Myth of the Noble savage

The term "noble savage" expresses a concept of the universal essential humanity as unencumbered by civilization; the normal essence of an unfettered human.

In the eighteenth-century cult of "Primitivism" the noble savage, uncorrupted by the influences of civilization, was considered more worthy, more authentically noble than the contemporary product of civilized training. Although the phrase noble savage first appeared in Dryden's The Conquest of Granada (1672), the idealized picture of "nature's gentleman" was an aspect of eighteenth-century sentimentalism, among other forces at work.

Since the concept embodies the idea that without the bounds of civilization, humans are essentially good, the basis for the idea of the "noble savage" lies in the doctrine of the goodness of humans, expounded in the first decade of the century by Shaftesbury, who urged a would-be author “to search for that simplicity of manners, and innocence of behaviour, which has been often known among mere savages; ere they were corrupted by our commerce” (Advice to an Author, Part III.iii). His counter to the doctrine of original sin, born amid the optimistic atmosphere of Renaissance humanism, was taken up by his contemporary, the essayist Richard Steele, who attributed the corruption of contemporary manners to false education.

Pre-history of the Noble Savage

During the seventeenth century, as an aspect of Romantic "Primitivism", the figure of the "Good Savage" was held up as a reproach to European civilization, then in the throes of savage wars of religion. People were especially horrified by the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew (1572), in which some 20,000 men, women, and children were massacred, chiefly in Paris, but also throughout France, in a three-day period. This led Montaigne to write his famous essay "Of Cannibals" (1587),[1] in which he stated that although cannibals ceremoniously eat each other, Europeans behave even more barbarously and burn each other alive for disagreeing about religion.

The treatment of indigenous peoples by the Spanish Conquistadors also produced a great deal of bad conscience and recriminations.[2]. Bartolomé de las Casas, who witnessed it, may have been the first to idealize the simple life of the indigenous Americans. He and other observers praised the simple manners of the indigenous Americans and reported that they were incapable of lying.

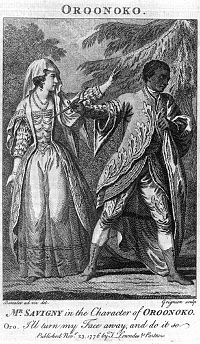

European guilt over colonialism, with its use of recently invented guns on people who didn't have them inspired fictional treatments such as Aphra Behn's novel Oroonoko, or the Royal Slave, about a slave revolt in Surinam in the West Indies. Behn's story was not primarily a protest against slavery but was written for money; and it met readers' expectations by following the conventions of the European romance novella. The leader of the revolt, Oroonoko, is truly noble in that he is a hereditary African prince, and he laments his lost African homeland in the traditional terms of a Golden Age. He is not a savage but dresses and behaves like a European aristocrat. Behn's story was adapted for the stage by Irish playwright Thomas Southerne, who stressed its sentimental aspects, and as time went on it came to be seen as addressing the issues of slavery and colonialism, remaining very popular throughout the Eighteenth Century.

Origin of term "Noble Savage"

In English, the phrase Noble Savage first appeared in Dryden's play, The Conquest of Granada (1672): "I am as free as nature first made man, / Ere the base laws of servitude began, / When wild in woods the noble savage ran." However, the term "Noble Savage" only began to be widely used in the last half of the nineteenth century and then as a term of disparagement. In French the term had been the "Good Savage" (or good "Wild man"), and, in French (and even in eighteenth-century English), the word "savage" did not necessarily have the connotations of cruelty we now associate with it, but meant "wild" as in a wild flower.[3]

The idealized picture of "Nature's Gentleman" was an aspect of eighteenth-century sentimentalism, along with other stock figures such as, the Virtuous Milkmaid, the Servant-More-Clever-than-the-Master (such as Sancho Panza and Figaro, among countless others), and the general theme of virtue in the lowly born. Nature's Gentleman, whether European-born or exotic, takes his place among these tropes, along with the Wise Egyptian, Persian, and Chinaman. He had always existed, from the time of the epic of Gilgamesh, where he appears as Enkiddu, the wild-but-good man who lives with animals; and the untutored-but-noble medieval knight, Parsifal. Even the Biblical David the shepherd boy, falls into this category. Indeed, that virtue and lowly birth can coexist is a time-honored tenet of Abrahamic religion, most conspicuously so in the case of the Founder of the Christian religion. Likewise, the idea that withdrawal from society -- and specifically from cities -- is associated with virtue, is originally a religious one.

Hayy ibn Yaqdhan an Islamic philosophical tale (or thought experiment) by Ibn Tufail from twelfth-century Andalusia, straddles the divide between the religious and the secular. The tale is of interest because it was known to the New England Puritan divine, Cotton Mather. Translated in to English (from Latin) in 1686 and 1708, it tells the story of Hayy, a wild child, raised by a gazelle, without human contact, on a deserted island in the Indian Ocean. Purely through the use of his reason, Hayy goes through all the gradations of knowledge before emerging into human society, where he revealed to be a believer of Natural religion, which Cotton Mather, as a Christian Divine, identified with Primitive Christianity.[4] The figure of Hayy is both a Natural man and a Wise Persian, but not a Noble Savage.

The locus classicus of the eighteenth century portrayal of the American Indian is that of Alexander Pope, unquestionably the most famous and widely-translated poet of his day. In his philosophical poem, "Essay on Man" (1734), Pope wrote:

Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor'd mind /

Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind; / His soul proud Science never taught to stray / Far as the solar walk or milky way; / Yet simple Nature to his hope has giv'n, / Behind the cloud-topp'd hill, a humbler heav'n; / Some safer world in depth of woods embrac'd, / Some happier island in the wat'ry waste, / Where slaves once more their native land behold, / No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold! / To be, contents his natural desire; / He asks no angel's wing, no seraph's fire: / But thinks, admitted to that equal sky, /

His faithful dog shall bear him company.

Pope's poem expresses the typical Age of Reason belief that men are everywhere and in all times the same, which was also Christian doctrine (Pope was a Catholic). He portrays his Indian as a victim ("the poor Indian"), who, although less learned and with less aspirations than his European counterpart, is as good or better and hence equally worthy of salvation. He is a "bon sauvage", but not a noble one.

Attributes of Romantic Primitivism

- Living in harmony with Nature

- Generosity and selflessness

- Innocence

- Inability to lie, fidelity

- Physical health

- Disdain of luxury

- Moral courage

- "Natural" intelligence or innate, untutored wisdom

In the first century AD, all of these qualities had been attributed by Tacitus to the German barbarians in his Germania, in which he contrasted them repeatedly with the softened, Romanized, corrupted Gauls, by inference criticizing his own Roman culture for getting away from its roots -- which was the perennial function of such comparisons. The Germans did not inhabit a "Golden Age" of ease, but were tough and inured to hardship, qualities which Tacitus saw as preferable to the "softness" of civilized life. In antiquity this form of "hard Primitivism", whether viewed as desirable or seen as something to escape, co-existed in rhetorical opposition to the "soft Primitivism" of visions of a lost Golden Age of ease and plenty.

The legendary toughness and martial valor of the Spartans were also admired throughout the ages by hard Primitivists; and in the Eighteenth Century a Scottish writer described Highland countrymen this way:

They greatly excel the Lowlanders in all the exercises that require agility; they are incredibly abstemious, and patient of hunger and fatigue; so steeled against the weather, that in traveling, even when the ground is covered with snow, they never look for a house, or any other shelter but their plaid, in which they wrap themselves up, and go to sleep under the cope of heaven. Such people, in quality of soldiers, must be invincible . . .[5]

The Reaction to Hobbes

Debates about "soft" and "hard" Primitivism intensified with the publication in 1651 of Hobbes's Leviathan (or Commonwealth), a justification of absolute monarchy. Hobbes, a "hard Primitivist", flatly asserted that life in a State of Nature was "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short"-- a "war of all against all". Reacting to the wars of religion of his own time and the previous century, he maintained that the absolute rule of a king was the only possible alternative to the otherwise inevitable violence and anarchy of civil war. Hobbes' hard Primitivism may have been as venerable as the tradition of soft Primitivism, but his use of it was new. He used it to argue that the state was founded on a Social Contract in which men voluntarily gave up their liberty in return for the peace and security provided by total surrender to an absolute ruler, whose legitimacy stemmed from the Social Contract and not from God.

Hobbes' vision of the natural depravity of man inspired fervent disagreement among those who opposed absolute government. His most influential and effective opponent in the last decade of the seventeenth century was Shaftesbury. Shaftesbury countered that, contrary to Hobbes, humans in a State of Nature were neither good nor bad, but that they possessed the emotion of sympathy, and that this emotion was the source and foundation of human goodness and benevolence. Like his contemporaries (all of whom who were educated by reading classical authors such as Livy, Cicero, and Horace), Shaftesbury admired the simplicity of life of classical antiquity. He urged a would-be author “to search for that simplicity of manners, and innocence of behavior, which has been often known among mere savages; ere they were corrupted by our commerce” (Advice to an Author, Part III.iii). Shaftesbury's denial of the innate depravity of man was taken up by contemporaries, such as the popular Irish essayist Richard Steele (1672-1729), who attributed the corruption of contemporary manners to false education. Influenced by Shaftebury and his followers, Eighteenth-Century readers, particularly British ones, were swept up the cult of Sensibility that grew up around his concepts of sympathy and benevolence.

Meanwhile, in France, where those who criticized government or Church authority could be imprisoned without trial or hope of appeal, Primitivism began to be used as a way to protest the repressive rule of Louis XIV and XV, while avoiding censorship. Thus, in the beginning of the Eighteenth century, a French travel writer, the Baron de Lahontan, who had actually lived among the Huron Indians, put potentially dangerously radical Deist and egalitarian arguments in the mouth of a Canadian Indian, Adario, who was perhaps the first figure of the "good" (or "Noble") savage, as we understand it now, to make his appearance on the historical stage:

Adario sings the praises of Natural Religion. . . As against society he puts forward a sort of primitive Communism, of which the certain fruits are Justice and a happy life. . . . He looks with compassion on poor civilized man -- no courage, no strength, incapable of providing himself with food and shelter: a degenerate, a moral cretin, a figure of fun in his blue coat, his red hose, his black hat, his white plume and his green ribands. He never really lives because he is always torturing the life out of himself to clutch at wealth and honors which, even if he wins them, will prove to be but glittering illusions. . . . For science and the arts are but the parents of corruption. The Savage obeys the will of Nature, his kindly mother, therefore he is happy. It is civilized folk who are the real barbarians.[6]

Published in Holland, Lahonton's writings, with their controversial attacks on established religion and social customs, were immensely popular. Over twenty editions were issued between 1703 and 1741, including editions in French, English, Dutch and German. In the later Eighteenth century, the published voyages of Captain James Cook and Louis Antoine de Bougainville seemed to open a glimpse into an unspoiled Edenic culture that still existed in the un-Christianized South Seas. Their popularity inspired Diderot's Supplement to the Voyages of Bougainville (1772), a scathing critique of European sexual hypocrisy and colonial exploitation.

By the end of the century, Benjamin Franklin was poking fun the fashionable craze for sentimentalized primitives in his Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America (1784), but the issue of colonialism did not go away, and the device continued to be used to inspire compassion and to make philosophical and political points.

Two polemical French novels that heralded the start of Romanticism in literature while promoting revolutionary liberal ideals along with new rebirth of religion enthusiasm were Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre's Paul et Virginie (1787), which takes place in Mauritius and criticizes slavery, and Chateaubriand's Atala (1807), in which saintly Nachez Indians of Mississippi are depicted as practicing a purified version of Christianity.

Erroneous Identification of Rousseau with the "Noble Savage"

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, like Shaftesbury, also insisted that man was born good, or rather, with the potential for goodness, and he, too, argued that civilization, with its envy and self-consciousness has made men bad. However Rousseau never used the term "Noble Savage" and was not a Primitivist.

The notion that Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality was essentially a glorification of the State of Nature, and that its influence tended to wholly or chiefly to promote "Primitivism" is one of the most persistent historical errors. –A. O. Lovejoy, “The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality, ” Modern Philology, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Nov., 1923):165-186[7]

Rousseau argued that in a State of Nature men are essentially animals and only by acting together in civil society and binding themselves to its laws, do they become men. For Rousseau only a properly constituted society and reformed system of education could make men good. His fellow philosophe, Voltaire, who did not believe in equality, accused Rousseau of wanting to make people go back and walk on all fours.[8]

Because Jean-Jacques Rousseau was the preferred philosopher of the radical Jacobins of the French Revolution, it was Rousseau above all who became tarred with the accusation of promoting the notion of the "Noble Savage", especially during the polemics about Imperialism and scientific racism in the last half of the nineteenth century.[9]

What most upset traditionalists and defenders of social hierarchy was Rousseau's "romantic" belief in equality. In 1860, shortly after the Sepoy Rebellion in India, two British white supremacists, John Crawfurd and James Hunt mounted a defense of British imperialism based on “scientific racism".[10] Crawfurd, in alliance with Hunt, took over the presidency of the British Anthropological Society, which had been founded with the mission to defend indigenous peoples against slavery and colonial exploitation. Invoking "science" and "realism", the two men derided their "philanthropic" predecessors for believing in human equality and for not recognizing the that mankind was divided into superior and inferior races. Crawfurd, who opposed Darwinian evolution, "denied any unity to mankind, insisting on immutable, hereditary, and timeless differences in racial character, principal amongst which was the 'very great' difference in 'intellectual capacity.'" For Crawfurd, the races had been created separately and were different species. Since Crawfurd was Scots, he thought the Scots "race" superior and all others inferior; whilst Hunt, on the other hand, believed in the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon "race". Crawfurd and Hunt routinely accused those who disagreed with them of believing in "Rousseau’s Noble Savage". (The pair ultimately quarreled because Hunt believed in slavery and Crawfurd did not). "As Ter Ellinson demonstrates, Crawfurd was responsible for re-introducing the Pre-Rousseauian concept of 'the Noble Savage' to modern anthropology, attributing it wrongly and quite deliberately to Rousseau.”[11]

"If Rousseau was not the inventor of the Noble Savage, who was?" writes Ellingson,

One who turns for help to [Hoxie Neale] Fairchild's 1928 study[12], a compendium of citations from romantic writings on the "savage" may be surprised to find [his book] The Noble Savage almost completely lacking in references to its nominal subject. That is, although Fairchild assembles hundreds of quotations from ethnographers, philosophers, novelists, poets, and playwrights from the Seventeenth Century to the Nineteenth Century, showing a rich variety of ways in which writers romanticized and idealized those who Europeans considered "savages", almost none of them explicitly refer to something called the "Noble Savage". Although the words, always duly capitalized, appear on nearly every page, it turns out that in every instance, with four possible exceptions, they are Fairchild's words and not those of the authors cited.[13]

Ellingson finds that any remotely positive portrayal of an indigenous (or working class) person is apt to be characterized (out of context) as a supposedly "unrealistic" or "romanticized" "Noble Savage". He points out that Fairchild includes as an example of a supposed "Noble Savage", a picture of a Negro slave on his knees, lamenting lost his freedom. According to Ellingson, Fairchild ends his book with a denunciation of the (always un-named) believers in Primitivism or "The Noble Savage" -- whom he feels are threatening to unleash the dark forces of irrationality on civilization.[14].

Ellingson argues that the term "Noble Savage", an oxymoron, is a derogatory one, which those who oppose "soft" or romantic primitivism use to discredit (and intimidate) their supposed opponents, whose romantic beliefs they feel are somehow threatening to civilization. Ellingson maintains that virtually none of those accused of believing in the "Noble Savage" ever actually did so. He likens the practice of accusing anthropologists (and other writers and artists) of belief in the Noble Savage to a secularized version of the Inquisition, and he maintains that modern anthropologists have internalized these accusations to the point where they feel they have to ritualistically disavow any belief in "Noble Savage" if they wish to attain credibility in their fields. He says that text books with a painting of a handsome Native American (such as the one one by Benjamin West on this page) are even given to school children with the cautionary caption, "A painting of a Noble Savage".

Hard Primitivism

The most famous modern example of hard primitivism in books and movies was William Golding's Lord of the Flies, published in 1954. The title is said to be a reference to the Biblical devil, Beelzebub. This book, in which a group of school boys shipwrecked on a desert island and "revert" to savage behavior, was a staple of high school and college required reading lists during the Cold War.

In the 1960s, film director Stanley Kubrick, although a political liberal, professed his belief in hard Primitivisism:

Man isn't a noble savage, he's an ignoble savage. He is irrational, brutal, weak, silly, unable to be objective about anything where his own interests are involved — that about sums it up. I'm interested in the brutal and violent nature of man because it's a true picture of him. And any attempt to create social institutions on a false view of the nature of man is probably doomed to failure.

The opening scene of Kubrik's movie 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) depicted prehistoric ape-like men wielding weapons of war, as the tools that supposedly lifted them out of their animal state and made them human. No females were depicted.

A self-styled "hard Primitivist" (i.e., a follower of Thomas Hobbes) is the Australian anthropologist Roger Sandall, who has made a career of exposing other anthropologists whom he considers soft Primitivists and accusing them of exalting the "Noble Savage".[15] Another hard Primitivist is archeologist Lawrence H. Keeley, whose stated mission is to debunk the supposedly widespread myth that "civilized humans have fallen from grace from a simple primeval happiness, a peaceful golden age", by uncovering archeological evidence demonstrating that that violence prevailed in the earliest human societies. Keeley believes that the "noble savage" paradigm has warped anthropological literature to (presumably liberal or leftist) political ends.[16]

Casting their net rather indiscriminately, "hard" Primitivists have disparaged books, genres, and protagonists and (more often) their sidekicks, as "savage" characters too nobly depicted. Examples include Friday from Robinson Crusoe (1719) by Daniel Defoe; Dirk Peters from Edgar Allan Poe's The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838); everyone and everything appearing in Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass poems; Chingachgook and Uncas from James Fenimore Cooper's Leatherstocking Tales (1823 and later); Queequeg from Herman Melville's Moby-Dick (1851); Umslpoagaas from H. Rider Haggard's Allan Quatermain (1885); and Winnetou from Karl May´s Winnetou novels (1893 and later); and Tonto from the Lone Ranger. These criticisms often display the fallacy of Presentism (judging works of the past by the standards of today).

Other twentieth century fictional characters who display Romantic Naturalism and are stigmatized as "Noble Savages" also include figures such as "Mowgli", "Tarzan" and "Conan the Barbarian." Political Correctness has caused the term "Barbarian" to lose its negative connotation and become sympathetically colored. As sensitivity to racist stereotypes has increased, science fiction has often cast space aliens in the role of the "good Other"

In 1906 the Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev wrote a memoir Dersu Uzala, based on the life of a Siberian Nanai hunter who had saved the lives of Arsenyev and his companions on multiple occasions in the wilderness of Manchuria, but was subsequently unable to adjust to life in the city. Although substantially true, this book has been disparaged as a romanticized portrayal of a "noble savage", because Uzala's heroism was apparently not credible to the reviewer.[17].

In fact, any indigenous or non-European character who shows positive qualities or is either handsome, intelligent, or resourceful is subject to being called a "Noble Savage" by detractors. Political correctness is altering the terminology, however. In 1964, the Australian writer Mary Durack published a fictionalized account of Yagan, an Indigenous Australian warrior who played a key part in early resistance to British settlement around Perth, Western Australia, in her children's novel The Courteous Savage: Yagan of the Swan River. When reissued in 1976, it was renamed Yagan of the Bibbulmun because the word "Savage" is now considered negative or even racist. Ter Ellingson also recommends that the term be dropped.

See also

- Anarcho-primitivism

- Neo-Tribalism

- Cultural appropriation

- New Age

- Feral child

- Post modernism

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Xenocentrism

Cultural examples:

References

- ^ Essay "Of Cannibals"

- ^ Anthony Pagden, The Fall of the Natural Man: the American Indian and the origins of comparative ethnology. Cambridge Iberian and Latin American Studies.(Cambridge University Press, 1982)

- ^ "In French, sauvage does not necessarily connote either fierceness or moral degradation; it may simply mean 'wild', as in fleurs sauvages, 'wildflowers'. The term once carried this kinder and gentler connotation in English as well. Dryden who picked up and used Lescarbot's term "noble savage" also wrote in 1697, 'Thus the savage cherry grows. . .' (OED 'Savage', A,I,3); and Shelley. . . wrote in 1820 in his 'Ode to Liberty', 'The vine, the corn, the olive mild / Grew savage yet, to human use unreconciled' (OED 'Savage' A, I, 3)", Ter Elllingson, The Myth of the Noble Savage (University of California, 2001) p. 377. Ellingson believes that Dryden picked up the phrase from a 1609 travelogue about Canada by the French explorer Marc Lescarbot, in which there was a chapter heading: "The Savages are Truly Noble," meaning that they enjoyed the right to hunt game, a privilege in France granted only to hereditary aristocrats. The hero who speaks these words in Dryden's The Conquest of Granada, is a Spanish Muslim, who, at the end of the play, is revealed to be the son of a Christian prince.

- ^ See Doyle R. Quiggle, “Ibn Tufayl's Hayy Ibn Yaqdan in New England: A Spanish-Islamic Tale in Cotton Mather's Christian Philosopher?” Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory, 64: 2, (Summer 2008): 1-32.

- ^ Tobias Smollett, The Adventures of Humphrey Clinker, ([1771] London: Penguin Books, 1967), p. 292.

- ^ See Paul Hazard, The European Mind (1680-1715) (Cleveland, Ohio: Meridian Books [1937], [1969]): 13-14, and passim.

- ^ This article reprinted in “The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality, ” Modern Philology Vol. 21, No. 2 (Nov., 1923):165-186. Reprinted in Essays in the History of Ideas. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1948, 1955, and 1960, is also available on | Jstor

- ^ "It is notorious that Voltaire objected to the education of laborers' children" – Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: The Science of Freedom (New York: W.W. Norton, [1969] 1977), p.36.

- ^ See Ter Ellingson, The Myth of the Noble Savage (University of California Press, 2001).

- ^ see Ter Ellingson, The Myth of the Noble Savage, 2001.

- ^ "John Crawfurd — 'two separate races'". Epress.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- ^ Hoxie Neale Fairchild, The Noble Savage: A Study in Romantic Naturalism (New York, 1928).

- ^ Ellingson, 2001, p. 4.

- ^ Ellingson, p. 380.

- ^ For an appraisal of Roger Sandall see http://home.vicnet.net.au/~abr/Sept01/patrickwolfe.html

- ^ Lawrence H. Keeley, War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage (Oxford, University Press, 1996), p. 5.

- ^ In for example the review from Publishers Weekly posted on Amazon. The book has been made into two movie pictures, the 1961 Soviet film Dersu Uzala by Agasi Babayan (Агаси Бабаян), as well as the 1975 Soviet-Japanese film Dersu Uzala by Akira Kurosawa (黒澤 明)

Further reading

- Barzun, Jacques (2000). From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, 1500 to the Present. New York: Harper Collins. Pp. 282-294, and passim.

- Berkhofer, Robert F. "The White Man's Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present"

- Boas, George ([1933] 1966). The Happy Beast in French Thought in the Seventeenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted by Octagon Press in 1966.

- Boas, George ([1948] 1997). Primitivism and Related Ideas in the Middle Ages. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. "Killing the White Man's Indian: Reinventing Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century"

- Deloria, Vine, Jr. "The Pretend Indian: Images of Native Americans in the Movies"

- Edgerton, Robert (1992). Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0029089255

- Edwards, Brendan Frederick R. (2008) "'He Scarcely Resembles the Real Man': images of the Indian in popular culture" Our Legacy [1]

- Ellingson, Ter. (2001). The Myth of the Noble Savage (Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press).

- Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object

- Fairchild, Hoxie Neale (1928). The Noble Savage: A Study in Romantic Naturalism (New York)

- Fitzgerald, Margaret Mary ([1947] 1976). First Follow Nature: Primitivism in English Poetry 1725-1750. New York: Kings Crown Press. Reprinted New York: Octagon Press.

- Fryd, Vivien Green. "Rereading the Indian in Benjamin West's 'Death of General Wolfe.'" American Art, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Spring, 1995), pp. 72-85. [2]

- Hazard, Paul([1937]1947). The European Mind (1690-1715). Cleveland, Ohio: Meridian Books.

- Keeley, Lawrence H. War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage. Oxford: University Press, 1996.

- Krech, Shepard (2000). The Ecological Indian: Myth and History. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0393321005

- LeBlanc, Steven (2003). Constant battles: the myth of the peaceful, noble savage. New York : St Martin's Press ISBN 0312310897

- Lovejoy, Arthur O. (1923, 1943). “The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality, ” Modern Philology Vol. 21, No. 2 (Nov., 1923):165-186. Reprinted in Essays in the History of Ideas. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1948 and 1960.

- A. O. Lovejoy and George Boas ([1935] 1965. Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted by Octagon Books, 1965. ISBN 0374951306

- Lovejoy, Arthur O. and George Boas. (1935). A Documentary History of Primitivism and Related Ideas, vol. 1. Baltimore.

- Olupọna, Jacob Obafẹmi Kẹhinde, Editor. (2003) Beyond primitivism: indigenous religious traditions and modernity. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 0415273196, 9780415273190

- Pagden, Anthony (1982). The Fall of the Natural Man: The American Indian and the origins of comparative ethnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pinker, Steven (2002). The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Viking ISBN 0-670-03151-8

- Sandall, Roger (2001). The Culture Cult: Designer Tribalism and Other Essays ISBN 0-8133-3863-8

- Rollins, Peter C. "Hollywood's Indian : the portrayal of the Native American in film"

- Tinker, Chaunchy Brewster (1922). Nature's Simple Plan: a phase of radical thought in the mid-eighteenth century. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Torgovnick, Marianna (1991). Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives (Chicago)

- Whitney, Lois Payne (1934). Primitivism and the Idea of Progress in English Popular Literature of the Eighteenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press

- Eric R. Wolf, 1982. Europe and the People without History'.' Berkeley: University of California Press.