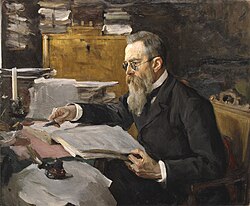

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (Russian: Николай Андреевич Римский-Корсаков, Nikolaj Andreevič Rimskij-Korsakov), also Nikolay, Nicolai, and Rimsky-Korsakoff, (18 March [O.S. 6 March] 1844 – 21 June [O.S. 8 June] 1908) was a Russian composer, and a member of the group of composers known as "The Five." Noted particularly for a predilection for folk and fairy-tale subjects as well as his extraordinary skill in orchestration, his best known orchestral compositions—Capriccio espagnol, Russian Easter Festival Overture, and the symphonic suite Scheherazade—are considered staples of the classical music repertoire, along with suites and excerpts from some of his 15 operas.

Rimsky-Korsakov hewed initially to the beliefs of fellow composer Mily Balakirev and critic Vladimir Stasov in developing a nationalistic style of composition that utilized Russian folk song and lore while eschewing traditionally Western compositional methods. While Rimsky-Korsakov embraced folk song and subjects for the musical and programmatic content of his compositions throughout his career, he came to appreciate Western musical techniques after becoming a professor of harmony and orchestration at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1871. Putting himself through a rigorous three-year program of self-education in his initial years at the institute, he became a master of Western methods, which he incorporated into his own works alongside the influences of Mikhail Glinka and his fellow members of The Five. His techniques of composition and orchestration would become further enriched by his exposure to the works of Richard Wagner.[1]

Despite current controversy over his editing of the works of Modest Mussorgsky,[2] Rimsky-Korsakov is now suggested in the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians as "the main architect" of what is now recognized by the public as the Russian style of composition.[3] This is due not only to the considerable legacy of his own compositions, but also from his editing and preparing works by The Five for performance, which brought them into the active classical repertoire, as well as his shaping of younger composers and musicians during his decades as an educator. Gerald Abraham concludes in Grove that Rimsky-Korsakov's "own style, pellucid and based on the bold use of primary instrumental colors over a framework of clearly defined part-writing and harmony, was based on Glinka and Balakirev, Berlioz and Liszt. He transmitted it directly to two generations of Russian composers from Lyadov (b 1855) and Glazunov (b 1865) to Myaskovsky (b 1881), Stravinsky (b 1882) and Prokofiev (b 1891), all of whom were his pupils, and his general influence is evident, if less pronounced, in the orchestral music of Ravel, Debussy, Dukas and Respighi."[1]

Life

Early years

Rimsky-Korsakov was born at Tikhvin, 200 km. east of St. Petersburg, into an aristocratic family with a long line of military and naval service. He showed musical ability early, and beginning at six, Rimsky-Korsakov had piano lessons from various local teachers and showed a tendency to compose.[4] However, at his family's insistence he entered the Imperial Russian Navy in 1856, studying at the School for Mathematical and Navigational Sciences in St. Petersburg and taking his passing-out examination in April 1862.[4]

While at school, Rimsky-Korsakov took piano lessons from a man named Ulikh.[5] Ulikh saw, however, that Rimsky-Korsakov had serious musical talent and recommended another teacher, Feodor A. Kanille (Théodore Canillé), with whom he took lessons in piano and composition beginning in the autumn of 1859.[6] Kanille exposed him to much new music, including that of Mikhail Glinka and Robert Schumann.[6] When Rimsky-Korsakov was 17, these lessons were cancelled.[6] Regardless, Kanille told Rimsky-Korsakov to continue coming every Sunday,[7] not for formal lessons but to play duets and discuss music.[8] Then, in November 1861, Kanille introduced him to Mily Balakirev, who in turn introduced him to César Cui, and Modest Mussorgsky; all three were in their 20s but already known as composers.[9]

Balakirev encouraged Rimsky-Korsakov to compose, teaching him when he was not at sea.[6] He also prompted Rimsky-Korsakov to enrich himself in other areas.[10] He showed Balakirev the beginning of a symphony in E-flat minor that he had written; Balakirev insisted that he continue his efforts on it. By the time Rimsky-Korsakov sailed on a three-year world cruise in late 1862, he had completed three movements of the symphony.[11][12] He wrote the slow movement during a stop in England, then mailed the score to Balakirev before going back to sea.[13] Balakirev conducted the successful premiere of the symphony in December 1865 at one of the Free School of Music concerts in St. Petersburg.[14] A second performance followed in March 1866 under the direction of Konstantin Lyadov (father of composer Anatoly Lyadov).[15]

Active composer

Rimsky-Korsakov's naval duties now occupied only two or three hours a day, leaving considerable time for composition and a social life.[15] He began but abandoned a symphony in B minor, feeling it too closely modeled on Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. He completed an Overture on Three Russian Themes, based on Balakirev's folksong overtures, which was performed at a Free School concert in December 1866, and composed the initial version of his orchestral pieces Sadko (1867) and Antar (1868).[15] He became friends with Alexander Borodin, whose music "astonished" him,[16] spending time with him, Balakirev and, increasingly, Modest Mussorgsky, critiquing one another's works in progress and sometimes also collaborating on new pieces.[6] Rimsky-Korsakov became especially noted for his talents as an orchestrator.[15] He was asked by Balakirev to orchestrate a Schubert march for a concert in May 1868, by Cui to orchestrate the opening chorus of his opera William Ratcliff and by Alexander Dargomyzhsky, who was close to death, to orchestrate his opera The Stone Guest.[15]

In the fall of 1871, Rimsky-Korsakov moved into his brother's former apartment, inviting Mussorgsky to be his roommate. The working arrangement they agreed upon was that Mussorgsky used the piano in the mornings while Rimsky-Korsakov either copied or orchestrated something out. Mussorgsky left for his civil service job at noon. This left afternoons for Rimsky-Korsakov to use the piano. Time in the evenings was allotted by mutual agreement.[15] "That autumn and winter the two of us accomplished a good deal," Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, "with constant exchange of ideas and plans. Mussorgsky composed and orchestrated the Polish act of Boris Godunov and the folk scene 'Near Kromy.' I orchestrated and finished my Maid of Pskov."[17]

Professor

Also in 1871, Rimsky-Korsakov became Professor of Practical Composition and Instrumentation (orchestration) at the St. Petersburg Conservatory,[18] as well as leader of the Orchestra Class[15] Mikhaíl Azanchevsky, who had taken over that year as director,[15] had wanted new blood to freshen up teaching in those subjects.[19] Balakirev, who had formerly opposed academicism with tremendous vigor,[20] had encouraged him to assume the post.[21] Painfully aware of his technical shortcomings,[22] he soon became "possibly its very best pupil, judging by the quantity and value of the information it gave me!"[23] To prepare himself for his teaching role, in an attempt to stay at least one step ahead of his students, he took a three-year sabbatical from composition and assiduously studied at home, teaching himself from textbooks[24] and following a strict regimen of contrapuntal exercises, fugues, chorales and a cappella choruses.[25] He eventually became an excellent teacher and a fervent believer in academic training.[26][23][27] He also became compelled to revise everything he had composed prior to 1874, even highly acclaimed works such as Sadko and Antar.[25] This process of perfecting earlier works would remain with him throughout the rest of his life.[25]

Marriage

With Rimsky-Korsakov's professorship came financial security.[28] This encouraged him to settle down and to start a family.[28] In December 1871 he proposed to Nadezhda Purgold. They married in July 1872;[28] Mussorgsky was his best man. The Rimsky-Korsakovs would eventually have seven children. One of their sons, Andrei, would become a musicologist, marry the composer Yuliya Veysberg and write a multi-volume study of his father's life and work.

Nadezhda was to become a musical as well as domestic partner with her husband, much as Clara Schumann had been with her own husband Robert.[28] Beautiful, capable, strong-willed and far better trained musically than her husband at the time they married,[29] she proved a good and most demanding critic of his work; her influence over him in musical matters was strong enough for Balakirev and Stasov to wonder sometimes whether she was leading him astray from their musical preferences.[25] She also arranged the second version of Antar for piano four hands in 1875.[30] This arrangement was published by Bessel.[30] (She had arranged the original version of Antar for piano four hands in 1869—70, before she married Rimsky-Korsakov.)[31]

Inspector of bands

Even while a professor at the conservatory, Rimsky-Korsakov remained in active service as a naval officer. In the spring of 1873, the navy remedied this situation, allowing him to resign his commission by creating the post of Inspector of Naval Bands.[32] He was to inspect naval bands throughout Russia, supervising the bandmasters and their appointments, repertoire and quality of instruments. He would also be in charge of a complement of music students who would also hold navy fellowships at the conservatory. He was to write a study program for these students and to act as an intermediary between the navy and the conservatory. The post came with a promotion to Collegiate Assessor, a civilian rank. Rimsky-Korsakov was kept on the navy payroll and listed on the roster of the Chancellery of the Navy Department. Otherwise, he would no longer be considered under military service.[33]

Rimsky-Korsakov applied himself with zeal on his duties[32] while also indulging in a long-standing desire to familiarize himself with the construction and playing technique of orchestral instruments.[34] He delved into the subject headlong, purchasing and learning to play a number of instruments.[35] These studies in turn prompted him to write a textbook on orchestration.[34] He used the privileges of rank to freely exercise and expand upon his knowledge, orchestrating for military bands and arranging a number of works by other composers.[36]

In March 1884, an Imperial Order abolished the navy office of Inspector of Bands, and Rimsky-Korsakov was relieved of his duties.[32] "Accordingly," he wrote, "my government service was confined exclusively to the Chapel—that is, the court Department."[37] He worked under Balakirev in the Court Chapel as a deputy. This post gave him the chance to study Russian Orthodox church music. He wrote his textbook on harmony for the classes he taught there,[38] after finding Tchaikovsky's book on the subject unsatisfactory.[39] He worked at the chapel until 1894.[40]

Flailing in counterpoint

His studies and change in attitude on music education brought Rimsky-Korsakov the scorn of his fellow nationalists. They felt he was throwing away his Russian heritage to compose fugues and sonatas.[27] After striving "to crowd in as much counterpoint as possible" into his Third Symphony,[41] he applied his newly acquired knowledge to chamber works in which he adhered strictly to classical models. These included a string sextet, a string quartet in F minor and a quintet for flute, clarinet, horn, bassoon and piano. The reaction of his fellow nationalists did not help. They showed little enthusiasm for the Third Symphony, less still for the quartet.[42] He wrote, "[T]hey began, indeed, to look down upon me as one on the downward path."[42] Worse still was Anton Rubinstein, the nationalists' arch-nemesis, commenting after hearing the quartet that now Rimsky-Korsakov "might amount to something" as a composer.[42]

Folk song, Glinka and Gogol

Two projects helped Rimsky-Korsakov focus on less academic music-making. The first involved Russian folk songs, in which he took a renewed interest in 1874, creating two collections[43] that he credited as influencing him greatly as a composer.[44] The second project was the editing of Mikhail Glinka's orchestral scores in collaboration with Balakirev and Anatoly Lyadov. Both these tasks had a therapeutic effect on Rimsky-Korsakov.[32]

In the summer of 1877 he thought increasingly about the short story "May Night" by Nikolai Gogol. The story had long been a favorite of his, and his wife had encouraged him to write an opera based on it from the day of their betrothal, when they had read it together.[45] While some musical ideas for such a work had come earlier, now they came with ever greater persistence. By winter May Night began taking more of his attention; in February he started writing in earnest. By early November, the opera was finished.[43]

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that May Night was of great importance because, despite his extensive use of counterpoint in the work, he "cast off the shackles of counterpoint" (italics Rimsky-Korsakov).[46] He wrote it in a folk-like melodic idiom, with singing melody and phrase replacing inexpressive recitative, and scored with a transparent operatic orchestration much like the style of Glinka.[32] Nevertheless, despite his next opera, The Snow Maiden, coming with an ease and rapidity he had not known before,[47] Rimsky-Korsakov was intermittently paralyzed creatively, with his progress as a composer coming to a standstill from 1881 to 1888.[48] He kept busy by editing Mussorgsky's works and completing Borodin's Prince Igor.[48]

Russian Symphony Concerts

Rimsky-Korsakov became acquainted with capitalist and budding music patron Mitrofan Belyayev (M. P. Belaieff) at the weekly "quartet Fridays" ("Les Vendredis") held at Belyayev's home. Belyayev, who had already taken a keen interest in the musical future of the teenage Alexander Glazunov, rented out a hall and hired an orchestra in 1884 to play Glazunov's First Symphony plus an orchestral suite Glazunov had just composed. This concert and a rehearsal the previous year gave Rimsky-Korsakov the idea of offering several concerts per year featuring Russian compositions, a prospect to which Belyayev was amenable. The Russian Symphony Concerts were inaugurated during the 1886-1887 season, with Rimsky-Korsakov sharing conducting duties.[49]

He finished his revision of Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain and conducted it at the opening concert.[50] The concerts also coaxed him out of his creative drought, with his writing Scheherazade, Capriccio espagnol and the Russian Easter Overture specifically for them.[48] He noted that these three works "show a considerable falling off in the use of contrapuntal devices ... [replaced] by a strong and virtuoso development of every kind of figuration which sustains the technical interest of my compositions."[51]

Exclusively opera

What would become the climactic event in Rimsky-Korsakov's creative life was the visit to St. Petersburg of Angelo Neumann's traveling "Richard Wagner Theater." This company gave four cycles of Der Ring des Nibelungen there under the direction of Karl Muck in March 1889.[52] The Five had long ignored Wagner's music. Nonetheless, Rimsky-Korsakov was impressed when he heard the Ring.[53] Attending all the rehearsals with Glazunov and following with the score, he was astonished with Wagner's mastery of orchestration. After hearing these performances, Rimsky-Korsakov devoted himself almost exclusively to composing operas for the rest of his creative life. Wagner's use of the orchestra began influencing Rimsky-Korsakov's orchestration, as well,[52] beginning with the arrangement of the polonaise from Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov that he made for concert use in 1889.[54]

Later years

In 1892 Rimsky-Korsakov suffered a second creative drought,[48] brought on by bouts of depression and alarming physical symptoms—rushes of blood to the head, confusion, memory loss and unpleasant obsessions.[55] The medical diagnosis was neurasthenia.[55] Another cause for the depression may have been the serious illnesses of his wife and one of his sons from diphtheria in 1890, the deaths of his mother and youngest child plus the onset of the prolonged, ultimately fatal illness of his second youngest child.[55] He resigned from both the Russian Symphony Concerts and the Court Chapel.[55] He also considered giving up composition permanently.[48] Making third versions of the musical tableau Sadko and the opera The Maid of Pskov, he closed his musical account with the past, leaving none of his major works before May Night in their original form.[52]

Another death, ironically, brought about a creative renewal.[55] The passing of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in late 1893 presented a two-fold opportunity — to write for the Imperial Theaters and to compose an opera based on Nikolai Gogol's short story "Christmas Eve", a work on which Tchaikovsky had based his opera Vakula the Smith. Rimsky-Korsakov's Christmas Eve was a success and restored his creativity. He completed an opera approximately every 18 months — a total of 11 between 1893 and 1908.[48] He also started and abandoned another draft of his treatise on orchestration.[56] He made a third attempt in the last four years of his life.[56] He nearly finished it before his death (his son-in-law Maximilian Steinberg completed it posthumously in 1912), illustrating his text with more than 300 examples from his work.[56] Rimsky-Korsakov's scientific treatment of orchestration set a new standard for texts of its kind.[56]

In 1905, approximately 100 conservatory students were expelled for taking part in the February Revolution.[57] Rimsky-Korsakov sided with the students and was removed from his professorship.[57] A student production of his opera Kaschei the Immortal was followed not with the scheduled concert but with a political demonstration.[58] A police ban on Rimsky-Korsakov's work followed.[58]An immediate wave of outrage to the ban arose throughout Russia and abroad; liberals and intellectuals deluged the composer's residence with letters of sympathy.[59] Several faculty members resigned in protest, including Glazunov and Lyadov.[57] Eventually, over 300 additional students walked out of the conservatory in solidarity with Rimsky-Korsakov.[60] By December he had been reinstated, but the political controversy continued with his opera The Golden Cockerel.[60] Its implied criticism of monarchy, Russian imperialism and the Russo-Japanese War gave it little chance of passing the censors.[60] The premiere was delayed until 1909, after the composer's death.[60] Even then, it was performed in an adapted version.[60]

Beginning around 1890, Rimsky-Korsakov suffered from angina.[55] While this ailment initially wore him down gradually, the stresses concurrent with the February Revolution and its aftermath greatly accelerated its progress. After December 1907, his illness became severe, preventing all work.[61] He died in Lyubensk in 1908, and was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St. Petersburg.[62]

Legacy

Compositions

Rimsky-Korsakov was a prolific composer, and as a perpetual self-critic, he revised all of his orchestral works up to and including his Third Symphony—some, like Antar and Sadko, more than once.[63] These revisions cover the gamut from minor changes of tempo, phrasing and instrumental detail to wholesale transposition and complete recomposition.[64]

Rimsky-Korsakov continued to be interested in harmonic experiments and the exploration of new idioms, but this interest was coupled with an abhorrence of excess. Taking Glinka and Liszt as models, he progressed considerably in his use of whole tone and octatonic scales, developing them both in the "fantastic" sections of his operas. However, he kept his tendency to experiment under constant control. The more radical his harmonies became, the more he attempted to control them with strict rules—applying his "musical conscience," as he called it. In this sense, he was both a progressive and a conservative composer.[65]

Operas

While Rimsky-Korsakov is best known for in the West for his orchestral works, his operas far outweigh them in importance, offering a far wider variety of orchestral effect as well as his finest vocal writing.[58] Subjects range from historical melodramas (The Tsar's Bride) to folk operas (May Night) to fairytales and legends (Snowmaiden, Kashchey the Immortal and The Tale of Tsar Saltan).[66] Despite all his efforts as an operatic composer, however, Rimsky-Korsakov suffered from the seemingly fatal flaw of writing music that lacked dramatic power.[67] This may have been a conscious decision on the composer's part, as he repeatedly stated in his scores that he felt operas were first and foremost musical works rather than mainly dramatic ones. Ironically, the operas succeed in most cases by being deliberately non-dramatic.[67] Toward this end he devised a dual musical language—diatonic and lyrical music much like Russian folk music for the "real" human characters and chromatic, highly artificial music for the "unreal" magical beings.[67] As Harold C. Schonberg phrases it, the operas "open up a delightful new world, the world of the Russian East, the world of supernaturalism and the exotic, the world of Slavic pantheism and vanished races. Genuine poetry suffuses them, and they are scored with brilliance and resource."[68]

Orchestral works

The purely orchestral works are mainly programmatic in nature, more so if we take at face value Rimsky-Korsakov's comment, "To me, even a folk theme has a programme of sorts."[3] They show the dual influence of Balakirev and Liszt[3] and continue the musical ideals espoused by The Five, such as in the use of liturgical themes in the Russian Easter Festival Overture; this work also follows the design and plan of Balakirev's Second Overture on Russian Themes. Capriccio espagnol is based on folk song but its structure is more rhapsodic. Schereherazade became the best-known expression of Russian orientalism; with the sultan introduced with a robust theme in the brass and Schereherazade in the arabesques of a violin solo, the paradigm between barbarous despotism and feminine seduction is set forth at once. Her theme links this work with the orientalism of The Five while being in itself very closely related to Balakirev's Tamara.[3][69] Another exercise in orientalism is the symphonic poem Night on Mount Triglav, a symphonic rearrangement of Act III of the opera Mlada.[69]

Rimsky-Korsakov's works in this category are especially noteworthy for their orchestration. Though this is true even of early works such as Sadko and Antar, their sparer textures pale compared to the luxuriance of the most popular works of the 1880s.[3] While a principle of highlighting "primary hues" remained in place, it was augmented in the later works by a sophisticated cachet of orchestral effects, some of which were gleaned from other composers such as Wagner but many of which were invented by Rimsky-Korsakov himself.[3] As a result, these works resemble brightly-colored mosaics, striking in their own right and often scored with a juxtaposition of pure orchestral groups.[70] The final tutti of Schereherazade is a prime example of this scoring. The theme is assigned to trombones playing in unison. This is accompanied by a combination of string patterns. Meanwhile, another pattern alternates with chromatic scales in the woodwinds and a third pattern of rhythms is played by percussion.[71]

Smaller-scaled works

Smaller-scaled works include dozens of art songs, arrangements of folk songs, some chamber and piano music, and a considerable number of choral works, both secular and for Russian Orthodox Church service, including settings of portions of the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom (the latter despite his staunch atheism)[72][73][74]

Students

In his decades at the Conservatory, Rimsky-Korsakov taught many composers who would later find fame, including Alexander Glazunov, Alexander Spendiaryan, Sergei Prokofiev, Igor Stravinsky, Ottorino Respighi, Witold Maliszewski and Artur Kapp. Other students included the music critic and musicologist Alexander Ossovsky, and the composer Lazare Saminsky.[75]

Rimsky-Korsakov felt talented students needed little. Show them everything needed in harmony and counterpoint, direct them in understanding the forms of composition. Give them a year or two of systematic study in the development of technique, a few exercises in free composition and orchestration, and a good knowledge of the piano. Provided these steps were all done properly, studies would then be over.[76]

He carried this attitude into his conservatory classes. Conductor Nikolai Malko remembered that Rimsky-Korsakov began the first class of the term by saying, "I will speak, and you will listen. Then I will speak less, and you will start to work. And finally I will not speak at all, and you will work."[77] Malko added that his class followed exactly this pattern. "Rimsky-Korsakov explained everything so clearly and simply that all we had to do was to do our work well."[77]

Rimsky-Korsakov would sit at the piano in class, looking through all the exercises in counterpoint his students had brought. He played endless preludes, fugues, canons and arrangements. However, he refused to review a student's work if it was written in pencil. "I do not wish to go blind because of you," he would declare. (Dmitri Shostakovich would also insist that his composition students write their scores in ink.)[78]

Because of Rimsky-Korsakov's fame, his classes were large. This irritated the 15-year-old Prokofiev, who wanted the master's undivided attention and had trouble breaking through the crowd. Nevertheless, he admitted that those students who knew how much they could learn from Rimsky-Korsakov got the benefit despite the crowding.[79]

Editing "The Five"'s work

Rimsky-Korsakov's efforts in editing works by fellow members of The Five are significant. This effort was a practical extension of the collaborative atmosphere of The Five during the 1860s and 1870s, when they heard each other's compositions in progress and even worked together on them. It was also an effort to save works that would either languish unheard or become lost entirely. These include the completion of Alexander Borodin's opera Prince Igor (with Alexander Glazunov),[48] orchestration of passages from César Cui's William Ratcliff for the first production in 1869, and the complete orchestration of Alexander Dargomyzhsky's swan song, The Stone Guest.[15]

While this effort is laudable, it is also not without controversy, especially in the case of works by Modest Mussorgsky. After Mussorgsky's death in 1881, Rimsky-Korsakov revised and completed several of Mussorgsky's works for publication and performance. In some cases these versions helped to spread Mussorgsky's works throughout Russia and to the West. However, in going over the scores of his friends, Rimsky-Korsakov allowed his "musical conscience" to dictate his editing, avoiding what he considered musical over-experimentation or bad form, just as he allowed it to control his own composing.[80] Because of this tendency, he has been accused of pedantry in "correcting", among other things, matters of harmony. Rimsky-Korsakov may have foreseen this when he wrote this statement:

If Moussorgsky's compositions are destined to live unfaded for fifty years after their author's death (when all his works will become the property of any and every publisher), such an archeologically accurate edition will always be possible, as the manuscripts went to the Public Library on leaving me. For the present, though, there was need of an edition for performances, for practical artistic purposes, for making his colossal talent known, and not for the mere studying of his personality and artistic sins.[81]

Time seems to have proven Rimsky-Korsakov correct. Mussorgsky's musical style, once considered unpolished, is now valued for its originality. While Rimsky-Korsakov's arrangement of Night on Bald Mountain is still the version generally performed today, some of Rimsky-Korsakov's other revisions, such as that of Boris Godunov, have been replaced by Mussorgsky's original versions.[2]

Folklore and pantheism

Rimsky-Korsakov may have saved the most personal side of his creativity for his approach to Russian folklore.[82] Folklorism as practiced by Balakirev and the other members of 'The Five" had been based largely on the protyazhnaya dance song.[82] Protyazhnaya literally meant "drawn-out song," or melimatically elaborated lyric song.[83] The characteristics of this song exhibit extreme rhythmic flexibility, an asymmetrical phrase structure and tonal ambiguity.[83] After composing May Night, however, Rimsky-Korsakov was increasingly drawn to "Calendar songs."[82] These songs were written for specific ritual occasions.[82] The appeal of these songs for him was more than purely musical.[82] Calendar songs, which formed a part of rural customs, echoed old Slavic paganism, and the pantheistic world of folk rites was what interested him most in folk music, even in his days with "The Five."[82]

Rimsky-Korsakov's interest in pantheism was whetted by the folkloristic studies of Alexander Afanasyev.[82] That author's standard work, The Poetic Outlook on Nature by the Slavs, became Rimsky-Korsakov's pantheistic bible.[82] The composer first applied Afanasyev's ideas in May Night, in which he helped fill out Gogol's story by using folk dances and calendar songs.[82] He went further down this path in The Snow Maiden.[82] There he makes extensive use of seasonal calendar songs and khorovodi (ceremonial dances) in the folk tradition.[84]

Books

His autobiography and his books on harmony and orchestration have been translated into English and published. They provide remarkable insights into his life and work. Two books he started in 1892 but left unfinished were a comprehensive text on Russian music and a manuscript, now lost, on an unknown subject.[85]

- My Musical Life. [Летопись моей музыкальной жизни – literally, Chronicle of My Musical Life.] Trans. from the 5th rev. Russian ed. by Judah A. Joffe; ed. with an introduction by Carl Van Vechten. London: Ernst Eulenburg Ltd, 1974.

- Practical Manual of Harmony. [Практический учебник гармонии.] First published, in Russian, in 1885. First English edition published by Carl Fischer in 1930, trans. from the 12th Russian ed. by Joseph Achron. Current English ed. by Nicholas Hopkins, New York, NY: C. Fischer, 2005.

- Principles of Orchestration. [Основы оркестровки.] Begun in 1873 and completed posthumously by Maximilian Steinberg in 1912, first published, in Russian, in 1922 ed. by Maximilian Steinberg. English trans. by Edward Agate; New York: Dover Publications, 1964 ("unabridged and corrected republication of the work first published by Edition russe de musique in 1922").

Bibliography

- Abraham, Gerald, ed. Stankey Sadie, "Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolay Andreyevich," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 20 vols. (London: MacMillian, 1980). ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Abraham, Gerald. Rimsky-Korsakov: a Short Biography. London: Duckworth, 1945; rpt. New York: AMS Press, 1976. Later ed.: Rimsky-Korsakov. London: Duckworth, 1949.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840-1874 (New York, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1978). ISBN 0-393-07535-2.

- Calvocoressi, M.D. and Gerald Abraham, Masters of Russian Music (New York: Tudor Publishing Company, 1944). ISBN n/a.

- Figes, Orlando, Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002). ISBN 0-8050-5783-8 (hc.)

- Frolova-Walker, Marina, ed. Stankey Sadie, "Rimsky-Korsakov. Russian family of musicians. (1) Nikilay Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition, 29 vols. (London: MacMillian, 2001). ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Griffiths, Steven. A Critical Study of the Music of Rimsky-Korsakov, 1844-1890. New York: Garland, 1989.

- Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995). ISBN 0-679-42006-1.

- Leonard, Richard Anthony, A History of Russian Music (New York: MacMillian, 1957). Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 57-7295.

- Maes, Francis, tr. Pomerans, Arnold J. and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Poznansky, Alexander Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man Lime Tree (1993) ISBN 0-413-45721-4 (hb), ISBN 0-413-45731-1 (pb).

- Rimsky-Korsakov, A.N. Н.А. Римский-Корсаков: жизнь и творчество [N.A. Rimsky-Korsakov: Life and Work]. [5 vols.] Москва: Государственное музыкальное издательство, 1930.

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai, Letoppis Moyey Muzykalnoy Zhizni (St. Petersburg, 1909), published in English as My Musical Life (New York: Knopf, 1925, 3rd ed. 1942). ISBN n/a.

- Richard Taruskin. "The Case for Rimsky-Korsakov," Opera News, vol. 56, nos. 16 and 17 (1991–2), pp. 12–17 and 24-29, respectively.

- Schonberg, Harold C. Lives of the Great Composers (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. 1997).

- Volkov, Solomon, tr. Antonina W. Bouis, St. Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, 1995). ISBN 0-02-874052-1.

- Volkov, Solomon, tr. Antonina W. Bouis, Testimony: The memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich (New York: Harper & Row, 1979). ISBN 0-06-014476-9.

- Yastrebtsev, Vasily Vasilievich. Reminiscences of Rimsky-Korsakov. Ed. and trans. by Florence Jonas. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985. (Note: this is heavily abridged.)

Richard Beattie Davis `The Beauty of Belaieff` London 2008 ISBN 978-1-905912-14-8 http://www.gclefpublishing.com

Florida Atlantic University Richard Beattie Davis Music Collection http://www.library.fau.edu/depts/spc/davis.htm

References

- ^ a b Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:34.

- ^ a b Maes, 115.

- ^ a b c d e f Frolova-Walker, 'New Grove (2001), 21:409.

- ^ a b Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:27.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 11.

- ^ a b c d e Frolova-Walker, New Grove (2001), 21:400.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 16.

- ^ Calvocoressi, M.D. and Gerald Abraham, Masters of Russian Music (New York: Tudor Publishing Company, 1944), 342.

- ^ Abraham, New Grove (1980), 2:28; Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 18.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 38.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 22.

- ^ This is sometimes claimed to be the first symphony by a Russian, but Anton Rubinstein composed his own first symphony in 1850.

- ^ Abraham, New Grove (1980), 2:28; Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 42.

- ^ Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:28.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 57.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 123.

- ^ Frolova-Walker, New Grove (2001), 21:401.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 116.

- ^ Maes, 39.

- ^ Maes, 169—170.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 117.

- ^ a b Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 119.

- ^ Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:29.

- ^ a b c d Frolova-Walker, New Grove (2001), 21:401.

- ^ Maes, 170.

- ^ a b Schonberg, Harold C., Lives of the Great Composers, 363.

- ^ a b c d Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:28

- ^ Abraham, New Grove (1980)16:28—29.

- ^ a b Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 156.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 109.

- ^ a b c d e Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:29.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 135—136.

- ^ a b Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 136.

- ^ Leonard, 148.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 141—142.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 269 + footnote 12.

- ^ Leonard, Richard Anthony, A History of Russian Music (New York: MacMillian, 1957), 149.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 271,

- ^ Frolova-Walker, New Grove (2001), 8:404; Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 335

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 133.

- ^ a b c Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 151.

- ^ a b Frolova-Walker, New Grove (2001), 21:402. Cite error: The named reference "mfw21402" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 166.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 188—189.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 208.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 235.

- ^ a b c d e f g Maes, 171.

- ^ Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:29—30

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 281.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 296.

- ^ a b c Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:30.

- ^ Maes, 176—177.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 298.

- ^ a b c d e f Abraham, 'New Grove, 16:31.

- ^ a b c d Leonard, 149.

- ^ a b c Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 414.

- ^ a b c Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:32.

- ^ Leonard, 167.

- ^ a b c d e Maes, 178.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, Preface xxiii.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical life, 461.

- ^ Abraham, Slavonic, 197.

- ^ Abraham, Slavonic, 197-198.

- ^ Maes, 180.

- ^ Maes, 176—180.

- ^ a b c Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:33.

- ^ Schonberg, 364.

- ^ a b Maes, 175—176.

- ^ Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:32.

- ^ Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:32—33.

- ^ Abraham, Gerald, The New Grove Russian Masters 2 (New York: W.W. Norton and company, 1986), 27.

- ^ (Abraham, Gerald (1936). "XIII. Kitezh". Studies in Russian Music. London: William Reeves / The New Temple Press. p. 288.)

- ^ (Morrison, Simon (2002). "2. Rimsky-Korsakov and Religious Syncretism". Russian Opera and the Symbolist Movement. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 116–117, 168–169. ISBN 0-520-22943-6.)

- ^ Schonberg, 365.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, Letopis [Chronicle], 34.

- ^ a b Malko, M.A., Vospominaniia. Stat'i. Pisma [Reminiscences. Articles. Letters] (Lenningrad, 1972), 49.

- ^ Volkov, St. Petersburg, 345.

- ^ Prokofiev, S.S., Materialy. Dokumenty. Vospominaniia [Materials. Documents. Reminiscences] (Moscow, 1961), 138.

- ^ Maes, 181.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 249.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Maes, 187.

- ^ a b Maes, 65.

- ^ Maes, 188.

- ^ Leonard, 150.

External links

Films

- Great Russian Composers: Nicolay Rimsky-Korsakov at IMDb (2004)

- Римский-Корсаков at IMDb (Soviet biographical film from 1952)

- Song of Scheherazade at IMDb

Scores

- Free scores by Rimsky-Korsakov at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Template:IckingArchive

Other

- The Rimsky-Korsakov Home Page

- Principles of Orchestration full text with "interactive scores."