Infinity

Infinity (symbolically represented with ∞) comes from the Latin infinitas or "unboundedness." It refers to several distinct concepts (usually linked to the idea of "without end") which arise in philosophy, mathematics, and theology.

In mathematics, "infinity" is often used in contexts where it is treated as if it were a number (i.e., it counts or measures things: "an infinite number of terms") but it is a different type of "number" from the real numbers. Infinity is related to limits, aleph numbers, classes in set theory, Dedekind-infinite sets, large cardinals,[1] Russell's paradox, non-standard arithmetic, hyperreal numbers, projective geometry, extended real numbers and the absolute Infinite.

History

The notion of infinity was invented in India as it first appears in the Vedas.

Early Indian views of infinity

The Isha Upanishad of the Yajurveda (c. 4th to 3rd century BC) states that "if you remove a part from infinity or add a part to infinity, still what remains is infinity".

- Pūrṇam adaḥ pūrṇam idam

- Pūrṇāt pūrṇam udacyate

- Pūrṇasya pūrṇam ādāya

- Pūrṇam evāvasiṣyate.

- That is full, this is full

- From the full, the full is subtracted

- When the full is taken from the full

- The full still will remain — Isha Upanishad.

The Indian mathematical text Surya Prajnapti (c. 400 BC) classifies all numbers into three sets: enumerable, innumerable, and infinite. Each of these was further subdivided into three orders:

- Enumerable: lowest, intermediate and highest

- Innumerable: nearly innumerable, truly innumerable and innumerably innumerable

- Infinite: nearly infinite, truly infinite, infinitely infinite

The Jains were the first to discard the idea that all infinites were the same or equal. They recognized different types of infinities: infinite in length (one dimension), infinite in area (two dimensions), infinite in volume (three dimensions), and infinite perpetually (infinite number of dimensions).

According to Singh (1987), Joseph (2000) and Agrawal (2000), the highest enumerable number N of the Jains corresponds to the modern concept of aleph-null (the cardinal number of the infinite set of integers 1, 2, ...), the smallest cardinal transfinite number. The Jains also defined a whole system of infinite cardinal numbers, of which the highest enumerable number N is the smallest.

In the Jaina work on the theory of sets, two basic types of infinite numbers are distinguished. On both physical and ontological grounds, a distinction was made between asaṃkhyāta ("countless, innumerable") and ananta ("endless, unlimited"), between rigidly bounded and loosely bounded infinities.

Early Greek views of infinity

In accordance with the traditional view of Aristotle, the Hellenistic Greeks generally preferred to distinguish the potentially infinite from the actual infinite; for example, instead of saying that there are an infinity of primes, Euclid prefers instead to say that there are more prime numbers than contained in any given collection of prime numbers (Elements, Book IX, Proposition 20).

However, recent readings of the Archimedes Palimpsest have hinted that at least Archimedes had an intuition about actual infinite quantities.

Logic

In logic an infinite regress argument is "a distinctively philosophical kind of argument purporting to show that a thesis is defective because it generates an infinite series when either (form A) no such series exists or (form B) were it to exist, the thesis would lack the role (e.g., of justification) that it is supposed to play."[2]

Infinity symbol

This article possibly contains original research. (May 2008) |

The precise origin of the infinity symbol ∞ is unclear. One possibility is suggested by the name it is sometimes called—the lemniscate, from the Latin lemniscus, meaning "ribbon." Another theory implies that its origin derives from the respective paganistic symbol, which is supposed to symbolise the total of numbers; its shape is said to represent the repetition.

A popular explanation is that the infinity symbol is derived from the shape of a Möbius strip. Again, one can imagine walking along its surface forever. However, this explanation is not plausible, since the symbol had been in use to represent infinity for over two hundred years before August Ferdinand Möbius and Johann Benedict Listing discovered the Möbius strip in 1858.

It is also possible that it is inspired by older religious/alchemical symbolism. For instance, it has been found in Tibetan rock carvings, and the ouroboros, or infinity snake, is often depicted in this shape.

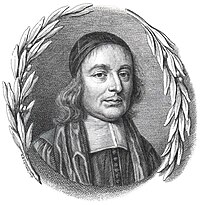

John Wallis is usually credited with introducing ∞ as a symbol for infinity in 1655 in his De sectionibus conicis. One conjecture about why he chose this symbol is that he derived it from a Roman numeral for 1000 that was in turn derived from the Etruscan numeral for 1000, which looked somewhat like CIƆ and was sometimes used to mean "many." Another conjecture is that he derived it from the Greek letter ω (omega), the last letter in the Greek alphabet.[3]

Another possibility is that the symbol was chosen because it was easy to rotate an "8" character by 90° when typesetting was done by hand. The symbol is sometimes called a "lazy eight", evoking the image of an "8" lying on its side.

Another popular belief is that the infinity symbol is a clear depiction of the hourglass turned 90°. Obviously, this action would cause the hourglass to take infinite time to empty thus presenting a tangible example of infinity. The invention of the hourglass predates the existence of the infinity symbol allowing this theory to be plausible.

The infinity symbol is represented in Unicode by the character ∞ (U+221E).

Mathematical infinity

Infinity is used in various branches of mathematics.

Calculus

In real analysis, the symbol , called "infinity", denotes an unbounded limit. means that x grows without bound, and means the value of x is decreasing without bound. If f(t) ≥ 0 for every t, then

- means that f(t) does not bound a finite area from a to b

- means that the area under f(t) is infinite.

- means that the area under f(t) equals 1

Infinity is also used to describe infinite series:

- means that the sum of the infinite series converges to some real value a.

- means that the sum of the infinite series diverges in the specific sense that the partial sums grow without bound.

Algebraic properties

Infinity is often used not only to define a limit but as a value in the affinely extended real number system. Points labeled and can be added to the topological space of the real numbers, producing the two-point compactification of the real numbers. Adding algebraic properties to this gives us the extended real numbers. We can also treat and as the same, leading to the one-point compactification of the real numbers, which is the real projective line. Projective geometry also introduces a line at infinity in plane geometry, and so forth for higher dimensions.

The extended real number line adds two elements called infinity (), greater than all other extended real numbers, and negative infinity (), less than all other extended real numbers, for which some arithmetic operations may be performed.

Complex analysis

As in real analysis, in complex analysis the symbol , called "infinity", denotes an unsigned infinite limit. means that the magnitude of x grows beyond any assigned value. A point labeled can be added to the complex plane as a topological space giving the one-point compactification of the complex plane. When this is done, the resulting space is a one-dimensional complex manifold, or Riemann surface, called the extended complex plane or the Riemann sphere. Arithmetic operations similar to those given below for the extended real numbers can also be defined, though there is no distinction in the signs (therefore one exception is that infinity cannot be added to itself). On the other hand, this kind of infinity enables division by zero, namely for any complex number z. In this context is often useful to consider meromorphic functions as maps into the Riemann sphere taking the value of at the poles. The domain of a complex-valued function may be extended to include the point at infinity as well. One important example of such functions is the group of Möbius transformations.

Nonstandard analysis

The original formulation of the calculus by Newton and Leibniz used infinitesimal quantities. In the twentieth century, it was shown that this treatment could be put on a rigorous footing through various logical systems, including smooth infinitesimal analysis and nonstandard analysis. In the latter, infinitesimals are invertible, and their inverses are infinite numbers. The infinities in this sense are part of a whole field; there is no equivalence between them as with the Cantorian transfinites. For example, if H is an infinite number, then H + H = 2H and H + 1 are different infinite numbers.

Set theory

A different type of "infinity" are the ordinal and cardinal infinities of set theory. Georg Cantor developed a system of transfinite numbers, in which the first transfinite cardinal is aleph-null , the cardinality of the set of natural numbers. This modern mathematical conception of the quantitative infinite developed in the late nineteenth century from work by Cantor, Gottlob Frege, Richard Dedekind and others, using the idea of collections, or sets.

Dedekind's approach was essentially to adopt the idea of one-to-one correspondence as a standard for comparing the size of sets, and to reject the view of Galileo (which derived from Euclid) that the whole cannot be the same size as the part. An infinite set can simply be defined as one having the same size as at least one of its "proper" parts; this notion of infinity is called Dedekind infinite.

Cantor defined two kinds of infinite numbers, the ordinal numbers and the cardinal numbers. Ordinal numbers may be identified with well-ordered sets, or counting carried on to any stopping point, including points after an infinite number have already been counted. Generalizing finite and the ordinary infinite sequences which are maps from the positive integers leads to mappings from ordinal numbers, and transfinite sequences. Cardinal numbers define the size of sets, meaning how many members they contain, and can be standardized by choosing the first ordinal number of a certain size to represent the cardinal number of that size. The smallest ordinal infinity is that of the positive integers, and any set which has the cardinality of the integers is countably infinite. If a set is too large to be put in one to one correspondence with the positive integers, it is called uncountable. Cantor's views prevailed and modern mathematics accepts actual infinity. Certain extended number systems, such as the hyperreal numbers, incorporate the ordinary (finite) numbers and infinite numbers of different sizes.

Our intuition gained from finite sets breaks down when dealing with infinite sets. One example of this is Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel.

Cardinality of the continuum

One of Cantor's most important results was that the cardinality of the continuum () is greater than that of the natural numbers (); that is, there are more real numbers R than natural numbers N. Namely, Cantor showed that (see Cantor's diagonal argument).

The continuum hypothesis states that there is no cardinal number between the cardinality of the reals and the cardinality of the natural numbers, that is, (see Beth one). However, this hypothesis can neither be proved nor disproved within the widely accepted Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, even assuming the Axiom of Choice.

Cardinal arithmetic can be used to show not only that the number of points in a real number line is equal to the number of points in any segment of that line, but that this is equal to the number of points on a plane and, indeed, in any finite-dimensional space. These results are highly counterintuitive, because they imply that there exist proper subsets of an infinite set S that have the same size as S.

The first of these results is apparent by considering, for instance, the tangent function, which provides a one-to-one correspondence between the interval [-0.5π, 0.5π] and R (see also Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel). The second result was proved by Cantor in 1878, but only became intuitively apparent in 1890, when Giuseppe Peano introduced the space-filling curves, curved lines that twist and turn enough to fill the whole of any square, or cube, or hypercube, or finite-dimensional space. These curves can be used to define a one-to-one correspondence between the points in the side of a square and those in the square.

Cantor also showed that sets with cardinality strictly greater than exist (see his generalized diagonal argument and theorem). They include, for instance:

- the set of all subsets of R, i.e., the power set of R, written P(R) or 2R

- the set RR of all functions from R to R

Both have cardinality (see Beth two).

The cardinal equalities and can be demonstrated using cardinal arithmetic:

Mathematics without infinity

Leopold Kronecker rejected the notion of infinity and began a school of thought, in the philosophy of mathematics called finitism which influenced the philosophical and mathematical school of mathematical constructivism.

Physical infinity

In physics, approximations of real numbers are used for continuous measurements and natural numbers are used for discrete measurements (i.e. counting). It is therefore assumed by physicists that no measurable quantity could have an infinite value[citation needed] , for instance by taking an infinite value in an extended real number system (see also: hyperreal number), or by requiring the counting of an infinite number of events. It is for example presumed impossible for any body to have infinite mass or infinite energy. There exists the concept of infinite entities (such as an infinite plane wave) but there are no means to generate such things.

It should be pointed out that this practice of refusing infinite values for measurable quantities does not come from a priori or ideological motivations, but rather from more methodological and pragmatic motivations[citation needed]. One of the needs of any physical and scientific theory is to give usable formulas that correspond to or at least approximate reality. As an example if any object of infinite gravitational mass were to exist, any usage of the formula to calculate the gravitational force would lead to an infinite result, which would be of no benefit since the result would be always the same regardless of the position and the mass of the other object. The formula would be useful neither to compute the force between two objects of finite mass nor to compute their motions. If an infinite mass object were to exist, any object of finite mass would be attracted with infinite force (and hence acceleration) by the infinite mass object, which is not what we can observe in reality.

This point of view does not mean that infinity cannot be used in physics. For convenience's sake, calculations, equations, theories and approximations often use infinite series, unbounded functions, etc., and may involve infinite quantities. Physicists however require that the end result be physically meaningful. In quantum field theory infinities arise which need to be interpreted in such a way as to lead to a physically meaningful result, a process called renormalization.

However, there are some theoretical circumstances where the end result is infinity. One example is the singularity in the description of black holes. Some solutions of the equations of the general theory of relativity allow for finite mass distributions of zero size, and thus infinite density. This is an example of what is called a mathematical singularity, or a point where a physical theory breaks down. This does not necessarily mean that physical infinities exist; it may mean simply that the theory is incapable of describing the sitution properly. Two other examples occur in inverse-square force laws of the gravitational force equation of Newtonian Gravity and Coulomb's Law of electrostatics. At r=0 these equations evaluate to infinities.

Infinity in cosmology

An intriguing question is whether infinity exists in our physical universe: Are there an infinite number of stars? Does the universe have infinite volume? Does space "go on forever"? This is an important open question of cosmology. Note that the question of being infinite is logically separate from the question of having boundaries. The two-dimensional surface of the Earth, for example, is finite, yet has no edge. By travelling in a straight line one will eventually return to the exact spot one started from. The universe, at least in principle, might have a similar topology; if one travelled in a straight line through the universe perhaps one would eventually revisit one's starting point. If, however, the universe is ever expanding, and one's means of transport could not travel faster than this rate of expansion, then conceivably one would never return to one's starting point, even on an infinite time scale, since the starting point would be receding away even as one travels toward it.[citation needed]

A consequence of infinity that is very difficult to visualize is that, when infinite time scales or spaces are considered, if permitted by the laws of physics, the most implausible things that can be imagined, have to happen:

"...when we have an infinite future ... fantastically improbable physical occurrences will eventually have a significant chance of occurring. ... When there is an infinite time to wait, then, anything that can happen, will eventually happen. Worse (or better) than that, it will happen infinitely often."

(John D. Barrow; The book of Nothing. Vacuums, Voids, and the Latest Ideas About the Origins of the Universe. p300)

The existence of life in the Universe could very well be the unavoidable result of infinite/semi infinite space/time scales.

Computer representations of infinity

The IEEE floating-point standard specifies positive and negative infinity values; these can be the result of arithmetic overflow, division by zero, or other exceptional operations.

Some programming languages (for example, J and UNITY) specify greatest and least elements, i.e. values that compare (respectively) greater than or less than all other values. These may also be termed top and bottom, or plus infinity and minus infinity; they are useful as sentinel values in algorithms involving sorting, searching or windowing. In languages that do not have greatest and least elements, but do allow overloading of relational operators, it is possible to create greatest and least elements (with some overhead, and the risk of incompatibility between implementations).

Perspective and points at infinity in the arts

Perspective artwork utilizes the concept of imaginary vanishing points, or points at infinity, located at an infinite distance from the observer. This allows artists to create paintings that 'realistically' depict distance and foreshortening of objects. Artist M. C. Escher is specifically known for employing the concept of infinity in his work in this and other ways.

See also

Notes

- ^ Large cardinals are quantitative infinities defining the number of things in a collection, which are so large that they cannot be proven to exist in the ordinary mathematics of Zermelo-Fraenkel plus Choice (ZFC).

- ^ Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Second Edition, p. 429

- ^ The History of Mathematical Symbols, By Douglas Weaver, Mathematics Coordinator, Taperoo High School with the assistance of Anthony D. Smith, Computing Studies teacher, Taperoo High School.

References

- Amir D. Aczel (2001). The Mystery of the Aleph: Mathematics, the Kabbalah, and the Search for Infinity. Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7434-2299-6.

- D. P. Agrawal (2000). Ancient Jaina Mathematics: an Introduction, Infinity Foundation.

- L. C. Jain (1982). Exact Sciences from Jaina Sources.

- L. C. Jain (1973). "Set theory in the Jaina school of mathematics", Indian Journal of History of Science.

- George G. Joseph (2000). The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics (2nd edition ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-027778-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Eli Maor (1991). To Infinity and Beyond. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02511-8.

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson (1998). 'Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor', MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson (2000). 'Jaina mathematics', MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Ian Pearce (2002). 'Jainism', MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Rudy Rucker (1995). Infinity and the Mind: The Science and Philosophy of the Infinite. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00172-3.

- N. Singh (1988). 'Jaina Theory of Actual Infinity and Transfinite Numbers', Journal of Asiatic Society, Vol. 30.

- David Foster Wallace (2004). Everything and More: A Compact History of Infinity. Norton, W. W. & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-32629-2.

External links

- A Crash Course in the Mathematics of Infinite Sets, by Peter Suber. From the St. John's Review, XLIV, 2 (1998) 1-59. The stand-alone appendix to Infinite Reflections, below. A concise introduction to Cantor's mathematics of infinite sets.

- Infinite Reflections, by Peter Suber. How Cantor's mathematics of the infinite solves a handful of ancient philosophical problems of the infinite. From the St. John's Review, XLIV, 2 (1998) 1-59.

- Infinity, Principia Cybernetica

- Hotel Infinity

- The concepts of finiteness and infinity in philosophy

- Source page on medieval and modern writing on Infinity

- The Mystery Of The Aleph: Mathematics, the Kabbalah, and the Search for Infinity