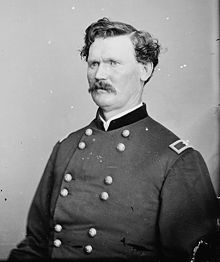

Robert Kingston Scott

Robert Kingston Scott | |

|---|---|

| |

| 74th Governor of South Carolina | |

| In office July 6, 1868 – December 7, 1872 | |

| Lieutenant | Lemuel Boozer Alonzo J. Ransier |

| Preceded by | James Lawrence Orr |

| Succeeded by | Franklin I. Moses, Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 8, 1826 Armstrong County, Pennsylvania, US |

| Died | August 12, 1900 (aged 74) Napoleon, Ohio, US |

| Resting place | Glenwood Cemetery, Napoleon, Ohio |

| Political party | Republican |

| Profession | physician, lawyer |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States Union |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1868 |

| Rank | Brigadier General Brevet Major General |

| Commands | 68th Ohio Infantry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Robert Kingston Scott (July 8, 1826 – August 12, 1900) was an American Republican politician, the 74th governor of South Carolina, and an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. In 1891 he built a Queen Anne Italianate Victorian home in Napoleon, Ohio and lived there until his death in 1900. It still stands to this day in Napoleon on the corner of W. Clinton Street and Haley Ave.

Early life and career

Robert K. Scott was born in Armstrong County, Pennsylvania, to a military family. His grandfather fought in the American Revolution and his father in the War of 1812. Scott studied medicine and began practice in Henry County, Ohio. While in Ohio he became a member of the anti-slavery group called the Liberty Party.

Civil War

In October 1861, Scott became lieutenant colonel of the 68th Ohio Infantry, and colonel of that regiment in 1862. He served in Tennessee, where he commanded the advance of Major General John A. Logan's division on the march into Mississippi. He was engaged at Port Gibson, Raymond, and Champion Hill.

He was afterward at the head of a brigade in the XVII Corps, and was taken prisoner near Atlanta. There are conflicting claims about how he gained freedom. Some claim he was part of a prisoner exchange on September 24, 1864 and was put into Sherman's operations before that city and in the march to the sea, while records also indicate that he escaped by jumping from a prisoner train.

Scott was commissioned as a brigadier general of volunteers on January 12, 1865, and also received the brevet ranks of brigadier and major general in the volunteer army, to date from January 26, and December 2, 1865, respectively.

Postbellum activities

Between 1865–68, General Scott was assistant commissioner of the South Carolina Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, popularly known as the Freedmen's Bureau. In July 1868, he resigned from the Regular Army and entered politics.

Governor of South Carolina

Later that year, he became the first governor of the reconstructed South Carolina as a Republican. In 1870, the South Carolina Constitution of 1868 lifted the rule that had until then prevented a governor's re-election until four years had passed since leaving office. This allowed Scott to become the first governor of South Carolina to be elected to two consecutive terms. He was re-elected by a majority of 33,534 votes of a total 136,608. During his time in office, Klan violence reached an all-time high, while simultaneously the federal government was attempting to withdraw force from South Carolina so as to return the state to "normalcy," this combination left Scott in an untenable position. The majority of those voting for Scott in both of his elections were newly freed African-American Freedmen, South Carolina whites remained overtly and overwhelmingly hostile to him during his entire time in office.[1] His political allies such as African-American leader Benjamin F. Randolph were assassinated by the Klan.[2] Governor Scott took the step of arming African-Americans. He formed militias to defend the Republican government of the state and the militias were legally opened to anyone, however, South Carolina whites refused to join them, as a result they in effect became "black militias." In most of these militias the officers were white officers who had fought in the Union Army during the war, and in some cases were educated African-Americans from northern states who had moved to the state to work in the Freedmen's Bureau after the war.[3] Scott got support from President Ulysses S. Grant, however the rest of the military and northern ambivalence in general hampered his efforts.[4] In Colleton County, Charleston, Columbia, Georgetown County and Beaufort County (which at the time included what is today Jasper County as well) Scott had enough federal troops to effectively police the situation, keep the Klan and general white violence at bay, and ensure free and fair elections. However, in Upstate South Carolina and a large handful of other rural areas he did not.[5]

Judge Richard B. Carpenter testified in an 1872 congressional hearing that voter fraud was involved in Scott's re-election, but Scott remained in office. Ironically, Carpenter not only owed him money at the time, but also continued to ask for more with the promise of political favors in return.[6][full citation needed]

Franklin J. Moses, Jr., the first governor after him, claimed Scott "fraudulently signed state bonds in the St James Hotel in New York under the joint influence of alcohol and burlesque queen Pauline Markham," known as one of "The British Blondes." He also regularly borrowed money from Scott.[7]

Wade Hampton III, the third governor after Scott, who came to power as a result of a racist terrorist campaign led by the Red Shirts militia, indicted him for allegedly "fraudulently issuing three warrants for $48,645 to non-existent payees in 1871." At the same time, he sent letters to Scott promising not to extradite him nor force him to stand trial.[8] [MSS 176]

Return to Ohio

In 1877 Scott returned to Napoleon, Ohio, when Democrats returned to power in the South Carolina executive, possibly out of fear of assassination.

He settled down with his family, including his only son, R.K. Scott, Jr., who was known as "Arkie" because of his initials. On Christmas Day, 1880, 15-year-old Arkie went missing. He was "inclined to frequent taverns."[9] Scott suspected he was hiding in the apartment of his friend Warren G. Drury, aged 23. When Drury refused to let him in, Drury was shot by a bullet from Scott's pistol and died the next day. Scott claimed his weapon accidentally discharged, and the subsequent murder trial consumed national attention. On November 5, 1881, he was acquitted of murder.

Scott died in Napoleon and was buried in Henry County, Ohio.

See also

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- List of Ohio's American Civil War generals

- Ohio in the American Civil War

Notes

- ^ State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina by Richard Zuczek pg. 59

- ^ State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina By Richard Zuczek pg. 57

- ^ State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina By Richard Zuczek pg. 74

- ^ State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina By Richard Zuczek pg. 72

- ^ State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina By Richard Zuczek pg. 79-89

- ^ MSS 176, "The Scott Papers"

- ^ MSS 176

- ^ State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina By Richard Zuczek pg. 193-210

- ^ Henry County, Volume 2

External links

- 1826 births

- 1900 deaths

- 19th-century American politicians

- People from Armstrong County, Pennsylvania

- Republican Party governors of South Carolina

- University of South Carolina trustees

- Union Army generals

- People of Ohio in the American Civil War

- American Civil War prisoners of war held by the Confederate States of America

- People from Napoleon, Ohio

- Ohio Republicans