Good-Bye to All That

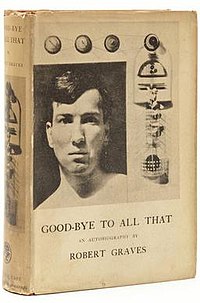

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Robert Graves |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 1929 1958 (2nd Edition) |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 368 (paperback) |

| ISBN | 0-385-09330-6 |

| OCLC | 21298973 |

| 821/.912 B 20 | |

| LC Class | PR6013.R35 Z5 1990 |

Good-Bye to All That is an autobiography by Robert Graves which first appeared in 1929, when the author was 34 years old. "It was my bitter leave-taking of England," he wrote in a prologue to the revised second edition of 1957, "where I had recently broken a good many conventions".[1] The title may also point to the passing of an old order following the cataclysm of the First World War; the supposed inadequacies of patriotism, the interest of some in atheism, feminism, socialism and pacifism, the changes to traditional married life, and not least the emergence of new styles of literary expression, are all treated in the work, bearing as they did directly on Graves's life. The unsentimental and frequently comic treatment of the banalities and intensities of the life of a British army officer in the First World War gave Graves fame,[1] notoriety and financial security,[1] but the book's subject is also his family history, childhood, schooling and, immediately following the war, early married life; all phases bearing witness to the "particular mode of living and thinking" that constitute a poetic sensibility.[1]

Laura Riding, Graves's lover, is credited with being a "spiritual and intellectual midwife" to the work.[2] Graves, in a 1969 interview, claimed that he "entirely rewrote" the book—"every single sentence"—when it was reissued in the 1950s, suggesting that the process of co-writing The Reader Over Your Shoulder had made him more conscious of, and determined to rectify, deficiencies in his own style.[3]

Pre-war life

[edit]Graves undertook climbing, stating "the sport made all others seem trivial." His first climb was Crib y Ddysgl, followed by climbs on Crib Goch and Y Lliwedd.[4]: 61–66

Graves goes on to claim, "In English preparatory and public schools romance is necessarily homosexual. The opposite sex is despised and treated as something obscene. Many boys never recover from this perversion. For every one born homosexual, at least ten permanent pseudo-homosexuals are made by the public school system: nine of these ten as honourably chaste and sentimental as I was."[4]: 19

Wartime experiences

[edit]A large part of the book is taken up by his experience of the First World War, in which Graves served as a lieutenant, then captain in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, with Siegfried Sassoon. Good-Bye to All That provides a detailed description of trench warfare, including the tragic incompetence of the Battle of Loos, including the use of gas, and the bitter fighting in the first phase of the Somme Offensive. At one point Graves agrees with his C.S.M., "Of course, it's murder, you bloody fool, And there's nothing else for it, is there?"[4]: 141–168, 205–226

Graves claimed, "At least one in three of my generation at school died; because they all took commissions as soon as they could, most of them in the infantry and Royal Flying Corps. The average life expectancy of an infantry subaltern on the Western Front was, at some stages of the War, only about three months; by which time he had been either wounded or killed."[4]: 59

Regarding trench conditions and Cuinchy-bred rats, Graves stated, "They came up from the canal, fed on the plentiful corpses, and multiplied exceedingly."[4]: 138

Wounds

[edit]In the Somme engagement, Graves was wounded while leading his men through the cemetery at Bazentin-le-petit church on 20 July 1916. The wound initially appeared so severe that military authorities erroneously reported to his family that he had died. While mourning his death, Graves's family received word from him that he was alive, and put an announcement to that effect in the newspapers. Graves later regretted omitting from the book the name of the soldier who had rescued him, Owen Roberts. The two met again fifty years later in a hospital ward to which both had been admitted for surgery, after which Graves signed Roberts's copy of the book, giving Roberts full credit for saving his life.[5]

Reputed atrocities

[edit]Graves also discussed atrocities committed during the war in Good-Bye to All That. He wrote that among his fellow troops, Allied atrocity propaganda, such as reports of the rape of Belgium, was widely disbelieved (defining "atrocities" in the book as wartime sexual violence, mutilation and torture instead of summary executions). Graves also noted that if "the atrocity-list had to include the accidental-on-purpose bombing or machine-gunning of civilians from the air, the Allies were now committing as many atrocities as the Germans." Observing French and Belgian civilians showing British soldiers body parts allegedly mutilated by German troops, he argued that these were more likely the result of indiscriminate shelling.[4]: 183–184

Though the German use of serrated knives and British deployment of expanding bullets were regarded by the other side as "atrocious", Graves claimed that the opportunity for soldiers on both sides to commit "true atrocities" only occurred when escorting prisoners of war to the rear lines. "Nearly every instructor in the mess", he wrote, "could quote specific instances of prisoners having been murdered on the way back. The commonest motives were, it seems, revenge for the death of friends or relatives, jealousy of the prisoner's trip to a comfortable prison camp in England, military enthusiasm, fear of being suddenly overpowered by the prisoners or, more simply, impatience with the escorting job." Similarly, "If a German patrol found a wounded man, they were likely as not to cut his throat." However, if POWs arrived at their destination, they were treated well during interrogations.[4]: 131, 183–184

In the book, Graves stated that Australian and Canadian troops had the worst reputation for atrocities against German POWs. He recounted two first-hand anecdotes from a Scottish-Canadian and an Australian, who told him how they murdered German prisoners while escorting them using Mills bombs. Canadian soldiers were motivated to commit atrocities against POWs due to the story of "The Crucified Soldier", which Graves and his fellow soldiers also refused to believe. He also added that the use of "semi-civilized coloured troops in Europe was, from the German point of view, we knew, one of the chief Allied atrocities. We sympathized."[4]: 184–185

Postwar trauma

[edit]Graves was severely traumatised by his war experience. After being wounded in the lung by a shell blast, he endured a squalid five-day train journey with unchanged bandages. During initial military training in England, he received an electric shock from a telephone that had been hit by lightning, which caused him for the next twelve years to stammer and sweat badly if he had to use one. Upon his return home, he describes being haunted by ghosts and nightmares.[6]

According to Graves, "My particular disability was neurasthenia." He went on to say, "Shells used to come bursting on my bed at midnight ... strangers in daytime would assume the faces of friends who had been killed." Offered a chance to rejoin George Mallory in climbing, Graves declined, "I could never again now deliberately take chances with my life."[4]

Critical responses

[edit]Siegfried Sassoon and his friend Edmund Blunden (whose First World War service had been in a different regiment) took umbrage at the contents of the book. Sassoon's complaints mostly related to Graves's depiction of him and his family, whereas Blunden had read the memoirs of J. C. Dunn and found them at odds with Graves in some places.[7] The two men took Blunden's copy of Good-Bye to All That and made marginal notes contradicting some of the text. That copy survives and is held by the New York Public Library.[8] Graves's father, Alfred Perceval Graves, also incensed at some aspects of Graves's book, wrote a riposte to it titled To Return to All That.[9]

It was included in Robert McCrum's Guide to the 100 greatest nonfiction books in English published by The Guardian.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Robert Graves (1960). Good-Bye to All That. London: Penguin. p. 7.

- ^ Richard Perceval Graves, 'Graves, Robert von Ranke (1895–1985)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, October 2006.

- ^ "The Art of Poetry XI: Robert Graves," in Conversations with Robert Graves, ed. Frank L. Kersnowski (1989), University Press of Mississippi, p. 101.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Graves, Robert (1985). Good-Bye To All That. Vintage International Edition. pp. 249, 267–268, 272, 287, 289, 296, 314. ISBN 9780385093309.

- ^ Good-bye to All That, by Roger Ebert, 4 December 1966 (published online on 22 December 2010

- ^ "The Other: For Good and For Ill"[permanent dead link] by Prof. Frank Kersnowski in Trickster's Way, Volume 2, Issue 2, 2003

- ^ "Hugh Cecil, "Edmund Blunden and First World War Writing 1919–36"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Anne Garner, "Engaging the Text: Literary Marginalia in the Berg Collection", June 4, 2010. Accessed 6 November 2012.

- ^ Graves, A. P. (1930). To return to all that: an autobiography. J. Cape. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ^ McCrum, Robert (28 November 2016). "The 100 best nonfiction books: No 44 – Goodbye to All That by Robert Graves (1929)". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 November 2023.