Alhambra

- This article is about the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. For other meanings, see: Alhambra (disambiguation).

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, iv |

| Reference | 314 |

| Inscription | 1984 (8th Session) |

| Extensions | 1994 |

The Alhambra (Arabic: الحمراء = Al-Ħamrā; literally "the red") is a palace and fortress complex of the Moorish monarchs of Granada in southern Spain (known as Al-Andalus when the fortress was constructed), occupying a hilly terrace on the southeastern border of the city of Granada. 37°10′37″N 3°35′24″W / 37.17686°N 3.589901°W

Once the residence of the Muslim kings of Granada and their court, it is currently a museum exhibiting exquisite Islamic architecture. A Renaissance palace was also inserted by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

37°10′36.81″N 3°35′23.95″W / 37.1768917°N 3.5899861°W

Overview

The terrace or plateau where the Alhambra sits measures about 740 m (2430 ft) in length by 205 m (674 ft) at its greatest width. It extends from WNW to ESE and covers an area of about 142,000 m². It is enclosed by a strongly fortified wall, which is flanked by thirteen towers. The river Darro, which foams through a deep ravine on the north, divides the plateau from the Albaicín district of Granada; the Assabica valley, containing the Alhambra Park on the west and south, and, beyond this valley, the almost parallel ridge of Monte Mauror, separate it from the Antequeruela district.

History

Alhambra, signifying in Arabic "the red" (Al Hamra الحمراء), derives from the colour of the red clay of the surroundings of which the fort is made. The buildings of the Alhambra were originally whitewashed; however, the buildings now seen today are reddish. The first reference to the Qal’at al Hamra was during the battles between the Arabs and the Muladies during the rule of the ‘Abdullah ibn Muhammad (r. 888-912). In one particularly fierce and bloody skirmish, the Muladies soundly defeated the Arabs, who were then forced to take shelter in a primitive red castle located in the province of Elvira, presently located in Granada. According to surviving documents from the era, the red castle was quite small, and its walls were not capable of deterring an army intent on conquering. The castle was then largely ignored until the eleventh century, when its ruins were renovated and rebuilt by Samuel ibn Naghralla, vizier to the King Bādīs of the Zirid Dynasty, in an attempt to preserve the small Jewish settlement also located on the Sabikah hill. However, evidence from Arab texts indicates that the fortress was easily penetrated and that the actual Alhambra that survives today was built during the Nasrid Dynasty.

Ibn Nasr, the founder of the Nasrid Dynasty, was forced to flee to Granada in order to avoid persecution by King Ferdinand and his supporters during attempts to rid Spain of Moorish Dominion. After retreating to Granada, Ibn-Nasr took up residence at the Palace of Bādis in the Alhambra. A few months later, he embarked on the construction of a new Alhambra fit for the residence of a king. According to an Arab manuscript published as the Anónimo de Granada y Copenhague, "This year 1238 Abdallah ibn al-Ahmar climbed to the place called ‘the Alhambra inspected it, laid out the foundations of a castle and left someone in charge of its construction…" The design included plans for six palaces, five of which were grouped in the northeast quadrant forming a royal quarter, two circuit towers, and numerous bathhouses. During the reign of the Nasrid Dynasty, the Alhambra was transformed into a palatine city complete with an irrigation system composed of acequias for the lush and beautiful gardens of the Generalife located outside the fortress. Previously, the old Alhambra structure had been dependent upon rainwater collected from a cistern and from what could be brought up from the Albaicín. The creation of the Sultan's Canal solidified the identity of the Alhambra as a sumptuous palace-city rather than a defensive and ascetic structure.

Art of the Alhambra

The art within the rooms embodied the small remaining portion of Moorish dominion within Spain and ushered in the last great period of Andalusian art which had become isolated within the small sphere of Granada. Trapped without influence from the Islamic mainland, artists endlessly reproduced the same forms and trends, creating a new style characterized by its exquisite refinement and beauty perfected over the course of the Nasrid Dynasty. Elegant columns seem to soar effortlessly towards the sky, intricate muquarnas, stalactite-like ceiling decorations, create an airy appearance in several chambers, and the interiors of numerous palaces are decorated with elegant arabesques and graceful depictions of calligraphy. The splendid arabesques of the interior are ascribed, among other kings, to Yusef I, Mohammed V, and Ismail I. After the Christian conquest of the city in 1492 by Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, the conquerors began to alter the Alhambra. The open work was filled up with whitewash, the painting and gilding effaced, and the furniture soiled, torn or removed. Charles V (1516–1556) rebuilt portions in the Renaissance style of the period and destroyed the greater part of the winter palace to make room for a Renaissance-style structure which has never been completed. Philip V (1700–1746) italianised the rooms and completed his palace right in the middle of what had been the Moorish building. He ran up partitions which blocked up whole apartments. In subsequent centuries under Spanish authorities, Moorish art was further defaced; and in 1812, some of the towers were blown up by the French under Count Sebastiani, while the whole buildings narrowly escaped the same fate. Napoleon had tried to blow up the whole complex. Just before his plan was carried out, a soldier who secretly wanted the plan of Napoleon — his commander — to fail defused the explosives and thus saved the Alhambra for posterity. In 1821, an earthquake caused further damage. The work of restoration undertaken in 1828 by the architect José Contreras was endowed in 1830 by Ferdinand VII; and after the death of Contreras in 1847, it was continued with fair success by his son Rafael (d. 1890) and his grandson.

Setting

Moorish poets described it as "a pearl set in emeralds," in allusion to the brilliant colour of its buildings and the luxuriant woods around them. The park (Alameda de la Alhambra), which is overgrown with wildflowers and grass in the spring, was planted by the Moors with roses, oranges and myrtles; its most characteristic feature, however, is the dense wood of English elms brought thither in 1812 by the Duke of Wellington. The park is celebrated for the multitude of its nightingales and is usually filled with the sound of running water from several fountains and cascades. These are supplied through a conduit 8 km (5 miles) long, which is connected with the Darro at the monastery of Jesus del Valle, above Granada.

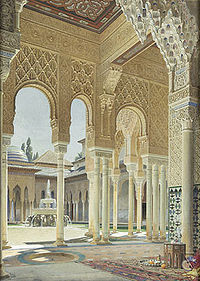

In spite of the long neglect, willful vandalism and sometimes ill-judged restoration which the Alhambra has endured, it remains the most perfect example of Moorish art in its final European development, freed from the direct Byzantine influences which can be traced in the Mezquita cathedral of Córdoba, more elaborate and fantastic than the Giralda at Seville. The majority of the palace buildings are, in ground-plan, quadrangular, with all the rooms opening on to a central court; and the whole reached its present size simply by the gradual addition of new quadrangles, designed on the same principle, though varying in dimensions, and connected with each other by smaller rooms and passages. In every case, the exterior is left plain and austere, as if the architect intended thus to heighten by contrast the splendour of the interior. Within, the palace is unsurpassed for the exquisite detail of its marble pillars and arches, its fretted ceilings and the veil-like transparency of its filigree work in stucco. Sun and wind are freely admitted, and the whole effect is one of the most airy lightness and grace. Blue, red, and a golden yellow, all somewhat faded through lapse of time and exposure, are the colours chiefly employed.

The decoration consists, as a rule, of stiff, conventional foliage, Arabic inscriptions, and geometrical patterns wrought into arabesques of almost incredible intricacy and ingenuity. Painted tiles are largely used as panelling for the walls.

A tour of the Alhambra

The Alhambra resembles many medieval Christian strongholds in its threefold arrangement as a castle, a palace and a residential annex for subordinates. The alcazaba or citadel, its oldest part, is built on the isolated and precipitous foreland which terminates the plateau on the northwest. That is all massive outer walls, towers and ramparts are left. On its watch-tower, the Torre de la Vela, 25 m (85 ft) high, the flag of Ferdinand and Isabella was first raised, in token of the Spanish conquest of Granada on January 2, 1492. A turret containing a huge bell was added in the 18th century and restored after being damaged by lightning in 1881. Beyond the Alcazaba is the palace of the Moorish kings, or Alhambra properly so-called; and beyond this, again, is the Alhambra Alta (Upper Alhambra), originally tenanted by officials and courtiers.

Access from the city to the Alhambra Park is afforded by the Puerta de las Granadas (Gate of Pomegranates), a massive triumphal arch dating from the 15th century. A steep ascent leads past the Pillar of Charles V, a fountain erected in 1554, to the main entrance of the Alhambra. This is the Puerta Judiciaria (Gate of Judgment), a massive horseshoe archway surmounted by a square tower and used by the Moors as an informal court of justice. The hand of Fatima, with fingers outstretched as a talisman against the evil eye, is carved above this gate on the exterior; a key, the symbol of authority, occupies the corresponding place on the interior. A narrow passage leads inward to the Plaza de los Aljibes (Place of the Cisterns), a broad open space which divides the Alcazaba from the Moorish palace. To the left of the passage rises the Torre del Vino (Wine Tower), built in 1345 and used in the 16th century as a cellar. On the right is the palace of Charles V, a cold-looking but majestic Renaissance building, out of harmony with its surroundings, which it tends somewhat to dwarf by its superior size.

The present entrance to the Palacio Árabe, or Casa Real (Moorish palace), is by a small door from which a corridor connects to the Patio de los Arrayanes (Court of the Myrtles), also called the Patio de la Alberca (Court of the Blessing or Court of the Pond), from the Arabic birka, "pool". This court is 42 m (140 ft) long by 22 m (74 ft) broad; and in the centre, there is a large pond set in the marble pavement, full of goldfish, and with myrtles growing along its sides. There are galleries on the north and south sides; that on the south is 7 m (27 ft) high and supported by a marble colonnade. Underneath it, to the right, was the principal entrance, and over it are three elegant windows with arches and miniature pillars. From this court, the walls of the Torre de Comares are seen rising over the roof to the north and reflected in the pond.

The Salón de los Embajadores (Hall of the Ambassadors) is the largest in the Alhambra and occupies all the Torre de Comares. It is a square room, the sides being 12 m (37 ft) in length, while the centre of the dome is 23 m (75 ft) high. This was the grand reception room, and the throne of the sultan was placed opposite the entrance. It was in this setting that Cristopher Columbus received Isabel and Ferdinand's support to sail to the New World. The tiles are nearly 4 ft (1.2 m) high all round, and the colours vary at intervals. Over them is a series of oval medallions with inscriptions, interwoven with flowers and leaves. There are nine windows, three on each facade, and the ceiling is admirably diversified with inlaid-work of white, blue and gold, in the shape of circles, crowns and stars—a kind of imitation of the vault of heaven. The walls are covered with varied stucco works of most delicate patterns, surrounding many ancient escutcheons.

The celebrated Patio de los Leones (Court of the Lions) is an oblong court, 116 ft (35 m) in length by 66 ft (20 m) in width, surrounded by a low gallery supported on 124 white marble columns. A pavilion projects into the court at each extremity, with filigree walls and light domed roof, elaborately ornamented. The square is paved with coloured tiles, and the colonnade with white marble; while the walls are covered 5 ft (1.5 m) up from the ground with blue and yellow tiles, with a border above and below enamelled blue and gold. The columns supporting the roof and gallery are irregularly placed, with a view to artistic effect; and the general form of the piers, arches and pillars is most graceful. They are adorned by varieties of foliage, etc.; about each arch there is a large square of arabesques; and over the pillars is another square of exquisite filigree work. In the centre of the court is the celebrated Fountain of Lions, a magnificent alabaster basin supported by the figures of twelve lions in white marble, not designed with sculptural accuracy, but as emblems of strength and courage.

The Sala de los Abencerrajes (Hall of the Abencerrages) derives its name from a legend according to which the father of Boabdil, last king of Granada, having invited the chiefs of that illustrious line to a banquet, massacred them here. This room is a perfect square, with a lofty dome and trellised windows at its base. The roof is exquisitely decorated in blue, brown, red and gold, and the columns supporting it spring out into the arch form in a remarkably beautiful manner. Opposite to this hall is the Sala de las dos Hermanas (Hall of the two Sisters), so-called from two very beautiful white marble slabs laid as part of the pavement. These slabs measure 50 by 22 cm (15 by 7½ in) and are without flaw or stain. There is a fountain in the middle of this hall, and the roof —a dome honeycombed with tiny cells, all different, and said to number 5000— is a magnificent example of the so-called "stalactite vaulting" of the Moors.

Among the other wonders of the Alhambra are the Sala de la Justicia (Hall of Justice), the Patio del Mexuar (Court of the Council Chamber), the Patio de Daraxa (Court of the Vestibule), and the Peinador de la Reina (Queen's Robing Room), in which are to be seen the same delicate and beautiful architecture and the same costly and elegant decorations. The palace and the Upper Alhambra also contain baths, ranges of bedrooms and summer-rooms, a whispering gallery and labyrinth, and vaulted sepulchres.

The original furniture of the palace is represented by the celebrated vase of the Alhambra, a splendid specimen of Moorish ceramic art, dating from 1320 and belonging to the first period of Moorish porcelain. It is 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) high; the ground is white, and the enamelling is blue, white and gold.

Of the outlying buildings in connection with the Alhambra, the foremost in interest is the Palacio de Generalife or Gineralife (the Muslim Jennat al Arif, "Garden of Arif," or "Garden of the Architect"). This villa probably dates from the end of the 13th century but has been restored several times. Its gardens, however, with their clipped hedges, grottos, fountains, and cypress avenues, are said to retain their original Moorish character. The Villa de los Martires (Martyrs' Villa), on the summit of Monte Mauror, commemorates by its name the Christian slaves who were forced to build the Alhambra and confined here in subterranean cells. The Torres Bermejas (Vermilion Towers), also on Monte Mauror, are a well-preserved Moorish fortification, with underground cisterns, stables, and accommodation for a garrison of 200 men. Several Roman tombs were discovered in 1829 and 1857 at the base of Monte Mauror.

Miscellaneous

The Alhambra, Generalife and Albayzín of Granada are listed as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO.

Influence of the Alhambra

Alhambra in literature

Parts of the following novels are set in the Alhambra:

- Washington Irving's Tales of the Alhambra. It is a collection of essays, verbal sketches, and stories. Irving lived in the palace while writing the book and was instrumental in reintroducing the site to Western audiences.

- Salman Rushdie's The Moor's Last Sigh

- Amin Maalouf's Leon L'Africain, depicting the reconquest of Granada by the Catholic kings.

- Philippa Gregory's The Constant Princess.

Alhambra in music

Alhambra has directly inspired musical compositions as Francisco Tárrega's famous tremolo study for guitar Recuerdos de la Alhambra (Memories of the Alhambra)[1] and Claude Debussy's preludes for piano Lindaraja and La Puerta del Vino.[2].

"En los Jardines del Generalife", first movement of Manuel de Falla's Noches en los Jardines de España, and other pieces by composers as Ruperto Chapí, Tomás Bretón and many others are also ambianced in the Alhambra and its surroundings.

In pop and folk music, Alhambra is the subject of the Ghymes song of the same name.

In September 2006, Canadian singer/composer Loreena McKennitt performed live at the Alhambra. The resulting footage premiered on PBS and was later released as a three-disc DVD/CD set entitled Nights from the Alhambra.

Alhambra is the title of an EP by Canadian rock band The Tea Party, containing acoustic versions of a few of their songs.

Influence in graphic art

M. C. Escher's visit in 1922 inspired his following work on regular divisions of the plane after studying the Moorish use of symmetry in the Alhambra tiles.

Influence in 19th- and 20th-century architecture

From 19th=-century Romantic interpretations right up to the present day, numerous buildings and portions of buildings worldwide have been inspired by the Alhambra: To cite one example, there is a Moorish Revival house in Stillwater, Minnesota, that was created and named after the Alhambra. The main portion of the Irvine Spectrum Center in Irvine, California, is a postmodern version of the Court of the Lions.

One also recalls the renowned Alhambra Theatre in central Bradford, England [3].

Gallery

-

Patio of the palace of Charles V

-

Panoramic view

-

Panoramic view, illuminated at night

-

Mocárabes or honeycomb works

-

Detail looking up wall, Golden Room patio

-

Alhambra illuminated at night

-

The pool of the El Partal Palace

-

Light effects in the Court of Lions

-

Guests in the Comares Palace

-

Alhambra reflections

-

Inside of dome

-

Carved wooden door

-

View east to the Sierra Nevada from the Alcazaba

-

Detail of a wall of the palacios nazaries

-

Columns

-

Carving detail

Media

Template:Multi-video start Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video end

See also

- Alhambra decree: royal decree issued in 1492 ordering the expulsion of all the Jews in Spain.

- Islamic architecture

- Court of the Lions

Piggy Wiggy was here including emma

External links

- Template:Es icon Template:Fr icon Template:En icon www.AlhambraDeGranada.org

- Template:Es icon Template:Fr icon Template:En icon www.alhambra.org

- Template:Es icon Template:Fr icon Template:En icon www.AlhambraGranada.info

- Template:Es icon Template:Fr icon Template:En icon www.alhambra.info

- Template:Es icon Template:Fr icon Template:En icon Template:De icon Template:It icon

- [4] — BBC Four documentary on art in Islamic Spain

Alhambra in turgranada.es Official site for tourism of the province of Granada

- Alhambra Official Guides

- Photos of Alhambra

- Alhambra Architectural Review

- Photos and text

- Alhambra - information on garden history and design

- Detailed study with photos of the Alhambra Granada

- Google maps satellite image

- Article with English translations of the poems on the walls of Alhambra*

- "The Alhambra". Architecture. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- Washington Irving's Tales of the Alhambra

Alhambra

References

- Irwin, Robert. The Alhambra. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Grabar, Oleg. The Alhambra. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1978.

- Jacobs, Michael and Francisco Fernandez. Alhambra. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2000.

- Lowney, Chris. A Vanished World: Medieval Spain’s Golden Age of Enlightenment. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., 2005.

- Menocal, Maria, Rosa. The Ornament of the World. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2002.

- Read, Jan. The Moors in Spain and Portugal. Great Britain: Faber and Faber Limited, 1974.

- Steves, Rick (2004). Spain and Portugal 2004, pp. 204–205. Avalon Travel Publishing. ISBN 1-56691-529-5.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)