Five Good Emperors

The Five Good Emperors is a term that refers to five consecutive emperors of the Roman Empire who represented a line of virtuous and just rule — Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius. Their reigns lasted between AD 96 to 180. The term was coined by the political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli in 1503:

- From the study of this history we may also learn how a good government is to be established; for while all the emperors who succeeded to the throne by birth, except Titus, were bad, all were good who succeeded by adoption; as in the case of the five from Nerva to Marcus. But so soon as the empire fell once more to the heirs by birth, its ruin recommenced.[1]

Machiavelli claimed that these adopted emperors, through good rule, earned the respect of those around them:

- Titus, Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus, and Marcus had no need of praetorian cohorts, or of countless legions to guard them, but were defended by their own good lives, the good-will of their subjects, and the attachment of the senate.[1]

The rule of these five emperors was also analyzed by 18th-century historian Edward Gibbon in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. According to Gibbon, their rule was a time when "the Roman Empire was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of wisdom and virtue".[2] Gibbon believed these benevolent dictators and their moderate policies were unusual and contrast their more tyrannical and oppressive successors (their predecessors are not covered by Gibbon).

As noted by Machiavelli, the period of the five good emperors was particularly notable for the peaceful method of succession. Each emperor but the last chose his successor by adopting a hand-picked heir, which established a bond legally as strong as that of kinship and thus technically respected the customary—not constitutional—dynastic principle, thus preventing the political turmoil associated with the succession both before and after this period.[3] The naming by Marcus Aurelius of his son Commodus as heir proved to be an unfortunate choice, and is considered by some historians (notably Gibbon) to mark the start of the Empire's decline.[4]

From Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

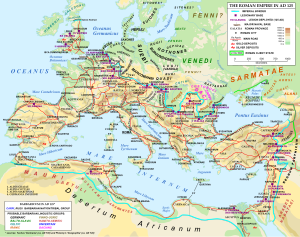

If a man were called to fix the period in the history of the world during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous, he would, without hesitation, name that which elapsed from the death of Domitian to the accession of Commodus. The vast extent of the Roman Empire was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of virtue and wisdom. The armies were restrained by the firm but gentle hand of four successive emperors, whose characters and authority commanded respect. The forms of the civil administration were carefully preserved by Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian and the Antonines, who delighted in the image of liberty, and were pleased with considering themselves as the accountable ministers of the laws. Such princes deserved the honour of restoring the republic had the Romans of their days been capable of enjoying a rational freedom.

More recent historians, while agreeing with many of the details of this analysis, would not entirely agree with Machiavelli and Gibbon's praise of this period. There were more people under the rule of these emperors than the few affluent individuals whose lives are mentioned or recorded in the historical record. A large fraction of the rest were farmers or their dependents, who lived their lives always at the whim of avaricious government officials, or unrestrained bandits, no less during the reign of these "Good Emperors" than before or after. The extent to which these people suffered or were happy continues to be a subject of historical debate.

Additionally, Machiavelli's theory that adoption, rather than birth, led to moderate rule is also questionable. A number of Roman Emperors that Machiavelli did not feel were good rulers were adopted including Augustus, Tiberius and Caligula, though these were all adopted in their capacity as close relatives to the ruler.

Timeline

Nerva–Antonine family tree

| |

| Notes:

Except where otherwise noted, the notes below indicate that an individual's parentage is as shown in the above family tree.

| |

References:

|

References

- ^ a b Machiavelli, Discourses on the First Decade of Titus Livy, Book I, Chapter 10

- ^ Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, I.78

- ^ "Adoptive Succession". Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ "Decline of the Roman Empire". Retrieved 2007-09-18.