Email spam

- This article discusses spam e-mail. For an overview of the phenomenon of spamming in all electronic media, see Spam (electronic).

Spam by e-mail is a type of spam that involves sending identical (or nearly identical) messages to thousands (or millions) of recipients. Perpetrators of such spam ("spammers") often harvest addresses of prospective recipients from Usenet postings or from web pages, obtain them from databases, or simply guess them by using common names and domains. By definition, spam occurs without the permission of the recipients.

Overview

Sending spam violates the Acceptable Use Policy (AUP) of almost all Internet Service Providers, and can lead to the termination of the sender's account. Many jurisdictions, such as the United States of America, which regulates via the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003, regard spamming as a crime or as an actionable tort.

As the recipient directly bears the cost of delivery, storage, and processing, one could regard spam as the electronic equivalent of "postage-due" junk mail. However, the Direct Marketing Association will point to the existence of "legitimate" e-mail marketing. Most commentators classify e-mail-based marketing campaigns where the recipient has "opted in" to receive the marketer's message as "legitimate".

Spammers frequently engage in deliberate fraud to send out their messages. Spammers often use false names, addresses, phone numbers, and other contact information to set up "disposable" accounts at various Internet service providers. They also often use falsified or stolen credit card numbers to pay for these accounts. This allows them to move quickly from one account to the next as the host ISPs discover and shut down each one.

Spammers frequently go to great lengths to conceal the origin of their messages. They do this by spoofing e-mail addresses (much easier than Internet protocol spoofing). The spammer hacks the email protocol (SMTP) so that a message appears to originate from another email address. Some ISPs and domains require the use of SMTP-AUTH, allowing positive identification of the specific account from which an e-mail originates.

One cannot completely spoof an e-mail address chain, since the receiving mailserver records the actual connection from the last mailserver's IP address; however, spammers can forge the rest of the ostensible history of the mailservers the e-mail has ostensibly traversed. But tracing an email message's route is usually fruitless since many ISPs have thousands of customers and identifying just one spammer is tedious.

Spammers frequently seek out and make use of vulnerable third-party systems such as open mail relays and open proxy servers. The SMTP system, used to send email across the Internet, forwards mail from one server to another; mail servers that ISPs run commonly require some form of authentication that the user is a customer of that ISP. Open relays, however, do not properly check who is using the mail server and pass all mail to the destination address, making it quite a bit harder to track down spammers.

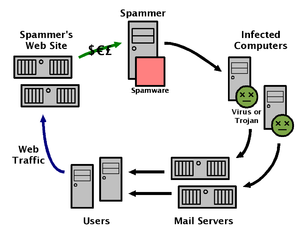

Increasingly, spammers use networks of virus-infected Windows PCs (zombies) to send their spam. Zombie networks are also known as Botnets.

Spoofing can have serious consequences for legitimate email users. Not only can their email inboxes get clogged up with "undeliverable" emails in addition to volumes of spam, they can mistakenly be identified as a spammer. Not only may they receive irate email from spam victims, but (if spam victims report the email address owner to the ISP, for example) their ISP may terminate their service for spamming.

Gathering of addresses

In order to send spam, spammers need to obtain the email addresses of the intended recipients. Toward this end, both spammers themselves and list merchants gather huge lists of potential email addresses. Since spam is, by definition, unsolicited, this address harvesting is done without the consent (and sometimes against the expressed will) of the address owners. As a consequence, spammers' address lists are remarkably inaccurate. A single spam run may target tens of millions of possible addresses -- many of which are invalid, malformed, or undeliverable.

Spam differs from other forms of direct marketing in many ways, one of them being that it costs no more to send to a larger number of recipients than a smaller number. For this reason, there is little pressure upon spammers to limit the number of addresses targeted in a spam run, or to restrict it to persons likely to be interested. One consequence of this fact is that many people receive spam written in languages they cannot read — a good deal of spam sent to English-speaking recipients is in Chinese or Korean, for instance. Likewise, lists of addresses sold for use in spam frequently contain malformed addresses, duplicate addresses, and addresses of role accounts such as postmaster. [1]

Spammers may harvest e-mail addresses from a number of sources. A popular method uses e-mail addresses which their owners have published for other purposes. Usenet posts, especially those in archives such as Google Groups, frequently yield addresses. Simply searching the Web for pages with addresses — such as corporate staff directories — can yield thousands of addresses, most of them deliverable. Spammers have also subscribed to discussion mailing lists for the purpose of gathering the addresses of posters. The DNS and WHOIS systems require the publication of technical contact information for all Internet domains; spammers have illegally trawled these resources for email addresses. Many spammers utilize programs called web spiders to find email addresses on web pages.

Because spammers offload the bulk of their costs onto others, however, they can use even more computationally expensive means to generate addresses. A dictionary attack consists of an exhaustive attempt to gain access to a resource by trying all possible credentials — usually, usernames and passwords. Spammers have applied this principle to guessing email addresses — as by taking common names and generating likely email addresses for them at each of thousands of domain names. [2]

A recent, controversial tactic, called "e-pending", involves the appending of email addresses to direct-marketing databases. Direct marketers normally obtain lists of prospects from sources such as magazine subscriptions and customer lists. By searching the Web and other resources for email addresses corresponding to the names and street addresses in their records, direct marketers can send targeted spam email. However, as with most spammer "targeting", this is imprecise; users have reported, for instance, receiving solicitations to mortgage their house at a specific street address — with the address being clearly a business address including mail stop and office number!

Spammers sometimes use various means to confirm addresses as deliverable. For instance, including a Web bug in a spam message written in HTML may cause the recipient's mail client to transmit the recipient's address, or any other unique key, to the spammer's Web site. [3]

Likewise, spammers sometimes operate Web pages which purport to remove submitted addresses from spam lists. In several cases, these have been found to subscribe the entered addresses to receive more spam. [4]

Delivering spam messages

Internet users and system administrators have deployed a vast array of techniques to block, filter, or otherwise banish spam from users' mailboxes. Almost all Internet service providers forbid the use of their services to send spam or to operate spam-support services. Both commercial firms and volunteers run subscriber services dedicated to blocking or filtering spam, such as Brightmail, Postini, and the various DNSBLs. How, then, do spammers still manage to deliver messages which users wish not to receive and network owners wish not to carry?

Using other people's computers

Early on, spammers discovered that if they sent large quantities of spam directly from their ISP accounts, recipients would complain and ISPs would shut their accounts down. Thus, one of the basic techniques of sending spam has become to send it from someone else's computer and network connection. By doing this, spammers protect themselves in several ways: they hide their tracks, get others' systems to do most of the work of delivering messages, and direct the efforts of investigators towards the other systems rather than the spammers themselves.

In the 1990s, the most common way spammers did this was to use open mail relays. An open relay is an MTA, or mail server, which is configured to pass along messages sent to it from any location, to any recipient. In the original SMTP mail architecture, this was the default behavior: a user could send mail to practically any mail server, which would pass it along towards the intended recipient's mail server.

The standard was written in an era before spamming when there were few hosts on the internet, and those on the internet abided by a certain level of conduct. While this cooperative, open approach was useful in ensuring that mail was delivered, it was vulnerable to abuse by spammers -- and abused it soon was. Spammers could forward batches of spam through open relays, leaving the job of delivering the messages up to the relays. In response, mail system administrators concerned about spam began to demand that other mail operators configure MTAs to cease being open relays. The first DNSBLs, such as MAPS RBL and the now-defunct ORBS, aimed chiefly at allowing mail sites to refuse mail from known open relays.

Within a few years, open relays became rare and spammers resorted to other tactics, most prominently the use of open proxies. A proxy is a network service for making indirect connections to other network services. The client connects to the proxy and instructs it to connect to a server. The server perceives an incoming connection from the proxy, not the original client. Proxies have many purposes, including Web-page caching, protection of privacy, filtering of Web content, and selectively bypassing firewalls. An open proxy is one which will create connections for any client to any server, without authentication. Like open relays, open proxies were once relatively common, as many administrators did not see a need to restrict access to them.

A spammer can direct an open proxy to connect to a mail server, and send spam through it. The mail server logs a connection from the proxy -- not the spammer's own computer. This provides an even greater degree of concealment for the spammer than an open relay, since most relays log the client address in the headers of messages they pass. Open proxies have also been used to conceal the sources of attacks against other services besides mail, such as Web sites or IRC servers.

Besides relays and proxies, spammers have used other insecure services to send spam. One example is the now-infamous FormMail.pl, a CGI script to allow Web-site users to send email feedback from an HTML form. [5] Several versions of this program, and others like it, allowed the user to redirect email to arbitrary addresses. Spam sent through open FormMail scripts is frequently marked by the program's characteristic opening line: "Below is the result of your feedback form."

As spam from proxies and other "spammable" resources grew, DNSBL operators started targeting these as well as open relays. Blocklists such as Blitzed Open Proxy Monitor and Composite Blocking List chiefly target open proxies.

In 2003, spam investigators saw a radical change in the way spammers sent spam. Rather than searching the global network for exploitable services such as open relays and proxies, spammers began creating "services" of their own. By commissioning computer viruses designed to deploy proxies and other spam-sending tools, spammers could harness hundreds of thousands of end-user computers. Most of the major Windows email viruses of 2003, including the Sobig and Mimail virus families, functioned as spammer viruses: viruses designed expressly to make infected computers available as spamming tools. [6] [7]

Besides sending spam, spammer viruses serve spammers in other ways. Beginning in July 2003, spammers started using some of these same viruses to perpetrate distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks upon DNSBLs and other anti-spam resources. [8] Although this was by no means the first time that illegal attacks have been used against anti-spam sites, it was perhaps the first wave of effective attacks. In August of that year, engineering company Osirusoft ceased providing DNSBL mirrors of the SPEWS and other blocklists, after several days of unceasing attack from virus-infected hosts. [9] The very next month, DNSBL operator Monkeys.com succumbed to the attacks as well. [10] Other DNSBL operators, such as Spamhaus, have deployed global mirroring and other anti-DDoS methods to resist these attacks.

As of early 2004, virus-infected hosts remain a major source of spam.

Another way in which the senders of spam use other people's computer resources is in storing the advertising they send until the recipient deletes them. For each spam message sent, millions of copies are stored in millions of recipients' computers. While the cost of storing one message might be negligible, the total cost of storing all the copies by all the recipients is higher. The costs of storing spam by recipients is more than the cost of the physical medium. The space spam occupies cannot be used to store anything else until the spam is erased. Most recipients' mailboxes have limited storage quotas, and when a spam message received causes the recipient's mailbox to reach its prescribed quota, the recipient is denied the right to receive any more email messages. Any email message received contributes to storage quota usage, not only spam messages. The difference is statistical. A single email message sent to one or a few recipients is very unlikely to cause the recipient to stop receiving any more messages. On the other hand, if an average mailbox can hold 10,000 average spam messages, and a spammer sends out 100,000,000 copies of the same message to a 100,000,000 mailboxes, the spammer can be quite sure that as a result about 10,000 of these messages would immediately cause the recipient mailbox to stop receiving further messages.

Legality

Accessing privately owned computer resources without the owner's permission counts as illegal under computer crime statutes in most nations. Deliberate spreading of computer viruses is also illegal in the United States and elsewhere. Thus, some of spammers' most common behaviors are criminal quite independently of the legal status of spamming per se. Even before the advent of laws specifically banning or regulating spamming, spammers have been successfully prosecuted under computer fraud and abuse laws for wrongfully using others' computers.

Cost-based anti-spam methods

The fact that spammers use other people's computers has been an obstacle to some efforts to fight spam. For instance, a number of persons have proposed "email postage" systems, under which email senders would be required to pay money, perform a resource-intensive computation, or post a bond, for each message sent. Evangelists include Microsoft's Bill Gates. The intention of email postage is to deter spam by making it too expensive to send a large number of messages. Since spammers already use other people's computers to spam, there is every reason to believe that they would offload the postage charge onto others as well. This would motivate victims (potential and actual) to secure their computers against such abuse, or trust such 'postage paid' email less.

Using Webmail services

Another common practice of spammers is to create accounts on free webmail services, such as Hotmail, to send spam or to receive emailed responses from potential customers. Because of the amount of mail sent by spammers, they require several email accounts, and use web bots to automate the creation of these accounts. In an effort to cut down on this abuse, many of these services have adopted a system called the captcha: users attempting to create a new account are presented with a graphic of a word, which uses a strange font, on a difficult to read background. Humans are able to read these graphics, and are required to enter the word to complete the application for a new account, while computers are unable to get accurate readings of the words using standard OCR techniques. Blind users of captchas typically get an audio sample.

Spammers have, however, found a means of circumventing this measure. Reportedly, they have set up sites offering free pornography: to get access to the site, a user displays a graphic from one of these webmail sites, and must enter the word. Once the bot has successfully created the account, the user gains access to the porn.

Obfuscating message content

Many spam-filtering techniques work by searching for patterns in the headers or bodies of messages. For instance, a user may decide that all email she receives with the word "Viagra" in the subject line is spam, and instruct her mail program to automatically delete all such messages. To defeat such filters, the spammer may intentionally misspell commonly-filtered words, use Leetspeak or insert other characters, as in the following examples:

- V1agra

- Via'gra

- V I A G R A

- Vaigra

- \/iagra

- Vi@graa

The principle of this method is to leave the word readable to humans (whose pattern-recognition skills make them remarkably adept at picking out the true meaning of misspelled words), but not recognizable to a literally-minded computer program. This is effective up to a point. Eventually, filter patterns become generic enough to recognize the word "Viagra" no matter how misspelled -- or else they target the obfuscation methods themselves, such as insertion of punctuation into unusual places in a word.

(Note: Using most common variations, it is possible to spell "Viagra" in at least 1,300,925,111,156,286,160,896 ways.)

HTML-based email gives the spammer more tools to obfuscate text. Inserting HTML comments between letters can foil some filters, as can including text made invisible by setting the font color to white on a white background, or shrinking the font size to the smallest fine print.

Another common ploy involves presenting the text as an image, which is either sent along or loaded from a remote server. This can be foiled by not permitting a e-mail-program to load images.

As Bayesian filtering has become popular as a spam-filtering technique, spammers have started using methods to weaken it. To a rough approximation, Bayesian filters rely on word probabilities. If a message contains many words which are only used in spam, and few which are never used in spam, it is likely to be spam. To weaken Bayesian filters, some spammers now include lines of irrelevant, random words alongside the sales pitch. A variant on this tactic may be borrowed from the Usenet abuser known as "Hipcrime" -- to include passages from books taken from Project Gutenberg, or nonsense sentences generated with "dissociated press" algorithms. Randomly generated phrases can create spamoetry (spam poetry) or spam art.

Another method used to masquerade spam as legitimate messages is the use of autogenerated sender names in the From: field, ranging from realistic ones such as "Jackie F. Bird" to (either by mistake or intentionally) bizarre attention-grabbing names such as "Sloppiest U. Epiglottis" or "Attentively E. Behavioral". Return addresses are also routinely auto-generated.

Avoiding spam

Computer users can avoid e-mail spam in several ways:

- End-users should take precautions to avoid publicising their e-mail addresses

- End-users can use automated e-mail filtering on their own computers

- System administrators can use appropriate tools to trap e-mail spam at the mail server level

Perhaps the best way to avoid spam involves avoiding making one's email address available to spammers, directly or indirectly. Basic computer literacy should include an understanding of the basics of spamming and spam-avoidance. One should never reply to a spam email, or click an "opt-out" link (this simply confirms that an email address is "live"). Users should not reveal their e-mail addresses on porn, warez and other shady sites.

If a web site requests registration in order to allow useful operations, such as posting in Internet forums, a user may give a temporary disposable address—set up and used only for such a purpose—periodically deleting such temporary email accounts from their e-mail servers. (Users should notify such forums of the new replacement addresses if they wish to continue interaction for valid purposes.)

Anti-spam programmers have released several tools—intended for both end users and for systems administrators—which automate the highlighting, removal or filtering of e-mail spam by scanning through incoming and outgoing e-mails in search of traits typical of spam. A popular commercial solution in this area is a spam firewall appliance from Barracuda Networks.

See also: stopping e-mail abuse

Avoiding sending spam

Anti-spam ISPs and technicians have published a number of resources to help systems and e-mail users avoid sending spam inadvertently or through misunderstanding the e-mail system — such as the MAPS Guidelines for Mailing List Management. These guidelines aim to help legitimate users of bulk e-mail who wish not only to comply with anti-spam laws, but also to avoid appearing to customers or Internet partners as spammers.

Broadly, such guidelines promote the idea that e-mail recipients must grant permission before others may send them bulk e-mail. In effect, senders must not send bulk e-mail to users who have not opted in to receive it. This contrasts with the view of e-mail promoted by many bulk e-mailers, who claim that senders should feel free to send to any user who has not opted out of receiving it.

Many spammers, however, do not even comply with an opt-out régime. Although U.S. and other laws require that commercial e-mailers cease sending to recipients who have opted out, many spam messages contain fraudulent opt-out instructions. In some cases, spammers have used the opt-out function as a way of confirming that someone actually read a spam message. In 2004 some spam messages turned out to contain malware for Microsoft Windows which victims triggered by clicking an opt-out link.

Closed-loop opt-in

One difficulty occurs in implementing opt-in mailing lists: many means of gathering user e-mail addresses remain susceptible to forgery. For instance, if a company puts up a Web form to allow users to subscribe to a mailing list about its products, a malicious person can enter other people's e-mail addresses — to harass them, or to make the company appear to be spamming. (To most anti-spammers, if the company sends e-mail to these forgery victims, it is spamming, albeit inadvertently.)

To prevent this abuse, MAPS and other anti-spam organizations encourage that all mailing lists use closed-loop opt-in (also known as confirmed opt-in or verified opt-in and (by spammers themselves) as double opt-in). That is, whenever an address is presented for subscription to the list, the list software should send a confirmation message to that address. The confirmation message contains no advertising content, so it is not construed to be spam itself — and the address is not added to the list unless the recipient responds to the confirmation message. See also the Spamhaus Mailing Lists vs. Spam Lists page.

All modern mailing list management programs (such as GNU Mailman, Majordomo, and qmail's ezmlm) support closed-loop opt-in by default.

Spam-support services

A number of other online activities and business practices are considered by anti-spam activists to be connected to spamming. These are sometimes termed spam-support services: business services, other than the actual sending of spam itself, which permit the spammer to continue operating. Spam-support services can include processing orders for goods advertised in spam, hosting Web sites or DNS records referenced in spam messages, or a number of specific services as follows:

Some Internet hosting firms advertise bulk-friendly or bulletproof hosting. This means that, unlike most ISPs, they will not terminate a customer for spamming. [11] These hosting firms operate as clients of larger ISPs, and many have eventually been taken offline by these larger ISPs as a result of complaints regarding spam activity. Thus, while a firm may advertise bulletproof hosting, it is ultimately unable to deliver without the connivance of its upstream ISP. However, some spammers have managed to get what is called a pink contract (see below) — a contract with the ISP that allows them to spam without being disconnected.

A few companies produce spamware, or software designed for spammers. Spamware varies widely, but may include the ability to import thousands of addresses, to generate random addresses, to insert fraudulent headers into messages, to use dozens or hundreds of mail servers simultaneously, and to make use of open relays. The sale of spamware is illegal in eight U.S. states. [12] [13] [14]

So-called millions CDs are commonly advertised in spam. These are CD-ROMs purportedly containing lists of email addresses, for use in sending spam to these addresses. Such lists are also sold directly online, frequently with the false claim that the owners of the listed addresses have requested (or "opted in") to be included. Such lists often contain invalid addresses. [15]

A number of DNSBLs, including the MAPS RBL, Spamhaus SBL, and SPEWS, target the providers of spam-support services as well as spammers.

Related vocabulary

The terms unsolicited commercial e-mail (UCE) and unsolicited bulk e-mail (UBE) sometimes appear as more precise or less slang-like expressions for specific types of e-mail spam. Many e-mail users regard all UBE as spam, regardless of its content — but most legislative efforts against spam primarily address UCE. A small but noticeable proportion of unsolicited bulk e-mail is not, in fact, also commercial; examples include political advocacy spam and chain letters.

An ISP which offers special terms of service to spammers has, in the jargon, signed a pink contract — pink referring to the color of SPAM™ luncheon meat. Such a contract might exempt the spammer from the ISP's normal acceptable-use policies, or include an understanding that violations will be overlooked. Similar contracts have specified that the ISP will forward complaints to the spammer, allowing him to remove the complainer from the address list and thus provide the illusion that the spammer has been shut down (this is referred to as list washing); or that a specific level of complaints (or of spam activity) will be tolerated. Certain ISPs have asserted zero tolerance for spam activity — often enough a false claim that it too has become an ironical term.

A site which is friendly to spammers may also be called a black hat, with reference to Western movie cliché in which the villain wears a black cowboy hat. Similarly, an ISP which deals effectively with spammers may be called a white hat. To ask about an ISP's reputation on a public forum (such as news.admin.net-abuse.email) is to do a hat check; the subject line of such a request might be "Foo ISP hat check?" or "What color is Foo ISP's hat?" (The same hat-color metaphor is also used among crackers, albeit with thoroughly different values.)

A Web site promoted by spam advertisements is described as spamvertised, a portmanteau word. Acceptable-use policies generally forbid site operators from advertising a Web site with spam; one sort of pink contract (see above) permits a spammer to host a Web site with the contracting ISP as long as he sends out the spam through a different connection.

The terms opt-out and opt-in refer to the process by which a bulk sender begins sending to a given recipient. In an opt-out scenario, a person starts receiving messages without requesting them, and must request removal from the list. In opt-in, messages go only to those who have requested them. Broadly, opt-out bulk messaging is considered to be spamming, while opt-in bulk messaging is used (e.g.) by legitimate mailing lists. It is, however, possible for an opt-in sender to accidentally send spam, if it does not use confirmed opt-in — that is, verifying that the opt-in request is not forged. Forged subscriptions to otherwise-legitimate mailing lists are a harassment tactic.

Computer viruses such as the Sobig and Mimail strains, which allow spammers to send spam through exploited computers, are termed spammer viruses.

In discussions of spam filtering and automatic email classification, the term Ham e-mail is sometimes used to refer to any email which is not spam.

A more complete list of spam-related vocabulary may be found in the Spam Glossary web page.

Miscellaneous facts about spam email

Larger ISPs such as America Online report that anywhere from one-third to two-thirds of their email server capacity is consumed by spam. Because this cost is imposed without the consent of either the site owners or the authorized users, many argue that email spamming is a form of theft of services.

The term "Spam" derives from a 1970 Monty Python sketch, in which a group of Vikings drown out all conversation in a café by chanting the word over and over.

In May 2004, a reportclaimed that more than 80% of all emails in the United States classed as spam ( [16] ). Steve Linford of the spam-fighting project Spamhaus warned that at current rates of increase, the entire email system could "melt down" within six months. In the same month, email security vendor MessageLabs designated Boca Raton, Florida as "spam capital of the world", saying the small town was the source of a surprisingly high proportion of all spam generated world-wide.

According to an article by James Gleick in The Observer, 2 March 2003 (these figures aren't reliable, they are intended merely to illustrate the impact of spam):

- 10 billion spam emails are sent every day;

- 30 billion are expected by 2005;

- 150 spammers send 90% of all email;

- a new email account set up to experiment received spam within 540 seconds;

- 37% of US email is spam; 8% of UK emails;

- EU businesses spend €10 billion euros each year to deal with spam.

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission estimates that as much as 2/3 of all spam email contains fraudulent offers, forged headers, or other false claims suggestive of criminal activity. [17]

The term "pills, porn and poker" is often used to describe the most common products advertised using E-mail spam.

AOL documented [18] an "unscientific" list of the subjects of the spam most widely sent to its members during 2003. In alphabetical order:

- As seen on Oprah

- Get bigger (also: satisfy your partner, improve your sex life)

- Get out of debt (also: special offer)

- Hot XXX action (also: teens, porn)

- Lowest insurance rates (also: lower your insurance now)

- Lowest mortgage rates (also: lower your mortgage rates, refinance, refi)

- Online degree (also: online diploma)

- Online pharmacy (also: online prescriptions, meds online)

- Viagra online (also: Xanax, Valium, Xenical, phentermine, Soma, Celebrex, Valtrex, Zyban, Fioricet, Adipex, etc.)

- Work from home (also: be your own boss)

Blind users particularly suffer from e-mail spam, because one of the most effective manual techniques for dealing with spam, scanning the list of message subjects to find genuine messages, poses complications for users of screen readers.

Current events

On March 1, 2003 the IAB and IETF created the Anti-Spam Research Group or ASRG within the IRTF to research changes in Internet standards needed to curb spam.

As at 11 July 2003, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission ("FTC") was expected to ask the U.S. Congress for new powers that would let it cooperate closely with other governments and more easily prosecute American and overseas spammers. A 13-page proposal drafted by the FTC to implement legislation entitled the International Consumer Protection Enforcement Act (ICPEA) would render the agency's investigators "spam cops", granting them the power to serve secret requests for subscriber information on Internet service providers, peruse FBI criminal databases and swap sensitive information with foreign law enforcement agencies. The proposed legislation is a result of a push by American legislators to enact strong laws targeting the most extreme spammers. Civil libertarians are alarmed at the ICPEA draft bill, on the basis that it does not contain sufficient checks and balances, and would adversely impact the Freedom of Information Act.

On June 29, 2003, The New York Times reported that Ferris Research estimated that for 2003, the cost of spam is $10 billion in the United States. The estimate factors in the waste in computing resources and work time.

On October 22, 2003, the U.S. Senate voted to outlaw spam e-mails and to set up a "do not spam" registry similar to the recently-put-in-effect "do-not-call" one. Such a registry might actually cause more spam if it gives spammers a list of confirmed "live" addresses, though the final version of the Can Spam Act of 2003, as sent to the President for his signature on December 8th, prohibits the sale or other transfer of an e-mail address obtained through an opt-out request.

On October 24, 2003, a Santa Clara, California Superior Court judge ordered two spammers to pay $2 million for illegally sending unsolicited e-mails.

On December 11, 2003, new UK legislation was passed making it an offence for UK organisations to send unsolicited e-mails. Many experts have expressed doubts over the effectiveness of the new law given that most spam originates outside the UK and the process to convict a spammer would take up to two years to complete.

On December 12, 2003, the state of Virginia arrested two men on felony spamming charges. [19]

On January 22, 2004 a court of law in Denmark fined a company 400.000 DK (€ 54.780) for illegally sending 1.500 unsolicited e-mails.

In January, 2004, Bill Gates proposed at the World Economic Forum at Davos in Switzerland, to charge the sender instead of the recipient of the mail. Such proposals, called "email postage" or "sender pays", have been proposed before and have failed on technical and economic grounds.

In March 2004, with spam email traffic at about 60 percent of all e-mail, America Online Inc. adopted a new anti-spam policy that includes blocking AOL members from access to websites that bulk e-mailers promote.

On April 29, 2004, Federal authorities filed the first criminal charges under the Can Spam Act of 2003 against a group that had spammed ads for allegedly worthless "diet patch" products.

In June 2004 Eric Head, who was sued by Yahoo! under the Can Spam Act, settled the lawsuit for several thousand US dollars.

On November 4, 2004, Jeremy Jaynes, one of the people arrested on December 12, 2003 and rated the 8th most prolific spammer in the world by Spamhaus, was convicted of three felony charges of using servers in Virginia to send thousands of fraudulent emails. The court recommended a sentence of nine years' imprisonment, which was imposed in April 2005 although the start of the sentence is deferred pending appeals. Jaynes was claimed to have an income of $750,000 a month from his spamming activities.

On December 31, 2004, British authorities arrested Christopher Pierson arrested in Lincolnshire, UK and charged him with malicious communication and causing a public nuisance. On January 3, 2005, he pleaded guilty to sending hoax e-mails to relatives of people missing following the Asian tsunami disaster.

On July 25, 2005, Russian spammer Vardan Kushnir was found dead in his Moscow apartment, having suffered numerous blunt-force blows to the head. [20]

See also

- List of e-mail spammers

- Electronic mailing list

- Make money fast

- Netiquette

- Nigerian spam

- Messaging spam

- Complement set email filtering

- Boulder Pledge

- Spamgourmet

Notorious spammers

Newsgroups

Anti-spam advocacy groups

- The International Coalition Against Unsolicited Commercial Email

- The Canadian Coalition Against Unsolicited Commercial Email

- The Coalition Against Unsolicited Commercial Email (USA)

- The European Coalition Against Unsolicited Commercial Email

- Coalition Against Unsolicited Bulk Email, Australia

- Messaging Anti-Abuse Working Group

References

- CNET News.Com: Happy spamiversary, Paul Festa & Evan Hansen

- ZDNet UK: Spammers use free porn to bypass Hotmail protection, Munir Kotadia

External links

- Anti-spam organizations and prominent figures

- Anti Spam Research Group (ASRG) - part of the IRTF, affiliated with the IETF - wikipedia link ASRG

- CAUCE

- The Spamhaus Project

- Spam.abuse.net

- Anti-Spam Technical Alliance (ASTA) Proposal

- California lawyer who sues spammers

- Anti-spam resources

- Address Munging FAQ: Spam-Blocking Your Email Address

- Email Address Harvesting: How Spammers Reap What You Sow by The Federal Trade Commission

- Spam FAQs

- Spam Links

- shortMail.net A disposable email address service that can be used to check email with out giving your real email address out.

- Spamhole A service which generates temporary disposable email addresses for use when potential spammers might harvest an address

- Media articles and press releases

- Yahoo News search for spam-related news (updated regularly)

- Yahoo Domain Keys: Another Ineffective Spam Solution - shumans.com article, 6 December 2003

- The spammers are watching you by Masons, a London-based international law firm

- The War Against Spam - a collection of reading material on the subject

- Good-bye to middle class ISPs - describes the growing separation between spam-friendly and anti-spam ISPs

- Academic papers and reports

- Unsolicited Commercial E-mail Research Six Month Report by Center for Democracy & Technology

- A Plan for Spam

- A white paper from an email client developer http://www.pmail.com/spamwp.htm

- Spam!, Lorrie Faith Cranor and Brian A. LaMacchia, Communications of the ACM, Volume 41, Issue 8 (August 1998), pages 74-83, ISSN:0001-0782

- An Overview of Spam Handling Techniques, Prashanth Srikanthan, Computer Science Department, George Mason University

- Unsolicited Bulk Email: Mechanisms for Control, Paul Hoffman and Dave Crocker, Internet Mail Consortium Report: UBE-SOL, IMCR-008, revised 4 May 1998