Salzburg Festival

| Salzburg Festival Salzburger Festspiele | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre |

|

| Begins | late July |

| Ends | end of August |

| Frequency | annual |

| Location(s) | Salzburg, Austria |

| Inaugurated | 1920 |

| People | |

| Website | www |

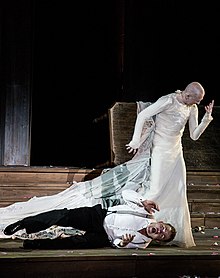

The Salzburg Festival (German: Salzburger Festspiele) is a prominent festival of music and drama established in 1920. It is held each summer, for five weeks starting in late July, in Salzburg, Austria, the birthplace of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart's operas are a focus of the festival; one highlight is the annual performance of Hofmannsthal's play Jedermann (Everyman).

Since 1967, an annual Salzburg Easter Festival has also been held, organized by a separate organization.

History

Music festivals were held in Salzburg at irregular intervals since 1877 by the International Mozarteum Foundation but were discontinued in 1910. A festival was planned for 1914, but it was cancelled at the outbreak of World War I. In 1917, Friedrich Gehmacher and Heinrich Damisch formed an organization known as the Salzburger Festspielhaus-Gemeinde to establish an annual festival of drama and music, emphasizing especially the works of Mozart.[1] At the close of the war in 1918, the festival's revival was championed by five men now regarded as its founders:[2] the poet and dramatist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, the composer Richard Strauss, the scenic designer Alfred Roller, the conductor Franz Schalk, and the director Max Reinhardt, then intendant of the Deutsches Theater in Berlin, who had produced the first performance of Hofmannsthal's play Jedermann at the Berlin Zirkus Schumann arena in 1911.

According to Hofmannsthal's political writings, the Salzburg Festival, as a counterpart to the Prussian-North German uncompromising worldview, should emphasize the centuries-old Habsburg principles of "live and let live" with regard to ethnic groups, peoples, minorities, religions, cultures and languages.[3][4][5] The Salzburg Festival was officially inaugurated on 22 August 1920 with Reinhardt's performance of Hofmannsthal's Jedermann on the steps of Salzburg Cathedral, starring Alexander Moissi. The practice has become a tradition, and the play is now always performed at Cathedral Square; since 1921 it has been accompanied by several performances of chamber music and orchestral works. The first operatic production came in 1922, with Mozart's Don Giovanni conducted by Richard Strauss. The singers were mainly drawn from the Wiener Staatsoper, including Richard Tauber in the part of Don Ottavio.

The first festival hall was erected in 1925 at the former Archbishops' horse stables on the northern foot of the Mönchsberg mountain, on the basis of plans by Clemens Holzmeister; it opened with Gozzi's Turandot dramatized by Karl Vollmöller. At that time the festival had already developed a large-scale program including live broadcasts by the Austrian RAVAG radio network. The following year the adjacent former episcopal Felsenreitschule riding academy, carved into the Mönchsberg rock face, was converted into a theater, inaugurated with a performance of The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni. In the 21st century, the original festival hall, suitable only for concerts, was reconstructed as a third venue for fully staged opera and concert performances and reopened in 2006 as the Haus für Mozart (House for Mozart).

During the years from 1934 to 1937, famed conductors such as Arturo Toscanini and Bruno Walter conducted many performances. In 1936, the festival featured a performance by the Trapp Family Singers, whose story was later depicted in the musical The Sound of Music (featuring a scene of the Trapp Family singing at the Felsenreitschule, but inaccurately set in 1938). In 1937, Boyd Neel and his orchestra premiered Benjamin Britten's Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge at the festival.[6]

The festival's popularity suffered a major blow as a consequence of the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938. Toscanini resigned in protest, artists of Jewish descent like Reinhardt and Georg Solti had to emigrate, and Jedermann, last performed by Attila Hörbiger, had to be dropped. Nevertheless, the festival remained in operation until in 1944 it was cancelled by the order of Reich Minister Joseph Goebbels in reaction to the 20 July plot. At the end of World War II, the Salzburg Festival reopened in summer 1945 immediately after the Allied victory in Europe.

Post World War II festivals

The post-war festival slowly regained its prominence as a summer opera festival, especially for works by Mozart, with conductor Herbert von Karajan becoming artistic director in 1956. In 1960 the Great Festival Hall (Großes Festspielhaus) opera house opened its doors. As this summer festival gained fame and stature as a venue for opera, drama, and classical concert presentation, its musical repertoire concentrated on Mozart and Strauss, but other works, such as Verdi's Falstaff and Beethoven's Fidelio, were also performed.

Upon Karajan's death in 1989, the festival was drastically modernized and expanded by director Gerard Mortier, who was succeeded by Peter Ruzicka in 2001.

21st century

In 2006, the festival was led by intendant Jürgen Flimm and concert director Markus Hinterhäuser. That year, Salzburg celebrated the 250th anniversary of Mozart's birth by staging all 22 of his operatic works, including two unfinished operas.[7] All 22 were filmed and released on DVD in November 2006. The 2006 festival also saw the opening of the Haus für Mozart.

In 2010, the opera Dionysos by Wolfgang Rihm who compiled for his own libretto texts from Nietzsche's Dionysian-Dithyrambs premiered. Alexander Pereira succeeded Flimm as intendant, who departed in 2011 to become director of the Berlin State Opera. Pereira's objective for the festival was to present only new productions.[8] When he resigned at the end of the 2014 festival season to take over as the General Director of La Scala, Sven-Eric Bechtolf, who had served as Drama Director of the Salzburg Festival since 2012, took over as Interim General Manager. The 2015 festival marked the first one for which Bechtolf was responsible for the artistic programming. Budget cuts led to a retreat from Pereira's "new productions only" objective.[9] The 2015 opera program presented only three new productions—Le nozze di Figaro, directed by Bechtolf; Fidelio, directed by Claus Guth; and Wolfgang Rihm's rarely performed Die Eroberung von Mexico (The Conquest of Mexico), directed by Peter Konwitschny.[10] The remaining four opera productions—Norma, Il trovatore, Iphigénie en Tauride, and Der Rosenkavalier—were revivals. In 2018, Lydia Steier was the first woman to stage Die Zauberflöte.[11]

Markus Hinterhäuser became Intendant of the Festival in 2016.[12] In April 2024, the Festival announced an extension of Hinterhäuser's contract as Intendant through 2031.[13]

Economy

The Salzburg Festival reports in 2017 ticket sales revenue of about €27 million, and directly and indirectly creates value to the sum of €183 million in Salzburg per year. The festival thereby secures employment in Salzburg (including year-round employees and full-time equivalent adjusted seasonal workers of the festival) of 2800 full-time jobs (Austria 3400). Through their effect in other sectors, directly and indirectly they provide the public sector with approximately €77 million of taxes and duties.[14]

Salzburg Whitsun Festival

The Salzburg Whitsun Festival (Salzburger Pfingstfestspiele) was established at the behest of Herbert von Karajan in 1973 as a brief concert series with the name Pfingstkonzerte. Today its schedule remains, at four days, brief, but is characterized by multiple events each day; and it is managed under the umbrella of the main (summer) Salzburg Festival. (Pfingst is Whitsun in the U.K. and Pentecost in the U.S.; the British term is used by the festival's management.)

The first Whitsun Concerts centered on three symphonies by Bruckner, all conducted by Karajan and played at the Großes Festspielhaus over three days by the Berlin Philharmonic. Years later, opera became part of the activities, and "Concerts" became officially "Festival". In the 1990s there began an emphasis on works from the Baroque repertoire. In 2005, for example, the Salzburg Whitsun Festival presented Handel's Acis and Galatea and his oratorio Solomon.

In 2007, Riccardo Muti became the artistic director of the festival under a five-year contract during which he presented fully staged performances of operatic rarities from the 18th and 19th century Neapolitan School of opera in the Haus für Mozart. He has been succeeded by mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli, also for a period of five years.

Among a series of concerts and, for the first time in the history of the festival, dance performances (by the Kirov Ballet), Bartoli is to star in a full-staged opera each year, which will then be repeated at the Summer Festival in July and August. In 2012, she sang Cleopatra in Handel's Giulio Cesare, in 2013 the title role in Vincenzo Bellini's Norma, and in 2014 Rossini's La Cenerentola. In 2015 she performed the title role in Iphigénie en Tauride by Christoph Willibald Gluck, and in 2016 she sang Maria in Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story.[15]

See also

References

- ^ Eisen, Cliff; Keefe, Simon P., eds. (2006). The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-52185-659-1.

- ^ Lütteken, Laurenz [in German] (2014). Richard Strauss: Musik der Moderne (in German). Reclam. p. 138. ISBN 978-3-15-010973-1.

- ^ William M. Johnston "Zur Kulturgeschichte Österreichs und Ungarns 1890–1938." (2015), ISBN 978-3-205-79378-6, p. 46.

- ^ Thomas Thiel "Hugo von Hofmannsthal im Ersten Weltkrieg – Requiem auf eine zerbrechliche Idee", Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 18 April 2014.

- ^ Kurt Ifkovits in: "Hofmannsthal. Orte" (Hemecker/Heumann, 2014), p 336.

- ^ The Gramophone, June 1972, p. 178[author missing][title missing]

- ^ "Mozart 22". Der Tagesspiegel (Press release) (in German). Berlin. tso/Deutscher Depeschendienst (ddp). 18 July 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Gurewitsch, Matthew (May 2012). "New to Salzburg". Opera News. New York City. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ "Nach Pereira: Salzburger Festspiele auf Konsolidierungskurs" [After Pereira: Salzburger Festspiele on consolidation course] (in German). ORF. 8 July 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ "Opening of the Salzburg Festival". Deutsche Welle. 17 July 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Hanssen, Frederik (28 July 2018). "Die Zauberflöte in Salzburg / Im Königreich der Fastnacht". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Hinterhäuser bleibt Intendant der Salzburger Festspiele". NMZ. 5 April 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ "Markus Hinterhäuser Remains Artistic Director of the Salzburg Festival" (Press release). Salzburg Festival. 5 April 2024. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ "Report Salzburg Festival: Economic engine, excellence infusion for the location" (PDF). Wirtschaftskammer Salzburg. 28 June 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ Salzburg Whitsun Festival. Program detail: West Side Story. Retrieved 9 September 2015.