Saint Maurice

Saint Maurice (also Moritz, Morris, or Mauritius) was the leader of the legendary Roman Theban Legion in the 3rd century, and one of the favorite and most widely venerated saints of that group. He was the patron saint of several professions, locales, and kingdoms.

Legend

According to the hagiographical material the legion, entirely composed of Christians, had been called from Thebes in Egypt to Gaul to assist Maximian to defeat a revolt by the Bagandæ.[3] However, when Maximian ordered them to harass some local Christians, they refused and Maximian ordered the unit punished. Every tenth soldier was killed, a military punishment known as decimation. More orders followed, they still refused, due in part to encouragement from Maurice, and a second decimation was ordered. In response to their refusal to use violence against fellow Christians, Maximian ordered all the remaining members of the 6,600 unit executed. The place in Switzerland where this occurred, known as Agaunum, is now Saint Maurice-en-Valais, site of the Abbey of Saint Maurice-en-Valais.

So reads the earliest account of their martyrdom, according to the public letter Eucherius, bishop of Lyon (c. 434–450), addressed to his fellow bishop Salvius. Alternate versions have the legion refusing Maximian's orders only after discovering a town they had just destroyed had been inhabited by innocent Christians, or that the emperor had them executed when they refused to sacrifice to the Roman gods.

Details of this story rest on tenuous historical grounds: for example, decimation had not been used to discipline a Roman legion for centuries: the previous documented execution of this sentence was in the reign of Galba, who ordered this done to a formation of marines that Nero had formed into a legion, and who demanded an eagle and standards. Further, Christians commonly refused to serve in the military, and the military staunchly followed Isis or Mithras (Sol Invictus), until Constantine's time at the earliest, making it unlikely they filled an entire legion.

Some historians[who?] suggest that this was a pious fabrication by Theodore, bishop of Octodurum, sometime between 388 and 394, whom Eucherius, bishop of Lyon, cites as his source of this story, to encourage his contemporary Christians serving in the Roman army to ignore the orders of their pagan superiors and instead side with the Christians. If it was a later fabrication, by Eucherius himself, its dissemination was certainly successful in drawing pilgrims to the abbey at Aguanum. That institution was created ex nihilo from 515 onwards by Sigismund, the first Catholic king of the Burgundians. The abbey was unique in its time as the creation of a king working in concord with bishops, rather than an organic development that occurred round the central figure of a holy monk. The new abbey was without doubt in need of a strong founding legend.

When Bertran de la Farge (in La Croix occitane) located the original Occitan cross somewhere in the marquisate of Provence, probably Venasque. He argued it could be a mixture of the Constantinople cross and the Coptic cross [1], which was brought to Provence by monks and maybe also through Saint Maurice.

Veneration

Saint Maurice became a patron saint of the Holy Roman Emperors. In 926, Henry I (919–936), even ceded the present Swiss canton of Aargau to the abbey, in return for Maurice's lance, sword and spurs. The sword and spurs of Saint Maurice was part of the regalia used at coronations of the Austro-Hungarian Emperors until 1916, and among the most important insignia of the imperial throne. In addition, some of the emperors were anointed before the Altar of Saint Maurice at St. Peter's Basilica. [2] In 929 Henry I the Fowler held a royal court gathering (Reichsversammlung) at Magdeburg. At the same time the Mauritius Kloster in honor of Maurice was founded. In 961, Otto I was building and enriching the cathedral at Magdeburg, which he intended for his own tomb. To that end,

- in the year 961 of the Incarnation and in the twenty-fifth year of his reign, in the presence of all of the nobility, on the vigil of Christmas, the body of St. Maurice was conveyed to him at Regensburg along with the bodies of some of the saint's companions and portions of other saints. Having been sent to Magdeburg, these relics were received with great honour by a gathering of the entire populace of the city and of their fellow countrymen. They are still venerated there, to the salvation of the homeland. [4]

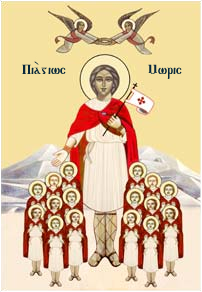

Maurice is traditionally depicted in full armor, in Italy emblasoned with a red cross. In folk culture he has become connected with the legend of the Spear of Destiny, which he is supposed to have carried into battle; his name is engraved on the Holy Lance of Vienna, one of several relics claimed as the spear that pierced Jesus' side on the cross. Saint Maurice gives his name to the town St. Moritz as well as to numerous places called Saint-Maurice in French speaking countries. The Indian Ocean island state of Mauritius was named after Maurice of Nassau, a member of the House of Orange, and not directly after St. Mauritius himself.

Over 650 religious foundations dedicated to Saint Maurice can be found in France and other European countries. In Switzerland alone, 7 churches or altars in Aargau, 6 in the Canton of Lucerne, 4 in the Canton of Solothurn, and 1 in Appenzell Innerrhoden can be found. In fact, his feast day in a cantonal holiday in Appenzell Innerrhoden.[2]Particularly notable among these are the Church and Abbey of Saint-Maurice-en-Valais, the Church of Saint Moritz in the Engadin, and the Monastery Chapel of Einsiedeln Abbey, where his name continues to be greatly revered. Several chivalric orders were established in his honor as well, including the Order of the Golden Fleece and the Order of Saint Maurice.[2] Additionally, fifty-two towns and villages in France have been named in his honor.[5]

Maurice is also the patron saint of a Roman Catholic parish and church in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans, and including part of the town of Arabi in St. Bernard parish.. The church was constructed in 1856, making it one of the oldest currently used churches in the area.

Ethnicity

The oldest available image of Saint Maurice at the Cathedral of Magdeburg which began construction in 937 A.D. is an image in which Maurice is depicted as a black man. It is this image that's displayed next to the grave of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor. The Cathedral of Magdeburg is the first and oldest standing temple honoring the life of St. Maurice.

St. Maurice is sometimes represented as a black Moor, which is actually the meaning of his name.[citation needed] According to Jean Devisse, a historian, it was not until 1240 that St. Maurice appeared as a black man; prior to that, Devisse says he had been depicted as a white man.[6][7] Because of this discrepancy, Maurice is depicted as possessing characteristics of both ethnic groups.

There is evidence to indicate that Maurice was Egyptian. The Coptic Greek name "Maurikios" appears in the papyri and is identical with the later Roman name "Mauritius", according to G. Heuser in his Personennamen der Kopten. Other parties have suggested that the name may be derived from the name of Lake Moeris.

In fact, the name is found in epitaths of the Ptolemaic Egypt and Egyptian Christian periods, and is still used as a personal name in Egypt's Coptic community.[2]

Gallery

-

Statue of Saint Maurice from the Magdeburg Cathedral.

-

18th century Baroque sculpture of Saint Maurice on the Holy Trinity Column in Olomouc, which was a part of the Austrian Empire in that time, now the Czech Republic.

-

"The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice" by El Greco. 1580-82

-

A statue of Saint Maurice, located in Soultz Haut-Rhin, France.

-

"The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice" by Romulo Cincinato. 1583. Oil on canvas, 540 x 288 cm, Monasterio de San Lorenzo, El Escorial, Spain. Cincinnato placed stronger emphasis on the execution scene, which has been brought into the foreground.

-

Jean Hey. "Portrait of Francis de Chateaubriand Presented by St. Maurice. c. 1500". Tempera on wood. Glasgow Museums and Art Galleries, Glasgow, UK.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Catholic Forum

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Atiya, Azia S., ed. The Coptic Encyclopedia, volume 5, p. 1572. New York, Macmillan Publishing Company, 1991. ISBN 0-02-897034-9.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Thietmar of Merseburg (2001). Ottonian Germany: The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg. David A. Warner (tr., ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. p. 104. ISBN 0719049253.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Butler's Lives of the Saints, New Full Edition, September, p.206. Collegeville, MN:The Liturgical Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8146-2385-9.

- ^ Hampton, Grace (1981). "[Review] The Image of the Black in Western Art, Volume II". The Journal of Negro History. 66 (1): 51–55. doi:10.2307/2716883.

- ^ Selzer, Linda Furgerson (1999). "Reading the painterly text: Clarence Major's 'The Slave Trade: View from the Middle Passage". African American Review. 33: 209–229. ISSN 1062-4783. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

{{cite journal}}: Text "issue 2" ignored (help)

External links

- On the image of the Blackamoor in European Heraldry - St. Maurice

- David Wood, "The Origin of the Cult of St. Maurice"

- Saint Maurice from the Golden Legend

- [2] - Coptic Orthodox Church Network, "Saint

Maurice of Theba"