,[6] whose pastor was the former slave and abolitionist, James W. C. Pennington. Pennington and his wife Harriet (née Walker) also taught at the school attended by the Primus children,[13] known as the First African School, and located in the church basement.[13] Primus began attending at the age of five, and after the Penningtons, was taught by Augustus Washington and Selah Africanus.[14] The school was underfunded and lacked adequate textbooks, relying on the instructors to supplement the available reading materials.[15] An avid reader, Primus read novels and literary works, history books and biographies, religious texts, and the Black press. The family made excursions to Boston, New York, and Philadelphia to hear music and cultural presentations.[16] In 1849, they bought a house at 20 Wadsworth Street.[6][17] The house was mortgaged and in hopes of paying it off, Holdridge agreed to go with his employer, C. N. Humphrey, to the California gold fields. Holdridge was in California from 1849 to 1853, leaving Mehitable to care for the family in his absence.[18] Although he did not find gold, Holdridge worked for Alvin Adams's delivery company in Sacramento and was able to secure funds for his passage home and pay off the mortgage.[19] By the time that he returned to Connecticut, Primus had completed her schooling.[20]

Primus's approach to life was careful and exacting, backed by high standards for both herself and her community. She was proud of her intellect and her ability to earn a living. As she saw it as a moral duty to uplift her community, she tried to be a role model. Whatever the consequences, she treated White people with respect only if they gave respect to her.[21][22] She enjoyed learning and the company of teachers and intellectuals.[23] Primus was class conscious and strove to live as a respectable woman.[21] She believed it was her duty to actively help others become educated, find suitable employment, and learn about their rights.[24] An avid church-goer, she attended services weekly and read the Bible every day. In her later years, she was described by friends and neighbors as having a saintly demeanor.[4]

Career

Primus, who assisted in the education of her younger siblings, opened a private school for girls in the family home by 1860.[25] Around this time, she befriended Addie Brown, who had possibly been boarding with the family for a while.[8] Their friendship became so close that Mehitable acknowledged, when questioned by friends about their relationship, that had one of them been a man, they would have married.[26][27] During this period, Primus also wrote poetry and at least one essay, which were preserved in her papers.[14][28]

At the end of the American Civil War (1863), the country entered the reconstruction era and legislation was passed in 1865, to establish a social-welfare program to assist former slaves in transitioning from bondage to a life of freedom. The Freedmen's Bureau, under the authority of the war department, coordinated the assistance programs offered to freedmen.[29] That year, Primus was one of two teachers selected by Calvin Stowe, husband of Harriet Beecher Stowe and head of the Freedmen's Aid Society of Hartford, to participate in the Freedmen's Bureau program to educate southern Black students.[30][Notes 2] The society eventually sent three other teachers south, but Primus was the only Black educator from Hartford.[31] She took a train from Hartford to New York City in November 1865, and then made her way through Jersey City and Philadelphia, before arriving in Baltimore.[32] There, the forty-seven Black teachers and thirty-one White ones were segregated by race and assigned to schools by the Freedmen's Aid Society of Baltimore.[33] Within a week, she was aboard a boat and headed to the village of Royal Oak, Maryland.[34]

Primus was provided with room and board by Charles and Sarah Thomas. Charles was appointed as a trustee of the school Primus was to establish.[35] He was born in 1834 and belonged to Mrs. Richard Adams of Talbot County, Maryland. He purchased his manumission in 1859 and worked as a horse trainer on the estate of Edward Lloyd, who had owned a property where Frederick Douglass was enslaved.[36][37] Within a month, Primus opened the school in the local Black church,[38] initially teaching thirty-six students.[39] Soon she had seventy-five, both children and adults,[40] of whom very few could read or knew the alphabet. Very quickly the students were reading and advanced to learn writing and to study geography and mathematics.[39] Primus also introduced sewing for the girls and oration and music for all of her pupils.[41] In addition to her educational work, she set up a Sunday school and did all the administrative work required to report to the three agencies supervising her work: the Freedman's Bureau and the Freedman's Aid Societies of Baltimore and Hartford.[42]

Primus set about collecting funds and materials to build a separate school building. When negotiations with a White landowner failed, Thomas provided a parcel of his own land for the project.[43] The Freedmen's Aid Society of Hartford provided lumber and the women of the Talcott Street Congregational Church held fundraisers to pay for its construction.[44][45] Other lumber was secured through the Baltimore Freedman's Aid Society and the Freedman's Bureau provided desks for the students.[46] By November 1867, the school was completed and after a vote by the community at its dedication was named the Primus Institute.[47] The Freedman's Bureau was dissolved by the US Congress in 1869. Lacking funds to continue the work, Primus returned to Connecticut,[42] although the school continued to operate in her absence.[48] She discovered that in her absence Black and White schools had been merged, but only White teachers were eligible for employment.[49] She secured work as an agent for a publishing company in 1870.[50] That year, she also was appointed as an assistant to the superintendent of Sunday School at the Talcott Street Church. It was the first time that a woman had been appointed to manage the church's affairs. She remained in the post until 1873.[51]

Around 1872, Thomas moved north alone, no longer married.[37][52][Notes 3] He and Primus married on March 25, 1873, and rented a home near her parents.[52] They had a son Ernest Primus Thomas in 1875, who died seven months later.[54] Thomas initially worked as a gardener for Albert Day, then as a self-employed gardener,[36] but a head injury left him unable to work consistently and he remained partially disabled for the remainder of his life. After Thomas's injury, Primus became the primary wage earner for the family and worked with her mother as a seamstress.[52] In 1881, Primus returned to her position as assistant superintendent of the Talcott Street Church's Sunday School.[51] Thomas served as the doorkeeper for the Connecticut State Senate until 1886.[36] He died in Hartford in 1891[36] and after his death, Primus returned to the family home on Wadsworth Street.[6] Her father had died in 1884,[55] and when her mother died in 1899, their home was sold. Primus moved in with her sister Bell and her husband William Edwards' family,[56] at 115 Adelaide Street.[57] She taught Sunday School classes at the Talcott Street Church until her death.[6]

Death and legacy

Primus died in Hartford on February 21, 1932,[58] and was buried in Zion Hill Cemetery in her family's plot.[1][58] Most of Primus's papers were acquired by the Connecticut Historical Society in Hartford in 1934.[59][60] A dress that she wore, possibly her wedding dress, is owned by the Wadsworth Atheneum.[61] In 2017, the Schlesinger Library of Harvard University acquired a collection of forty-one additional letters which had been written to Primus.[62][63] Although history has typically failed to reflect that Black women participated in the programs of Reconstruction, even in the work Black Reconstruction in America by W. E. B. Du Bois, Primus's life provides evidence of the importance of Black women who went to The South as teachers for newly freed slaves. Their roles extended beyond the schoolhouse and into the homes of community members to uplift and encourage Black people.[2] According to scholar Barbara Beeching, Primus was the only Black teacher sent from Hartford during Reconstruction.[42]

As there had previously been no schoolhouse for Black students, Primus founded the first school for African Americans in Royal Oak, Maryland, and it was named after her, which would have been highly unusual.[42] The Primus Institute continued to operate as a school until 1929.[48] The building that was believed to be the Primus Institute stood in Royal Oak until damaged by two arsons in 2000,[31][Notes 4] which forced its demolition because the Maryland Historical Trust was unable to secure restoration funding or listing on the National Register of Historic Places.[65][66] In 1992, the board of directors of the women's shelter and transitional housing facility "My Sister's Place" in Hartford, decided to name their apartments after prominent Hartford women. Primus was among the first seven women to be honored with her name on one of the twenty units.[40]

The letters

Because of negative stereotypes of Black women, it has been historically rare that their personal details were made public.[59] From the 1970s when new fields of study were created,[67][68] increased scholarship on women and non-White people has disproved myths that Black women did not leave records, keep diaries and journals, or write letters.[59] In the papers acquired by the Connecticut Historical Society are sixty letters from Primus to her family, one hundred and fifty letters from Brown to Primus,[69][Notes 5] over the period from 1859 to 1868, and twenty-four letters from Nelson Primus.[5][61][Notes 6] The letters provide an insight into the personal thoughts, political consciousness, encounters with racism and sexism and the public and private lives of ordinary black women between the Reconstruction era and Great Depression.[70] The letters present an unfiltered glimpse into the lives of Primus and Brown as they were not written like slave narratives or works created during the Harlem Renaissance to be consumed by a White audience.[69] The authors of the letters were neither former slaves, nor abolitionists, but dealt with both the repercussions of segregation and patriarchy.[71]

Numerous scholars and writers have evaluated the letters,[72] and concluded that they showed love and desire in historic contexts that do not necessarily fit into the current constructs of sexuality.[71][73][74] They do not reinforce historic stereotypes of Black women's sensuality. Primus and Brown were neither promiscuous harlots nor asexual, nurturing mammies.[71] The letters show that they had an intense friendship which was similar in many ways to other romantic friendships in the nineteenth century, characterized by professions of love, affection, and strong emotional ties. In other ways they differ, as they speak of their sisterhood and bonds of community, efforts at racial uplift, as well as making "explicit references to erotic interactions" between the two women.[75] Sociologist Karen Hansen, noted that what she called "bosom sex",[76][77] and what historian Leila J. Rupp termed "touching of the breasts",[78] was clear in its eroticism and unlikely to be found in White romantic narratives of the period.[76] However, in the absence of Primus's letters to Brown, the true nature of their relationship is difficult to assess.[5] The letters are significant because they illustrate the complexity of human relationships of their era.[74][79] They are also important documents in broadening the historical understanding of northern Black women, free people of color, and women writers.[79]

Notes

- ^ Date calculated from age at death, 95 years 7 months 11 days.[1]

- ^ According the Beeching, the teachers who were selected by the society were required to meet the requirements of normal school education and pass an examination. It is unknown how Primus acquired the credentials required.[30]

- ^ David O. White, who directed the museum of the Connecticut State Library and worked as an archivist for the Connecticut Historical Commission,[31] noted that when he visited Royal Oak in the 1970s, he could find no evidence of the death of Sarah Thomas. He discovered that she had deeded her portion of the property she jointly owned with Charles to him in 1871. Charles then handed over management of the property in December to William Tilgham and instructed him to pay off any debts owed on it and collect the rents. Thomas family recollections were that he then abandoned Sarah who died of a broken heart. White stated, "My personal journey in the study of Rebecca and her values makes me believe that somewhere in the records of Maryland is a different explanation".[53]

- ^ Local historians verified that the building that burned matched the dimensions described in Primus's letters and reported that the building had been reported as a school house through the 1920s. They were unable to positively identify the burned structure as the Primus Institute,[42] primarily because land records did not refer to it by that name, but instead as "black school" #2. The building, originally stood on Hopkins Neck Road, where a cemetery is now located and may have been moved.[48] Students who attended the school in the 1920s knew it only as the Royal Oak School.[64]

- ^ Primus's letters to Brown have not been located.[5][69]

- ^ Brown died January 11, 1870.[5]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Hale 1937, p. 205.

- ^ a b c Griffin 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 31.

- ^ a b White 1999, p. 283.

- ^ a b c d e Holladay 1999, p. H3.

- ^ a b c d e f Griffin 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 42.

- ^ a b Griffin 1999, p. 18.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Beeching 1996, p. Northeast-17.

- ^ a b Beeching 2016, p. 47.

- ^ a b Beeching 2016, p. 109.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 52, 65.

- ^ Griffin 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Beeching 1996, p. 17.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 65.

- ^ a b Hansen 1996, p. 181.

- ^ Griffin 1999, p. 15, 99-100.

- ^ Hansen 1994, p. 45.

- ^ Griffin 1999, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 65, 72.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Rupp 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Griffin 1999, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Bean 2016, p. 1.

- ^ a b Beeching 2016, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Dunn 2001b, p. 1A.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 111.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 113.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d The Hartford Courant 1891, p. 1.

- ^ a b Griffin 1999, p. 77.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 120.

- ^ a b Dunn 2001d, p. 1A.

- ^ a b Neyer 1992, p. C3.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 122.

- ^ a b c d e Dunn 2001d, p. 13A.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 124.

- ^ The Hartford Courant 1867a, p. 8.

- ^ The Hartford Courant 1867b, p. 8.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 125.

- ^ The Hartford Courant 1867c, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Dunn 2001b, p. 13A.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 172.

- ^ The Hartford Courant 1870, p. 2.

- ^ a b Beeching 2016, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Beeching 2016, p. 177.

- ^ White 1999, p. 281.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 178.

- ^ White 1999, p. 282.

- ^ Beeching 2016, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Correia 2022.

- ^ a b The Hartford Courant 1932, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Griffin 1999, p. 3.

- ^ White 1999, p. 284.

- ^ a b Beeching 1996, p. Northeast-12.

- ^ Englehart & Sinclair 2017.

- ^ Swann Galleries 2017.

- ^ Dunn 2001c, p. 1A.

- ^ Dunn 2001a, pp. 1A, 11A.

- ^ The Star-Democrat 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Lerner 1988.

- ^ Asante & Mazama 2005, p. xxvii.

- ^ a b c Griffin 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Griffin 1999, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c Griffin 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. xvi.

- ^ Beeching 2016, p. 141.

- ^ a b Battle & Bennett 2008, p. 414.

- ^ Griffin 1999, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Sueyoshi 2010, p. 160.

- ^ Hansen 1996, p. 183.

- ^ Rupp 2002, p. 51.

- ^ a b Griffin 1999, p. 7.

Bibliography

- Asante, Molefi Kete; Mazama, Ama (2005). "Introduction". In Asante, Molefi Kete; Mazama, Ama (eds.). Encyclopedia of Black Studies. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publishing. pp. xxv–xxxii. ISBN 978-0-7619-2762-4.

- Battle, Juan J.; Bennett, Natalie D. A. (2008). "25. Striving for Place: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People". In Hornsby, Alton Jr.; Aldridge, Delores P.; Hornsby, Angela M. (eds.). A Companion to African American History (paperback ed.). Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 412–446. ISBN 978-1-4051-7993-5.

- Bean, Christopher B. (2016). Too Great a Burden to Bear: The Struggle and Failure of the Freedmen's Bureau in Texas. New York, New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-6875-7.

- Beeching, Barbara (February 25, 1996). "Finding Rebecca Primus". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. pp. 10, 11, 12, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, Section: Northeast. Retrieved May 30, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Beeching, Barbara J. (2016). Hopes and Expectations: The Origins of the Black Middle Class in Hartford. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-6166-3.

- Correia, Elizabeth (February 13, 2022). "The Lives of Addie Brown and Rebecca Primus Told Through their Loving Letters". connecticuthistory.org. Middletown, Connecticut: Connecticut Humanities. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- Dunn, Travis (February 27, 2001). "Primus Institute: Part 1". The Star-Democrat. Easton, Maryland. p. 1A, 11A. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Dunn, Travis (February 28, 2001). "Primus Institute: Part 2". The Star-Democrat. Easton, Maryland. p. 1A, 13A. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Dunn, Travis (March 1, 2001). "Primus Institute: Part 3". The Star-Democrat. Easton, Maryland. p. 1A. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Dunn, Travis (March 2, 2001). "Primus Institute: Part 4". The Star-Democrat. Easton, Maryland. p. 1A, 13A. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Englehart, Anne; Sinclair, Jehan (July 2017). "Papers of Rebecca Primus, 1854–1872". Hollis Archives. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Schlesinger Library. Archived from the original on May 25, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- Griffin, Farah Jasmine, ed. (1999). Beloved Sisters and Loving Friends: Letters from Rebecca Primus of Royal Oak, Maryland, and Addie Brown of Hartford, Connecticut, 1854–1868. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-45128-0.

- Hale, Charles R. (1937). "Zion Hill Cemetery". In Hale, Charles R.; Babin, Mary H. (eds.). Connecticut Headstone Inscriptions. Vol. 20. Hartford, Connecticut: Connecticut State Library for the Works Progress Administration. pp. 101–229 (continued from Volume 19, pages 29–100). – via FamilySearch (subscription required)

- Hansen, Karen V. (1994). A Very Social Time: Crafting Community in Antebellum New England. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08474-2.

- Hansen, Karen V. (1996). "12. 'No Kisses Is Like Youres': An Erotic Friendship between Two African-American Women during the Mid-Nineteenth Century". In Vicinus, Martha (ed.). Lesbian Subjects: A Feminist Studies Reader. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 178–208. ISBN 978-0-253-33060-4.

- Holladay, Cary (September 5, 1999). "Letters a Rare Glimpse of Black Women's Lives in 1800s". The Commercial Appeal. Hartford, Connecticut. p. H3. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Lerner, Gerda (April 1, 1988). "Priorities and Challenges in Women's History Research". Perspectives on History. Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association. Archived from the original on October 21, 2022. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- Neyer, Constance (March 23, 1992). "Center Honors City Women by Naming Apartments after Them". Hartford Courant. Memphis, Tennessee. p. C3. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Rupp, Leila J. (2002). A Desired Past: A Short History of Same-Sex Love in America (Paperback ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73156-8.

- Sueyoshi, Amy (2010). "12. Finding Fellatio: Friendship, History, and Yone Noguchi". In Masequesmay, Gina; Metzger, Sean (eds.). Embodying Asian/American Sexualities (Paperback ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 157–172. ISBN 978-0-7391-2904-3.

- White, David O. (1999). "Rebecca Primus in Later Life". In Griffin, Farah Jasmine (ed.). Beloved Sisters and Loving Friends: Letters from Rebecca Primus of Royal Oak, Maryland, and Addie Brown of Hartford, Connecticut, 1854-1868. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 279–284. ISBN 978-0-679-45128-0.

- "A School House in Maryland". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. January 30, 1867. p. 8. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Charles H. Thomas". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. August 3, 1891. p. 1. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Fair for the Freedmen". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. February 7, 1867. p. 8. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mrs. Rebecca Thomas". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. February 22, 1932. p. 4. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Personal Beauty". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. January 20, 1870. p. 2. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Paper Seeks Information about Hopkins Neck Road Cemetery". The Star-Democrat. Easton, Maryland. May 22, 2006. p. 15. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Primus Institute". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. November 7, 1867. p. 8. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Printed & Manuscript African Americana – Sale 2441 – Lot 306: More Letters to Rebecca Primus". catalogue.swanngalleries.com. New York, New York: Swann Galleries. March 30, 2017. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- 1836 births

- 1932 deaths

- 19th-century African-American educators

- 19th-century African-American women writers

- 19th-century American writers

- 19th-century African-American writers

- 19th-century American women writers

- 19th-century American educators

- 19th-century American women educators

- 19th-century letter writers

- African-American schoolteachers

- American letter writers

- American tailors

- Freedmen's Bureau schoolteachers

- Writers from Hartford, Connecticut

- Educators from Hartford, Connecticut

- Same-sex relationship

- Women letter writers

- Writers from Connecticut