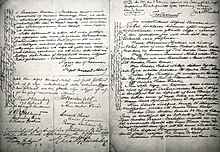

Will and testament

noob = poojdkwelflkfg

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

| Wills, trusts and estates |

|---|

|

| Part of the common law series |

| Wills |

|

Sections Property disposition |

| Trusts |

|

Common types Other types

Governing doctrines |

| Estate administration |

| Related topics |

| Other common law areas |

In common law, a will or testament is a document by which a person (the testator) regulates the rights of others over his or her property or family after death. For the devolution of property not disposed of by will, see inheritance and intestacy. In the strictest sense, a "will" is a general term, while "testament" applies only to dispositions of personal property (this distinction is seldom observed). A will may also create a trust that is effective only after the death of the testator. Any trust created in a will is generally referred to as a "testamentary trust".

Requirements for creation

Any person over the age of majority and of sound mind can draft his or her own will without the aid of an attorney. Additional requirements may vary, depending on the jurisdiction, but generally include the following requirements:

- The testator must clearly identify himself or herself as the maker of the will, and that a will is being made; this is commonly called "publication" of the will, and is typically satisfied by the words "last will and testament" on the face of the document.

- The testator must declare that he or she revokes all previous wills and codicils. Otherwise, a subsequent will revokes earlier wills and codicils only to the extent to which they are inconsistent. However, if a subsequent will is completely inconsistent with an earlier one, the earlier will is considered completely revoked by implication.

- The testator must demonstrate that he or she has the capacity to dispose of his or her property, and does so freely and willingly.

- The testator must sign and date the will, usually in the presence of at least two disinterested witnesses (persons who are not beneficiaries). There may be extra witnesses, these are called "supernumary" witnesses, if there is a question as to an interested-party conflict. In a growing number of states, an interested party is only an improper witness as to the clauses that benefit him or her (this is the case in Illinois, for instance).

- The testator's signature must be placed at the end of the will. If this is not observed, any text following the signature will be ignored, or the entire will may be invalidated if what comes after the signature is so material that ignoring it would defeat the testator's intentions.

After the testator has died, a probate proceeding may be initiated in court to determine the validity of the will or wills that the testator may have created, i.e., which will satisfied the legal requirements, and to appoint an executor. In most cases, during probate, at least one witness is called upon to testify or sign a "proof of witness" affidavit. In some jurisdictions, however, statutes may provide requirements for a "self-proving" will (must be met during the execution of the will), in which case witness testimony may be forgone during probate. If the will is ruled invalid in probate, then inheritance will occur under the laws of intestacy as if a will were never drafted. Often there is a time limit, usually 30 days, within which a will must be admitted to probate. Only an original will can be admitted to probate in the vast majority of jurisdictions– even the most accurate photocopy will not suffice.

There is no legal requirement that a will be drawn up by a lawyer, although there are pitfalls into which home-made wills can fall. The person who makes a will is not available to explain him or herself, or to correct any technical deficiency or error in expression, when it comes into effect on that person's death, and so there is little room for mistake. A common error (for example) in the execution of home-made wills in England is to use a beneficiary (typically a spouse or other close family members) as a witness– although this has the effect in law of disinheriting the witness regardless of the provisions of the will.

Some states recognize a holographic will, made out entirely in the testator's own hand (or, nowadays, typed in a word processor). Contrary to popular opinion, the unique aspect of a holographic will is less that it is written by the testator and more that it need not be witnessed. A minority of states even recognize the validity of nuncupative wills, which are expressed orally. In England, the formalities of wills are relaxed for soldiers who express their wishes on active service.

A will may not include a requirement that an heir commit an illegal, immoral, or other act against public policy as a condition of receipt. In community property jurisdictions, a will cannot be used to disinherit a surviving spouse, who is entitled to at least a portion of the testator's estate. In England, a will may disinherit a spouse, but close relations excluded from a will (including but not limited to spouses) may apply to the court for provision to be made for them at the court's discretion.

It is a good idea that the testator give his executor the power to pay debts, taxes, and administration expenses (probate, etc.). Warren Burger's will did not contain this, which wound up costing his estate thousands. This is not a consideration in English law, which provides that all such expenses will fall on the estate in any case.

Revocation

Methods and effect

Intentional physical destruction of a will by the testator will revoke it, through deliberately burning or tearing the physical document itself, or by striking out the signature. In most jurisdictions, partial revocation is allowed if only part of the text or a particular provision is crossed out. Other jurisdictions will either ignore the attempt or hold that the entire will was actually revoked. A testator may also be able to revoke by the physical act of another (as would be necessary if he is physically incapacitated), if this is done in his presence and in the presence of witnesses. Some jurisdictions may presume that a will has been destroyed if it had been last seen in the possession of the testator but is found mutilated or cannot be found after his or her death.

A will may also be revoked by the execution of a new will. Most wills contain stock language that expressly revokes any wills that came before them, however, because normally a court will still attempt to read the wills together to the extent they are consistent.

In some jurisdictions, the complete revocation of a will automatically revives the next most recent will, while others hold that revocation leaves the testator with no will so that his or her heirs will instead inherit by intestate succession.

In England and Wales, marriage will automatically revoke a will as it is presumed that upon marriage, a testator will want to review the will. A statement in a will that it is made in contemplation of forthcoming marriage to a named person will override this. Divorce, conversely, will not revoke a will, but will have the effect that the former spouse is treated as if they had died before the testator and so will not benefit.

Where a will has been accidentally destroyed, on evidence that this is the case, a copy will or draft will may be admitted to probate.

Dependent relative revocation

Many jurisdictions exercise an equitable doctrine known as dependent relative revocation. Under this doctrine, courts may disregard a revocation that was based on a mistake of law on the part of the testator as to the effect of the revocation. For example, if a testator mistakenly believes that an earlier will can be revived by the revocation of a later will, the court will ignore the later revocation if the later will comes closer to fulfilling the testator's intent than not having a will at all. The doctrine also applies when a testator executes a second, or new will and revokes his old will under the (mistaken) belief that the new will would be valid. However, for some reason the new will is not valid and a court may apply the doctrine to reinstate and probate the old will, as the court holds that the testator would prefer the old will to intestate succession.

Before applying the doctrine, courts may require (with rare exceptions) that there have been an alternative plan of disposition of the property. That is, after revoking the prior will, the testator could have made an alternative plan of disposition. Such a plan would show that the testator intended the revocation to result in the property going elsewhere, rather than just being a revoked disposition. Secondly, courts require either that the testator have recited his mistake in the terms of the revoking instrument, or that the mistake be established by clear and convincing evidence. For example, when the testator made the original revocation, he must have erroneously noted that he was revoking the gift "because the intended recipient has died" or "because I will enact a new will tomorrow."

Election under the will

Also referred to as "electing to take against the will." In the United States, many states have probate statutes which permit the surviving spouse of the decedent to choose to receive a particular share of deceased spouse's estate in lieu of receiving the specified share left to him or her under the deceased spouse's will. As a simple example, under Iowa law (see Code of Iowa Section 633.238 (2005)), the deceased spouse leaves a will which expressly gifts the marital home to someone other than the surviving spouse. The surviving spouse may elect, contrary to the intent of the will, to live in the home for the remainder of his/her lifetime. This is called a "life estate" and terminates immediately upon the surviving spouse's death.

The historical and social policy purposes of such statutes are to assure that the surviving spouse receives a statutorily set minimum amount of property from the decedent. Historically, these statutes were enacted to prevent the deceased spouse from leaving the survivor destitute, thereby shifting the burden of care to the social welfare system.

In history

Charles Vance Millar's will was notorious for offering the bulk of his estate to the Toronto woman who had the greatest number of children in the ten years after his death (the Great Stork Derby). Attempts to invalidate it by his would-be heirs were unsuccessful, and the bulk of Millar's fortune eventually went to four women. Another famous case, Estate of Kidd involved a will found on a deceased Arizona prospector who left his entire $250,000 estate "for research or some scientific proof of a soul of the human body which leaves at death. I think in time there can be a photograph of a soul leaving the human at death."

The Thellusson Will Case was fictionalised by Charles Dickens as Jarndyce and Jarndyce in Bleak House, and led to Parliament legislating against such accumulation of money for later distribution.

Though most people are aware that they need a will, as many as 66% of Americans, according to Consumer Reports, don't have one. Among the notables who died without either a valid will or no will at all are Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant, James A. Garfield, Howard Hughes, Martin Luther King, Jr., Rocky Marciano, Tupac Shakur, Kurt Cobain, Buddy Holly, Lenny Bruce, Billie Holiday, Marvin Gaye, Sam Cooke, Cass Elliot, Sonny Bono, Tiny Tim, Karl Marx and Pablo Picasso.

The shortest known legal will in history is that of Bimla Rishi of Delhi. His will, dated February 9, 1995, translated from Hindi as "all to son". The January 19, 1967 will of Karl Tausch consisted solely of the phrase vše ženě "all to wife".

Freedom of disposition

The conception of the freedom of disposition by will, familiar as it is in modern England and the United States, both generally considered common law systems, is by no means universal. In fact, complete freedom is the exception rather than the rule. Civil law systems often put some restrictions on the possibilities of disposal; see for example "Forced heirship".

Advocates for gays and lesbians have pointed to the inheritance rights of spouses as desirable for same-sex couples as well, through same-sex marriage or civil unions. Opponents of such advocacy rebut this claim by pointing to the ability of same-sex couples to disperse their assets by will. Historically, courts have been more willing to strike down wills leaving property to a same-sex partner for reasons such as incapacity or undue influence.[citation needed] See, for example In Re Kaufmann's Will 20 A.D.2d 464, 247 N.Y.S.2d 664 (1964), aff'd, 15 N.Y.2d 825, 257 N.Y.S.2d 941, 205 N.E.2d 864 (1965)

Terminology

- administrator - person appointed or who petitions to administer an estate in an intestate succession.

- beneficiary - anyone receiving a gift or benefitting from a trust

- bequest - testamentary gift of personal property, traditionally other than money.

- codicil - (1) amendment to a will; (2) a will that modifies or partially revokes an existing or earlier will.

- decedent - the deceased (U.S. term)

- demonstrative legacy - a gift of a specific sum of money with a direction that is to be paid out of a particular fund.

- descent - succession to real property.

- devise - testamentary gift of real property.

- devisee - beneficiary of real property under a will.

- distribution - succession to personal property.

- executor/executrix or personal representative [PR] - person named to administer the estate, generally subject to the supervision of the probate court, in accordance with the testator's wishes in the will. In most cases, the testator will nominate an executor/PR in the will unless that person is unable or unwilling to serve.

- inheritor - a beneficiary in a succession, testate or intestate.

- intestate - person who has not created a will prior to death.

- legacy - testamentary gift of personal property, traditionally of money. Note: historically, a legacy has referred to either a gift of real property or personal property.

- legatee - beneficiary of personal property under a will, i.e., a person receiving a legacy.

- probate - legal process of settling the estate of a deceased person.

- specific legacy (or specific bequest) - a testamentary gift of a precisely identifiable object.

- testate - person who dies having created a will before death.

- testator - person who executes or signs a will; that is, the person whose will it is. The antiquated English term of testatrix was used to refer to a female but is generally no longer in standard legal usage.

See also

References

External links

- Court TV's Famous Wills

- Prerogative Court of Canterbury wills (1384 - 1858) available for download

- William Shakespeare's Will

- Jane Austen's Will

- Getting copies of UK wills made after 1858

- List of UK Regional Probate Registries - Regional Offices for probate information and to register the location of a Will and/or Executor

- UK Will writing service with charity donation

- Guide To Online Wills