Feral child

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

A feral child (feral, wild, or undomesticated) is a human child who has lived isolated from human contact from a very young age, and has no (or little) experience of human care, loving or social behavior, and, crucially, of human language.[1] Some feral children have been confined by people (usually their own parents); in some cases this child abandonment was due to the parents' rejection of a child's severe intellectual or physical impairment. Feral children may have experienced severe child abuse or trauma before being abandoned or running away. Others are alleged to have been brought up by animals; some are said to have lived in the wild on their own. Just over a hundred incidents have been reported in English.[2]

When completely brought up by animals, the feral child exhibits behaviors (within physical limits) almost entirely like those of the particular care-animal, such as its fear of or indifference to humans. The term Mowgli Syndrome has been applied. These cases have been investigated by researchers and scientists in the fields of psychology and sociology.

Legends

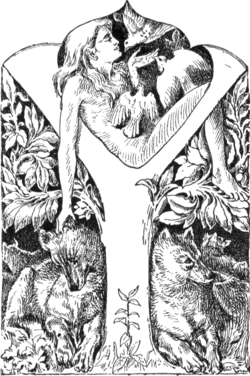

Myths, legends, and fictional stories have depicted feral children reared by wild animals such as wolves and bears. Famous examples include Ibn Tufail's Hayy, Ibn al-Nafis' Kamil, Rudyard Kipling's Mowgli, Edgar Rice Burroughs's Tarzan and his son Korak, and the legends of Enkidu and Romulus and Remus.

Legendary and fictional feral children are often depicted as growing up with relatively normal human intelligence and skills and an innate sense of culture or civilization, coupled with a healthy dose of survival instincts; their integration into human society is made to seem relatively easy.

These mythical children are often depicted as having superior strength, intelligence and morals compared to "normal" humans, the implication being that because of their upbringing they represent humanity in a pure and uncorrupted state: similar to the noble savage.

The subject is treated with a certain amount of realism in François Truffaut's 1970 film L'Enfant Sauvage (UK: The Wild Boy, US: The Wild Child), where a scientist's efforts in trying to rehabilitate a feral boy meet with great difficulty.

Reality

In reality, feral children lack the basic social skills which are normally learned in the process of enculturation. For example, they may be unable to learn to use a toilet, have trouble learning to walk upright and display a complete lack of interest in the human activity around them. They often seem mentally impaired and have almost insurmountable trouble learning a human language. The impaired ability to learn language after having been isolated for so many years is often attributed to the existence of a critical period for language learning, and taken as evidence in favor of the Critical Period Hypothesis.

It is almost impossible to convert a child who became isolated at a very young age into a relatively normal member of society and such individuals need close care throughout their lives. When they are "discovered", feral children tend to become the subject of lively scientific and media interest. Once the excitement dies down and their limitations in terms of learning culture and social behavior become obvious, frustration can set in and they often spend the rest of their lives being passed from one caregiver to another. It is common for them to die young, though their potential lifespan if they had been left in the wild is difficult to know.

There is little scientific knowledge about feral children. One of the most well-known examples, the "detailed diaries" of Reverend Singh who claimed to have discovered Amala and Kamala (two girls who had been "brought up from birth by wolves") in a forest in India, has been proven a fraud to obtain funds for his orphanage. Bruno Bettelheim states that Amala and Kamala were born mentally and physically disabled.[3]

Ancient reports

Herodotus, the historian, wrote that Egyptian pharaoh Psammetichus I (Psamtik) sought to discover the origin of language by conducting an experiment with two children. Allegedly, he gave two newborn babies to a shepherd, with the instructions that no one should speak to them, but that the shepherd should feed and care for them while listening to determine their first words. The hypothesis was that the first word would be uttered in the root language of all people. When one of the children cried "becos" (a sound quite similar to the bleating of sheep) with outstretched arms the shepherd concluded that the word was Phrygian because that was the sound of the Phrygian word for bread. Thus, they concluded that the Phrygians were an older people than the Egyptians.

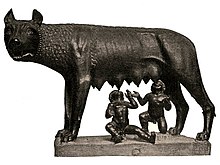

Legend has it that Romulus and Remus, twin sons of Rhea Silvia and Mars, were raised by wolves. Rhea Silvia was a priestess, and when it was found that she had been pregnant and had had children, the local King Amulius ordered her to be buried alive and for the children to be killed. The servant who was given the order set them in a basket on the Tiber river instead and the children were taken by Tiberinus, the river god, to the shore where a she-wolf found them and raised them until they were discovered as toddlers by a shepherd named Faustulus. He and his wife Acca Larentia, who had always wanted a child but never had one, raised the twins, who would later figure prominently in the events leading up to the founding of Rome (named after Romulus, who eventually kills Remus to have the city founded on the Palatine Hill rather than the Aventine Hill).

Documented cases

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2008) |

Following the 2008 disclosure by Belgian newspaper Le Soir[4] that the bestselling book Misha: A Mémoire of the Holocaust Years and movie Survivre avec les loups (Survival with Wolves) was a media hoax, the French media debated the credulity with which numerous cases of feral children have been blindly accepted. Though there are numerous books on these children, almost none of them have been based on archives, the authors instead using rather dubious second or third-hand printed information. According to the French surgeon Serge Aroles, who wrote a general study of feral children based on archives (L'Enigme des Enfants-loups or The Enigma of Wolf-children, 2007), almost all of these cases are scandalous swindles or totally fictitious stories.

- Hessian wolf-children (1304, 1341 and 1344).[citation needed]

- The Bamberg boy, who grew up among cattle (late 1500s).[citation needed]

- The Irish boy brought up by sheep, reported by Nicolaes Tulp in his book Observationes Medicae (1672). Serge Aroles gives evidence that this boy was a severely disabled boy exhibited for money.

- The three Lithuanian bear-boys (1657, 1669, 1694). Serge Aroles shows from the archives of the Queen of Poland (1664-1688) that these are false. There was only one boy, found in the forests in spring 1663 and then brought to Poland's capital.

- The girl of Oranienburg (1717).[5]

- The two Pyrenean boys (1719).[citation needed]

- Peter the Wild Boy of Hamelin (1724). Mentally handicapped boy, affected with anomalies of the tongue and the fingers. He lived only one year in the wild.

- Marie-Angélique Memmie Le Blanc, the Wild Girl of Songy, also known as the Wild Girl of Champagne (France, 1731). Serge Aroles unearthed hundreds of documents concerning her, and published 30 of them in a 2004 biography. This is the only case of a child having survived 10 years in the forests (from November 1721 to September 1731), and the only feral child who succeeded in a complete intellectual rehabilitation, having learned to read and to write. Unfortunately, all the archives are in French, and almost all the books and articles written in English are wrong: Marie-Angelique was not 10 years old when she was captured, but 19 years old; she did not die "poor at the age of thirty", but she died rich at the age of 63 (15 December 1775); she was not an Eskimo but an Amerindian from Wisconsin (then a French colony); she was brought to France by a lady living in Canada and then escaped into the woods of Provence in 1721.

- The bear-girl of Krupina, Slovakia (1767). Serge Aroles found no traces of her in the Krupina archives.

- The teenager of Kronstadt (1781).[6] According to the Magyar (Hungarian) document published by Serge Aroles, this case is a hoax : the boy, mentally handicapped, had a goitre and was exhibited for money.

- Victor of Aveyron (1797), portrayed in the 1969 movie, The Wild Child (L'Enfant sauvage), by François Truffaut. Once more, Serge Aroles gave evidence that this famous case was not a genuine feral child.

- Kaspar Hauser (early 1800s), portrayed in the 1974 film by Werner Herzog The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle).[7]

- Amala and Kamala, found in 1920 near Midnapore, Calcutta region, India

- Shuckskinder, Zell Am See, Austria (c. 1930) A child reported to be seen by locals of the Saalbach-Hinterglem region of the Austrian Alps. No confirmed photographs, nor identifications were ever made, but some locals believed the child was mentally disabled. Physiologist Rebecca Gowing and mountaineer Jamie Gates traced the roots of this myth-child to the Shucksmith family, who had a son registered as partially disabled living on the Austro-Hungarian border, who was lost from records.[citation needed]

- Ramu, Lucknow, India, (1954), taken by a wolf as a baby, raised until the age of seven.[8] Aroles made inquiries on the scene and classifies this as another hoax.

- Syrian Gazelle Boy: A boy aged around 10 was found in the midst of a herd of gazelles in the Syrian desert in the 1950s, and was only caught with the help of an Iraqi army jeep, because he could run at speeds of up to 50 km/h.[9] This is a hoax, as are all the gazelle-boys (see below).

- Saharan Gazelle Boy (1960): found in Rio de Oro in the Spanish Sahara, written about by Basque traveller Jean-Claude Auger, using the pseudonym Armen in his 1971 book L'enfant sauvage du grand desert, translated as Gazelle Boy.[10] When Serge Aroles made inquiries concerning this case in 1997, gathering testimonies in Mauritania, Armen himself admitted that he had written "a book of fiction".

- Genie, Los Angeles, California, discovered 1970.[11] Confined to one room by her father.

- Robert (1982). He lost his parents in the Ugandan Civil War at the age of three, when Milton Obote's looting and murdering soldiers raided their village, around 50 miles (80 km) from Kampala. Robert then lived in the wild, presumably with vervet monkeys, for three years until he was found by soldiers.[12]

- James Goodfellow (1983). He was found in Brazil, having been raised by wolves. He proceeded to be the alpha male within the pack. He ran on all fours and howled in the night. He was seen cleaning himself with his tongue and hands, very common among feral children.[citation needed]

- Baby Hospital (1984). This seven-year-old girl was found by an Italian missionary in Sierra Leone. She had apparently been brought up by apes or monkeys. Baby Hospital was unable to stand upright and crawled instead of walking, and ate directly from her bowl without using her hands. She made the chattering noises of apes or monkeys. Baby Hospital's arms and hands were reported to be well developed, but not her leg muscles. She resisted attempts to civilise her, instead spending much of her time in an activity that is very unusual for feral children: crying.[13]

- Saturday Mthiyane (or Mifune) (1987). A boy of around five who spent a year in the company of monkeys in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa.[14]

- Oxana Malaya, Ukraine, (1990s). Raised with dogs until the age of nine.[15]

- Daniel, Andes Goat Boy (1990). Found in Peru, and was said to have been raised by goats for eight years.[16]

- John Ssebunya, Uganda, (1991) raised by monkeys for several years in the jungle.[17][18]

- Belo, the Nigerian Chimp Boy (1996) about two years of age, raised by chimpanzees for a year and a half.[19]

- Ivan Mishukov (1998). Found near Moscow, raised by dogs for two years, and had risen to being "alpha male" of the pack.[20]

- Edik, Ukraine (1999). Edik was found by social workers apparently living with stray dogs in an apartment.[21]

- Alex the Dog Boy (2001). Found in Talcahuano, Chile.[22]

- Traian Căldărar, Romania (2002). Lived for three years with wild dogs in the wilderness.[23]

- Andrei Tolstyk (2004) of Bespalovskoya, near Lake Baikal, Russia, abandoned by parents, to be raised by a guard dog.[24]

- Cambodian jungle girl, Cambodia, (2007), alleged to be Rochom P'ngieng, who lived 19 years in the jungle.[25] Other sources questioned these claims.[26]

- Name Unknown, Uzbekistan, (2007) found after eight years.[27]

- Amy G, Bansko, Bulgaria (2007). She was found in a mountain area where she had been raised by stray dogs. She was unable to communicate and appears to have lived on wild berries and rats.[citation needed]

- Lyokha, Kaluga, Central Russia (December 2007). He had been living with a pack of wolves, had typical wolflike behavior and reactions. He was unable to speak any human language. Taken to a Moscow hospital, he received some medical treatment, a shower and nailtrim and several meals before escaping from the building. He is believed to still be in the wild.[28]

- Danielle Crockett, Florida, United States (2007-2008). Dani had been locked in her room and deprived of human interaction for the first 7 years of her life. She was found and adopted and is currently undergoing efforts to acclimate her to human conditioning including learning English and effective communication.[29][30][31]

See also

- Child development

- Cognitive ethology

- Language deprivation experiments

- Psychogenic dwarfism

- Street child

References and notes

- ^ http://www.feralchildren.com/en/index.php

- ^ "The Green Children of Woolpit". FeralChildren.com. Retrieved 2008-03-21. (About 117 known cases are listed.)

- ^ Bruno Bettelheim, "Feral Children and Autistic Children", The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 64, No. 5. (Mar., 1959), pp. 455-467.

- ^ "Les aveux de Misha Defonseca".

- ^ By Alexander F. Chamber. "The Child and Childhood in Folk-Thought". BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2007. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ Deal, Bama Lutes (2005-04-01). "Chapter 2: Feral Children and Wranitzky's Pantomime-Ballet Das Waldmädchen (1796)" (PDF). The Origin and Performance History of Carl Maria von Weber's Das Waldmädchen (1800). Florida State University. pp. page 16. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Brian Haughton. "The Unsolved Mystery of Kaspar Hauser - Wild Child of Europe". Mysterious People. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ "Naked man deepens mystery of jungle girl". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2007-01-22. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "The Syrian Gazelle Boy". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "The Saharan Gazelle Boy". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "Genie, a modern-day Wild Child". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "Robert, a monkey boy from Uganda". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "Baby Hospital, the Monkey Girl from Sierra Leone". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "Saturday Mthiyane (Saturday Mifune)". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ "Cry of an infant savage". Daily Telegraph. 2006-07-17. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "Daniel, Andes Goat Boy". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "John Ssebunya, the Ugandan Monkey Boy". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ "From monkey boy to choir boy". BBC News. 1999-10-06. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "Bello, the Nigerian Chimp Boy". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Ward. "Ivan Mishukov, the Russian Dog Boy". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ "Edik, the Ukrainian Dog Boy". feralchildren.com. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ Jan McGirk (2001-06-20). "Modern-day Mowgli found scavenging with pack of wild dogs". The Independent. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ "Wolf boy is welcomed home by mother after years in the wild". Daily Telegraph. 2002-04-14. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Andrew Osborn (2004-08-04). "Abandoned boy said to have been raised by a dog". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ "'Wild Cambodia jungle-girl' found". BBC News. 2007-01-19. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Jonathan Watts asks whether Rochom P'ngieng really survived alone in the Cambodian jungle for 18 years | World news | The Guardian

- ^ "Boy found in Uzbekistan after eight years of animal existence". Russian News & Information Agency. 2007-03-01. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ "'Werewolf boy' - who snarls and bites - on the run from police after escaping Moscow clinic". Daily Mail. 2007-12-22. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ^ DeGregory, Lane (2008-08-04). "The Girl in the Window". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ DeGregory, Lane. "The Girl in the Window". Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ DeGregory, Lane (2008-08-10). "The Girl in the Window: Authorities Had Discovered the Rarest and Most Pitiable of Creatures: A Feral Child". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

Bibliography

- Kenneth B. Kidd (2004).Elijah Worrell Making American Boys: Boyology and the Feral Tale. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-4295-8.

- Michael Newton (2002). Savage Boys and Wild Girls: A History of Feral Children. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-21460-6.

- For the first opportune critical approach based on archives : Serge Aroles, L'Enigme des enfants-loups (The Enigma of wolf-children), 2007. ISBN 2748339096.

- Gale Encyclopedia of Psychology, 2nd ed. Gale Group, 2001.

- The Myth of Irrationality - the science of the mind from Plato to Star Trek, by John McCrone, Macmillan London, 1993 (ISBN 0-333-57284-X); Carroll & Graf, New York, 1994 (ISBN 0-7867-0067-X).

External links

- Lost girl recognized by father after 19 years living wild in the jungle

- Children rescued & raised by dogs

- "NOVA Online Transcripts 'Secret of the Wild Child'"

- FeralChildren.com, a comprehensive feral children website

- Feral Children at Curlie

- Chilean boy found raised by dogs, 2001

- Collection of articles on feral children

- Cry of an infant savage - Article about Oxana Malaya