Snake scale

Scales are important for snakes - they are deemed to be reptiles by the presence of scales, amongst other things.[1] Snakes are entirely covered with scales or scutes of various shapes and sizes. Scales protect the body of the snake, allow moisture to be retained within and give simple or complex colouration patterns which help in camouflage and anti-predator display.

Scales have been modified over time to serve other functions such as 'eyelash' fringes, and protective covers for the eyes[2] with the most distinctive modification being the rattle of the North American rattlesnakes.

Snakes periodically moult their scaly skins and acquire new ones. This permits replacement of old worn out skin, disposal of parasites and is thought to allow the snake to grow. The arrangement of scales is used to identify snake species.

Snakes have been part and parcel of culture and religion. Vivid scale patterns have been thought to have influenced early art. The use of snake-skin in manufacture of purses, apparel and other articles led to large-scale killing of snakes, giving rise to advocacy for use of artificial snake-skin. Snake scales are also to be found as motifs in fiction, video games and films.

Functions of scales

The dorsal (or back) scales of a snake protect it from damage due to friction as it moves.[3] The ventral (or belly) scales, which are large and oblong, protect the soft underside of the snake and also grip surfaces allowing the snake to move. The large scales (called 'shields') on the snake's head play a similar role.[4]

Snake skin and scales help retain moisture in the animal's body.[5]

Snakes pick up vibrations from both the air and the ground, and can differentiate the two, using a complex system of internal resonances (perhaps involving the scales) [1].

Morphology of scales

Snake scales are formed by the differentiation of the snake's underlying skin or epidermis.[2] Each scale has an outer surface and an inner surface. The skin from the inner surface hinges back and forms a free area which overlaps the base of the next scale which emerges below this scale.[6]

A snake is born with a fixed number of scales. The scales do not increase in number as the snake matures nor are do they reduce in number over time. The scales however grow larger in size and may change shape with each moult.[4]

Snakes have smaller scales around the mouth and sides of the body which allow expansion so that a snake can consume prey of much larger width than itself.

Snake scales are made of keratin, the same material that hair and fingernails are made of.[4] They are cool and dry to touch.[7]

Surface and shape

Snake scales are of different shapes and sizes. Snake scales may be granular, have a smooth surface or have a longitudinal ridge or keel on it. Often, snake scales have pits, tubercles and other fine structures which may be visible to the naked eye or under a microscope. Snake scales may be modified to form fringes, as in the case of the Eyelash Bush Viper, Atheris ceratophora, or rattles as in the case of the rattlesnakes of North America.[8]

Certain primitive snakes such as boas, pythons and certain advanced snakes such as vipers have small scales arranged irregularly on the head. Other more advanced snakes have special large symmetrical scales on the head called shields or plates.[6]

Snake scales occur in variety of shapes. They may be :

- cycloid as in Family Typhlopidae.[9]

- long and pointed with pointed tips, as in the case of the Green Vine Snake Ahaetulla nasuta.[10]

- broad and leaf-like, as in the case of green pit vipers Trimeresurus spp.[10]

- as broad as they are long, for example, as in Rat snake Ptyas mucosus.[10]

- keeled weakly or strongly as in the case of the Buff-striped keelback Amphiesma stolatum.[10]

- with bidentate tips as in some spp of Natrix.[10]

- spinelike, juxtaposed as in the Short Seasnake Lapemis curtus.[6]

- large, non-overlapping knobs as in the case of the Javan Mudsnake Xenodermis javanicus.[6]

Another example of differentiation of snake scales is a transparent scale called the brille or spectacle which covers the eye of the snake. The brille is often referred to as a fused eyelid. It is shed as part of the old skin during moulting.[2]

Rattles

The most distinctive modification of the snake scale is the rattle of Rattlesnakes, such as those of the genera Crotalus and Sistrurus. The rattlesnake tail is made up of a series of loosely linked, interlocking chambers that when shaken, vibrate against one another to create the warning signal of a rattlesnake. Only the bottom button is firmly attached to the tip of the tail.[11]

A baby rattlesnake is born with only a small button or 'primordial rattle' which is firmly attached to the tip of the tail.[11] The first segment is added when a baby rattlesnake sheds its skin for the first time.[12] A new section is added each time the skin is shed until a rattle is formed. The rattle grows as the snake ages but segments are also prone to breaking off and hence the length of a rattle is not a reliable indicator of the age of a snake.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Colour

Scales, more specifically, mostly consist of hard beta keratins which are basically transparent. The colours of the scale are due to pigments in the inner layers of the skin and not due to the scale material itself. Scales are hued for all colours in this manner except for blue and green. Blue is caused by the ultrastructure of the scales. By itself, such a scale surface diffracts light and gives a blue hue, while, in combination with yellow from the inner skin it gives a beautiful iridescent green.

Some snakes have the ability to change the hue of their scales slowly. This is typically seen in cases where the snake becomes lighter or darker with change in season. In some cases, this change may take place between day and night.[4]

The shedding of scales is called ecdysis, or, in normal usage moulting or sloughing. In the case of snakes, the complete outer layer of skin is shed in one layer.[13] Snake scales are not discrete but extensions of the epidermis hence they are not shed separately, but are ejected as a complete contiguous outer layer of skin during each moult, akin to a sock being turned inside out.[4]

Moulting serves a number of functions - firstly, the old and worn skin is replaced, secondly, it helps get rid of parasites such as mites and ticks. Renewal of the skin by moulting is supposed to allow growth in some animals such as insects, however this view has been disputed in the case of snakes.[4][14]

Moulting is repeated periodically throughout a snake's life. Before a moult, the snake stops eating and often hides or moves to a safe place. Just prior to shedding, the skin becomes dull and dry looking and the eyes become cloudy or blue-colored. The inner surface of the old outer skin liquefies. This causes the old outer skin to separate from the new inner skin. After a few days, the eyes clear and the snake "crawls" out of its old skin. The old skin breaks near the mouth and the snake wriggles out aided by rubbing against rough surfaces. In many cases the cast skin peels backward over the body from head to tail, in one piece like an old sock. A new, larger, and brighter layer of skin has formed underneath.[4][15]

An older snake may shed its skin only once or twice a year, but a younger, still-growing snake, may shed up to four times a year.[15] The discarded skin gives a perfect imprint of the scale pattern and it is usually possible to identify the snake if this discard is reasonably complete and intact.[4]

Arrangement of scales

Snake have imbricate scales, overlapping like the tiles on a roof.[16] Snakes have rows of scales along the whole or part of their length and also many other specialised scales, either singly or in pairs, occurring on the head and other regions of the body.

The dorsal (or body) scales on the snake's body are arranged in rows along the length of their bodies. Adjacent rows are diagonally offset from each other. Most snakes have an odd number of rows across the body though certain species have an even number of rows e.g. Zaocys spp.[6] In the case of some aquatic and marine snakes, the scales are granular and the rows cannot be counted.[16]

The number of rows range from ten in Tiger Ratsnake Spilotes pullatus; thirteen in Dryocalamus, Liopeltis, Calamaria and Asian coral snakes of genus Calliophis; 65 to 75 in Python; 74 to 93 in Kolpophis and 130 to 150 in Acrochordus. The majority of the largest family of snakes, the Colubridae have 15, 17 or 19 rows of scales.[6][17]

The maximum number of rows are in mid-body and they reduce in count towards the head and on the tail.

Nomenclature of scales

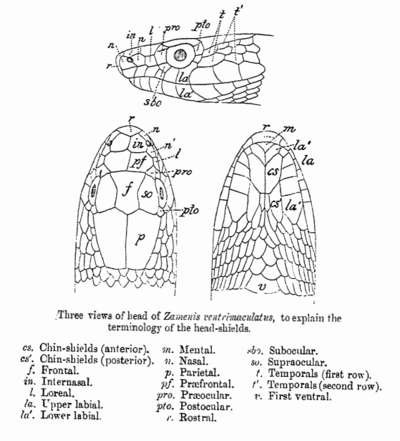

The various scales on a snake's head and body are indicated in the following paragraphs with annotated photographs of Buff-striped Keelback Amphiesma stolata (a common grass-snake of South Asia).

Head scales

Identification of scales is most conveniently begun with reference to the nostril which is easily identified on the snake. There are two scales enclosing the nostril which are called the nasals. The outer nasal (near the snout) is called the prenasal while the inner nasal (near the eye) is called the postnasal. Along the top of the snout connecting the nasals on both sides of the head are scales called internasals.

Between the two prenasals is a scale at the tip of the snout called the rostral scale.

The scales around the eye are called circumorbital scales and are named as 'ocular' scales but with appropriate prefix. The ocular scale proper is a transparent scale covering the eye which is called the spectacle, brille or eyecap.[4][18].

The circumorbital scales towards the snout or the front are called preocular scales, those towards the rear are called postocular scales and those towards the upper or dorsal side are called as supraocular scales. Circumorbital scales towards the ventral or lower side, if any, are called as subocular scales.

Between the preocular and the postnasal scales are the loreal scales.

The scales along the lips of the snake are called as labials. Those on the upper lip are called supralabials while those on the lower labial are called infralabials.

Between the eyeballs on top of the head, adjacent to the supraoculars are the frontal scales. The prefrontal scales are the scales connected to the frontals towards the tip of the snout which are in contact with the internasals.

The back of the top of the head has scales connected to the frontal scales called as the parietal scales. At the sides of the back of the head are scales called temporal scales.

On the underside of the head, a snake has an anterior scale called as the mental scale. Connected to the mental scales and all along the lower jaws are the infralabials. Along the lower jaw connected to infralabials are a pair of shields called the anterior chin shields. Next to the anterior chin shields, further back along the jaw are another pair of shields called the posterior chin shields.

Scales on the body

The scales on the body of the snake are called the dorsal or costal scales. Sometimes there is a special row of large scales along the top of the back of the snake, i.e, the uppermost row, called the vertebral scales.

The enlarged scales on the belly of the snake are called ventral scales or gastrosteges.

In "advanced" (Caenophidian) snakes, the broad belly scales and rows of dorsal scales correspond to the vertebrae, allowing scientists to count the vertebrae without dissection.

Tail scales

At the end of the ventral scales of the snake is an anal plate which protects the opening to the cloaca (a shared opening for waste and reproductive material to pass) on the underside near the tail. This anal scale may be single or divided into a pair. The part of the body beyond the anal scale is considered to be the tail.[11]

Sometimes snakes have enlarged scales, either single or paired, under the tail; these are called subcaudals or urosteges. These subcaudals may be smooth or keeled as in Bitis arietans somalica. The end of the tail may simply taper into a tip (as in the case of most snakes), it may form a spine (as in Acanthophis), end in a bony spur (as in Lachesis), a rattle (as in Crotalus), or a rudder as seen in many sea snakes.

Sources. Details for this section have been sourced from scale diagrams in Malcolm Smith.[19] Details of scales of Buff-striped Keelback have been taken from Daniels.[20]

Glossary of scales

- Scales on the head.

- Rostral.

- Nasorostral.

- Nasal.

- Internasal.

- Brille, spectacle, ocular scale, eyecap.

- Circumorbital.

- Loreal.

- Interorbital, Intersupraocular.

- Frontal.

- Prefrontal.

- Parietal.

- Occipital.

- Interoccipital.

- Temporal.

- Labial.

- Supralabial, Upper labial.

- Sublabial, Infralabial, Lower labial.

- Mental.

- Chin shield.

- Gular.

- Scales on the body.

- Scales on the tail.

Other pertinent terms

- Canthus, or Canthus rostralis.

- Mental groove.

Taxonomic importance

Scales do not play an important role in distinguishing between the families but are important at generic and specific level. There is an elaborate scheme of nomenclature of scales. Scales patterns, by way of scale surface or texture, pattern and colouration and the division of the anal plate, in combination with other morphological characteristics, are the principal means of classifying snakes down to species level.[21]

In certain areas in North America, where the diversity of snakes is not too large, easy keys based on simple identification of scales have been devised for the lay public to distinguish poisonous snakes from non-poisonous snakes.[22] [23] In other places with large biodiversity, such as Myanmar, publications caution that venomous and non-venomous snakes cannot be easily distinguished apart without careful examination.[24]

Identification of snakes by reference to scales seems an arcane art to the amateur naturalist because the nomenclature of snake scales seems esoteric and, more importantly, the snakes need to be caught and the head and body examined closely in hand for identification. The advent of high definition digital cameras means that images taken of snakes, if of appropriate definition and of the correct position, would show scales that can be examined, distinguished and counted without the need for catching and handling.

The scales patterning may also be used for individual identification in field studies. Clipping of specific scales to mark individual snakes is a popular approach to population estimation by mark and recapture techniques.

Distinguishing between venomous and non-venomous snakes

Finding out whether a snake is venomous or not is correctly done by identification of the species of a snake with the help of experts, or in their absence, close examination of the snake and using authoritative references on the snakes of the particular geographical region to identify it. Scale patterns help indicate the species and from the references, it can be verified if the snake species is venomous or not.

A point to note is that such identification requires a fair degree of knowledge about snakes, their taxonomy, snake-scale nomenclature as well as familiarity and access to authoritative scientific texts on snakes.

In certain regions, experts use presence or absence of certain scales to distinguish between non-venomous and venomous scales, with well-understood exceptions. For example, in relation to venomous snakes of Myanmar, the distribution of snakes permits the use of the presence or absence of loreal scales to distinguish between relatively harmless Colubrids and lethally venomous Elapids.[24]

The rule of hand for this region is that the absence of a loreal scale between the nasal scale and pre-ocular scale indicates that the snake is an Elapid and hence lethal.[24]

Please note that this rule-of-hand applies to terrestrial venomous snakes only and that vipers are an exception since they cannot be so classified due to the large number of small scales on the head. Subsequently a further check is to be carried out in the case of identified Colubrids to exclude known poisonous members of their family such as Rhabdopis species.[24]

In South Asia, it is adviseable to kill the snake which has bitten a person and carry it along to the hospital for possible identification by medical staff using scale diagrams so that an informed decision can be taken them as to whether anti-venin is to be administered or not.

Cultural significance

Snakes have been a motif in human culture and religion and an object of dread and fascination all over the world. The vivid patterns of snake scales, such as the Gaboon Viper, both repel and fascinate the human mind. Such patterns have inspired dread and awe in humans from pre-historic times and these can be seen in the art prevalent to those times. Studies of fear imagery and psychological arousal indicate that snake scales are a vital component of snake imagery. Snake scales also appear to have affected Islamic art in the form of tessallated mosaic patterns which show great similarity to snake-scale patterns.[25]

Snakeskin, with its highly periodic cross-hatch or grid patterns, appeals to people's aesthetics and have been used to manufacture many leather articles including fashionable accessories.[25] The use of snakeskin has however endangered snake populations[26] and resulted in international restrictions in trade of certain snake species and populations in the form of CITES provisions.[27] Animal lovers in many countries now propagate the use of artificial snakeskin instead, which are easily produced from embossed leather, patterned fabric, plastics and other materials.[25]

Snake scales occur as a motif regularly in computer action games.[28] [29] [30] [31]

A snake scale was portrayed as a clue in the 1982 sci-fi cum film noir called 'Blade Runner'.[32]

Snake scales also figure in popular fiction, such as the Harry Potter series (dessicated Boomslang skin is used as a raw material for concocting the Polyjuice potion), and also in teen fiction.[33]

Cited references

- ^ Boulenger, George A. 1890 The Fauna of British India. page 1

- ^ a b The Snakes of Indiana at The Centre for Reptile and Amphibian Conservation and Management, Indiana. Accessed 14 August 2006.

- ^ - Evolution, Snakes And Humans - Appearance and behavior of Encyclopaedia volume 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Are snakes slimy? at Singapore Zoological Garden's Docent. Accessed 14 August 2006.

- ^ Kentucky Snake Publication (pdf). University of Kentucky

- ^ a b c d e f Greene, Harry W. Snakes - The Evolution of Mystery in Nature, page 22

- ^ Herpetology FAQ at San Diego Museum of Natural History. Accessed 14 August 2006.

- ^ Greene, Harry W. Snakes - The Evolution of Mystery in Nature, page 23

- ^ Boulenger, George A. The Fauna of British India... page 234

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Malcolm A. Fauna of British India...Vol III - Serpentes, page 6

- ^ a b c Reptiles - Snake facts. Columbus Zoo & Aquarium.

- ^ Snake Rattles! Ask a scientist! (Zoology archive). Newton BBS, Argonne National Laboratory.

- ^ Smith, Malcolm A. Fauna of British India...Vol I - Loricata and Testudines, page 30

- ^ ZooPax Scales Part 3

- ^ a b General Snake Information - Division of Wildlife, South Dakota

- ^ a b Smith, Malcolm A. Fauna of British India...Vol III - Serpentes, page 5

- ^ Smith, Malcolm A. Fauna of British India...Vol III - Serpentes, page 7

- ^ Evolution of snakes. Accessed 21 August 2006.

- ^ Smith, Malcolm A. Fauna of British India. Vol III - Serpentes, page 29

- ^ Daniels, J.C. Book of Indian Reptiles and Amphibians. Pages 116-118

- ^ How to identify snakes - Kentucky snake identification. University of Kentucky

- ^ North Carolina State Wildlife Damage Notes - Snakes

- ^ Pennsylvania State University - Wildlife Damage Control 15 (pdf)

- ^ a b c d Leviton AE, Wogan GOU, Koo MS, Zug GR, Lucas RS, Vindum JV. 2003. The Dangerously Venomous Snakes of Myanmar, Illustrated Checklist with Keys. Proc. Cal. Acad. Sci. 54 (24):407-462. PDF at Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. Accessed 8 August 2006.

- ^ a b c Voland,Eckart and Grammer,Karl - Evolutionary Aesthetics, (2003) Springer, ISBN 3-540-43670-7. pages 108-116 ( Accessed through Google Book Search beta on 14 August 2006).

- ^ The Endangered Species Handbook - Trade (chapter) Reptile Trade - Snakes and Lizards (section) - accessed on 15 August 2006

- ^ Species in Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) - accessed on 14 August 2006

- ^ Gabriel Knight - Sins of the Father ( Accessed on 16 August 2006).

- ^ Snake Rattle 'n Roll ( Accessed on 16 August 2006).

- ^ Allahkazam's Magical Realm ( Accessed on 16 August 2006).

- ^ Legend of Mana ( Accessed on 16 August 2006).

- ^ BRMovie.com Encyclopaedia ( Accessed on 16 August 2006).

- ^ Jade Green and Jade White

Other references

- Boulenger, George A., (1890), The Fauna of British India including Ceylon and Burma, Reptilia and Batrachia. Taylor and Francis, London.

- Daniels, J.C. Book of Indian Reptiles and Amphibians. (2002). BNHS. Oxford University Press. Mumbai.

- Greene, Harry W. (2004), Snakes - The Evolution of Mystery in Nature. University of California Press, pages 22-23 (excerpted from Google Book Search beta on 07 August 2006).

- Leviton AE, Wogan GOU, Koo MS, Zug GR, Lucas RS, Vindum JV. 2003. The Dangerously Venomous Snakes of Myanmar, Illustrated Checklist with Keys. Proc. Cal. Acad. Sci. 54 (24):407-462. PDF at Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles.

- Mallow D, Ludwig D, Nilson G. 2003. True Vipers: Natural History and Toxinology of Old World Vipers. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, Florida. 359 pp. ISBN 0-89464-877-2.

- Smith, Malcolm A. (1943), The Fauna of British India, Ceylon and Burma including the whole of the Indo-Chinese Sub-region, Reptilia and Amphibia. Vol I - Loricata and Testudines, Vol II-Sauria, Vol III-Serpentes. Taylor and Francis, London.

External links

- San Diego Museum of Natural History Herpetology FAQ

- Are snakes slimy - Singapore Zoological Garden's Docent site

- Microscopic structure of smooth and keeled scales in snakes

- How to identify snakes - Kentucky snake identification. University of Kentucky

- Kentucky Snake Publication (pdf). University of Kentucky

- The Snakes of Indiana - The Centre for Reptile and Amphibian Conservation and Management, Indiana

- General Snake Information - Division of Wildlife, South Dakota

- Reptiles - Snake facts. Columbus Zoo & Aquarium.

- North Carolina State Wildlife Damage Notes - Snakes

- Pennsylvania State University - Wildlife Damage Control 15 (pdf)

- ZooPax Scales Part 3

- Species in Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) - accessed on 14 August 2006.

- The Endangered Species Handbook - Trade (chapter) Reptile Trade - Snakes and Lizards (section) - accessed on 15 August 2006.