Joseph Sprigg

Honorable Joseph Sprigg | |

|---|---|

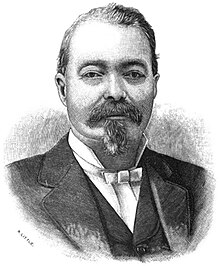

Engraved portrait of Sprigg, 1890 | |

| 6th Attorney General of West Virginia | |

| In office January 1, 1871 – December 31, 1872 | |

| Governor | William E. Stevenson John Jeremiah Jacob |

| Preceded by | Aquilla B. Caldwell |

| Succeeded by | Henry M. Mathews |

| Member of the West Virginia House of Delegates from the 2nd Delegate District | |

| In office January 9, 1889 – January 14, 1891 | |

| Preceded by | J. J. Chipley |

| Succeeded by | C. L. Campbell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 1835 "Swan Ponds", Hampshire County, Virginia (present-day West Virginia) |

| Died | November 3, 1911 (aged 76) Cumberland, Maryland |

| Resting place | Rose Hill Cemetery, Cumberland, Maryland |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Mary Ellen Stubblefield Sprigg |

| Relations | John Van Lear McMahon (uncle) James Sprigg (uncle) Michael Sprigg (uncle) Clement Vallandigham (uncle) John A. McMahon (brother-in-law) |

| Children | Ellen "Nellie" Bell Sprigg Jane Duncan Sprigg Beall Ada Beckham Sprigg Griffith Mary McMahon Sprigg |

| Parent(s) | Joseph Sprigg (father) Jane Duncan McMahon Sprigg (mother) |

| Residence(s) | Moorefield, West Virginia Cumberland, Maryland |

| Profession | Lawyer and politician |

Joseph Sprigg [a] (October 1835 – November 3, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician in the U.S. state of West Virginia. Sprigg served as the sixth Attorney General of West Virginia from January 1, 1871, until December 31, 1872, and was the first Democrat to serve in the post. Sprigg was an organizer of the Democratic Party of West Virginia and the West Virginia Bar Association, of which he served as its inaugural president.

Sprigg was born in 1835 on his father's farm in Hampshire County, Virginia (present-day West Virginia). He was a descendant of English pioneer Thomas Cresap, a nephew of Maryland lawyer John Van Lear McMahon, and U.S. House Representatives James Sprigg, Michael Sprigg, and Clement Vallandigham. He studied jurisprudence in Baltimore and was admitted to the Maryland bar in 1858. Following a hiatus during the American Civil War, Sprigg relocated to Moorefield, West Virginia, in 1866 and established a law partnership with former judge J. W. F. Allen. That year, Sprigg was instrumental in organizing the Democratic Party of West Virginia.

In 1870, he was selected as the party's nominee for Attorney General of West Virginia, won election to the post and served from 1871 until 1872. During his term as attorney general, Sprigg decided that the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway Company was subject to taxation by the state; the case was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, which sustained Sprigg's decision. In 1886, Sprigg organized the West Virginia Bar Association; after being elected the inaugural president, he delivered the opening address at the organization's first meeting. Sprigg was elected to several terms as mayor of Moorefield and was afterward elected to a seat in West Virginia House of Delegates in 1888 representing the Second Delegate District, which consisted of Grant and Hardy counties. Following the disputed 1888 gubernatorial election between Aretas B. Fleming and Nathan Goff, Jr., Sprigg was appointed in 1889 as secretary of a joint committee of the West Virginia Legislature charged with investigating and deciding the results of the election.

Sprigg relocated to Cumberland in 1890. He was one of three incorporators of the Allegany County Bar Association, and in 1899 he was elected by the association as one of its directors. He unsuccessfully ran for a seat on the Cumberland city council in 1905 and a seat in the Maryland House of Delegates in 1907. In response to pollution of the North Branch Potomac River, Sprigg became chairman of the Pure Water League and waged a successful campaign to require the West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company to abandon the sulfite process of pulping in favor of a cleaner soda pulping method. While chairman of the Allegany County Democratic Convention in 1907, a resolution supporting an eight-hour workday was formally adopted by the convention. In 1908, he was appointed city attorney for Cumberland. Following a prolonged illness, he died in 1911.

Early life and family

Joseph Sprigg was born at "Swan Ponds" in Hampshire County, Virginia (present-day West Virginia), in October 1835. He was the son of Joseph Sprigg and Jane Duncan McMahon Sprigg.[1][2][3] Sprigg's father was a paternal descendant of the prominent Sprigg political family of Maryland and a maternal descendant of the Cresap family, which descended from English pioneer Thomas Cresap. Through his mother, Sprigg was a descendant of William McMahon, an early resident of Cumberland.[2] Three of his uncles were U.S. House Representatives: James Sprigg of Kentucky and Michael Sprigg of Maryland (brothers of his father) and Clement Vallandigham of Ohio, who was married to his aunt Louisa Anna McMahon Vallandigham.[2][4] His maternal grandmother was a member of the Van Lear family of Maryland.[2] In addition, Sprigg's sister Mary "Mollie" R. Sprigg McMahon was the wife of U.S. House Representative John A. McMahon.[5][6][7] Sprigg had seven siblings, six brothers and one sister:[5] Richard M. Sprigg, Howard Sprigg, Randolph Sprigg, James Sprigg, Mary "Mollie" R. Sprigg McMahon, John M. Sprigg,[8][9] and Van Lear (or Vanlear) Sprigg.[10]

Sprigg was raised on his father's "Swan Ponds" farm in Hampshire County, where his father provided a private tutor for his son's primary education.[2] His father owned farms on both sides of the North Branch Potomac River in Hampshire County, Virginia, and Allegany County, Maryland. On March 7, 1844, the Maryland General Assembly passed an act authorizing Sprigg's father to freely move his slaves across state lines between his farms as often as he deemed necessary.[11] His father relocated the family from the Hampshire County farm to Cumberland in 1852. Sprigg continued his education in Cumberland, and, following the completion of his studies there, he moved to Baltimore to study jurisprudence under his uncle John Van Lear McMahon.[2] He studied under his uncle until 1858, when he was admitted to the Maryland bar.[2][3] Sprigg's practice of law underwent a hiatus during the American Civil War.[2] He was a proponent of states' rights and sympathized with the cause of the Confederate States of America during the war; however, he did not take up arms during the conflict.[12] During the war, his father died in Cumberland in 1864.[2]

Law and political careers

West Virginia

In April 1866, Sprigg relocated to Moorefield in the Potomac Highlands of West Virginia and established a law partnership with former judge J. W. F. Allen.[1][2][3] Due to West Virginia's disenfranchisement of Confederate sympathizers and belligerents, Allen was unable to practice law, and Sprigg initially carried the burden of arguing the practice's cases.[12] The law firm was immediately successful, and Sprigg continued the practice of law in Hardy County for over 23 years, during which time he argued in every important civil and criminal case held in that county court.[2] In addition to Hardy County, Sprigg and Allen were also members of the Hampshire County bar.[13]

Also in 1866, Sprigg was instrumental in organizing the Democratic Party of West Virginia, after which time he continued to serve as a leader at the party's state and regional conventions.[2] He attended the Democratic Party's state convention held in Charleston in June 1870, where he represented the Tenth Senatorial District on the Committee on Resolutions.[14][15] Sprigg was unanimously nominated as the party's candidate for Attorney General of West Virginia, initially without his knowledge.[1][14][15] He commenced his campaign for attorney general at the state party's Tenth Senatorial District convention in Moorefield.[16] Sprigg ran against incumbent Aquilla B. Caldwell and was subsequently elected to the post with 28,020 votes, a large majority, and began his term as attorney general on January 1, 1871.[1][17][18] Sprigg was the first Democrat to serve as Attorney General of West Virginia.[19][20] On February 2, 1871, the West Virginia Legislature passed an act that extended Sprigg's time to qualify for his office until March 5 of that year.[21]

During his term as attorney general, Sprigg decided that the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway Company was subject to taxation by the state. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, which sustained his decision. During the contentious Democratic gubernatorial nomination contest between Johnson N. Camden and John Jeremiah Jacob in 1872, Sprigg lent his support to Camden. Camden received the party's nomination, but despite the support from Sprigg, he lost in the general election to Jacob, who ran as a "People's Independent" candidate.[2] Sprigg served as the attorney general until his term's end on December 31, 1872.[2][17] Despite expectations that he would seek reelection to the post, he withdrew his candidacy at the Democratic Party's state convention in 1872.[12][22][23] He was, however, chosen as one of the party's electors at large.[22]

Sprigg attended the Democratic Party's state convention at Charleston in June 1876 and represented the Eleventh Senatorial District on the committee on resolutions.[24] Prior to the general election of 1876, Sprigg delivered speeches at a number of public speaking engagements hosted by county Democratic committees, including an event in Charles Town where he headlined alongside U.S. Senator Henry G. Davis on October 24.[25]

At West Virginia's 2nd congressional district Democratic convention in July 1884, Sprigg was chairman of the district and nominated its executive committee.[26]

In 1886, Sprigg organized and was elected as the inaugural president of the West Virginia Bar Association and delivered the opening address at the organization's first meeting.[3][27][28] Sprigg served as president of the bar association until 1887, and again delivered the opening address at the association's annual meeting that year.[28]

Even though he did not pursue or seek out elected office, Sprigg was repeatedly called upon to run for office by the West Virginia Democratic Party.[2] After his term as attorney general, he was elected to several terms as mayor of Moorefield.[2] In 1888, despite his protest before the Democratic Party state convention, he was nominated to run for a seat in West Virginia House of Delegates representing the Second Delegate District, which consisted of Grant and Hardy counties.[1][29][30] He was elected following a highly contested campaign and served for the 1889 legislative session.[4][29] During his tenure, Sprigg served as chairman of the Judiciary Committee and was initially a candidate for Speaker of the West Virginia House of Delegates.[31][32] Also in 1888, Sprigg was selected as part of West Virginia's attending delegation to the inauguration of President Benjamin Harrison.[33][34] To resolve the disputed results of the 1888 gubernatorial election between Aretas B. Fleming and Nathan Goff, Jr., Sprigg was appointed in April 1889 as secretary of a joint committee of the West Virginia Legislature charged with investigating and deciding the results of the election.[3][35] While serving on the committee, he was a dominant spokesman for the Democratic side in support of Fleming, who was ultimately chosen as the winner of the election.[36][37]

Maryland

In 1890, after the close of the legislative year, Sprigg relocated from Moorefield to Cumberland, Maryland.[1] He resumed the practice of law and by 1894, his law office was located in the George's Creek and Cumberland Railroad headquarters building on Washington Street in Cumberland.[38][39] Following the 1898 decisive victory of Winfield Scott Schley, a Frederick native, at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba during the Spanish–American War, Sprigg led an initiative in 1899 to raise funds for a silver service to be awarded from the people of Maryland to Schley in recognition of his actions.[40]

Sprigg was one of three incorporators of the Allegany County Bar Association, and in 1899 he was elected by the association as one of its directors.[41][42]

Sprigg also became active in the Pure Water League, of which he served as chairman. The league was formed in December 1899 for the purpose of cleaning up the pollution of the North Branch Potomac River, Cumberland's main public water source. West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company which was blamed for the majority of the river's pollution.[43][44][45] Other cities downstream from the company's Luke pulp mill, including Hancock, complained of pollution and decreased fish populations in the river.[46] The league enlisted U.S. Senator George L. Wellington and U.S. House Representative George Alexander Pearre in seeking congressional support for the river's cleanup.[44][45][46] The following year, the West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company came to an agreement with the city of Cumberland, promising to abandon its process of using a sulfite process for producing pulp in favor of soda pulping. In exchange, the league and the city of Cumberland abandoned their pending court cases against the company.[47] To celebrate the league's progress toward meeting its goal, it held a "Jubilee Concert" on August 27, 1900, at Cumberland's Riverside Park.[43]

In 1905, he was a candidate for the Ward No. 1 seat on the Cumberland city council in the Democratic primary, and lost.[48][49] Sprigg also attended the annual meeting of the West Virginia Bar Association in December 1905, where he delivered an address to mark the twentieth anniversary of the association's establishment.[50][51] In reporting on his address, The Fairmont West Virginian newspaper named Sprigg the "Father of the West Virginia Bar".[51]

Sprigg continued to be active in Cumberland city politics. In early 1906, Sprigg was a spokesperson for the Associated Merchants organization, which had hired an independent auditor to investigate the city government's questionable accounting and appropriation practices. The independent auditor uncovered gross mismanagement, and the Associated Merchants, with Sprigg as their spokesperson, urged the Cumberland city council to take action.[52]

By 1907, Sprigg was one of the oldest active members of the Allegany County bar.[1] While chairman of the Allegany County Democratic Convention in August 1907, a resolution supporting an eight-hour workday was formally adopted by the convention.[53] Also that year, Sprigg received his party's nomination and unsuccessfully ran for election to the Maryland House of Delegates.[3][54][55] In September 1908, Sprigg gave an introductory speech for William Jennings Bryan, who visited Cumberland on his Chautauqua circuit.[56] In May 1908, the Cumberland city council appointed Sprigg as the city attorney, in which post he served during the mayoral administration of George A. Kean.[3][57][58]

Business pursuits

While residing in West Virginia, Sprigg was an incorporator of several companies aimed at bringing further economic development to Moorefield and the South Branch Potomac River Valley. In February 1869, Sprigg became an incorporator of the Moorefield Building Co-operative Association, which managed a fund for investment in real estate development and construction.[59] In March 1869, he was an incorporator of the Cumberland, Moorefield and Broadway Rail Road Company, which was established to undertake the construction and maintenance of a proposed railway from a point on the North Branch Potomac River in Mineral County to the Virginia–West Virginia state line near Monterey. The railway was meant to connect Cumberland with Moorefield and Petersburg in West Virginia and Monterey in Virginia. The company had also sought to build and maintain a branch line from Moorefield to Broadway in Virginia. The company was headquartered in Moorefield, the town of Sprigg's then-residence.[60] Also in March 1869, he was named as an incorporator of a second railroad company, the Moorefield and South Branch Valley Railroad Company. This proposed railway was to be built from a point on the Potomac River west of Harpers Ferry to a point on the Ohio River south of Parkersburg with part of its route traversing the South Branch Potomac River Valley.[61] Neither of these two railroads were ever constructed as originally proposed.

Later life and death

Sprigg was a member and sometime president of the Tri-State Agricultural Association of Allegany County, which held a fair at its grounds near Cumberland in October 1894 and 1895.[39][62][63]

Sprigg was an active Freemason, and served as junior warden and later master of the Potomac Lodge, Number 100 of the Free and Accepted Masons, in Cumberland.[3][64][65] He was also a charter member of Cumberland's McKinley Chapter 12 of the Order of the Eastern Star.[3][66][67] In 1905, Sprigg was elected as grand Adah of the order's Grand Maryland Chapter during the chapter's state convention in Cumberland; and that same year, he served as grand chaplain general of the McKinley Chapter.[66][68] Sprigg was a member of the Episcopal Church and attended Emmanuel Episcopal Church in Cumberland, where he served as vice president and president of the Emmanuel Episcopal Church Club.[69][70]

As a former Confederate sympathizer during the American Civil War, Sprigg was active in Confederate memorial activities. In 1902, he delivered a speech on behalf of Confederate veterans at Memorial Day exercises in Cumberland.[71][72][73]

Following a prolonged illness, Sprigg died at his residence on Washington Street in Cumberland on November 3, 1911. He was survived by his wife Mary Ellen and their four daughters.[3][74] Sprigg's funeral service was held on November 6 at Emmanuel Episcopal Church in Cumberland.[3] He was interred at Rose Hill Cemetery.[3][74]

Marriage and children

Sprigg was married in February 1867 to Mary Ellen Stubblefield, daughter of Dr. George Stubblefield of Cumberland.[1][5][31] He and his wife had four daughters:[3][31][74]

- Ellen "Nellie" Bell Sprigg (February 1, 1868 – January 11, 1936)[74][75][76]

- Jane Duncan Sprigg Beall (1871 – December 21, 1946), married to Lawrence Lincoln Beall[74][77][78]

- Ada Beckham Griffith Sprigg, married Joel Llewellyn Griffith of Cumberland[74][79]

- Mary McMahon Sprigg (March 4, 1876 – November 13, 1969)[74][76][80]

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ Sprigg was sometimes erroneously referred to as "Spriggs.

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h "True Men For the House of Delegates". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. October 31, 1907. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Atkinson & Gibbens 1890, p. 363.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Death of Joseph Sprigg: Former Attorney General of West Virginia Passes Away". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. November 4, 1911. p. 9. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Atkinson & Gibbens 1890, pp. 363–364.

- ^ a b c Doliante 1991, p. 934.

- ^ Reed, Randall & Greve 1897, p. 313.

- ^ "News of the State: Events of Interest Here and There Yesterday and Today". The News. Frederick, Maryland. February 7, 1906. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "John M. Sprigg Dies in Ohio: A Gallant Confederate Soldier in Civil War". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. January 26, 1907. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Death of John M. Sprigg". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. January 27, 1907. p. 12. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Vanlear Sprigg". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. December 27, 1910. p. 11. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ Maryland General Assembly 1843, pp. 301–302.

- ^ a b c "The State Convention". Spirit of Jefferson. Charles Town, West Virginia. May 7, 1872. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ Maxwell & Swisher 1897, p. 497.

- ^ a b "The State Convention: Full Proceedings". The Democrat. Weston, West Virginia. June 20, 1870. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Democratic Convention: Appearance of Charleston". The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. Wheeling, West Virginia. June 11, 1870. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Campaign Opened". Spirit of Jefferson. Charles Town, West Virginia. August 2, 1870. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Atkinson & Gibbens 1890, p. 38.

- ^ "By the Governor of West Virginia: A Proclamation". The Weekly Register. Point Pleasant, West Virginia. January 5, 1871. p. 7. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ Office of the West Virginia Attorney General 1918, p. 3.

- ^ West Virginia Legislature 2011, p. 328.

- ^ West Virginia Legislature 1871, p. 90.

- ^ a b "Parkersburg Democratic Convention: Nomination of Officers". The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. Wheeling, West Virginia. May 31, 1872. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 8, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Democratic State Convention: Full Proceedings". The Democrat. Weston, West Virginia. June 10, 1872. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Charleston Convention: Stormy Times Over the Capital and Financial Question". The Weekly Register. Point Pleasant, West Virginia. June 15, 1876. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Public Speaking". Spirit of Jefferson. Charles Town, West Virginia. October 24, 1876. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Second District Congressional Democratic Convention". Spirit of Jefferson. Charles Town, West Virginia. July 29, 1884. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ West Virginia Bar Association 1886, p. 16.

- ^ a b West Virginia Bar Association 1909, p. 167.

- ^ a b Atkinson & Gibbens 1890, p. 98.

- ^ West Virginia Legislature 1917, p. 362.

- ^ a b c Atkinson & Gibbens 1890, p. 364.

- ^ "Various Items". Spirit of Jefferson. Charles Town, West Virginia. December 4, 1888. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Washington's Inauguration". Pittsburgh Daily Post. Pittsburgh. December 15, 1888. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Big Parade: And All the Other Features of the Celebration". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn. April 23, 1889. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "To Name The Governor: A Legislative Committee Investigating the West Virginia Gubernatorial Election". Pittsburgh Dispatch. Pittsburgh. April 25, 1889. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The West Virginia Gubernatorial Election Contest 1888–1890: Part I". West Virginia Archives and History. West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on February 8, 2001. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The West Virginia Gubernatorial Election Contest 1888–1890: Part II". West Virginia Archives and History. West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Joseph Sprigg, Attorney at Law". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. July 27, 1894. p. 22. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Tri-State Association". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. February 14, 1894. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Silver Service for Schley: Maryland's Gift to the Popular Victor of Santiago". The Evening Times. Washington, D.C. April 4, 1899. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Proceedings to Disbar Mr. Dick: Bar Association Files Serious Charges". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. May 11, 1907. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Bar Association Officers". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. December 26, 1899. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Cumberland Rejoices". The News. Frederick, Maryland. August 23, 1900. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Cumberland Citizens Aroused: League Formed to Continue Fight on Pollution of River". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. December 29, 1899. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Fight For Pure Water: Cumberland Citizens Hopeful of Getting Aid From Congress". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. January 6, 1900. p. 9. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Want Better Water: Citizens of Cumberland Protest Against Pollution of Potomac". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. January 2, 1900. p. 11. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "River Water Pollution to Cease". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. July 28, 1900. p. 10. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Democratic Primaries". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. April 25, 1905. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Democratic Candidates". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. April 26, 1905. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Second Day's Session of Bar Association Shows Large Increase in Attendance: Elkins is Selected as Next Place of Meeting". The Fairmont West Virginian. Fairmont, West Virginia. December 29, 1905. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Address of Hon. Joseph Sprigg, of Cumberland Before the W. Va. State Bar Association". The Fairmont West Virginian. Fairmont, West Virginia. December 29, 1905. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Merchants Before Council". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. January 4, 1906. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Convention in Cumberland Declares for an Eight hour Day". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. August 2, 1907. p. 5. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Result of the Great Battle: The Vote Each Candidate Received Yesterday". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. November 7, 1907. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Democratic County Ticket". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. October 1, 1907. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Cumberland Extends Welcome to the Great and Peerless One". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. September 12, 1908. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Was Known Here: Dr. Binkley Was Related by Marriage to Gen. and Mrs. Sprigg". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. June 5, 1909. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Looking Backward: 50 Years Ago, May 29, 1908". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. May 29, 1958. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ West Virginia Legislature 1870, p. 171.

- ^ West Virginia Legislature 1869, pp. 66–70.

- ^ West Virginia Legislature 1869, pp. 99–100.

- ^ "The Second Annual Fair and Races of the Tri-State Agricultural Association of Allegany County, Maryland". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. September 26, 1895. p. 12. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Tri-State Assn. Elects Officers". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. February 17, 1894. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Masons Meet at Joint Banquet: Potomac and Ohr Lodges Enjoy Pleasant Evening". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. May 2, 1908. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Have Elected Officers". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. December 21, 1899. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Eastern Star Session Closed: Grand Officers Elected at the Meeting Yesterday Afternoon". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. January 27, 1905. p. 8. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "McKinley Chapter, OES Will Observe 50th Anniversary". Cumberland Sunday Times. Cumberland, Maryland. October 14, 1951. p. 9. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "A Masonic Function: McKinley Chapter, Order Eastern Star Entertained Officers". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. June 23, 1905. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Notice". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. March 26, 1909. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Church Officers: An Interesting Meeting on Part of the Church Club". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. January 31, 1908. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Day Elsewhere: It Was More Generally Observed in City of Washington Than for Many Years". Altoona Tribune. Altoona, Pennsylvania. May 31, 1902. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Day in Cumberland: Union and Confederate Veterans Unite in Observing". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. Williamsport, Pennsylvania. May 31, 1902. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Blue and Gray Unite: Reunion of Former Foes at Decoration Day Exercises in Cumberland". The New York Times. New York City. May 31, 1902. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Prominent Lawyer Dies: Former Attorney General for West Virginia Succumbs at Cumberland". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. November 4, 1911. p. 5. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Birth Record Detail: Ellen Bell Sprigg". West Virginia Vital Research Records. West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Miss Ellen Sprigg". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. January 13, 1936. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Obituary: Lawrence Lincoln Beall". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. March 23, 1932. p. 9. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Mrs. Jane Beall". Cumberland Evening Times. Cumberland, Maryland. December 23, 1946. p. 13. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Griffith–Sprigg". The News. Frederick, Maryland. November 13, 1913. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Birth Record Detail: Mary McMahon Sprigg". West Virginia Vital Research Records. West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

Bibliography

- Atkinson, George Wesley; Gibbens, Alvaro Franklin (1890). Prominent Men of West Virginia: Biographical Sketches of Representative Men in Every Honorable Vocation, Including Politics, the Law, Theology, Medicine, Education, Finance, Journalism, Trade, Commerce and Agriculture. Wheeling, West Virginia: W. L. Callin. OCLC 3886825.

- Doliante, Sharon J. (1991). Maryland and Virginia Colonials. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8063-1293-4. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015.

- Maryland General Assembly (1843). Laws Made and Passed by the General Assembly of the State of Maryland. Annapolis, Maryland: William McNeir, Printer. OCLC 367597593. Archived from the original on November 6, 2015.

- Maxwell, Hu; Swisher, Howard Llewellyn (1897). History of Hampshire County, West Virginia From Its Earliest Settlement to the Present. Morgantown, West Virginia: A. Brown Boughner, Printer. OCLC 680931891. OL 23304577M.

- Office of the West Virginia Attorney General (1918). Twenty-Seventh Biennial Report and Official Opinions of the Attorney General of the State of West Virginia for the Fiscal Years Beginning July 1, 1916, and Ending June 30, 1918. Charleston, West Virginia: Tribune Printing Company. OCLC 506500089. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015.

- Reed, George Irving; Randall, Emilius Oviatt; Greve, Charles Theodore (1897). Bench and Bar of Ohio: A Compendium of History and Biography. Chicago: The Century Publishing and Engraving Company. OCLC 60713589.

- West Virginia Bar Association (1886). Constitution and By-Laws of the West Virginia Bar Association, Organized July 8, 1886, Together with the Opening Address of Hon. Joseph Sprigg and the Proceedings of the First Meeting. Morgantown, West Virginia: New Dominion Steam Printing House. OCLC 11874206. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015.

- West Virginia Bar Association (1909). Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth Annual Meeting of the West Virginia Bar Association Held at Huntington, West Virginia December 29–30, 1908. Morgantown, West Virginia: Acme Publishing Company. OCLC 11874180. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015.

- West Virginia Legislature (1869). Acts of the Legislature of West Virginia; At Its Session Commencing January 19, 1869. Wheeling, West Virginia: John Frew, Public Printer. OCLC 422695120. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015.

- West Virginia Legislature (1870). Acts of the Legislature of West Virginia; At Its Session Commencing January 18, 1870. Wheeling, West Virginia: John Frew, Public Printer. OCLC 422695120. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015.

- West Virginia Legislature (1871). Acts of the Legislature of West Virginia; At Its Ninth Session. Commencing January 17th, 1871. Charleston, West Virginia: H. S. Walker, Public Printer. OCLC 422695120. Archived from the original on November 28, 2015.

- West Virginia Legislature (1917). West Virginia Legislative Hand-Book and Manual and Official Register. Charleston, West Virginia: Tribune Printing Company. OCLC 9771361. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016.

- West Virginia Legislature (2011). Darrell E. Holmes, Clerk of the West Virginia Senate (ed.). "West Virginia Blue Book, 2011". West Virginia Blue Book. Charleston, West Virginia: Chapman Printing. ISSN 0364-7323. OCLC 1251675.

External links

Media related to Joseph Sprigg (attorney general) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Joseph Sprigg (attorney general) at Wikimedia Commons

- 1835 births

- 1911 deaths

- 19th-century American Episcopalians

- 19th-century American lawyers

- 19th-century American legislators

- 19th-century West Virginia politicians

- 20th-century American Episcopalians

- 20th-century American lawyers

- 20th-century Maryland politicians

- American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law

- American people of English descent

- Burials at Rose Hill Cemetery (Cumberland, Maryland)

- Maryland city attorneys

- Episcopalians from Maryland

- Episcopalians from West Virginia

- Lawyers from Cumberland, Maryland

- Maryland Democrats

- Maryland lawyers

- Mayors of places in West Virginia

- Members of the West Virginia House of Delegates

- People from Hampshire County, West Virginia

- People from Moorefield, West Virginia

- Politicians from Cumberland, Maryland

- Sprigg family

- West Virginia Attorneys General

- West Virginia Democrats

- West Virginia lawyers