Battle of Cannae

- For the 11th-century battle in the Byzantine conquest of the Mezzogiorno, see Battle of Cannae (1018).

| Battle of Cannae | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||

| File:Hannibal's route of invasion, 3rd century BC.gif Hannibal's route of invasion. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Carthage | Roman Republic | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hannibal |

Gaius Terentius Varro, Lucius Aemilius Paullus † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

40,000 heavy infantry, 6,000 light infantry, 8,000 cavalry | 86,400–87,000 men (16 Roman and Allied legions) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

6,000 killed, 10,000 wounded |

70,000 killed (Polybius), 50,000 killed (Livy), around 11,000 captured | ||||||

The Battle of Cannae was a major battle of the Second Punic War, taking place on August 2, 216 BC near the town of Cannae in Apulia in southeast Italy. The Carthaginian army under Hannibal decisively defeated a numerically superior Roman army under command of the consuls Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro. Following the Battle of Cannae, Capua and several other Italian city-states defected from the Roman Republic. Although the battle failed to decide the outcome of the war in favour of Carthage, it is regarded as one of the greatest tactical feats in military history and the greatest defeat of Rome.

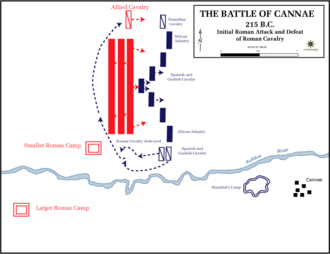

Having recovered from their previous losses at Trebia (218 BC) and Trasimene (217 BC), the Romans decided to confront Hannibal at Cannae, with roughly 87,000 Roman and Allied troops. With their right wing positioned near the Aufidus River, the Romans placed their cavalry on their flanks and massed their heavy infantry in a deeper formation than in the usual centre. Perhaps the Romans hoped to break the Carthaginian line earlier in the battle than they had at the Battle of Trebia. To counter this, Hannibal utilized the double-envelopment tactic. He drew up his least reliable infantry in the centre, with the flanks composed of Carthaginian cavalry. Before engaging the Romans, however, his lines adopted a crescent shape — advancing his centre with his veteran troops at the wings in echelon formation. Upon the onset of the battle, the Carthaginian centre withdrew before the advance of the numerically superior Romans. While Hannibal's centre line yielded, the Romans had unknowingly driven themselves into a large arc — whereupon the Carthaginian infantry and cavalry (positioned on the flanks) encircled the main body of Roman infantry. Surrounded and attacked on all sides with no means of escape, the Roman army was subsequently cut to pieces. An estimated 60,000–70,000 Romans were killed or captured at Cannae (including the consul Lucius Aemilius Paullus and eighty Roman senators). In terms of the number of lives lost in a single day, Cannae is estimated to be within the thirty costliest battles in all of recorded human history. Ernlee Bradford, a biographer of Hannibal claims that the 50,000 Romans killed represents the largest number of troop felled in battle in a single day.

Strategic background

Shortly after the start of the Second Punic War, the Carthaginian general Hannibal had boldly crossed into Italy by traversing the Alps during the winter, and had quickly won two major victories over the Romans at Trebia and at Lake Trasimene. After suffering these losses, the Romans appointed Fabius Maximus as dictator to deal with the threat. Fabius set about fighting a war of attrition against Hannibal, cutting off his supply lines and refusing to engage in pitched battle. These tactics proved unpopular with the Romans. As the Roman people recovered from the shock of Hannibal's initial victories, they began to question the wisdom of the Fabian strategy which had given the Carthaginian army the chance to regroup.[1] Fabius's strategy was especially frustrating to the majority of the people who were eager to see a quick conclusion to the war. It was also widely feared that if Hannibal continued plundering Italy unopposed, Rome's allies might doubt Rome's ability to protect them, and defect to Carthage's cause.

Unimpressed with Fabius's strategy, the Roman Senate did not renew his dictatorial powers at the end of his term, and command was given back to the consuls Gnaeus Servilius Geminus and Gaius Flaminius. In 216 BC, elections resumed with Gaius Terentius Varro and Lucius Aemilius Paullus elected as consuls and given command of a newly raised army of unprecedented size in order to counter Hannibal. Polybius writes:

The Senate determined to bring eight legions into the field, which had never been done at Rome before, each legion consisting of five thousand men besides allies. […] Most of their wars are decided by one Consul and two legions, with their quota of allies; and they rarely employ all four at one time and on one service. But on this occasion, so great was the alarm and terror of what would happen, they resolved to bring not only four but eight legions into the field.

- — Polybius, The Histories of Polybius[2]

These eight legions, along with an estimated 2,400 Roman cavalry, formed the nucleus of this massive new army. As each legion was accompanied by an equal number of allied troops, and allied cavalry numbered around 4,000, the total strength of the army which faced Hannibal could not have been much less than 90,000.[3]

Prelude

In the spring of 216 BC, Hannibal took the initiative and seized the large supply depot at Cannae in the Apulian plain. He thus placed himself between the Romans and their crucial source of supply. As Polybius notes, the capture of Cannae "caused great commotion in the Roman army; for it was not only the loss of the place and the stores in it that distressed them, but the fact that it commanded the surrounding district".[2] The consuls, resolving to confront Hannibal, marched southward in search of the Carthaginian general. After two days’ march, they found him on the left bank of the Aufidus River and encamped six miles away. Ordinarily each of the two Consuls would command their own portion of the army, but since the two armies were combined into one, the Roman law required them to alternate their command on a daily basis. It appears that Hannibal had already figured out that the command of the Roman army alternated, and planned his strategy accordingly.

Reportedly, a Carthaginian officer named Gisgo commented on how much larger the Roman army was. Hannibal replied, "another thing that has escaped your notice, Gisgo, is even more amazing — that although there are so many of them, there is not one among them called Gisgo."[4]

Consul Varro, who was in command on the first day, is presented in our sources as a man of reckless nature and hubris, and was determined to defeat Hannibal. While the Romans were approaching Cannae, a small portion of Hannibal's forces ambushed the Roman army. Varro successfully repelled the Carthaginian attack and continued on his way to Cannae. This victory, though essentially a mere skirmish with no lasting strategic value, greatly bolstered confidence in the Roman army, perhaps to overconfidence on Varro's part. Paullus, however, was opposed to the engagement as it was taking shape. Unlike Varro, he was prudent and cautious, and he believed it was foolish to fight on open ground, despite the Romans' numerical strength. This was especially true since Hannibal held the advantage in cavalry (both in quality and numerical terms). Despite these misgivings, Paullus thought it unwise to withdraw the army after the initial success, and camped two-thirds of the army east of the Aufidus River, sending the remainder of his men to fortify a position on the opposite side. The purpose of this second camp was to cover the foraging parties from the main camp and harass those of the enemy.[3]

The two armies stayed in their respective locations for two days. During the second of these two days (August 1), Hannibal, well aware that Varro would be in command the following day, left his camp and offered battle. Paullus, however, refused. When his request was rejected, Hannibal, recognizing the importance of the Aufidus' water to the Roman troops, sent his cavalry to the smaller Roman camp to harass water-bearing soldiers that were found outside the camp fortifications. According to Polybius,[2] Hannibal's cavalry boldly rode up to the edge of the Roman encampment, causing havoc and thoroughly disrupting the supply of water to the Roman camp.[5] Enraged by this foray, Varro assumed command on August 2, marshaled his forces, and crossed back over the Aufidus to do battle.

Battle

Forces

The combined forces of the two consuls totaled 75,000 infantry, 2,400 Roman cavalry and 4,000 allied horse (involved in the actual battle) and, in the two fortified camps, 2,600 heavily-armed men, 7,400 lightly-armed men (a total of 10,000), so that the total strength the Romans brought to the field amounted to approximately 86,400 men. Opposing them was a Carthaginian army composed of roughly 40,000 heavy infantry, 6,000 light infantry, and 8,000 cavalry in the battle itself, irrespective of detachments.[6] The Carthaginian army was a combination of warriors from numerous regions. Along with the core of 8,000 Libyans, armed with Roman armour, fought 8,000 Spaniards, 16,000 Gauls (8,000 were left at camp the day of battle) and an unknown number of Gaetulian Infantry. Hannibal's cavalry also came from diverse backgrounds. He commanded 4,000 Numidian, 2,000 Spanish, and 450 Liby-Phoenician cavalry. Finally, Hannibal had around 8,000 skirmishers comprised Balearian slingers and mixed nationality spearmen. All of these specific groups brought their respective strengths to the battle. The uniting factor for the Carthaginian army was the personal tie each group had with Hannibal.[7]

Equipment

Rome's forces used traditional Roman equipment including pila and hastae as weapons as well as traditional helmets, shields, and body armor. On the other hand, the Carthaginian army used a variety of equipment. Libyans fought with both armor and equipment taken from previously defeated Romans. Spaniards fought with swords suited for cutting and thrusting, javelins, and incendiary spears. For defense Spanish warriors carried large oval shields. The Gauls on the other hand carried long slashing swords and small but sturdy oval shields. The heavy Carthaginian cavalry carried two javelins and a curved slashing sword with a heavy shield for protection. Numidians, being light cavalry, used no armor but carried a small shield, javelins, and a sword. Skirmishers acting as light infantry carried either slings or spears. The Balearian slingers, who were famous for their accuracy, carried short, medium, and long slings used to throw stones but no defensive equipment. Spearmen carried shields, javelins, and possibly swords or a stabbing spear.[7]

Tactical deployment

The conventional deployment for armies of the time was to place infantry in the center and deploy the cavalry in two flanking "wings". The Romans followed this convention fairly closely, but chose extra depth (by stacking their cohorts), rather than breadth for their infantry line, hoping to use this concentration of forces to quickly break through the center of Hannibal's line. Varro knew how the Roman infantry had managed to penetrate Hannibal's center during the Battle of the Trebia, and he planned to recreate this on an even greater scale. The principes were stationed immediately behind the hastati, ready to push forward at first contact to ensure the Romans presented a unified front. As Polybius wrote, "the maniples were nearer each other, or the intervals were decreased… and the maniples showed more depth than front".[2][8] Even though they outnumbered the Carthaginians, this depth-oriented deployment meant that the Roman lines had a front of roughly equal size to their numerically inferior opponents.

To Varro, Hannibal seemed to have little room to manoeuver and no means of retreat as he was deployed with the Aufidus River to his rear. Varro believed that when pressed hard by the Romans' superior numbers, the Carthaginians would fall back onto the river and, with no room to manoeuver, would be cut down in panic. Bearing in mind that Hannibal's two previous victories had been largely decided by his trickery and ruse, Varro had sought an open battlefield. The field at Cannae was indeed clear, with no possibility of hidden troops being brought to bear as an ambush.[9]

Hannibal, on the other hand, had deployed his forces based on the particular fighting qualities of each unit, taking into consideration both their strengths and weaknesses in devising his strategy.[3] He placed his Iberians, Gauls and Celtiberians in the middle, alternating the ethnic composition across the front line. Hannibal's infantry from Punic Africa was positioned on the wings at the very edge of his infantry line.

It is a common misconception that Hannibal's African troops carried pikes—a theory put forward by historian Peter Connolly. The Libyan troops in fact carried spears "shorter than the Roman Triarii". Their advantage was not that they had pikes, it was that these infantry were expertly battle-hardened, remained cohesive, and attacked the Roman flanks.

Hasdrubal led the Iberian and Celtiberian cavalry on the left (south near the Aufidus River) of the Carthaginian army. Hasdrubal was given about 6,500 cavalry, and Hanno had 3,500 Numidians on the right. Hasdrubal's force was able to quickly destroy the Roman cavalry (on the south), pass the Roman's infantry rear, and reach the Roman allied cavalry while they were engaged with Hanno's Numidians. The combined cavalry forces of Hasdrubal and Hanno dispersed the Roman's allied cavalry and attacked the Roman infantry from the rear.

Hannibal intended that his cavalry, comprising mainly medium Hispanic cavalry and Numidian light horse, and positioned on the flanks, defeat the weaker Roman cavalry and swing around to attack the Roman infantry from the rear as it pressed upon Hannibal's weakened center. His veteran African troops would then press in from the flanks at the crucial moment, and encircle the overextended Roman army.

After encirclement, a combination of factors aided the decisive victory. First of all, instead of attacking a hardened line of the veteran triarii usually at the rear, the cavalry actually finished off the skirmishers who had retreated through the ranks towards the rear after the skirmish was complete. This allowed time for the Carthaginian army to strategically remove century leaders as well as scare the hastati into confusion. The confusion only worsened as with the aerial bombardment that produced only minor wounds but tricked both sides of the Roman forces to flee towards the middle. This fleeing only led to a situation where Roman troops were too tightly packed to effectively use their weapons and thus fell even quicker.

Hannibal was unconcerned about his position against the Aufidus River; in fact, it played a major factor in his strategy. By anchoring his army on the river, Hannibal prevented one of his flanks from being overlapped by the more numerous Romans. The Romans were in front of the hill leading to Cannae and hemmed in on their right flank by the Aufidus River, so that their left flank was the only viable means of retreat.[10] In addition, the Carthaginian forces had manoeuvered so that the Romans would face east. Not only would the morning sunlight shine on the Romans, but the southeasterly winds would blow sand and dust into their faces as they approached the battlefield.[8] Hannibal's unique deployment of his army, based on his perception and understanding of the capabilities of his troops, was decisive.

Events

As the armies advanced on one another, Hannibal gradually extended the center of his line, as Polybius describes: "After thus drawing up his whole army in a straight line, he took the central companies of Hispanics and Celts and advanced with them, keeping the rest of them in contact with these companies, but gradually falling off, so as to produce a crescent-shaped formation, the line of the flanking companies growing thinner as it was prolonged, his object being to employ the Africans as a reserve force and to begin the action with the Hispanics and Celts."[3] Polybius describes the weak Carthaginian center as deployed in a crescent, curving out toward the Romans in the middle with the African troops on their flanks in echelon formation.[2] It is believed that the purpose of this formation was to break the forward momentum of the Roman infantry, and delay its advance before other developments allowed Hannibal to deploy his African infantry most effectively.[11] However, some historians have called this account fanciful, and claim that it represents either the natural curvature that occurs when a broad front of infantry marches forward, or the bending back of the Carthaginian center from the shock action of meeting the heavily massed Roman center.[11]

When the battle was joined, the cavalry engaged in a fierce exchange on the flanks. Polybius describes the scene,[2] writing that "When the Hispanic and Celtic horses on the left wing came into collision with the Roman cavalry, the struggle that ensued was truly barbaric."[3] Here, the Carthaginian cavalry quickly overpowered the inferior Romans on the right flank and routed them. A portion of the Carthaginian cavalry then detached itself from the Carthaginian left flank and made a wide circling pivot to the Roman right-flank, where it fell upon the rear of the Roman cavalry. The Roman cavalry was immediately dispersed as the Carthaginians fell upon them and began "cutting them down mercilessly".[3]

While the Carthaginians were in the process of defeating the Roman cavalry, the mass of infantry on both sides advanced towards each other in the center of the field. As the Romans advanced, the wind from the East blew dust in their faces and obscured their vision. While the wind itself was not a major factor, the dust that both armies created would have been potentially debilitating to sight.[8] Although the dust made sight difficult, troops would still have been able to see others in the vicinity, thus, since troops fought amongst close friends they would still see the gruesome deaths. The dust, however, was not the only psychological factor involved in battle. Because of the somewhat distant battle location both sides were forced to fight on little sleep. The Romans faced another disadvantage caused by lack of proper hydration due to Hannibal's attack on the Roman encampment during the previous day. Furthermore, the massive number of troops would have led to an overwhelming amount of background noise. All of these psychological factors made battle especially difficult for the infantrymen.[7]

Hannibal stood with his men in the weak center and held them to a controlled retreat. The crescent of Hispanic and Gallic troops buckled inwards as they gradually withdrew. Knowing the superiority of the Roman infantry, Hannibal had instructed his infantry to withdraw deliberately, thus creating an even tighter semicircle around the attacking Roman forces. By doing so, he had turned the strength of the Roman infantry into a weakness. Furthermore, while the front ranks were gradually advancing forward, the bulk of the Roman troops began to lose their cohesion, as they began crowding themselves into the growing gap. Soon they were compacted together so closely that they had little space to wield their weapons. In pressing so far forward in their desire to destroy the retreating and collapsing line of Hispanic and Gallic troops, the Romans had ignored (possibly due to the dust previously mentioned) the African troops that stood uncommitted on the projecting ends of this now reversed-crescent.[11] This also gave the Carthaginian cavalry time to drive the Roman cavalry off on both flanks and attack the Roman center in the rear. The Roman infantry, now stripped of both its flanks, formed a wedge that drove deeper and deeper into the Carthaginian semicircle, driving itself into an alley that was formed by the African Infantry stationed at the echelons.[3] At this decisive point, Hannibal ordered his African Infantry to turn inwards and advance against the Roman flanks, creating an encirclement of the Roman infantry in the earliest known example of the pincer movement.

When the Carthaginian cavalry attacked the Romans in the rear, and the African flanking echelons had assailed them on their right and left, the advance of the Roman infantry was brought to an abrupt halt. The trapped Romans were enclosed in a pocket with no means of escape. The Carthaginians created a wall and began destroying the entrapped Romans as discussed earlier. Polybius claims that, "as their outer ranks were continually cut down, and the survivors forced to pull back and huddle together, they were finally all killed where they stood."

Recognizing that his ploy had resulted in near-total victory and still needing to consolidate his gains and take only those few prisoners who would be willing to genuinely defect, Hannibal ordered his men to speedily cut the hamstrings of surviving enemies and move onto the next available Roman, and then later in the day — when there was no more able-bodied resistance — to butcher the lamed Romans at their leisure.

As Livy describes, "So many thousands of Romans were lying […] Some, whom their wounds, pinched by the morning cold, had roused, as they were rising up, covered with blood, from the midst of the heaps of slain, were overpowered by the enemy. Some were found with their heads plunged into the earth, which they had excavated; having thus, as it appeared, made pits for themselves, and having suffocated themselves."[3] Nearly six hundred legionnaires were slaughtered each minute until darkness brought an end to the bloodletting.[12] Only 14,000 Roman troops managed to escape (most of whom had cut their way through to the nearby town of Canusium). At the end of the day, out of the original force of 87,000 Roman troops, only about one out of every six men was still alive.[3]

Casualties

Although the true figure will probably never be known, Livy and Polybius variously claim that 50,000-70,000 Romans died with about 3,000–4,500 taken prisoner.[8] Among the dead were Lucius Aemilius Paullus himself, as well two consuls for the preceding year, two quaestors, twenty-nine out of the forty-eight military tribunes, and an additional eighty senators (at a time when the Roman Senate was comprised of no more than 300 men, this constituted 25–30% of the governing body). Another 8,000 from the two Roman camps and the neighboring villages surrendered on the following day (after further resistance cost even more fatalities - more or less 2,000). In all, perhaps more than 75,000 Romans of the original force of 87,000 were dead or captured — totaling more than 85% of the entire army. In the battle itself only, perhaps more of 95% of the Romans and allies were killed or captured. More Romans were lost at Cannae than in any other battle except the Battle of Arausio, and Cannae is second only to the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest when looking at the percentage of Romans killed. For their part, the Carthaginians suffered 16,700 casualties (with the Celtiberians and Iberians accounting for the majority). The fatalities for the Carthaginians amounted to 6,000 men, of whom 4,000 were Celtiberians, 1,500 Iberians and Africans, and the remainder cavalry.[3]

The total casualty figure of the battle, therefore, exceeds 80,000 men. At the time when Cannae was fought, it was probably the second most costly battle in history, behind only the Battle of Plataea, even if at Plateae the bulk of the casualties was made in the rout of the Persian's army after the battle and not necessarily in the battlefield itself. Until the Mongol invasions, ~1500 years later, it was ranked in the ten most costly battles in human history, and even in modern times the death toll remains in the fifty most lethal battles in world history.

Aftermath

Never before, while the City itself was still safe, had there been such excitement and panic within its walls. I shall not attempt to describe it, nor will I weaken the reality by going into details… it was not wound upon wound but multiplied disaster that was now announced. For according to the reports two consular armies and two consuls were lost; there was no longer any Roman camp, any general, any single soldier in existence; Apulia, Samnium, almost the whole of Italy lay at Hannibal's feet. Certainly there is no other nation that would not have succumbed beneath such a weight of calamity.

For a brief period of time, the Romans were in complete disarray. Their best armies in the peninsula were destroyed, the few remnants severely demoralized, and the only remaining consul (Varro) completely discredited. It was a complete catastrophe for the Romans. As the story goes, Rome declared a national day of mourning, as there was not a single person in Rome who was not either related to or acquainted with a person who had died. The Romans became so desperate that they resorted to human sacrifice, twice burying people alive[14] at the Forum of Rome and abandoning an oversized baby in the Adriatic Sea[14] (perhaps one of the last recorded instances of human sacrifices the Romans would perform, unless the public executions of defeated enemies dedicated to Mars are counted as human sacrifice).

Lucius Caecilius Metellus, a military tribune, is known to have so much despaired in the Roman cause in the aftermath of the battle as to suggest that everything was lost, and called the other tribunes to sail overseas and hire themselves up into the service to some foreign prince.[6] Afterwards, he was forced by his own example to swear an oath of allegiance to Rome for all time. Furthermore, the Roman survivors of Cannae were later reconstituted as two legions and assigned to Sicily for the remainder of the war as punishment for their humiliating desertion of the battlefield.[6] In addition to the physical loss of her army, Rome would suffer a symbolic defeat of prestige. A gold ring was a token of membership in the upper classes of Roman society;[6] Hannibal had his men collect more than 200 gold rings from the corpses on the battlefield, and sent this collection to Carthage as proof of his victory. The collection was poured on the floor in front of the Carthaginian Senate, and was judged to be "three and a half measures".

Hannibal, having gained yet another victory (following the battles of Trebia and Lake Trasimene), had defeated the equivalent of eight consular armies.[15] Within just three campaign seasons, Rome had lost a fifth of the entire population of citizens over seventeen years of age (nearly twelve percent of Rome's available manpower).[3] Furthermore, the morale effect of this victory was such that most of Southern Italy joined Hannibal's cause. After the Battle of Cannae, the Hellenistic southern provinces of Arpi, Salapia, Herdonia, Uzentum, including the cities of Capua and Tarentum (two of the largest city-states in Italy) all revoked their allegiance to Rome and pledged their loyalty to Hannibal. As Polybius notes, "How much more serious was the defeat of Cannae, than those which preceded it can be seen by the behavior of Rome’s allies; before that fateful day, their loyalty remained unshaken, now it began to waver for the simple reason that they despaired of Roman Power."[2] During that same year, the Greek cities in Sicily were induced to revolt against Roman political control, while the Macedonian king, Philip V, had pledged his support to Hannibal — thus initiating the First Macedonian War against Rome. Hannibal also secured an alliance with the newly appointed King Hieronymus of Syracuse, the only independent leftover in Sicily.

Following the battle, Livy states that Hannibal's officers wanted to march directly on Rome.[16] Yet despite the tremendous human and material losses inflicted on the Romans, the defection of several Roman allies and the declaration of war by Philip and Hieronymus, the Punic forces lacked the ability and resources to conduct a sustained siege of Rome which still was unlikely to be taken quickly.[17] Moreover, it would have been nearly impossible to march the entire Carthaginian army the more than 400 km from Cannae to Rome in order to begin a siege. Many argue that Rome, perhaps due to its being at war, was certainly not undefended, and another prolonged battle and siege after such a long march would prove extremely difficult. Finally, that Hannibal refused to march on Rome after his victories at Trasimene (217 BC) and Cannae (216 BC), and that he first laid siege to the city in 212 suggests that his plan was never to take the city. Hannibal likely desired to force Rome to capitulate after a long series of battlefield defeats and the loss of its allies.[18] According to Livy, Hannibal's refusal to move next to Rome was much to the distress of Maharbal, the commander of the Numidian cavalry, whom he famously quotes as saying, "Truly the Gods have not bestowed all things upon the same person. Thou knowest indeed, Hannibal, how to conquer, but thou knowest not how to make use of your victory."[3] Instead, Hannibal sent a delegation led by Carthalo to negotiate a peace treaty with the Senate on moderate terms. Yet despite the multiple catastrophes Rome had suffered, the Roman Senate refused to parley. Instead, they re-doubled their efforts, declaring full mobilization of the male Roman population, and raised new legions from landless peasants and even slaves. So firm were these measures that the word “peace” was prohibited, mourning was limited to only thirty days, and public tears were restricted to women.[19][3] The Romans, after experiencing this catastrophic defeat and losing other battles, had at this point learned their lesson. For the remainder of the war in Italy, they would no longer engage in pitched battles against Hannibal; instead they would utilize the strategies Fabius had taught them, which — as they had finally realized — were the only feasible means of driving Hannibal from Italy.

In the long run, Rome had its revenge. A Roman fleet carried a Roman army to Africa, where in the Battle of Zama, Scipio Africanus defeated Hannibal, effectively ending the 2nd Punic War.

Historical significance

Effects on Roman military doctrine

The Battle of Cannae played a major role in shaping the military structure and tactical organization of the Roman Republican army. At Cannae, the Roman infantry assumed a formation similar to the Greek phalanx. This delivered them into Hannibal's trap, since their inability to manoeuvre independently from the mass of the army made it impossible for them to counter the encircling tactics employed by the Carthaginian cavalry. Furthermore, the strict laws of the Roman state required that high command alternate between the two consuls — thus restricting strategic consistency. However, in the years following Cannae, striking reforms were introduced to address these deficiencies. First, the Romans "articulated the phalanx, then divided it into columns, and finally split it up into a great number of small tactical bodies that were capable, now of closing together in a compact impenetrable union, now of changing the pattern with consummate flexibility, of separating one from the other and turning in this or that direction." For instance, at Ilipa and Zama, the principes were formed up well to the rear of the hastati — a deployment that allowed a greater degree of mobility and manoeuverability. The culminating result of this change marked the transition from the traditional manipular system to the cohort under Gaius Marius, as the basic infantry unit of the Roman army.

In addition, the necessity of a unified command was finally recognized. After various political experiments, Scipio Africanus was made general-in-chief of the Roman armies in Africa, and was assured the continued occupancy of this title for the duration of the war. This appointment may have violated the constitutional laws of the Roman Republic, but, as Hans Delbrück wrote, "effected an internal transformation that increased her military potentiality enormously" while foreshadowing the decline of the Republic's political institutions. Furthermore, the battle exposed the limits of a citizen-militia army. Following Cannae, the Roman army gradually developed into a professional force: the nucleus of Scipio's army at Zama was composed of veterans who had been fighting the Carthaginians in Hispania for nearly sixteen years, and had been molded into a superb fighting force.

Status in military history

The Battle of Cannae is as famous for Hannibal's tactics as it is for the role it played in Roman history. Not only did Hannibal inflict a defeat on the Roman Republic in a manner unrepeated for over a century until the lesser-known Battle of Arausio, the battle itself has acquired a significant reputation within the field of military history. As military historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge once wrote: "Few battles of ancient times are more marked by ability… than the battle of Cannae. The position was such as to place every advantage on Hannibal's side. The manner in which the far from perfect Hispanic and Gallic foot was advanced in a wedge in échelon… was first held there and then withdrawn step by step, until it had the reached the converse position… is a simple masterpiece of battle tactics. The advance at the proper moment of the African infantry, and its wheel right and left upon the flanks of the disordered and crowded Roman legionaries, is far beyond praise. The whole battle, from the Carthaginian standpoint, is a consummate piece of art, having no superior, few equal, examples in the history of war". As Will Durant wrote, "It was a supreme example of generalship, never bettered in history… and [it] set the lines of military tactics for 2,000 years".

Hannibal's double envelopement at the Battle of Cannae is often viewed as one of the greatest battlefield manoeuvers in history, and is cited as the first successful use of the pincer movement within the Western world, to be recorded in detail.[20]

The "Cannae Model"

Apart from it being one of the greatest defeats ever inflicted on Roman arms, the Battle of Cannae represents the archetypal battle of annihilation, a strategy that has rarely been successfully implemented in modern history. As Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in World War II, once wrote, "Every ground commander seeks the battle of annihilation; so far as conditions permit, he tries to duplicate in modern war the classic example of Cannae". Furthermore, the totality of Hannibal's victory has made the name "Cannae" a byword for military success, and is today studied in detail in several military academies around the world. The notion that an entire army could be encircled and annihilated within a single stroke, led to a fascination among subsequent Western generals for centuries (including Frederick the Great and Helmuth von Moltke) who attempted to emulate its tactical paradigm of envelopment and re-create their own "Cannae".[12] For instance, Norman Schwarzkopf, the commander of the Coalition Forces in the Gulf War, studied Cannae and employed the principles Hannibal used, in his highly successful ground campaign against the much less impressive Iraqi forces.[6]

Hans Delbrück's seminal study of the battle had a profound influence on subsequent German military theorists, in particular, the Chief of the German General Staff, Alfred Graf von Schlieffen (whose eponymously-titled "Schlieffen Plan" was inspired by Hannibal's double envelopment manoeuver). Through his writings, Schlieffen taught that the "Cannae model" would continue to be applicable in maneuver warfare throughout the 20th century: "A battle of annihilation can be carried out today according to the same plan devised by Hannibal in long forgotten times. The enemy front is not the goal of the principal attack. The mass of the troops and the reserves should not be concentrated against the enemy front; the essential is that the flanks be crushed. The wings should not be sought at the advanced points of the front but rather along the entire depth and extension of the enemy formation. The annihilation is completed through an attack against the enemy's rear… To bring about a decisive and annihilating victory requires an attack against the front and against one or both flanks…" Schlieffen later developed his own operational doctrine in a series of articles, many of which were later translated and published in a work entitled "Cannae".

Cultural references

- The Battle of Cannae served as an inspiration for the American metal band Cannae.

- Emmanuel Lasker, a famous German chess player, was particularly fond of using the Battle of Cannae to illustrate chess strategies and tactics.

- Due to the similarities in tactics, the Battle of Cowpens is often referred to as the "American Cannae" or "Cannae in miniature".

- The Rome: Total War Engine was used to produce a computerized recreation of the battle in The History Channel series Decisive Battles and the BBC series Time Commanders (in the latter, this recreation was used to refight the battle, with the computer as Rome and the players as Carthage, and ending in a Carthaginian defeat ).

Notes and references

- ^ Liddell Hart, Basil, Strategy, New York City, New York, Penguin Group, 1967

- ^ a b c d e f g "Internet Ancient History Sourcebook". Cite error: The named reference "polybius" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Cottrell, Leonard, Enemy of Rome, Evans Bros, 1965, ISBN 0-237-44320-1 Cite error: The named reference "cottrell" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Lazenby, J.F., Hannibal's War, London, 1978

- ^ Caven, B., Punic Wars, London, George Werdenfeld and Nicholson Ltd., 1980

- ^ a b c d e Gowen, Hilary. "Hannibal Barca and the Punic Wars". Retrieved march 25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Daly, Gregory, Cannae: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War, London, England, Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-26147-3

- ^ a b c d Dodge, Theodore, Hannibal, Cambridge, Massachusetts, De Capo Press, 1891, ISBN 0-306-81362-9 Cite error: The named reference "dodge" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Moreman, Douglas. "Cannae - a Deception that Keeps on Deceiving". Retrieved march 25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Bradford, E., Hannibal, London, Macmillan London Ltd, 1981

- ^ a b c Healy, Mark, Cannae: Hannibal Smashes Rome's Army, Sterling Heights, Missouri, Osprey Publishing, 1994

- ^ a b Cowley, Robert (ed.), Parker, Geoffrey (ed.), The Reader’s Companion to Military History, "Battle of Cannae", Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996, ISBN 0-395-66969-3

- ^ Livius, Titus. "Livy's History of Rome: Book 22". The War with Hannibal: Books XXI–XXX of the History of Rome from its Foundation. Retrieved march 25.

{{cite web}}: Check|first=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Palmer, Robert EA (1997). Rome and Carthage at peace. Stuttgart, F. Steiner. ISBN 3-5150-7040-0.

- ^ Slip Knox, E. L. "The Punic Wars — Battle of Cannae". History of Western Civilization. Boise State University. Retrieved march 24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Livy, The History of Rome 22.51

- ^ Livy 23

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian, Cannae. London: Cassell & Co., 2001. 162-163.

- ^ Dodge, Theodore, Hannibal, Cambridge, Massachusetts, De Capo Press, 1891, ISBN 0-306-81362-9

- ^ "Appendix C" (PDF file —viewed as cached HTML—). The complete book of military science, abridged. Retrieved march 25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Carlton, James, The Military Quotation Book, New York City, New York, Thomas Dunne Books, 2002

- Dexter Hoyos, B., Hannibal: Rome's Greatest Enemy, Bristol Phoenix Press, 2005, ISBN 1-904675-46-8 (hbk) ISBN 1-904675-47-6 (pbk)

- Gregory Daly, Cannae: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War, Routledge, London/New York, 2002, ISBN 0-415-32743-1

- Delbrück, Hans, Warfare in Antiquity, 1920, ISBN 0-8032-9199-X

- Livy, Titus Livius and De Selincourt, Aubrey, The War with Hannibal: Books XXI-XXX of the History of Rome from its Foundation, Penguin Classics, Reprint edition, July 30 1965, ISBN 0-14-044145-X (pbk)

- Talbert, Richard J.A., ed., Atlas of Classical History, Routledge, London/New York, 1985, ISBN 0-415-03463-9

External links

- "The Battle of Cannae" at www.unrv.com

- "The Battle of Cannae" at Roman-empire.net

- "Rome and Carthage: Classic Battle Joined" - article by Greg Yocherer from Military History Magazine

- Cannae - a treatise by General Fieldmarshal Count Alfred von Schlieffen