Mac operating systems

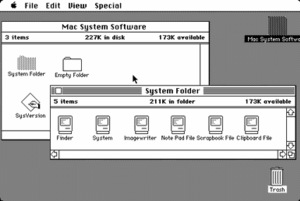

-->Mac OS is the trademarked name for a series of graphical user interface-based operating systems developed by Apple Inc. (formerly Apple Computer, Inc.) for their Macintosh line of computer systems. The Macintosh user experience is credited with popularizing the graphical user interface. The original form of what Apple would later name the "Mac OS" was the integral and unnamed system software first introduced in 1984 with the original Macintosh, usually referred to simply as the System software.

Apple deliberately downplayed the existence of the operating system in the early years of the Macintosh to help make the machine appear more user-friendly and to distance it from other operating systems such as MS-DOS, which were portrayed as arcane and technically challenging. Much of this early system software was held in ROM, with updates typically provided free of charge by Apple dealers on floppy disk. As increasing disk storage capacity and performance gradually eliminated the need for fixing much of an advanced GUI operating system in ROM, Apple explored cloning while positioning major operating system upgrades as separate revenue-generating products, first with System 7 and System 7.5, then with Mac OS 7.6 in 1997.

Earlier versions of the Mac OS were compatible only with Motorola 68000-based Macintoshes. As Apple introduced computers with PowerPC hardware, the OS was upgraded to support this architecture as well. Mac OS X, which has superseded the "Classic" Mac OS, is compatible with both PowerPC and Intel processors.

Versions

The early Macintosh operating system initially consisted of two pieces of software, called "System" and "Finder", each with its own version number.[1] System 7.5.1 was the first to include the Mac OS logo (a variation on the original "Happy Mac" smiley face Finder startup icon), and Mac OS 7.6 was the first to be named "Mac OS" (to ensure that users would still identify it with Apple, even when used in "clones" from other companies).

Until the advent of the later PowerPC G3-based systems, significant parts of the system were stored in physical ROM on the motherboard. The initial purpose of this was to avoid using up the limited storage of floppy disks on system support, given that the early Macs had no hard disk. (Only one model of Mac was ever actually bootable using the ROM alone, the 1991 Mac Classic model.) This architecture also allowed for a completely graphical OS interface at the lowest level without the need for a text-only console or command-line mode. A fatal software error, or even a low-level hardware error discovered during system startup (such as finding no functioning disk drives), was communicated to the user graphically using some combination of icons, alert box windows, buttons, a mouse pointer, and the distinctive Chicago bitmap font. Mac OS depended on this core system software in ROM on the motherboard, a fact which later helped to ensure that only Apple computers or licensed clones (with the copyright-protected ROMs from Apple) could run Mac OS.

The Mac OS can be divided into two families of operating systems:

- "Classic" Mac OS, the system which shipped with the first Macintosh in 1984 and its descendants, culminating with Mac OS 9.

- The newer Mac OS X (the "X" refers to the Roman numeral, ten). Mac OS X incorporates elements of OpenStep (thus also BSD Unix and Mach) and Mac OS 9. Its low-level BSD-based foundation, Darwin, is free software/open source software.

"Classic" Mac OS (1984-2001)

The "classic" Mac OS is characterized by its total lack of a command line; it is a completely graphical operating system. Heralded for its ease of use, it is also criticized for its cooperative multitasking, very limited memory management, lack of protected memory, and susceptibility to conflicts among operating system "extensions" that provide additional functionality (such as networking) or support for a particular device. Some extensions may not work properly together, or work only when loaded in a particular order. Troubleshooting Mac OS extensions can be a time-consuming process of trial and error.

The Macintosh originally used the Macintosh File System (MFS), a flat file system with only one level of folders. This was replaced by the Hierarchical File System (HFS), which had a true directory tree. Both file systems are otherwise compatible.

Most file systems used with DOS, Unix, or other operating systems treat a file as simply a sequence of bytes, requiring an application to know which bytes represented what type of information. By contrast, MFS and HFS gave files two different "forks". The data fork contained the same sort of information as other file systems, such as the text of a document or the bitmaps of an image file. The resource fork contained other structured data such as menu definitions, graphics, sounds, or code segments. A file might consist only of resources with an empty data fork, or only a data fork with no resource fork. A text file could contain its text in the data fork and styling information in the resource fork, so that an application which didn't recognize the styling information could still read the raw text. On the other hand, these forks provided a challenge to interoperability with other operating systems; copying a file from a Mac to a non-Mac system would strip it of its resource fork.

The Classic OS is still supported and Classic Applications Support was shipped in addition to OS X with PowerPC (but not Intel) Macs until early 2006. However, Intel-based Macintoshes cannot run the Classic system or applications, nor can PowerPC models that have been upgraded to Mac OS 10.5 Leopard.

Mac OS X (2000-present)

Mac OS X brought Unix-style memory management and pre-emptive multitasking to the Mac platform. It is based on the Mach kernel and the BSD implementation of UNIX, which were incorporated into NeXTSTEP, the object-oriented operating system developed by Steve Jobs's NeXT company. The new memory management system allowed more programs to run at once and virtually eliminated the possibility of one program crashing another. It is also the second Macintosh operating system to include a command line (the first is the now-discontinued A/UX, which supported classic Mac OS applications on top of a UNIX kernel), although it is never seen unless the user launches a terminal emulator.

However, since these new features put higher demands on system resources, Mac OS X only officially supported the PowerPC G3 and newer processors, and now has even higher requirements (the additional requirement of built-in USB (10.3) and later FireWire (10.4)). Even then, it runs somewhat slowly on older G3 systems for many purposes.

As of 2005, every update to Mac OS X since the original public beta has had the atypical quality of being perceptibly more responsive than the version it replaced, the opposite to the trend of most operating systems.

For over three years now, Mac OS X has gotten faster with every release — and not just "faster in the experience of most end users", but faster on the same hardware. This trend is unheard of among contemporary desktop operating systems.[2]

PowerPC builds of Mac OS X include a compatibility layer for running older Mac applications, the Classic Environment. This runs a full copy of the older Mac OS, version 9.1 or later, in a Mac OS X process. PowerPC-based Macs ship with OS 9.2 as well as OS X. OS 9.2 must be installed by the user — it is not installed by default on all new hardware revisions released after the release of Mac OS X 10.4. Most well-written "classic" applications function properly under this environment, but compatibility is only assured if the software was written to be unaware of the actual hardware, and to interact solely with the operating system. The Classic Environment is not available on Intel-based Macintoshes due to the incompatibility of Mac OS 9 with the x86 hardware, and was removed completely on Mac OS X 10.5.

Users of the original Mac OS generally upgraded to Mac OS X, but a few criticized it as being more difficult and less user-friendly than the original Mac OS, for the lack of certain features that had not been re-implemented in the new OS, or for being slower on the same hardware (especially older hardware), or other, sometimes serious incompatibilities with the older OS. Because drivers (for printers, scanners, tablets, etc.) written for the older Mac OS are not compatible with Mac OS X, and due to the lack of OS X support for older Apple machines, a significant number of Macintosh users have continued using the older OS. By 2005, it is reported that almost all users of systems capable of running Mac OS X are doing so, with only a small percentage still running the classic Mac OS.

In June 2005, Steve Jobs announced at his Worldwide Developers Conference keynote that Apple computers would be transitioning from PowerPC to Intel processors. At the same conference, Jobs announced Developer Transition Kits that included beta versions of Apple software including Mac OS X that developers could use to test their applications as they ported them to run on Intel-powered Macs. In January 2006, Apple released the first Macintosh computers with Intel processors, an iMac and the MacBook Pro, and in February 2006, Apple released a Mac Mini with an Intel Core Solo and Duo processor. On May 16, 2006, Apple released the MacBook, before completing the Intel transition on August 7 with the Mac Pro. To ease the transition for early buyers of the new machines, Intel-based Macs include an emulation technology called Rosetta, which allows them to run (at reduced speed) pre-existing Mac OS X native application software which was compiled only for PowerPC-based Macintoshes.

Project Star Trek

One interesting historical aspect of the classic Mac OS was a relatively unknown secret prototype Apple started work on in 1992, code-named "Project Star Trek". The goal of this project was to create a version of Mac OS that would run on Intel-compatible x86 personal computers. The intention was to release it in partnership with Novell, who would provide DOS compatibility, to support existing DOS applications on the platform. At that time, Novell DOS was losing market share to customers upgrading to Windows. A Mac OS and Novell DOS combination was considered a possible alternative. The project was short lived, being canceled only one year later in early 1993, when Apple's new CEO changed strategies. The team was able to get the Macintosh Finder and some basic applications, like QuickTime, running smoothly on a PC. Some of the code from this effort was reused when porting the Mac OS later to PowerPC.[3]

Fifteen years after Project Star Trek support for the x86 architecture was officially included in Mac OS, and then Apple transitioned all desktop computers to the x86 architecture. This was not the direct result of earlier Project Star Trek efforts. The Darwin underpinning used for Mac OS X 10.0 and later included support for the x86 architecture. The remaining non-Darwin portion of the Mac OS was released officially with the introduction of x86 Macintosh computers.

68000 emulation

Although the Star Trek software was never released, third-party Macintosh emulators, such as vMac, Basilisk II, and Executor, eventually made it possible to run the classic Mac OS on Intel-based PCs. These emulators were restricted to emulating the 68000 series of processors, and as such most couldn't run versions of the Mac OS that succeeded 8.1, which required PowerPC processors. Most also required a Mac ROM image or a hardware interface supporting a real Mac ROM chip; those requiring an image are of dubious legal standing as the ROM image may infringe on Apple's intellectual property.

A notable exception was the Executor commercial software product from Abacus Research & Development, the only product that exclusively used 100% reverse engineered code without the use of Apple technology. It ran extremely fast but never achieved more than a minor subset of functionality. Few programs were completely compatible and many were extremely crash-prone if they ran at all. Executor filled a niche market for porting 68000 classic Mac applications to x86 platforms; development ceased in 2002 and the project is now defunct.

Emulators using Mac ROM images offered near complete Mac OS compatibility and later versions offered excellent performance as modern x86 processor performance increased exponentially.

Unfortunately most of the Mac user base had already started moving to the PowerPC platform which offered excellent classic Mac backward compatibility on 8.xx & 9.xx operating systems along with faster PowerPC software support. This helped ease the transition to PowerPC-only applications while prematurely obsolescing 68000 emulators and the Classic-only applications they supported well before these emulators were refined enough to compete with a real Mac.

PowerPC emulation

At the time of 68000 emulator development PowerPC support was difficult to justify not only due to the emulation code itself but also the anticipated wide performance overhead of an emulated PowerPC architecture vs. a real PowerPC based Mac. This would later prove correct with the start of the PearPC project even years later despite the availability of 7th & 8th generation x86 processors employing similar architecture paradigms present in the PowerPC. Many application developers were also creating and releasing both 68000 Classic and PowerPC versions concurrently helping to negate the need for PowerPC emulation. PowerPC Mac users who could technically run either obviously chose the faster PowerPC applications. Soon Apple was no longer selling 68000 based Macs and the existing installed base started to quickly evaporate. Despite the eventual excellent 68000 emulation technology available they proved never to be even a minor threat to real Macs due to their late arrival and immaturity even several years after the release of much more compelling PowerPC based Macs.

The PearPC emulator is capable of emulating the PowerPC processors required by newer versions of the Mac OS (like Mac OS X). Unfortunately, it is still in the early stages and, like many emulators, tends to run much slower than a native operating system would.

During the its transition from PowerPC to Intel processors, Apple realized the need to incorporate a PowerPC emulator into Mac OS X in order to protect its customers' investments in software designed to run on the PowerPC. Apple's solution is an emulator called Rosetta. Prior to the announcement of Rosetta, industry observers assumed that any PowerPC emulator running on an x86 processor would suffer a heavy performance penalty (e.g., PearPC's slow performance). Rosetta's relatively minor performance penalty therefore took many by surprise.

Another PowerPC emulator is SheepShaver, which has been around since 1998 for BeOS on the PowerPC platform, but in 2002 was open sourced with porting efforts beginning to get it to run on other platforms. Originally it was not designed for use on x86 platforms and required an actual PowerPC processor present in the machine it was running on similar to a hypervisor. Although it provides PowerPC processor support, it can only run up to Mac OS 9.0.4 because it does not emulate a memory management unit.

Other examples include ShapeShifter (by the same programmer that conceived SheepShaver), Fusion and iFusion. The latter ran classic Mac OS with a PowerPC "coprocessor" accelerator card. Using this method has been said to equal or better the speed of a Macintosh with the same processor, especially with respect to the m68k series due to real Macs running in MMU trap mode, hampering performance.

Macintosh clones

Several computer manufacturers over the years have made Macintosh clones capable of running Mac OS, notably Power Computing, UMAX and Motorola. These machines normally ran various versions of classic Mac OS. Steve Jobs ended the clone licensing program after returning to Apple in 1997.

A/UX

In 1988, Apple released its first UNIX-based OS, A/UX, which was a UNIX operating system with the Mac OS look and feel. It was not very competitive for its time, due in part to the crowded Unix market. A/UX had most of its success in sales to the U.S. government, where UNIX was a requirement that Mac OS could not meet.

Graphical timeline

| Timeline of Mac operating systems |

|---|

|

References

Hormby, Tom (2005) "Star Trek: Apple's First Mac OS on Intel Project"

External links

- Mac OS X – Official site

- Mac 101 – Apple's introductory guide the Mac OS.

- Folklore.org – A site of anecdotes shared by the creators of the first Macintosh.

- History of Mac OS – Chronicle of version to version changes from the first release to version 10.4

- The Vintage Mac Museum: – Old Mac System - From System1 to System7