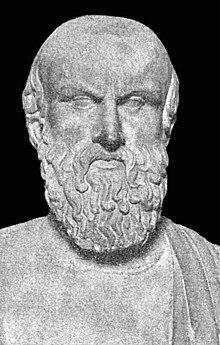

Aeschylus

Aeschylus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 525 BC/524 BC |

| Died | c. 456 BC |

| Occupation(s) | Playwright and Soldier |

Aeschylus (Template:PronEng or /ˈiːskɨləs/, Greek: Αἰσχύλος, 525 BC/524 BC – 456 BC/455 BC) was an ancient Greek playwright. He is often recognized as the father or the founder of tragedy,[1][2] and is the earliest of the three Greek tragedians whose plays survive, the others being Sophocles and Euripides. He expanded the number of characters in plays to allow for conflict among them; previously, characters interacted only with the chorus. No more than seven of the estimated seventy plays written by Aeschylus have survived into modern times.

Many of Aeschylus' works were influenced by the Persian invasion of Greece, which took place during his lifetime. His play The Persians remains a quintessential primary source of information about this period in Greek history. The war was so important to Greeks and to Aeschylus himself that, upon his death around 456 BC, his epitaph included a reference to his participation in the Greek victory at Marathon but not to his success as a playwright.

Life

Aeschylus was born in either 525 or 524 BC[3] in Eleusis, a small town about 27 kilometers northwest of Athens, which is nestled in the fertile valleys of western Attica.[4] His family was both wealthy and well-established; his father Euphorion was a member of the Eupatridae, the ancient nobility of Attica.[5] As a youth, he worked at a vineyard until, according to the 2nd-century AD geographer Pausanias, the god Dionysus visited him in his sleep and commanded him to turn his attention to the nascent art of tragedy.[5] As soon as he woke from the dream, the young Aeschylus began writing a tragedy, and his first performance took place in 499 BC, when he was only 26 years old.[5][4] After fifteen years, his skill was great enough to win a prize for his plays at Athens' annual city Dionysia playwriting competition.[5][6] But in the interim, his dramatic career was interrupted by war. The armies of the Persian Empire, which had already conquered the Greek city-states of Ionia, entered mainland Greece in the hopes of conquering it as well.

In 490 BC, Aeschylus and his brother Cynegeirus fought to defend Athens against Darius' invading Persian army at the Battle of Marathon.[4] The Athenians, though outnumbered, encircled and slaughtered the Persian army. This pivotal defeat ended the first Persian invasion of Greece proper and was celebrated across the city-states of Greece.[4] Though Athens was victorious, Cynegeirus died in the battle.[4] Aeschylus continued to write plays during the lull between the first and second Persian invasions of Greece, and won his first victory at the city Dionysia in 484 BC.[4] In 480 he was called into military service again, this time against Xerxes' invading forces at the Battle of Salamis.[4] This naval battle holds a prominent place in The Persians, his oldest surviving play, which was performed in 472 BC and won first prize at the Dionysia.[7]

Aeschylus was one of many Greeks who had been initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries, a cult to Demeter based in his hometown of Eleusis.[8] As the name implies, members of the cult were supposed to have gained some sort of mystical, secret knowledge. Firm details of the Mysteries' specific rites are sparse, as members were sworn under the penalty of death not to reveal anything about the Mysteries to non-initiates. Nevertheless, according to Aristotle[9] it was alleged that Aeschylus had placed clues about the secret rites into one of his plays. According to some sources, an angry mob tried to kill Aeschylus on the spot, but he fled the scene. When he stood trial for his offense, Aeschylus pleaded ignorance and was only spared because of his brave service in the Persian Wars.

Aeschylus traveled to Sicily once or twice in the 470s BC, having been invited by Hieron, tyrant of Syracuse, a major Greek city on the eastern side of the island.[4] By 473 BC, after the death of Phrynichus, one of his chief rivals, Aeschylus was the yearly favorite in the Dionysia, winning first prize in nearly every competition.[4] In 458 BC, he returned to Sicily for the last time, visiting the city of Gela where he died in 456 or 455 BC. As legend has it, an eagle, mistaking the playwright's bald crown for a stone, dropped a tortoise on his head (though some accounts differ, claiming it was a stone dropped by an eagle or vulture that mistook his bald head for the egg of a flightless bird).[4] This incident may not be as unlikely as it seems, as the Lammergeier is native to the Mediterranean region – a large eagle-like vulture known to drop bones and tortoises on rocks to break them open. Aeschylus would continue to be honored by the Athenians, who respected his work so highly that they allowed other playwrights to reproduce his plays as part of the Dionysia rather than presenting original works of their own.[4] His sons Euphorion and Euæon and his nephew Philocles would follow in his footsteps and become playwrights themselves.[4]

The inscription on Aeschylus' gravestone makes no mention of his theatrical renown, commemorating only his military achievements:

| Greek | English |

|

|

Works

The Greek art of the drama had its roots in religious festivals for the gods, chiefly Dionysus, the god of wine.[6] During Aeschylus' lifetime, dramatic competitions became part of the City Dionysia in the spring.[6] The festival began with an opening procession, continued with a competition of boys singing dithyrambs, and culminated in a pair of dramatic competitions.[11] The first competition, which Aeschylus would have participated in, was for the tragedians, and consisted of three playwrights each presenting three tragic plays followed by a shorter comedic satyr play.[11] A second competition of five comedic playwrights followed, and the winners of both competitions were chosen by a panel of judges.[11]

Aeschylus entered many of these competitions in his lifetime, and it is estimated that he wrote some 70 to 90 plays.[12] Only seven tragedies have survived intact: The Persians, Seven against Thebes, The Suppliants, the trilogy known as The Oresteia, consisting of the three tragedies Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers and The Eumenides, and Prometheus Bound (whose authorship is disputed). With the exception of this last play -- the success of which is uncertain -- all of Aeschylus' extant tragedies are known to have won first prize at the City Dionysia. The Alexandrian Life of Aeschylus indicates that the playwright took the first prize at the City Dionysia thirteen times. This compares favorably with Sophocles' reported eighteen victories (with a substantially larger catalogue, at an estimated 120 plays), and dwarfs the five victories of Euripides (who featured a catalogue of roughly 90 plays).

One hallmark of Aeschylean dramaturgy appears to have been his tendency to write connected trilogies in which each play serves as a chapter in a continuous dramatic narrative.[13] The Oresteia is the only wholly extant example of this type of connected trilogy, but there is ample evidence that Aeschylus wrote such trilogies often. The comic satyr plays that would follow his dramatic trilogies often treated a related mythic topic. For example, the Oresteia's satyr play Proteus treated the story of Menelaus's detour in Egypt on his way home from the Trojan War. Based on the evidence provided by a catalogue of Aeschylean play titles, scholia, and play fragments recorded by later authors, it is assumed that three other of Aeschylus' extant plays were components of connected trilogies: Seven against Thebes being the final play in an Oedipus trilogy, and The Suppliants and Prometheus Bound each being the first play in a Danaid trilogy and Prometheus trilogy, respectively (see below). Scholars have moreover suggested several completely lost trilogies derived from known play titles. A number of these trilogies treated myths surrounding the Trojan War. One -- collectively called the Achilleis and comprising the titles Myrmidons, Nereids and Phrygians (alternately, The Ransoming of Hector) -- recounts Hector's death at the hands of Achilles and the subsequent holding of Hector's body for ransom; another trilogy apparently recounts the entry of the Trojan ally Memnon into the war, and his death at the hands of Achilles (Memnon and The Weighing of Souls being two components of the trilogy); The Award of the Arms, The Phrygian Women, and The Salaminian Women suggest a trilogy about the madness and subsequent suicide of the Greek hero Ajax; Aeschylus also seems to have treated Odysseus' return to Ithaca after the war (including his killing of his wife Penelope's suitors and its consequences) with a trilogy consisting of The Soul-raisers, Penelope and The Bone-gatherers. Other suggested trilogies touched on the myth of Jason and the Argonauts (Argô, Lemnian Women, Hypsipylê); the life of Perseus (The Net-draggers, Polydektês, Phorkides); the birth and exploits of Dionysus (Semele, Bacchae, Pentheus); and the aftermath of the war portrayed in Seven against Thebes (Eleusinians, Argives (or Argive Women), Sons of the Seven).

The Persians

The earliest of the plays that still exist is The Persians (Persai), performed in 472 BC and based on experiences in Aeschylus' own life, specifically the Battle of Salamis.[14] It is unique among Greek tragedies in treating a recent historical event rather than a heroic or divine myth.[1] The Persians focuses on the popular Greek theme of hubris by blaming Persia's loss on the overwhelming pride of its king.[14] It opens with the arrival of a messenger in Susa, the Persian capital, bearing news of the catastrophic Persian defeat at Salamis to Atossa, the mother of the Persian King Xerxes. Atossa then travels to the tomb of Darius, her husband, where his ghost appears to explain the cause of the defeat. It is, he says, the result of Xerxes' hubris in building a bridge across the Hellespont, an action which angered the gods. Xerxes appears at the end of the play, not realizing the cause of his defeat, and the play closes to lamentations by Xerxes and the chorus.[15]

Seven against Thebes

Seven against Thebes (Hepta epi Thebas), which was performed in 467 BC, picks up a contrasting theme, that of fate and the interference of the gods in human affairs.[14] It also marks the first known appearance in Aeschylus' work of a theme which would continue through his plays, that of the polis (the city) being a vital development of human civilization.[16] The play tells the story of Eteocles and Polynices, the sons of the shamed King of Thebes, Oedipus. The sons agree to alternate in the throne of the city, but after the first year Eteocles refuses to step down, and Polynices wages war to claim his crown. The brothers go on to kill each other in single combat, and the original ending of the play consisted of lamentations for the dead brothers. A new ending was added to the play some fifty years later: Antigone and Ismene mourn their dead brothers, a messenger enters announcing an edict prohibiting the burial of Polynices; and finally, Antigone declares her intention to defy this edict. The play was the third in a connected Oedipus trilogy; the first two plays were Laius and Oedipus, likely treating those elements of the Oedipus myth detailed most famously in Sophocles' Oedipus the King. The concluding satyr play was The Sphinx.

The Suppliants

Aeschylus would continue his emphasis on the polis with The Suppliants in 463 BC (Hiketides), which pays tribute to the democratic undercurrents running through Athens in advance of the establishment of a democratic government in 461. In the play, the Danaids, the fifty daughters of Danaus, founder of Argos, flee a forced marriage to their cousins in Egypt. They turn to King Pelasgus of Argos for protection, but Pelasgus refuses until the people of Argos weigh in on the decision, a distinctly democratic move on the part of the king. The people decide that the Danaids deserve protection, and they are allowed within the walls of Argos despite Egyptian protests.[17] The 1952 publication of Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 2256 fr. 3 confirmed a long-assumed (because of The Suppliants' cliffhanger ending) Danaid trilogy, whose constituent plays are generally agreed to be The Suppliants, The Aegyptids and The Danaids. A plausible reconstruction of the trilogy's last two-thirds runs thus: In The Aegyptids, the Argive-Egyptian war threatened in the first play has transpired. During the course of the war, King Pelasgus has been killed, and Danaus comes to rule Argos. He negotiates a peace settlement with Aegyptus, as a condition of which, his fifty daughters will marry the fifty sons of Aegyptus. Danaus secretly informs his daughters of an oracle predicting that one of his sons-in-law would kill him; he therefore orders the Danaids to murder the Aegyptids on their wedding night. His daughters agree. The Danaids would open the day after the wedding. In short order, it is revealed that forty-nine of the Danaids killed their husbands as ordered; Hypermnestra, however, loved her husband Lynceus, and thus spared his life and helped him to escape. Angered by his daughter's disobedience, Danaus orders her imprisonment and, possibly, her execution. In the trilogy's climax and denouement, Lynceus reveals himself to Danaus, and kills him (thus fulfilling the oracle). He and Hypermnestra will establish a ruling dynasty in Argos. The other forty-nine Danaids are absolved of their murderous crime, and married off to unspecified Argive men. The satyr play following this trilogy was titled Amymone, after one of the Danaids.

The Oresteia

The most complete tetralogy of Aeschylus' work that still exists is the Oresteia (458 BC), of which only the satyr play is missing.[14] In fact, the Oresteia is the only full trilogy of Greek plays by any playwright that modern scholars have uncovered.[14] The trilogy consists of Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers (Choephoroi), and The Eumenides.[16] Together, these plays tell the bloody story of the family of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae.

Agamemnon

Agamemnon describes his death at the hands of his wife Clytemnestra, who was angry both at Agamemnon's sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia and at his keeping the Trojan prophetess Cassandra as a concubine. Cassandra enters the palace even though she knows she will be murdered by Clytemnestra as well, knowing that she cannot avoid her gruesome fate. The ending of the play includes a prediction of the return of Orestes, son of Agamemnon, who will surely avenge his father.[16]

The Libation Bearers

The Libation Bearers continues the tale, opening with Clytemnestra's account of a nightmare in which she gives birth to a snake. She orders Electra, her daughter, to pour libations on Agamemnon's tomb (with the assistance of libation bearers) in hope of making amends. At the tomb, Electra meets Orestes, who has returned from protective exile in Phocis, and they plan revenge upon Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus together. They enter the palace pretending to bear news of Orestes' death, and when Clytemnestra calls in Aegisthus to share in the news, Orestes kills them both. Immediately, Orestes is beset by the Furies, who avenge patricide and matricide in Greek mythology.[16]

The Eumenides

The final play of The Eumenides, addresses the question of Orestes' guilt.[16] The Furies pursue Orestes from Argos and into the wilderness. Orestes makes his way to the temple of Apollo and begs him to drive the Furies away. Apollo had encouraged Orestes to kill Clytemnestra, and so bears a portion of the guilt of the act. But the Furies belong to the older race of the Titans, and Apollo is unable to drive them away. He sends Orestes to the temple of Athena, with Hermes as a guide. There, the furies track him down and, just before he is to be killed, the goddess Athena, patron of Athens, steps in and declares that a trial is necessary. Apollo argues Orestes' case and, after the jury splits their vote, Athena decides against the Furies. She also renames them the Eumenides, or kindly ones, and declares that thereafter all future hung juries should result in acquittal, since mercy should take precedence over harshness. The Eumenides specifically extols the importance of reason in the development of laws, and, like The Suppliants, lauds the ideals of a democratic Athens.[17]

Prometheus Bound

In addition to these six works, a seventh tragedy, Prometheus Bound, is uniformly attributed to Aeschylus by ancient authorities. Since the late nineteenth century, however, modern scholarship has increasingly doubted this ascription largely on stylistic grounds. Its production date is also in dispute, with theories ranging from the 480's BC to as late as the 410's.[4][18] The play consists mostly of static dialogue, as throughout the play Prometheus is bound to a rock as punishment for providing fire to humans. The god Hephaestus, the Titan Oceanus, and the chorus of Oceanids all express sympathy for the Titan's plight. Prometheus meets Io, a fellow victim of Zeus' cruelty; he prophesies for her future travels, and reveals that one of her descendents will eventually free Prometheus. The play closes with Zeus sending Prometheus into the abyss because the Titan refuses to divulge the secret of a potential marriage that could be the Olympian's downfall.[15] The Prometheus Bound appears to have been the first play in a trilogy called the Prometheia. In the second play, Prometheus Unbound, Heracles frees Prometheus from his chains and kills the eagle that had been sent daily to eat the Titan's perpetually regenerating liver. Perhaps foreshadowing his eventual reconciliation with Prometheus, we learn that Zeus has released the other Titans whom he imprisoned at the conclusion of the Titanomachy. In the trilogy's conclusion, Prometheus the Fire-Bringer, the Titan finally warns Zeus not to lie with the sea nymph Thetis, for she is fated to give birth to a son greater than the father. Not wishing to be overthrown, Zeus marries Thetis off to the mortal Peleus; the product of that union will be Achilles, Greek hero of the Trojan War. After reconciling with Prometheus, Zeus perhaps inaugurates a festival in his honor at Athens.

Influence on Greek drama and culture

When Aeschylus first began writing, the theatre had only just begun to evolve, although earlier playwrights like Thespis had expanded the cast to include an actor who was able to interact with the chorus.[19] Aeschylus added a second actor, allowing for greater dramatic variety, while the chorus played a less important role.[19] He is sometimes credited with introducing skenographia, or scene-decoration, though Aristotle gives this distinction to Sophocles. Aeschylus is moreover said to have made innovations in costuming -- making the costumes more elaborate and dramatic, and having his actors wear platform boots (cothurni) to make them more visible to the audience. According to a later account of Aeschylus' life, as they walked on stage in the first performance of the Eumenides, the chorus of Furies were so frightening in appearance that they caused young children to faint and pregnant women to go into labor.

Overall, though, he continued to write within the very strict bounds of Greek drama: his plays were written in verse, no violence could be performed on stage, and the plays had to have a certain remoteness from daily life in Athens, either by relating stories about the gods or by being set, like The Persians, in far-away locales.[20] Aeschylus' work has a strong moral and religious emphasis.[20] The Oresteia trilogy particularly concentrated on man's position in the cosmos in relation to the gods, divine law, and divine punishment.[21] Aeschylus' abiding popularity is perhaps most evident in the praise the comic playwright Aristophanes gives him in The Frogs, produced some half-century after Aeschylus' death.

Influence outside of Greek Culture

Aeschylus' works were influential beyond his own time. Hugh Lloyd-Jones (Regius Professor of Greek Emeritus at Oxford University) wrote extensively on Wagner's relationship reverence of Aeschylus and the ensuing effect on his works. Michael Ewans agues in his Wagner and Aeschylus. The 'Ring' and the 'Orestia' (London: Faber. 1982) that the influence was so great as to merit a direct comparison, character by character, of Wagner's 'Ring' and Aeschylus' 'Orestia.' Reviews of his book, while not denying Lloyd-Jones' views that Wagner read and respected Aeschylus, refute Ewans' arguments on the grounds that they seem unreasonable and forced. [22]

Sir J. T. Sheppard, Provost of King's College in Cambridge, argues in the second half of his Aeschylus and Sophocles: their Work and Influence that Aeschylus, along with Sophocles, had a major part in the formation of dramatic literature from the Renaissance to the present, specifically in French and Elizabethan drama. He also claims that their influence went beyond just drama and applies to literature in general, citing Milton and the Romantics as his prime examples. [23]

See also

- Asteroid 2876 Aeschylus, which is named for him

Footnotes

- ^ a b Freeman: 243

- ^ P.W. Buckham: 121, quoting from Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature by August Wilhelm von Schlegel. "Aeschylus is to be considered as the creator of Tragedy: in full panoply she sprung from his head, like Pallas from the head of Jupiter. He clad her with dignity, and gave her an appropriate stage; he was the inventor of scenic pomp, and not only instructed the chorus in singing and dancing, but appeared himself as an actor. He was the first that expanded the dialogue, and set limits to the lyrical part of tragedy, which, however, still occupies too much space in his pieces."

- ^ The uncertainty is the result of the difference between the ancient Attic calendar and our own. Their year began around late June or early July of our calendar. Therefore, unless we know the exact month of an event's occurrence, we must assign it to an ambiguous date such as 525/524.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Sommerstein: 33

- ^ a b c d Bates: 53-59

- ^ a b c Freeman: 241

- ^ Sommerstein: 34

- ^ See Martin 2000, chapter 10.1.

- ^ In Ethics 3.2.

- ^ text from the Anthologiae Graecae Appendix, vol. 3, Epigramma sepulcrale, Page 17

- ^ a b c Freeman: 242

- ^ There is disagreement among scholars concerning the total number of plays. For example, Freeman (243) claims around 90 while Pomeroy et al. (222) claim 'perhaps seventy plays'.

- ^ For a good summary of Aeschylean trilogies, see Sommerstein 1996, a comprehensive study of the poet.

- ^ a b c d e Freeman: 244

- ^ a b Vellacott: 7-19

- ^ a b c d e Freeman: 244-246

- ^ a b Freeman: 246

- ^ According to Griffith (32), "Most modern scholars have seen no good reason to doubt the traditional ascription, though opinions as to date have varied." He adds that "we cannot hope for certainty one way or the other" (34).

- ^ a b Pomeroy: 222

- ^ a b Pomeroy: 223

- ^ Pomeroy: 224-225

- ^ Review author: Raymond Furness The Modern Language Review, Vol. 79, No. 1. (Jan., 1984), pp. 239-240. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0026-7937%28198401%2979%3A1%3C239%3AWAAT%27A%3E2.0.CO%3B2-6

- ^ Review of Aeschylus and Sophocles: their Work and Influence The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 47, Part 2. (1927), p. 265. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0075-4269%281927%2947%3C265%3AAASTWA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-L

References

- Bates, Alfred, ed. (1906). The Drama: Its History, Literature, and Influence on Civilization, Vol. 1. London: Historical Publishing Company.

- Buckham, P.W. (1827). The Theater of the Greeks, or the History, Literature, and Criticism of Grecian Drama. Cambridge: W.P. Grant.

- Freeman, Charles (1999). The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0670885150

- Griffith, Mark ed. (1983). Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521270111

- Martin, Thomas (2000). Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times. Yale University Press.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B., ET. AL. (1999). Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195097432

- Sommerstein, Alan H. (1996). Aeschylean Tragedy. Bari.

- -- (2002). Greek Drama and Dramatists. London: Routledge Press. ISBN 0415260272

- Thomson, George (1973) Aeschylus and Athens: A Study in the Social Origin of Drama. London: Lawrence and Wishart (4th edition)

- Vellacott, Philip, (1961). Prometheus Bound and Other Plays: Prometheus Bound, Seven Against Thebes, and The Persians. New York:Penguin Classics. ISBN 0140441123

Further reading

- Meagher, R. E. (1998). Aeschylus: Seven Against Thebes. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc. [1] ISBN 978-0-86516-337-9.

External links

- Wikipedia- Theatre of ancient Greece

- Selected Poems of Aeschylus

- Works by Aeschylus at Project Gutenberg

- Online English Translations of Aeschylus

- Photo of a fragment of The Net-pullers

- Prometheus Bound

- Crane, Gregory. "Aeschylus (4)". Perseus Encyclopedia.