Chinese characters

Chinese characters or Han characters (simplified Chinese: 汉字; traditional Chinese: 漢字; pinyin: Hànzì) are logograms used in the written forms of the Chinese language, and to varying degrees in the Japanese and Korean languages (though the latter only in South Korea). Use of Chinese characters has disappeared from the Vietnamese language — in which they were used until the 20th century — and from North Korea, where in normal writing they have been completely replaced by Hangul.

Contrary to popular belief, only a small number of Chinese characters are pictograms. Most characters are based on other characters that were homonyms when the character was created.

Chinese characters are called hànzì in Mandarin Chinese, kanji in Japanese, hanja or hanmun in Korean, and hán tự (also used in the chu nom script) in Vietnamese. However, the last is considered an extremely sinified form and Chinese characters are normally called chữ nho (字儒). (Note that the morphemes are reversed as is common in Vietnamese borrowings from Chinese.) In modern written Chinese, characters are written either in Traditional Chinese characters (used in Taiwan and Hong Kong) or Simplified Chinese characters (used in Mainland China, Malaysia and Singapore)

In Chinese, a word or phrase (词/詞 cí) (a unit of meaning) is composed of one or more characters (字 zì), for instance the phrase 汉字/漢字 hànzì is composed by two characters. Each Chinese character represents a single syllabic unit in all spoken variants of Chinese still existing today. However, unlike modern Chinese dialects, Archaic Chinese had consonant clusters and lacked a tonal feature, for example 角 jiǎo is pronounced klak in Archaic Chinese.

Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese are not linguistically related to Chinese, and in order to make Chinese characters work in those languages with radically different grammar, many adaptations had to be made. In Japanese, kanji are used to represent not only borrowings from Chinese, which are monosyllabic, but also native words (Kun'yomi), which are often multisyllabic.

In many cases in these languages, there are differences from characters used in Chinese. Japanese has standardised on a set of 1,945 characters, known as the Jōyō kanji, which includes simplified or variant forms of characters traditionally used in China, as well as a number of Chinese characters created by the Japanese themselves.

In China itself, thousands of simplified characters were created or adopted in mainland China in the twentieth century, creating a distinction between, for example, 汉 in simplified characters used in mainland China and Singapore, and 漢 in traditional characters used in Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Just as Roman letters have a characteristic shape (lower-case letters occupying a roundish area, with ascenders or descenders on some letters), Chinese characters tend to occupy a more-or-less square area. Characters made up of multiple parts squash these parts together in order to maintain a uniform size and shape. Because of this, beginners often practise on squared or graph paper, and the Chinese sometimes call Han characters 方块字 fāngkuài zì "square characters".

Origin

The oldest Chinese inscriptions that are clearly writing are the poorly understood Oracle Script (甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén) of the late Shang Dynasty (or Yin (殷) Dynasty), attested from about 1200 BC. Only about 1400 of the 2500 known Oracle Script glyphs can be identified with later Chinese characters and can therefore be easily read.

There have been suggestions that this was not designed for the Chinese language, or even for a Sino-Tibetan language, because it does not seem to reflect Chinese morphology accurately. An analogy would be if English were written with a script that had a single character for die and kill, but two separate characters for warm in "it's a warm day" and "please warm the bath". Although the succeeding Zhou Dynasty was clearly Han Chinese, it's not clear which ethnic group the Shang were. One possibility is Miao (苗 Miáo). The first recorded Miao kingdom was Jiuli. The ancestors of the Jiuli are thought to be the Liangzhu people, and it is these who are credited with creating the Oracle Script. According to Chinese legend, Jiuli was defeated by the military unification of Huang Di (黃帝 Huángdì) and Yandi, leaders of the Huaxia (華夏 Huáxià) tribe (the ancestors of the Han Chinese) as they struggled for supremacy of the Huang He valley. After their defeat, the Jiuli people who were not absorbed into the new Zhou state moved south, splitting into the Miao and the Li (黎 lí) peoples.

The Yi script is quite old and is superficially similar to Chinese, but does not seem to be derived from it. It's perhaps likely that it was inspired by the example of Chinese, but the possibility cannot be discounted that it and the Chinese script both descend from a common source such as the Oracle Script.

Styles

The earliest Chinese characters are the so called Oracle Script of the late Shang Dynasty, followed by the Bronzeware Script or (金文) jīnwén during the Zhou Dynasty. These scripts no longer serve as anything but a source for scholars.

The first script that is still in (restricted) use today is the "Seal Script" or 篆書[篆书] zhuànshū. It is the result of the efforts of the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, in the standardization of the Chinese script. The Seal Script, as the name suggests, is now only used in artistic seals. Few people are still able to read the seal script, although the art of carving a traditional seal in the seal script remains alive in China today.

Scripts that are still used regularly for print are the "Clerk Script" or 隸書[隶书] lìshū, the "Wei Monumental" or 魏碑 wèibēi, the "Regular Script" or 楷書[楷书] kǎishū, the "Song Style" or 宋體[宋体] sòngtǐ (mainly used in printing and computer fonts), and the "Running Script" or 行書[行书] xíngshū. Modern Chinese handwriting is usually modeled on the Running Script.

Finally, there is the "Draft Script" (also called "Grass Script"), or 草書[草书] cǎoshū. The draft script is an idealized calligraphic style, where characters are suggested rather than realized. Despite being cursive to the point where individual strokes are no longer differentiable, the draft script is highly revered for the beauty and freedom that it embodies. Many simplified Chinese characters are based on this style.

Radicals

Main article: radical

Each character has a fundamental component, or radical (部首 Chinese: bù shǒu, Japanese: bushu, literally "initial portion"), and this design principle is used in Chinese dictionaries to logically order characters in sets.

Full characters are ordered according to their initial radical, which fall into roughly 200 types. Then these are subcategorised by their total number of strokes.

Classification

See also: Chinese character classification

Chinese scholars have traditionally classified Han characters into six types by etymology (六书).

The first two types are single-body (独体), which means that the character was created independent of other Chinese characters preceding it.

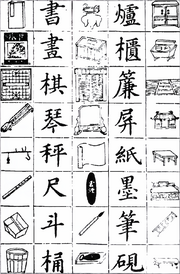

The first type, and the type most often associated with Chinese writing, are pictograms(象形字), which are pictorial representations of the morpheme represented.

The second type are ideograms(指事字) that attempt to graphicalize abstract concepts, such as "up" (上) and "down" (下). Also considered ideograms are pictograms with an ideographic indicator; for instance, 刀 is a pictogram meaning "knife", while 刃 is an ideogram meaning "blade".

Although the perception of most Westerners is that these are how most characters are created, pictograms and ideograms actually take up but a small proportion of Chinese logograms.

The next two types are called combined-body (合体), or compounds which means that the character was created from assembling other characters together. Note that despite being called "compounds", these logograms are single entities in themselves; they are written so that they take up the same amount of space as any other logogram.

The third type of characters are radical-radical compounds(會意字), in which each element (radical) of the character hints at the meaning.

The fourth type is of radical-phonetic compounds(形聲字), in which one component (the radical) indicates the kind of concept the character describes, and the other hints at the pronunciation. This last type accounts for the majority of Chinese logograms.

The final two types are rarer.

Changed-annotation characters (转注字) are characters which were originally the same character but have bifurcated through orthographic (and often linguistic) drift. For instance, 考 and 老 were once the same character, meaning "elder person", but 考 now means "test" and 老 means "old".

Fake-borrowed characters (假借字) are created when a native spoken word has no corresponding character, and therefore another character with the same or similar sound (and often a vaguely similar meaning) is "borrowed" to represent the new word. Occasionally the new meaning can supplant the old meaning. For instance, the character 自 used to be a pictographic word meaning "nose", but was borrowed to mean "self" -- and is now known almost exclusively as "self". However, the "nose" meaning survives in compounds. Note that Japanese Kana can all be considered to be of this type, hence the name "kana" (仮名, where 仮 is a simplified form of 假).

Note that due to the long period of language evolution, such component "hints" within characters are often useless and sometimes quite misleading in modern usage. This is particularly true in non-Chinese languages.

Classification has its own problems, as the origins of characters are often obscure. For example, the character for "East" (東; Chinese: dōng, Japanese: higashi and tō), which combines the "tree" radical (木) and the "sun" radical (日), is usually considered a radical-radical compound. Though it appears to represent a sun rising through trees, and this is both an evocative image and a useful mnemonic, the origin and classification of the character are disputed among scholars. While some agree with the radical-radical classification, others see it as a unique character in and of itself — some claim it as being derived from an early pictograph of bundled sticks.

As another example, the character for "mother" (媽 in Chinese mā) consists of one component meaning "female" (女) and another one meaning "horse" (馬 mǎ). The first component denotes a female entity, whereas the second suggests the pronunciation by referring to the word for "horse". The reason that "horse" was chosen to represent mother may be that horses — in a historical context — were often used to represent "steadfastness". The majority of Chinese characters, like this example, have one component that suggests the meaning and another that suggests pronunciation. In many cases, even the component intended to suggest pronunciation has an abstract semantic relation to the idea expressed by the character. This is possible because the phonetic system of Chinese allows for many words to have the same pronunciation (homonymy), and because the consideration of phonetic similarity used in a character generally ignores its tone and the manner of articulation of its initial consonant (but not the place of articulation).

Orthography

Usually Chinese characters each take up the same amount of space. One of the easiest ways for beginners to ensure this is with a grid as guidance. In addition to strictness in the amount of space a character takes up, Chinese characters are written with very precise rules. The three most important rules are the strokes employed, the stroke placement, and the order with which they are written (see Stroke order). Most words can be written with just one stroke order, though some words also have variant stroke orders, which may result in different stroke counts. On a larger scale, Chinese text is traditionally written from top to bottom and then right to left, but it is more common today to see the same orientation as Western languages: going from left to right and then top to bottom. Most punctuation marks were adopted from the West, but there are a few exceptions: for example, names of books are marked with a wavy line drawn to their right in vertical text, or enclosed in a special double pointed bracket in horizontal text.

Common errors while writing Chinese characters include incorrect stroke direction, incorrect stroke order, incorrect stroke length relative to other strokes, and incorrect placement of strokes relative to other strokes. Each mistake is highly visible to the literate eye due to the imperfections of the human fingers, as well as the weight given to the different parts of a stroke. Mistakes are often shunned, as they are marks of illiteracy or incompetence. In a culture that values scholarship as its highest virtue, such attributions are highly undesirable. Because of this strictness in not only the image of the character, but how the image is produced, it is considered by many the most difficult to learn properly.

Due to the long history of China, as well as many stylistic variations that have developed and the many attempts by past rulers to standardize writing, some characters have multiple forms. The characters themselves can be considered separate, but often are merely derivatives of each other in that their composition is of the same root. They are often not considered simplifications, as their stroke count is sometimes the same, and often lessened only but a slight amount. The most famous today is probably the character for sword (劍), where the radical (on the right) is knife (刀). The same word can be written with different forms for the radical, including using 刃 or 刀 itself.

The usage of traditional characters versus simplified characters varies greatly, and can depend on both the local customs and the medium. Often, simplified characters would be used in everyday writing, or quick scribblings, while traditional characters would be used in printed works. However, the PRC's adoption of simplified characters has almost completely removed all traces of their traditional counterparts, save for in Hong Kong and Macau. There is no absolute rule for using either system, and often, it is determined by what the target audience understands, as well as the upbringing of the writer. In addition there is a special system of characters used for writing numerals in financial contexts; these characters are deliberately chosen to be complicated, to prevent forgeries or alterations.

Dictionaries

The design and use of a dictionary of Chinese characters presents interesting problems. Dozens of indexing schemes have been created for the Chinese characters. The great majority of these schemes — beloved by their inventors but nobody else — have appeared in only a single dictionary; only one such system has achieved truly widespread use. This is the system of radicals.

Chinese character dictionaries often allow users to locate entries in several different ways. Many Chinese, Japanese, and Korean dictionaries of Chinese characters list characters in radical order: characters are grouped together by radical, and radicals containing fewer strokes come before radicals containing more strokes. Under each radical, characters are listed by their total number of strokes. In Japanese and Korean dictionaries, it is usually possible to search for characters by sound, using Kana and Hangul. Most dictionaries also allow searches by total number of strokes, and individual dictionaries often allow other search methods as well.

For instance, to look up the character 松 (pine tree) in a typical dictionary, the user first determines which part of the character is the radical, then counts the number of strokes in the radical (in this case four), and turns to the radical index (usually located on the inside front or back cover of the dictionary). Under the number 4, the user locates the radical 木, then turns to the page number listed, which is the start of the listing of all the characters containing this radical. This page will have a sub-index giving stroke numbers and page numbers. The right half of the character also contains four strokes, so the user locates the number 4, and turns to the page number given. From there, the user must scan the entries to locate the character he or she is seeking. Some dictionaries have a sub-index which lists every character containing each radical, so that if the user knows the number of strokes in the non-radical portion of the character, he or she can locate the correct page number directly.

In Korean, character dictionaries are usually called Okpyeon (옥편; 玉篇), which literally means "Jewel Book", rather like the Latin word thesaurus ("treasure"). 玉篇 is also the name of a fourth-century Chinese dictionary from the Liang Dynasty.

Another popular dictionary system is the four corner method.

Most Chinese-English dictionaries and Chinese dictionaries sold to English speakers use the radical lookup method combined with an alphabetical listing of characters based on their pinyin romanization system. To use one of these dictionaries, the reader finds the radical and stroke number of the character, as before, and locates the character in the radical index. The character's entry will have the character's pronunciation in pinyin written down; the reader then turns to the main dictionary section and looks up the pinyin spelling alphabetically, just as if it were an English dictionary.

Derivatives of Han characters

Besides Korean and Japanese, a number of Asian languages have historically been written with Han characters, or with characters modified from Han characters. They include:

- Vietnamese language (Chữ nôm)

- Khitan language (ja:契丹文字)

- Tangut language (fr:Tangoute, zh:西夏文, [1], [2])

- Zhuang language

- Miao language [3]

- Nakhi language (Geba script)

In addition, the Yi script is similar to Han, but is not known to be directly related to it.

Jurchen language (ja:女真文字) used a ideographic script consisted of original characters with a few Han borrowings.

Number of Chinese characters

The question of how many characters there are is still the subject of debate. In the 18th century, European scholars claimed the total tally to be about 80,000. This number, however, is thought to be exaggerated as the character count varies by dictionary and its comprehensiveness. For example, the Kangxi Dictionary lists about 40,000 characters, while the modern Zhonghua Zihai lists in excess of 80,000. One reason for the overwhelming number of characters is due to the existence of rarely-occurring variant and obscure characters (many of which are unused, even in Classical Chinese). Note, however, that no two characters are ever contextually identical.

The large number of Chinese characters is due to their logographic nature — for every morpheme there must be a symbol, and sometimes there are variant characters have developed for the same morpheme. It has also been claimed that the sheer number of characters is used as a way to separate scholars from the ordinary, and perhaps even to keep certain texts from being read by but the most scholarly.

Chinese

It is usually said that about 3,000 characters are needed for basic literacy in Chinese (for example, to read a Chinese newspaper), and a well-educated person will know well in excess of 4,000 to 5,000 characters. Note that it is not necessary to know a character for every known word of Chinese, as the majority of modern Chinese words are compounds made of two or more morphemes, and are thus written not with a single unique character, but with multiple, usually common, characters. There are 6763 code points in GB2312, an early version of the national standard used in the People's Republic of China. GB18030 has a much higher number. The Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi proficiency test covers approximately 5000 hanzi.

There are 4808 characters in Taiwanese Ministry of Education's list of regularly used Chinese characters. (常用國字標準字體表) The Chinese Standard Interchange Code (CNS11643) - the official national standard - supports 48027 characters, while the most widely-used encoding scheme, BIG-5, supports only 13053.

In addition, there are a large number of dialect characters which are not used in formal Chinese written language, but are used to represent colloquial terms in non-Mandarin Chinese spoken forms.

Japanese

In Japanese there are 1945 "daily use kanji" (常用漢字 jōyō kanji) designated by the Japanese Ministry of Education. These are taught during primary and secondary school. Publications which include characters which fall outside this list should print furigana or rubi alongside the characters as a phonetic guide, however such guidance is often omitted for those characters that many are familiar with.

Upon formalization of the daily-use kanji, government offices and newspapers were encouraged to abandon all other characters. This created an immediate problem with placenames and personal names, which did not conform to the list and yet had been used in localities and families for hundreds of years. As a result, map production and birth registration processes were impeded. To resolve this issue, the government drew up a list of approximately one thousand additional characters, referred to as "name kanji" (jinmeiyō kanji #20154;名用漢字) used in personal and geographical names. For further information, see the Names section of the main Kanji article. This brought the total number of government-supported characters to 2928.

There is some speculation that many of the "odd" kanji on the names list were promoted in an attempt to make a de-facto expansion of the Jouyou Kanji List, rather than with the serious idea that anyone will use them in names. The idea of reducing the number of kanji in use has been a politically contentious issue, with many conservatives believing that kanji are culturally Japanese and that people should use them frequently.

Today, a well-educated Japanese person may know upwards of 3500 kanji. The Kanji kentei (日本漢字能力検定試験 Nihon kanji nōryoku kentei shiken or Test of Japanese Kanji Aptitude) tests the ability to read and write kanji. The highest level of the Kanji kentei tests the ability to read and write 6000 kanji, though in practice few people attain this level as Japanese language generally uses fewer Chinese characters than Chinese does, and literacy in Japanese requires knowledge of fewer Chinese characters than literacy in Chinese.

Korean

In South Korea, middle and high school students learn 1,800 to 2,000 basic characters (Hanja), but most people use Hangul exclusively in their day-to-day lives. Hanja are still used to some extent, particularly in newspapers, weddings, place names and calligraphy. Hanja is also extensibly used in situations where ambiguity must be avoided, such as high-level corporate reports and government documents.

In North Korea, Hanja is rarely used.

Vietnamese

Although now nearly extinct in Vietnamese, varying scripts of Chinese characters were used to write the language, with use of Chinese characters becoming limited to ceremonial uses beginning in the 19th century. Similarly to Japan and Korea, Chinese was used by the ruling classes, and the characters were eventually adopted to write Vietnamese. To express native Vietnamese words which had different pronunciations than the Chinese, Vietnamese developed the Chu Nom script which added diacritical marks to distinguish native (Vietnamese) words from Chinese.

Rare and complex characters

Often a character which is not commonly used (called "rare" or "variant" characters) will appear in a personal or place name in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean names (see Chinese name, Japanese name, and Korean name respectively). This has caused problems as many computer encoding systems include only the 5,000 or so most common characters and exclude the less often used characters. This is especially a problem for personal names which often contain rare or classical characters.

People who have run into this problem include Taiwanese politicians Wang Chien-shien (王建煊) and Yu Shyi-kun (游錫堃) and Taiwanese singer David Tao (陶喆). Newspapers have dealt with this problem in varying ways, including trying to create a character from two characters, including a picture, or, especially as is the case with Yu Shyi-kun, simply omitting the rare character with the hope that the reader will be able to infer who it refers to. Japanese newspapers may render such names and words in katakana instead of kanji, and it is common practice for people to write names for which they are unsure of the correct kanji in katakana instead.

There are also some extremely complex characters which have understandably become rather rare. According to Bellassen (1989), the most complex Chinese character is 𪚥 zhé (if the character is not rendered on your browser, refer to the image to the right instead), meaning "verbose" and boasting sixty-four strokes; although it fell from use around the fifth century AD. It might be argued, however, that while boasting the most strokes, it is not necessarily the most complex (in terms of difficulty) character, as it simply requires writing the same sixteen-stroke character four times (albeit in the space alloted for one).

An 84-stroke kokuji (Japanese-created kanji) also exists [4] - composed of 3 clouds (雲) on top of 龘 (3 dragons; the appearance of a dragon walking), it has the kun-yomi odoto, taito and daito.

The most complex character found in contemporary Chinese dictionaries is 齉 nàng , meaning "unclear pronouncing due to snuffle", with "just" thirty-six strokes.

The most complex character still in use may be 'biáng', with 57 strokes (refer to the image to the right), which refers to Biang Biang Noodles, a type of noodle from China's Shaanxi province. This character cannot be found in modern Chinese dictionaries.

In contrast, the simplest character is 一 yī, "one", with just one stroke. The most common character is 的 de, a grammatical particle usually translatable as "of", with eight strokes. According to Bellassen (1989), the average number of strokes in a character is 9.8 (though it is unclear whether this average is weighted or includes traditional characters).

See also

- Chinese calligraphy

- Chinese character encoding

- Chinese characters for chemical elements

- Chinese characters of Empress Wu

- Chinese input methods for computers

- Earthly Branches

- Eight Principles of Yong

- Heavenly Stems

- Simplified Chinese character

- Stroke order

- Traditional Chinese character

- Shodo Japanese calligraphy

- Xiandai Hanyu changyong zibiao (现代汉语常用字表, modern Chinese characters list; like Jōyō kanji in Japan)

- Blissymbols

References

- Bellassen, Joël & Zhang Pengpeng (1989). Méthode d'Initiation à la Langue et à l'Écriture chinoises. La Compagnie. ISBN 2-9504135-1-X.

External links

- A Typographic Outcry: a curious perspective

- Chinese characters and culture

- Articles about Chinese Characters

- Chinese Character Dictionary: Look up simplified and traditional characters by English definition, pinyin, Cantonese, and radical/stroke.

- Generator for Chinese typographical filler text

- If English was written like Chinese

- Chinese Symbols Introduction to Chinese Symbols

- Chinese: a selection about Chinese characters from Visible Speech: The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems, by John DeFrancis