10 Hygiea

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | A. de Gasparis |

| Discovery date | April 12, 1849 |

| Designations | |

| none | |

| Main belt (Hygiea family) | |

| Adjectives | Hygiean |

| Symbol | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Epoch July 14, 2004 (JD 2453200.5) | |

| Aphelion | 525.311 Gm (3.507 AU)[1] |

| Perihelion | 413.378 Gm (2.770 AU)[1] |

| 469.345 Gm (3.139 AU)[1] | |

| Eccentricity | 0.117[1] |

| 2031.012 d (5.56 a)[1] | |

Average orbital speed | 16.76 km/s |

| 197.965°[1] | |

| Inclination | 3.842°[1] |

| 283.451°[1] | |

| 313.192°[1] | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 500×385×350 km [2] |

| Mass | 8.6 ± 0.7 ×1019 kg [3][4][5] |

Mean density | 2.4 g/cm³ |

| 0.091 m/s² | |

| 0.21 km/s | |

| 27.623 h [1] | |

| Albedo | 0.0717 (geometric)[1] |

| Temperature | ~164 K max: 247 K (−26° C) [6] |

Spectral type | C-type asteroid |

| 9.1[7] to 11.97 | |

| 5.43 | |

| 0.318" to 0.133" | |

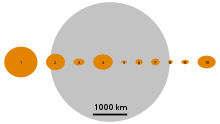

10 Hygiea (Template:PronEng, or as [‘Υγιεία] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)) is the one of the largest known asteroids and is located in the main asteroid belt. With somewhat oblong diameters of 350–500 km, and a mass estimated to be 3% of the total mass of the belt, Hygiea is the fourth largest asteroid in the main belt. It is the largest of the class of dark C-type asteroids with a carbonaceous surface.

Although it is the largest body in its region, due to its dark surface and larger than average distance from the Sun, it appears very dim when observed from Earth. For this reason several smaller asteroids were observed before Annibale de Gasparis discovered Hygiea on April 12, 1849. At most oppositions, Hygiea has a magnitude which is four orders fainter than Vesta, and will require at least a 100 mm telescope to resolve, while at a perihelic opposition, it may be resolvable with 10x50 binoculars.

Discovery and name

Hygiea was discovered by Annibale de Gasparis on April 12, 1849 in Naples, Italy.[8] It was the first of his nine asteroid discoveries. The director of the Naples observatory, Ernesto Capocci, named the asteroid. He chose to call it Igea Borbonica ("Bourbon Hygieia") in honor of the ruling family of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies where Naples was located.[9]

However, in 1852, John Russell Hind wrote that "it is universally termed Hygeia, the unnecessary appendage 'Borbonica' being dropped."[9] The name comes from Hygieia, the Greek goddess of health, daughter of Asclepius (Aesculapius for the Romans).[10] The name was often spelled Hygeia in the nineteenth century, for example in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.[11]

Physical characteristics

Hygiea's surface is composed of primitive carbonaceous material similar to the chondrite meteorites. Aqueous alteration products have been detected on its surface, which could indicate the presence of water ice in the past which was heated sufficiently to melt.[10] The primitive present surface composition would indicate that Hygiea had not been melted during the early period of Solar system formation,[10] in contrast to other large planetesimals like 4 Vesta.

It is the main member of the Hygiea family and contains almost all the mass in this family (well over 90%). It is the largest of the class of dark C-type asteroids with a carbonaceous surface that are dominant in the outer main belt—which lie beyond the Kirkwood gap at 2.82 AU. Hygiea appears to have a noticeably oblate spheroid shape, with an average diameter of 444 ± 35 km and a semimajor axis ratio of 1.11.[10] This is much more than for the other objects in the "big four"—the dwarf planet Ceres and the asteroids 2 Pallas and 4 Vesta. Aside from being the smallest of the four, another important difference from the other four is that Hygiea has a relatively low density, which is comparable to the icy satellites of Jupiter or Saturn more than to the terrestrial planets or the stony asteroids.

While it is the largest body in its region, due to its dark surface and larger than average distance from the Sun it appears very dim when observed from Earth. In fact, it is the third dimmest of the first twenty-three asteroids discovered (only 13 Egeria and 17 Thetis having lower mean opposition magnitudes.[12] At most oppositions, Hygiea has a magnitude of around +10.2,[12] which is as much as four orders fainter than Vesta, and will require at least a 4-inch (100 mm) telescope to resolve.[13] At a perihelic opposition, however, Hygiea can reach +9.1[7] and may just be resolvable with 10x50 binoculars, unlike the next two largest asteroids in the main belt, 704 Interamnia and 511 Davida, which are always beyond binocular visibility.

At least 5 stellar occultations by Hygiea were tracked by Earth-based observers,[14] but all with few observing independent measurements so that much was not learned of its shape. The Hubble Space Telescope was able to resolve the asteroid, and to rule out the presence of any orbiting companions greater than about 16 km in diameter.[15]

Orbit and rotation

Generally Hygiea's properties are the most poorly known out of the "big four" objects in the main belt. Its orbit is much closer to the plane of the ecliptic than those of Ceres, Pallas or Interamnia,[10] but is less circular than Ceres or Vesta with an eccentricity of around 12%.[1] Its perihelion is at a quite similar longitude to those of Vesta and Ceres, though its ascending and descending nodes are opposite to the corresponding ones for those objects. Although its perihelion is extremely close to the mean distance of Ceres and Pallas, a collision between Hygiea and its larger companions is impossible because at that distance they are always on opposite sides of the ecliptic. At aphelion Hygiea reaches out to the extreme edge of the asteroid belt at the perihelia of the Hilda family which is in 3:2 resonance with Jupiter.[16]

It is an unusually slow rotator, taking 27 hours and 37 minutes for a revolution,[1] whereas 6 to 12 hours are more typical for large asteroids. Its direction of rotation is not certain at present, due to a twofold ambiguity in lightcurve data that is exacerbated by its long rotation period—which makes single-night telescope observations span at best only a fraction of a full rotation—but it is believed to be retrograde.[10] Lightcurve analysis indicates that Hygiea's pole points towards either ecliptic coordinates (β, λ) = (30°, 115°) or (30°, 300°) with a 10° uncertainty [2]. This gives an axial tilt of about 60° in both cases.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m 10 Hygiea at the JPL Small-Body Database

- ^ a b M. Kaasalainen; et al. (2002). "Models of Twenty Asteroids from Photometric Data". Icarus. 159: 369. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6907.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ S. R. Chesley; et al. (2005). "The Mass of Asteroid 10 Hygiea". Abstract for American Astronomical Society, DDA meeting #36, #05.05.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ G. Michalak (2001). "Determination of asteroid masses". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 374: 703. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010731.

- ^ Yu. Chernetenko, O. Kochetova, and V. Shor (2005-09-01). "Masses and densities of minor planets". Retrieved 2008-08-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ L.F. Lim; et al. (2005). "Thermal infrared (8–13 µm) spectra of 29 asteroids: the Cornell Mid-Infrared Asteroid Spectroscopy (MIDAS) Survey". Icarus. 173: 385. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.08.005.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b "Bright Minor Planets 2000". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ A. O. Leuschner (1922-07-15). "Comparison of Theory with Observation for the Minor planets 10 Hygiea and 175 Andromache with Respect to Perturbations by Jupiter". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 8 (7). National Academy of Sciences: 170–173. doi:10.1073/pnas.8.7.170. PMID 16586868.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b John Russell Hind (1852). The Solar System: Descriptive Treatise Upon the Sun, Moon, and Planets, Including an Account of All the Recent Discoveries. G. P. Putnam. p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f Barucci, M (2002). "10 Hygiea: ISO Infrared Observations". Icarus. 156: 202. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6775.

- ^ Hartnup, J. (1850). "Observations of Hygeia". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 10: 162.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Moh'd Odeh. "The Brightest Asteroids". The Jordanian Astronomical Society. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "What Can I See Through My Scope?". Ballauer Observatory. 2004. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ^ James L. Hilton. "Asteroid Masses and Densities" (pdf). U.S. Naval Observatory. Lunar and Planetar Institute. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ^ A. Storrs; et al. (1999). "Imaging Observations of Asteroids with Hubble Space Telescope". Icarus. 137: 260. doi:10.1006/icar.1999.6047.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ L’vov V.N., Smekhacheva R.I., Smirnov S.S., Tsekmejster S.D. "Some Peculiarities in the Hildas' Motion" (PDF). Central (Pulkovo) Astronomical Observatory of Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Shape model deduced from lightcurve

- A simulation of the orbit of Hygiea

- Asteroid Database—Detailed View—10 Hygiea

- Yeomans, Donald K. "Horizons system". NASA JPL. Retrieved 2007-03-20. — Horizons can be used to obtain a current ephemeris.