Hermann and Dorothea

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (May 2013) |

Hermann and Dorothea is an epic poem, an idyll, written by German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe between 1796 and 1797, and was to some extent suggested by Johann Heinrich Voss's Luise, an idyll in hexameters, which was first published in 1782–1784. Goethe's work is set around 1792 at the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars, when French forces under General Custine invaded and briefly occupied parts of the Palatinate. The hexameters of the nine cantos are at times irregular.

With the poem as his source, Robert Schumann composed an overture in B minor entitled Hermann and Dorothea, his Op. 136. The overture dates from 1851.

Summary

[edit]Hermann, son of the wealthy innkeeper in a small town near Mainz, is sent by his mother to bring clothes and food to the refugees which have set up camp near their town. They have fled their villages on the western side of the Rhine river, now occupied by the French Revolutionary Army, in order to seek refuge on the eastern side. On his way to the camp, Hermann meets Dorothea, a young maid who assists a woman in her childbed on her flight. Overwhelmed by her courage, compassion, and beauty, Hermann asks Dorothea to distribute his donations among her poor fellow refugees.

Back home, he reveals his affection to his parents. His father brushes away his timid confession, reminding him bluntly that he wants Hermann to choose a wife from a respected local family with a generous dowry. He goes on to express his deep disappointment with Hermann's perceived lack of ambition to move forward in life, and lectures him about how he should become a respected citizen.

After Hermann has left in despair, his mother utters the following timelessly wise and deeply moving verses:

- Immer bist du doch, Vater, so ungerecht gegen den Sohn! und So wird am wenigsten dir dein Wunsch des Guten erfüllet. Denn wir können die Kinder nach unserem Sinne nicht formen; So wie Gott sie uns gab, so muß man sie haben und lieben, Sie erziehen aufs beste und jeglichen lassen gewähren. Denn der eine hat die, die anderen andere Gaben; Jeder braucht sie, und jeder ist doch nur auf eigene Weise Gut und glücklich.

- Why will you always, father, do our son such injustice? That least of all is the way to bring your wish to fulfillment. We have no power to fashion our children as it suits our will; As they are given by God, so we must have them and love them; teach them as best we can, and let each of them follow his nature. One will have talents of one sort, and different talents another. Every one uses his own; in his own individual fashion, each must be happy and good.

Hermann's mother goes after her son and finally finds him in a far corner of their garden. Having been shaken to tears by his father's harsh words, Hermann tells his mother that he intends to marry Dorothea or else to stay bachelor for the rest of his life. His mother understands the sincerity and depth of his affections and decides to help him obtain his father's permission. They return to Hermann's father, who still discourses with his respected neighbors, the town's pharmacist and the young and wise parish priest. The two friends offer to collect inquiries among the refugees to find out if Dorothea is virtuous and worthy to be Hermann's bride. Moved by his wife's and friends' persuasion, Hermann's father grudgingly promises that he will abide by his two friends' recommendation.

Background and interpretation

[edit]The story of the well-settled burgher's son marrying a poor fugitive was contained in an account of the Salzburg Protestants who, for their religion, in 1731 fled from their old homes into Germany. The inhabitants and conditions of the little town which is the scene of Hermann and Dorothea are pictured in contrast to the turmoil of the French Revolution, for they stand for the foundations on which civilization will always rest. The leading characters represent the standard callings of men — the farmer, the merchant, the apothecary-doctor, the minister, the judge. The hero is the true son of mother earth, given to tilling the soil and harvesting his crops.

The life both in family and community is depicted as the fundamental social forms, with some hints of national life. The love story of the young couple is free from wild romance, indeed their love makes them look to the future not with any anticipation of pleasure or extravagance, but with the instinctive conviction that the true blessings of life flow from the performance of necessary tasks. The public spirit of Hermann's father germinates also in the son's character as his burning patriotism protests against the French invasion. But the spirit that permeates the poem as a whole is that of trust in the future and sympathy with mankind.

Ewald Eiserhardt, a reviewer for Encyclopedia Americana, cites the serene flow of presentation, the masterly descriptions of landscape and home, the plastic vigor of the main figures, the balance of color, all as rendering Hermann and Dorothea a great work of literary art.

Schumann's overture

[edit]| Hermann und Dorothea | |

|---|---|

| by Robert Schumann | |

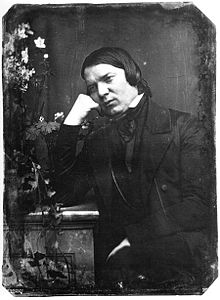

Robert Schumann in an 1850 daguerreotype | |

| Opus | 136 |

| Period | Romantic period |

| Genre | Overture |

| Based on | Goethe's Hermann und Dorothea |

| Composed | 1851 |

| Dedication | Clara Schumann |

| Scoring | piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, side drum, and strings |

Composition

[edit]Schumann composed his overture Hermann und Dorothea Op. 136 in the December of 1851. He had just completed revision of what would soon be published as his fourth symphony; he began work on the overture the same day as the completion of the symphony, a practice of which he had sometime expressed disapproval, but of which he was often guilty all the same.

In France, 1851 was the year of the coup d'état which brought Napoleon III to power; this event, just as well as the revolutionary violence in Germany, brought France, revolution and its difficult personal consequences to the front of Schumann's mind. Schumann himself had, as an infant in 1812, borne witness to the pressure placed upon the townsfolk of Zwickau when some 200,000 fighting men of the Grande Armée passed through on their way to eventual defeat in Russia; following the defeat many soldiers returned to Zwickau and other such central European towns in order to extract provisions from their inhabitants. This was the cause of considerable economic hardship, but also of more direct suffering from violence at the hands of a large body of foreign soldiers.

Originally Schumann had considered Hermann und Dorothea an apt text for adaptation into a libretto; his fourth symphony had at first been named for his wife Clara, and during work on the revision he was moved to express his devotion to her in a new composition. Hermann und Dorothea, with its themes of love against the odds, personal struggle, and familial opposition to marriage, was a natural subject; and Schumann saw in its strong-willed hero and idealised heroine neat ciphers for himself and Clara. Eventually Schumann decided against an opera; the fairly poor reception of his Genoveva, which had had its premiere the previous year, might have stayed his eagerness. The overture which he settled upon was completed in two days' work; it was dedicated to "Seiner lieben Clara".

Music

[edit]The overture is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets in A, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, side drum, and strings with contrabass. It is in common time, though Schumann uses triplets freely in many parts to suggest a time of twelve; it has B minor as its principal key. It is marked Mäßig and given a metronome tempo of ![]() = 126.

= 126.

There is some structural departure from the model which Beethoven provided in his overture from Egmont, itself incidental music for a play by Goethe, and in his Coriolan, also based upon a celebrated work of literature. Schumann does not use sonata form, as in the Egmont overture, and as in Schumann's Julius Caesar, composed at the beginning of the same year; nor does he crib directly from the structure of the poem which was his source, as in Coriolan. Instead the overture is dominated by thematic writing, and melodies introduced early on reoccur freely in many keys, often transformed by inversion, augmentation, fragmentation, recombination, or other devices.

The overture's principal theme, shown here, is alternated with extracts from the Marseillaise, and with a brighter second subject for contrast. The dour mood which the first theme evokes associates it by Hermann; the second theme's major key and lyricism associate it by Dorothea. The themes are combined throughout the work, and are developed later in the overture; in moments of urgency or great passion they are often joined together contrapuntally. The piece ends with a parallel-major coda in B.

The overture has been arranged several times for four hands, notably by August Horn.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ewald Eiserhardt (1920). . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

- Sams, Eric (1968). "Politics, Literature, People in Schumann's Op. 136". The Musical Times. 109: 25–7.

Further reading

[edit]- W. von Humboldt, Æsthetische Versuche: Hermann und Dorothea (1799)

- V. Hehn, Ueber Goethes Hermann und Dorothea (1893)

- Herman and Dorothea 1801 English translation by Thomas Holcroft on Google Books

Full text of Hermann and Dorothea from Project Gutenberg

- In the original [1].

- In a translation by Ellen Frothingham.

- In a Chinese translation version by Guo Moruo.

External links

[edit] Hermann und Dorothea public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Hermann und Dorothea public domain audiobook at LibriVox