RAID

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2007) |

RAID is an acronym first defined by David A. Patterson, Garth A. Gibson, and Randy Katz at the University of California, Berkeley in 1987 to describe a redundant array of inexpensive disks,[1] a technology that allowed computer users to achieve high levels of storage reliability from low-cost and less reliable PC-class disk-drive components, via the technique of arranging the devices into arrays for redundancy.

Marketers representing industry RAID manufacturers later reinvented the term to describe a redundant array of independent disks as a means of dissociating a "low cost" expectation from RAID technology.[2]

"RAID" is now used as an umbrella term for computer data storage schemes that can divide and replicate data among multiple hard disk drives. The different schemes/architectures are named by the word RAID followed by a number, as in RAID 0, RAID 1, etc. RAID's various designs involve two key design goals: increase data reliability and/or increase input/output performance. When multiple physical disks are set up to use RAID technology, they are said to be in a RAID array[3]. This array distributes data across multiple disks, but the array is seen by the computer user and operating system as one single disk. RAID can be set up to serve several different purposes.

Principles

RAID combines two or more physical hard disks into a single logical unit using special hardware or software. Hardware solutions are often designed to present themselves to the attached system as a single hard drive, so that the operating system would be unaware of the technical workings. For example, if one were to configure a hardware-based RAID-5 volume using three 250GB hard drives (two drives for data, and one for parity), the operating system would be presented with a single 500GB volume. Software solutions are typically implemented in the operating system and would present the RAID volume as a single drive to applications running within the operating system.

There are three key concepts in RAID: mirroring, the writing of identical data to more than one disk; striping, the splitting of data across more than one disk; and error correction, where redundant ("parity") data is stored to allow problems to be detected and possibly fixed (known as fault tolerance). Different RAID schemes use one or more of these techniques, depending on the system requirements. The purpose of using RAID is to improve reliability and availability of data, ensuring that important data is not harmed in case of hardware failure, and/or to increase the speed of file input/output.

Each RAID scheme affects reliability and performance in different ways. Every additional disk included in an array increases the likelihood that one will fail, but by using error checking and/or mirroring, the array as a whole can be made more reliable by the ability to survive and recover from a failure. Basic mirroring can speed up the reading of data, as a system can read different data from multiple disks at the same time, but it may be slow for writing if the configuration requires that all disks must confirm that the data is correctly written. Striping, often used for increasing performance, writes each bit to a different disk, allowing the data to be reconstructed from multiple disks faster than a single disk could send the same data. Error checking typically will slow down performance as data needs to be read from multiple places and then compared. The design of any RAID scheme is often a compromise in one or more respects, and understanding the requirements of a system is important. Modern disk arrays typically provide the facility to select an appropriate RAID configuration.

Redundancy is achieved by either writing the same data to multiple drives (known as mirroring), or collecting parity data across the array, calculated such that the failure of one disk (or possibly more, depending on the RAID scheme) in the array will not result in loss of data. A failed disk may be replaced with a good one to allow the lost data to be reconstructed from the remaining data and the parity data.

Organization

Organizing disks into a redundant array decreases the usable storage capacity. For instance, a 2-disk RAID 1 array loses half of the total capacity that would have otherwise been available using both disks independently, and a RAID 5 array with several disks loses the capacity of one disk. Other types of RAID arrays are arranged, for example, so that they are faster to write to and read from than a single disk.

There are various combinations of these approaches giving different trade-offs of protection against data loss, capacity, and speed. RAID levels 0, 1, and 5 are the most commonly found, and cover most requirements.

- RAID 0 (striped disks) distributes data across multiple disks in a way that gives improved speed at any given instant. If one disk fails, however, all of the data on the array will be lost, as there is neither parity nor mirroring. In this regard, RAID 0 is somewhat of a misnomer, in that RAID 0 is non-redundant. A RAID 0 array requires a minimum of two drives. A RAID 0 configuration can be applied to a single drive provided that the RAID controller is hardware and not software (i.e. OS-based arrays) and allows for such configuration. This allows a single drive to be added to a controller already containing another RAID configuration when the user does not wish to add the additional drive to the existing array. In this case, the controller would be set up as RAID only (as opposed to SCSI only (no RAID)), which requires that each individual drive be a part of some sort of RAID array.

- RAID 1 mirrors the contents of the disks, making a form of 1:1 ratio realtime backup. The contents of each disk in the array are identical to that of every other disk in the array. A RAID 1 array requires a minimum of two drives. RAID 1 mirrors, though during the writing process copy the data identically to both drives, would not be suitable as a permanent backup solution, as RAID technology by design allows for certain failures to take place.

- RAID 3 or 4 (striped disks with dedicated parity) combines three or more disks in a way that protects data against loss of any one disk. Fault tolerance is achieved by adding an extra disk to the array and dedicating it to storing parity information. The storage capacity of the array is reduced by one disk. A RAID 3 or 4 array requires a minimum of three drives: two to hold striped data, and a third drive to hold parity data.

- RAID 5 (striped disks with distributed parity) combines three or more disks in a way that protects data against the loss of any one disk. It is similar to RAID 3 but the parity is not stored on one dedicated drive, instead parity information is interspersed across the drive array. The storage capacity of the array is a function of the number of drives minus the space needed to store parity. The maximum number of drives that can fail in any RAID 5 configuration without losing data is only one. Losing two drives in a RAID 5 array is referred to as a "double fault" and results in data loss.

- RAID 6 (striped disks with dual parity) combines four or more disks in a way that protects data against loss of any two disks.

- RAID 1+0 (or 10) is a mirrored data set (RAID 1) which is then striped (RAID 0), hence the "1+0" name. A RAID 10 array requires a minimum of two drives, but is more commonly implemented with 4 drives to take advantage of speed benefits.

- RAID 0+1 (or 01) is a striped data set (RAID 0) which is then mirrored (RAID 1). A RAID 0+1 array requires a minimum of four drives: two to hold the striped data, plus another two to mirror the first pair.

RAID can involve significant computation when reading and writing information. With traditional "real" RAID hardware, a separate controller does this computation. In other cases the operating system or simpler and less expensive controllers require the host computer's processor to do the computing, which reduces the computer's performance on processor-intensive tasks (see Operating system based ("software RAID") and Firmware/driver-based RAID below). Simpler RAID controllers may provide only levels 0 and 1, which require less processing.

RAID systems with redundancy continue working without interruption when one (or possibly more, depending on the type of RAID) disks of the array fail, although they are then vulnerable to further failures. When the bad disk is replaced by a new one the array is rebuilt while the system continues to operate normally. Some systems have to be powered down when removing or adding a drive; others support hot swapping, allowing drives to be replaced without powering down. RAID with hot-swapping is often used in high availability systems, where it is important that the system remains running as much of the time as possible.

Note that a RAID controller itself can become the single point of failure within a system.

Standard levels

A number of standard schemes have evolved which are referred to as levels. There were five RAID levels originally conceived, but many more variations have evolved, notably several nested levels and many non-standard levels (mostly proprietary).

Following is a brief summary of the most commonly used RAID levels.[4] Space efficiency is given as amount of storage space available in an array of n disks, in multiples of the capacity of a single drive. For example if an array holds n=5 drives of 250GB and efficiency is n-1 then available space is 4 times 250GB or roughly 1TB.

| Level | Description | Minimum # of disks | Space Efficiency | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAID 0 | "Striped set without parity" or "Striping". Provides improved performance and additional storage but no redundancy or fault tolerance. Because there is no redundancy, this level is not actually a Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks, i.e. not true RAID. However, because of the similarities to RAID (especially the need for a controller to distribute data across multiple disks), simple stripe sets are normally referred to as RAID 0. Any disk failure destroys the array, which has greater consequences with more disks in the array (at a minimum, catastrophic data loss is twice as severe compared to single drives without RAID). A single disk failure destroys the entire array because when data is written to a RAID 0 drive, the data is broken into fragments. The number of fragments is dictated by the number of disks in the array. The fragments are written to their respective disks simultaneously on the same sector. This allows smaller sections of the entire chunk of data to be read off the drive in parallel, increasing bandwidth. RAID 0 does not implement error checking so any error is unrecoverable. More disks in the array means higher bandwidth, but greater risk of data loss. | 2 | n |

|

| RAID 1 | 'Mirrored set without parity' or 'Mirroring'. Provides fault tolerance from disk errors and failure of all but one of the drives. Increased read performance occurs when using a multi-threaded operating system that supports split seeks, as well as a very small performance reduction when writing. Array continues to operate so long as at least one drive is functioning. Using RAID 1 with a separate controller for each disk is sometimes called duplexing. | 2 | 1 (size of the smallest disk) |

|

| RAID 2 | Hamming code parity. Disks are synchronized and striped in very small stripes, often in single bytes/words. Hamming codes error correction is calculated across corresponding bits on disks, and is stored on multiple parity disks. | 3 | ||

| RAID 3 | Striped set with dedicated parity or bit interleaved parity or byte level parity.

This mechanism provides fault tolerance similar to RAID 5. However, because the stripe across the disks is a lot smaller than a filesystem block, reads and writes to the array perform like a single drive with a high linear write performance. For this to work properly, the drives must have synchronised rotation. If one drive fails, the performance doesn't change. |

3 | n-1 |

|

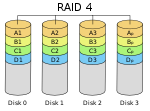

| RAID 4 | Block level parity. Identical to RAID 3, but does block-level striping instead of byte-level striping. In this setup, files can be distributed between multiple disks. Each disk operates independently which allows I/O requests to be performed in parallel, though data transfer speeds can suffer due to the type of parity. The error detection is achieved through dedicated parity and is stored in a separate, single disk unit. | 3 | n-1 |

|

| RAID 5 | Striped set with distributed parity or interleave parity. Distributed parity requires all drives but one to be present to operate; drive failure requires replacement, but the array is not destroyed by a single drive failure. Upon drive failure, any subsequent reads can be calculated from the distributed parity such that the drive failure is masked from the end user. The array will have data loss in the event of a second drive failure and is vulnerable until the data that was on the failed drive is rebuilt onto a replacement drive. A single drive failure in the set will result in reduced performance of the entire set until the failed drive has been replaced and rebuilt. | 3 | n-1 |

|

| RAID 6 | Striped set with dual distributed parity. Provides fault tolerance from two drive failures; array continues to operate with up to two failed drives. This makes larger RAID groups more practical, especially for high availability systems. This becomes increasingly important because large-capacity drives lengthen the time needed to recover from the failure of a single drive. Single parity RAID levels are vulnerable to data loss until the failed drive is rebuilt: the larger the drive, the longer the rebuild will take. Dual parity gives time to rebuild the array without the data being at risk if a (single) additional drive fails before the rebuild is complete. | 4 | n-2 |

|

Nested (hybrid) RAID

In what was originally termed hybrid RAID,[5] many storage controllers allow RAID levels to be nested. The elements of a RAID may be either individual disks or RAIDs themselves. Nesting more than two deep is unusual.

As there is no basic RAID level numbered larger than 9, nested RAIDs are usually unambiguously described by concatenating the numbers indicating the RAID levels, sometimes with a "+" in between. For example, RAID 10 (or RAID 1+0) consists of several level 1 arrays of physical drives, each of which is one of the "drives" of a level 0 array striped over the level 1 arrays. It is not called RAID 01, to avoid confusion with RAID 1, or indeed, RAID 01. When the top array is a RAID 0 (such as in RAID 10 and RAID 50) most vendors omit the "+", though RAID 5+0 is clearer.

- RAID 0+1: striped sets in a mirrored set (minimum four disks; even number of disks) provides fault tolerance and improved performance but increases complexity. The key difference from RAID 1+0 is that RAID 0+1 creates a second striped set to mirror a primary striped set. The array continues to operate with one or more drives failed in the same mirror set, but if drives fail on both sides of the mirror the data on the RAID system is lost.

- RAID 1+0: mirrored sets in a striped set (minimum two disks but more commonly four disks to take advantage of speed benefits; even number of disks) provides fault tolerance and improved performance but increases complexity.

- The key difference from RAID 0+1 is that RAID 1+0 creates a striped set from a series of mirrored drives. In a failed disk situation, RAID 1+0 performs better because all the remaining disks continue to be used. The array can sustain multiple drive losses so long as no mirror loses all its drives.

- RAID 5+1: mirror striped set with distributed parity (some manufacturers label this as RAID 53).

Non-standard levels

Many configurations other than the basic numbered RAID levels are possible, and many companies, organizations, and groups have created their own non-standard configurations, in many cases designed to meet the specialised needs of a small niche group. Most of these non-standard RAID levels are proprietary.

- Storage Computer Corporation used to call a cached version of RAID 3 and 4, RAID 7. Storage Computer Corporation is now defunct.

- EMC Corporation used to offer RAID S as an alternative to RAID 5 on their Symmetrix systems. Their latest generations of Symmetrix, the DMX and the V-Max series, do not support RAID S (instead they support RAID-1, RAID-5 and RAID-6.)

- The ZFS filesystem, available in Solaris, OpenSolaris and FreeBSD, offers RAID-Z, which solves RAID 5's write hole problem.

- Hewlett-Packard's Advanced Data Guarding (ADG) is a form of RAID 6.

- NetApp's Data ONTAP uses RAID-DP (also referred to as "double", "dual", or "diagonal" parity), is a form of RAID 6, but unlike many RAID 6 implementations, does not use distributed parity as in RAID 5. Instead, two unique parity disks with separate parity calculations are used. This is a modification of RAID 4 with an extra parity disk.

- Accusys Triple Parity (RAID TP) implements three independent parities by extending RAID 6 algorithms on its FC-SATA and SCSI-SATA RAID controllers to tolerate three-disk failure.

- Linux MD RAID10 (RAID10) implements a general RAID driver that defaults to a standard RAID 1+0 with four drives, but can have any number of drives. MD RAID10 can run striped and mirrored with only two drives with the f2 layout (mirroring with striped reads, normal Linux software RAID 1 does not stripe reads, but can read in parallel).[6]

- Infrant (now part of Netgear) X-RAID offers dynamic expansion of a RAID5 volume without having to back up or restore the existing content. Just add larger drives one at a time, let it resync, then add the next drive until all drives are installed. The resulting volume capacity is increased without user downtime. (It should be noted that this is also possible in Linux, when utilizing Mdadm utility. It has also been possible in the EMC Clariion and HP MSA arrays for several years.) The new X-RAID2 found on x86 ReadyNas, that is ReadyNas with Intel CPUs, offers dynamic expansion of a RAID-5 or RAID-6 volume (note X-RAID2 Dual Redundancy not available on all X86 ReadyNas) without having to back up or restore the existing content etc. A major advantage over X-RAID, is that using X-RAID2 you do not need to replace all the disks to get extra space, you only need to replace two disks using single redundancy or four disks using dual redundancy to get more redundant space.

- BeyondRAID, created by Data Robotics and used in the Drobo series of products, implements both mirroring and striping simultaneously or individually dependent on disk and data context. It offers expandability without reconfiguration, the ability to mix and match drive sizes and the ability to reorder disks. It supports NTFS, HFS+, FAT32, and EXT3 file systems[7]. It also uses thin provisioning to allow for single volumes up to 16 TB depending on the host operating system support.

- Hewlett-Packard's EVA series arrays implement vRAID - vRAID-0, vRAID-1, vRAID-5, and vRAID-6. The EVA allows drives to be placed in groups (called Disk Groups) that form a pool of data blocks on top of which the RAID level is implemented. Any Disk Group may have "virtual disks" or LUNs of any vRAID type, including mixing vRAID types in the same Disk Group - a unique feature. vRAID levels are more closely aligned to Nested RAID levels - vRAID-1 is actually a RAID 1+0 (or RAID10), vRAID-5 is actually a RAID 5+0 (or RAID50), etc. Also, drives may be added on-the-fly to an existing Disk Group, and the existing virtual disks data is redistributed evenly over all the drives, thereby allowing dynamic performance and capacity growth.

- IBM (Among others) has implemented a RAID 1E (Level 1 Enhanced). With an even number of disks it is similar to a RAID 10 array, but, unlike a RAID 10 array, it can also be implemented with an odd number of drives. In either case, the total available disk space is n/2. It requires a minimum of three drives.

Parity calculation; rebuilding failed drives

Parity data in a RAID environment is calculated using the Boolean XOR function. For example, here is a simple RAID 4 three-disk setup consisting of two drives that hold 8 bits of data each and a third drive that will be used to hold parity data.

Drive 1: 01101101

Drive 2: 11010100

To calculate parity data for the two drives, an XOR is performed on their data.

i.e. 01101101 XOR 11010100 = 10111001

The resulting parity data, 10111001, is then stored on Drive 3, the dedicated parity drive.

Should any of the three drives fail, the contents of the failed drive can be reconstructed on a replacement (or "hot spare") drive by subjecting the data from the remaining drives to the same XOR operation. If Drive 2 were to fail, its data could be rebuilt using the XOR results of the contents of the two remaining drives, Drive 3 and Drive 1:

Drive 3: 10111001

Drive 1: 01101101

i.e. 10111001 XOR 01101101 = 11010100

The result of that XOR calculation yields Drive 2's contents. 11010100 is then stored on Drive 2, fully repairing the array. This same XOR concept applies similarly to larger arrays, using any number of disks. In the case of a RAID 3 array of 12 drives, 11 drives participate in the XOR calculation shown above and yield a value that is then stored on the dedicated parity drive.

RAID is not data backup

RAID is not a good alternative to backing up data. Data may become damaged or destroyed without harm to the drive(s) on which they are stored. For example, some of the data may be overwritten by a system malfunction; a file may be damaged or deleted by user error or malice and not noticed for days or weeks. RAID can also be overwhelmed by catastrophic failure that exceeds its recovery capacity and, of course, the entire array is at risk of physical damage by fire, natural disaster, or human forces.

Implementations

It has been suggested that Vinum volume manager be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since November 2008. |

(Specifically, the section comparing hardware / software raid)

The distribution of data across multiple drives can be managed either by dedicated hardware or by software. When done in software the software may be part of the operating system or it may be part of the firmware and drivers supplied with the card.

Operating system based ("software RAID")

Software implementations are now provided by many operating systems. A software layer sits above the (generally block-based) disk device drivers and provides an abstraction layer between the logical drives (RAIDs) and physical drives. Most common levels are RAID 0 (striping across multiple drives for increased space and performance) and RAID 1 (mirroring two drives), followed by RAID 1+0, RAID 0+1, and RAID 5 (data striping with parity) are supported.

- Apple's Mac OS X Server supports RAID 0, RAID 1 and RAID 1+0.[8]

- FreeBSD supports RAID 0, RAID 1, RAID 3, and RAID 5 and all layerings of the above via GEOM modules[9][10] and ccd.[11], as well as supporting RAID 0, RAID 1, RAID-Z, and RAID-Z2 (similar to RAID-5 and RAID-6 respectively), plus nested combinations of those via ZFS.

- Microsoft's server operating systems support 3 RAID levels; RAID 0, RAID 1, and RAID 5. Some of the Microsoft desktop operating systems support RAID such as Windows XP Professional which supports RAID level 0 in addition to spanning multiple disks but only if using dynamic disks and volumes. Windows XP supports RAID 0, 1, and 5 with a simple file patch [14]. RAID functionality in Windows is slower than hardware RAID, but allows a RAID array to be moved to another machine with no compatibility issues.

- NetBSD supports RAID 0, RAID 1, RAID 4 and RAID 5 (and any nested combination of those like 1+0) via its software implementation, named RAIDframe.

- OpenBSD aims to support RAID 0, RAID 1, RAID 4 and RAID 5 via its software implementation softraid.

- OpenSolaris and Solaris 10 supports RAID 0, RAID 1, RAID 5 (or the similar "RAID Z" found only on ZFS), and RAID 6 (and any nested combination of those like 1+0) via ZFS and now has the ability to boot from a ZFS volume on both x86 and UltraSPARC. Through SVM, Solaris 10 and earlier versions support RAID 1 for the boot filesystem, and adds RAID 0 and RAID 5 support (and various nested combinations) for data drives.

Software RAID has advantages and disadvantages compared to hardware RAID. The software must run on a host server attached to storage, and server's processor must dedicate processing time to run the RAID software. This is negligible for RAID 0 and RAID 1, but may become significant when using parity-based arrays and either accessing several arrays at the same time or running many disks. Furthermore all the busses between the processor and the disk controller must carry the extra data required by RAID which may cause congestion.

Another concern with operating system-based RAID is the boot process. It can be difficult or impossible to set up the boot process such that it can fail over to another drive if the usual boot drive fails. Such systems can require manual intervention to make the machine bootable again after a failure. There are exceptions to this, such as the LILO bootloader for Linux, loader for FreeBSD[15] , and some configurations of the GRUB bootloader natively understand RAID-1 and can load a kernel. If the BIOS recognizes a broken first disk and refers bootstrapping to the next disk, such a system will come up without intervention, but the BIOS might or might not do that as intended. A hardware RAID controller typically has explicit programming to decide that a disk is broken and fall through to the next disk.

Hardware RAID controllers can also carry battery-powered cache memory. For data safety in modern systems the user of software RAID might need to turn the write-back cache on the disk off (but some drives have their own battery/capacitors on the write-back cache, a UPS, and/or implement atomicity in various ways, etc). Turning off the write cache has a performance penalty that can, depending on workload and how well supported command queuing in the disk system is, be significant. The battery backed cache on a RAID controller is one solution to have a safe write-back cache.

Finally operating system-based RAID usually uses formats specific to the operating system in question so it cannot generally be used for partitions that are shared between operating systems as part of a multi-boot setup. However, this allows RAID disks to be moved from one computer to a computer with an operating system or file system of the same type, which can be more difficult when using hardware RAID (e.g. #1: When one computer uses a hardware RAID controller from one manufacturer and another computer uses a controller from a different manufacturer, drives typically cannot be interchanged. e.g. #2: If the hardware controller 'dies' before the disks do, data may become unrecoverable unless a hardware controller of the same type is obtained, unlike with firmware-based or software-based RAID).

Most operating system-based implementations allow RAIDs to be created from partitions rather than entire physical drives. For instance, an administrator could divide an odd number of disks into two partitions per disk, mirror partitions across disks and stripe a volume across the mirrored partitions to emulate IBM's RAID 1E configuration. Using partitions in this way also allows mixing reliability levels on the same set of disks. For example, one could have a very robust RAID 1 partition for important files, and a less robust RAID 5 or RAID 0 partition for less important data. (Some BIOS-based controllers offer similar features, e.g. Intel Matrix RAID.) Using two partitions on the same drive in the same RAID is, however, dangerous. (e.g. #1: Having all partitions of a RAID-1 on the same drive will, obviously, make all the data inaccessible if the single drive fails. e.g. #2: In a RAID 5 array composed of four drives 250 + 250 + 250 + 500 GB, with the 500-GB drive split into two 250 GB partitions, a failure of this drive will remove two partitions from the array, causing all of the data held on it to be lost).

Hardware-based

Hardware RAID controllers use different, proprietary disk layouts, so it is not usually possible to span controllers from different manufacturers. They do not require processor resources, the BIOS can boot from them, and tighter integration with the device driver may offer better error handling.

A hardware implementation of RAID requires at least a special-purpose RAID controller. On a desktop system this may be a PCI expansion card, PCI-e expansion card or built into the motherboard. Controllers supporting most types of drive may be used – IDE/ATA, SATA, SCSI, SSA, Fibre Channel, sometimes even a combination. The controller and disks may be in a stand-alone disk enclosure, rather than inside a computer. The enclosure may be directly attached to a computer, or connected via SAN. The controller hardware handles the management of the drives, and performs any parity calculations required by the chosen RAID level.

Most hardware implementations provide a read/write cache, which, depending on the I/O workload, will improve performance. In most systems the write cache is non-volatile (i.e. battery-protected), so pending writes are not lost on a power failure.

Hardware implementations provide guaranteed performance, add no overhead to the local CPU complex and can support many operating systems, as the controller simply presents a logical disk to the operating system.

Hardware implementations also typically support hot swapping, allowing failed drives to be replaced while the system is running.

Firmware/driver-based RAID

Operating system-based RAID doesn't always protect the boot process and is generally impractical on desktop versions of Windows (as described above). Hardware RAID controllers are expensive and proprietary. To fill this gap, cheap "RAID controllers" were introduced that do not contain a RAID controller chip, but simply a standard disk controller chip with special firmware and drivers. During early stage bootup the RAID is implemented by the firmware; when a protected-mode operating system kernel such as Linux or a modern version of Microsoft Windows is loaded the drivers take over.

These controllers are described by their manufacturers as RAID controllers, and it is rarely made clear to purchasers that the burden of RAID processing is borne by the host computer's central processing unit, not the RAID controller itself, thus introducing the aforementioned CPU overhead which hardware controllers don't suffer from. Firmware controllers often can only use certain types of hard drives in their RAID arrays (e.g. SATA for Intel Matrix RAID, as there is neither SCSI nor PATA support in modern Intel ICH southbridges; however, motherboard makers implement RAID controllers outside of the southbridge on some motherboards). Before their introduction, a "RAID controller" implied that the controller did the processing, and the new type has become known in technically knowledgeable circles as "fake RAID" even though the RAID itself is implemented correctly. Adaptec calls them "HostRAID".

Network-attached storage

While not directly associated with RAID, Network-attached storage (NAS) is an enclosure containing disk drives and the equipment necessary to make them available over a computer network, usually Ethernet. The enclosure is basically a dedicated computer in its own right, designed to operate over the network without screen or keyboard. It contains one or more disk drives; multiple drives may be configured as a RAID.

Hot spares

Both hardware and software RAIDs with redundancy may support the use of hot spare drives, a drive physically installed in the array which is inactive until an active drive fails, when the system automatically replaces the failed drive with the spare, rebuilding the array with the spare drive included. This reduces the mean time to recovery (MTTR), though it doesn't eliminate it completely. Subsequent additional failure(s) in the same RAID redundancy group before the array is fully rebuilt can result in loss of the data; rebuilding can take several hours, especially on busy systems.

Rapid replacement of failed drives is important as the drives of an array will all have had the same amount of use, and may tend to fail at about the same time rather than randomly. RAID 6 without a spare uses the same number of drives as RAID 5 with a hot spare and protects data against simultaneous failure of up to two drives, but requires a more advanced RAID controller. Further, a hot spare can be shared by multiple RAID sets.

Reliability terms

- Failure rate

- Failure rate is only meaningful if failure is defined. If a failure is defined as the loss of a single drive (logistical failure rate), the failure rate will be the sum of individual drives' failure rates. In this case the failure rate of the RAID will be larger than the failure rate of its constituent drives. On the other hand, if failure is defined as loss of data (system failure rate), then the failure rate of the RAID will be less than that of the constituent drives. How much less depends on the type of RAID.

- Mean time to data loss (MTTDL)

- In this context, the average time before a loss of data in a given array.[16]. Mean time to data loss of a given RAID may be higher or lower than that of its constituent hard drives, depending upon what type of RAID is employed. The referenced report assumes times to data loss are exponentially distributed. This means 63.2% of all data loss will occur between time 0 and the MTTDL.

- Mean time to recovery (MTTR)

- In arrays that include redundancy for reliability, this is the time following a failure to restore an array to its normal failure-tolerant mode of operation. This includes time to replace a failed disk mechanism as well as time to re-build the array (i.e. to replicate data for redundancy).

- Unrecoverable bit error rate (UBE)

- This is the rate at which a disk drive will be unable to recover data after application of cyclic redundancy check (CRC) codes and multiple retries.

- Write cache reliability

- Some RAID systems use RAM write cache to increase performance. A power failure can result in data loss unless this sort of disk buffer is supplemented with a battery to ensure that the buffer has enough time to write from RAM back to disk.

- Atomic write failure

- Also known by various terms such as torn writes, torn pages, incomplete writes, interrupted writes, non-transactional, etc.

Problems with RAID

The theory behind the error correction in RAID assumes that failures of drives are independent. Given these assumptions it is possible to calculate how often they can fail and to arrange the array to make data loss arbitrarily improbable.

In practice, the drives are often the same ages, with similar wear. Since many drive failures are due to mechanical issues which are more likely on older drives, this violates those assumptions and failures are in fact statistically correlated. In practice then, the chances of a second failure before the first has been recovered is not nearly as unlikely as might be supposed, and data loss can in practice occur at significant rates.[17]

A common misconception is that "server-grade" drives fail less frequently than consumer-grade drives. Two different, independent studies, by Carnegie Mellon University and Google, have shown that failure rates are largely independent of the supposed "grade" of the drive.[18]

Atomicity

This is a little understood and rarely mentioned failure mode for redundant storage systems that do not utilize transactional features. Database researcher Jim Gray wrote "Update in Place is a Poison Apple"[19] during the early days of relational database commercialization. However, this warning largely went unheeded and fell by the wayside upon the advent of RAID, which many software engineers mistook as solving all data storage integrity and reliability problems. Many software programs update a storage object "in-place"; that is, they write a new version of the object on to the same disk addresses as the old version of the object. While the software may also log some delta information elsewhere, it expects the storage to present "atomic write semantics," meaning that the write of the data either occurred in its entirety or did not occur at all.

However, very few storage systems provide support for atomic writes, and even fewer specify their rate of failure in providing this semantic. Note that during the act of writing an object, a RAID storage device will usually be writing all redundant copies of the object in parallel, although overlapped or staggered writes are more common when a single RAID processor is responsible for multiple drives. Hence an error that occurs during the process of writing may leave the redundant copies in different states, and furthermore may leave the copies in neither the old nor the new state. The little known failure mode is that delta logging relies on the original data being either in the old or the new state so as to enable backing out the logical change, yet few storage systems provide an atomic write semantic on a RAID disk.

While the battery-backed write cache may partially solve the problem, it is applicable only to a power failure scenario.

Since transactional support is not universally present in hardware RAID, many operating systems include transactional support to protect against data loss during an interrupted write. Novell Netware, starting with version 3.x, included a transaction tracking system. Microsoft introduced transaction tracking via the journaling feature in NTFS. Ext4 has journaling with checksums; ext3 has journaling without checksums but an "append-only" option, or ext3COW (Copy on Write). If the journal itself in a filesystem is corrupted though, this can be problematic. The journaling in NetApp WAFL file system gives atomicity by never updating the data in place, as does ZFS. An alternative method to journaling is soft updates, which are used in some BSD-derived system's implementation of UFS.

This can present as a sector read failure. Some RAID implementations protect against this failure mode by remapping the bad sector, using the redundant data to retrieve a good copy of the data, and rewriting that good data to the newly mapped replacement sector. The UBE (Unrecoverable Bit Error) rate is typically specified at 1 bit in 1015 for enterprise class disk drives (SCSI, FC, SAS) , and 1 bit in 1014 for desktop class disk drives (IDE/ATA/PATA, SATA). Increasing disk capacities and large RAID 5 redundancy groups have led to an increasing inability to successfully rebuild a RAID group after a disk failure because an unrecoverable sector is found on the remaining drives. Double protection schemes such as RAID 6 are attempting to address this issue, but suffer from a very high write penalty.

Write cache reliability

The disk system can acknowledge the write operation as soon as the data is in the cache, not waiting for the data to be physically written. This typically occurs in old, non-journaled systems such as FAT32, or if the Linux/Unix "writeback" option is chosen without any protections like the "soft updates" option (to promote I/O speed whilst trading-away data reliability). A power outage or system hang such as a BSOD can mean a significant loss of any data queued in such cache.

Often a battery is protecting the write cache, mostly solving the problem. If a write fails because of power failure, the controller may complete the pending writes as soon as restarted. This solution still has potential failure cases: the battery may have worn out, the power may be off for too long, the disks could be moved to another controller, the controller itself could fail. Some disk systems provide the capability of testing the battery periodically, however this leaves the system without a fully charged battery for several hours.

An additional concern about write cache reliability exists, specifically regarding devices equipped with a write-back cache—a caching system which reports the data as written as soon as it is written to cache, as opposed to the non-volatile medium.[20] The safer cache technique is write-through, which reports transactions as written when they are written to the non-volatile medium.

Equipment compatibility

The disk formats on different RAID controllers are not necessarily compatible, so that it may not be possible to read a RAID on different hardware. Consequently a non-disk hardware failure may require using identical hardware, or a data backup, to recover the data. Software RAID however, such as implemented in the Linux kernel, alleviates this concern, as the setup is not hardware dependent, but runs on ordinary disk controllers. Additionally, Software RAID1 disks (and some hardware RAID1 disks, for example Silicon Image 5744) can be read like normal disks, so no RAID system is required to retrieve the data. Data recovery firms typically have a very hard time recovering data from RAID drives, with the exception of RAID1 drives with conventional data structure.

Data recovery in the event of a failed array

With larger disk capacities the odds of a disk failure during rebuild are not negligible. In that event the difficulty of extracting data from a failed array must be considered. Only RAID 1 stores all data on each disk. Although it may depend on the controller, some RAID 1 disks can be read as a single conventional disk. This means a dropped RAID 1 disk, although damaged, can often be reasonably easily recovered using a software recovery program or CHKDSK. If the damage is more severe, data can often be recovered by professional drive specialists. RAID5 and other striped or distributed arrays present much more formidable obstacles to data recovery in the event the array goes down.

Drive error recovery algorithms

Many modern drives have internal error recovery algorithms that can take upwards of a minute to recover and re-map data that the drive fails to easily read. Many RAID controllers will drop a non-responsive drive in 8 seconds or so. This can cause the array to drop a good drive because it has not been given enough time to complete its internal error recovery procedure, leaving the rest of the array vulnerable. So-called enterprise class drives limit the error recovery time and prevent this problem, but desktop drives can be quite risky for this reason. A fix is known for Western Digital drives. A utility called WDTLER.exe can limit the error recovery time of a Western Digital desktop drive so that it will not be dropped from the array for this reason. The utility enables TLER (time limited error recovery) which limits the error recovery time to 7 seconds. Western Digital enterprise class drives are shipped from the factory with TLER enabled to prevent being dropped from RAID arrays. Similar technologies are used by Seagate, Samsung, and Hitachi.

Increasing recovery time

Drive capacity has grown at a much faster rate than transfer speed, and error rates have only fallen a little in comparison. Therefore, larger capacity drives may take hours, if not days, to rebuild. The re-build time is also limited if the entire array is still in operation at reduced capacity. Given a RAID array with only one disk of redundancy (RAIDs 3, 4, and 5), a second failure would cause complete failure of the array, as the mean time between failure (MTBF) is high.[21]

Other Problems and Viruses

While RAID may protect against drive failure, the data is still exposed to operator, software, hardware and virus destruction. Most well-designed systems include separate backup systems that hold copies of the data, but don't allow much interaction with it. Most copy the data and remove the copy from the computer for safe storage.

History

Norman Ken Ouchi at IBM was awarded a 1978 U.S. patent 4,092,732[22] titled "System for recovering data stored in failed memory unit." The claims for this patent describe what would later be termed RAID 5 with full stripe writes. This 1978 patent also mentions that disk mirroring or duplexing (what would later be termed RAID 1) and protection with dedicated parity (that would later be termed RAID 4) were prior art at that time.

The term RAID was first defined by David A. Patterson, Garth A. Gibson and Randy Katz at the University of California, Berkeley in 1987. They studied the possibility of using two or more drives to appear as a single device to the host system and published a paper: "A Case for Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks (RAID)" in June 1988 at the SIGMOD conference.[1]

This specification suggested a number of prototype RAID levels, or combinations of drives. Each had theoretical advantages and disadvantages. Over the years, different implementations of the RAID concept have appeared. Most differ substantially from the original idealized RAID levels, but the numbered names have remained. This can be confusing, since one implementation of RAID 5, for example, can differ substantially from another. RAID 3 and RAID 4 are often confused and even used interchangeably.

Non-RAID drive architectures

Non-RAID drive architectures also exist, and are often referred to, similarly to RAID, by standard acronyms, several tongue-in-cheek. A single drive is referred to as a SLED (Single Large Expensive Drive), by contrast with RAID, while an array of drives without any additional control (accessed simply as independent drives) is referred to as a JBOD (Just a Bunch Of Disks). Simple concatenation is referred to a SPAN, or sometimes as JBOD, though this latter is proscribed in careful use, due to the alternative meaning just cited.

See also

- Disk Data Format (DDF)

- Disk array controller

- Redundant Array of Inexpensive Nodes

- Vinum volume manager

Developers of Raid Hardware

- 3ware

- Adaptec

- Areca

- Dawicontrol

- EMC

- HighPoint Technologies

- HP

- IBM

- Infortrend

- Intel

- Intelliprop Inc

- Leaf

- LSI

- NEXSAN Technologies

- Promise Technology

- Supermicro

- Xyratex

References

- ^ a b David A. Patterson, Garth Gibson, and Randy H. Katz: A Case for Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks (RAID). University of California Berkley. 1988. Cite error: The named reference "patterson" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Originally referred to as Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks, the concept of RAID was first developed in the late 1980s by Patterson, Gibson, and Katz of the University of California at Berkeley. (The RAID Advisory Board has since substituted the term Inexpensive with Independent.)" Storage Area Network Fundamentals; Meeta Gupta; Cisco Press; ISBN 978-1-58705-065-7; Appendix A.

- ^ See RAS syndrome.

- ^ SNIA Dictionary

- ^ Vijayan, S. (1995). "Dual-Crosshatch Disk Array: A Highly Reliable Hybrid-RAID Architecture". Proceedings of the 1995 International Conference on Parallel Processing: Volume 1. CRC Press. pp. I-146ff. ISBN 084932615X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Main Page - Linux-raid

- ^ Data Robotics, Inc.

- ^ "Apple Mac OS X Server File Systems". Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ "FreeBSD System Manager's Manual page for GEOM(8)". Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "freebsd-geom mailing list - new class / geom_raid5". Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "FreeBSD Kernel Interfaces Manual for CCD(4)". Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "The Software-RAID HOWTO". Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ "RAID setup". Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ Using WindowsXP to Make RAID 5 Happen

- ^ "FreeBSD Handbook". Chapter 19 GEOM: Modular Disk Transformation Framework. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Jim Gray and Catharine van Ingen, "Empirical Measurements of Disk Failure Rates and Error Rates", MSTR-2005-166, December 2005

- ^ Disk Failures in the Real World: What Does an MTTF of 1,000,000 Hours Mean to You? Bianca Schroeder and Garth A. Gibson

- ^ Disk drive failure rates: Fact or fiction?

- ^ Jim Gray: The Transaction Concept: Virtues and Limitations (Invited Paper) VLDB 1981: 144-154

- ^ "Definition of write-back cache at SNIA dictionary".

- ^ RAID's Days May Be Numbered

- ^ US patent 4092732, Norman Ken Ouchi, "System for recovering data stored in failed memory unit", issued 1978-05-30

Further reading

- Charles M. Kozierok (2001-04-17). "Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks". The PC Guide. Pair Networks.

External links

- Tutorial on RAID 6 & performance implications

- Learning about RAID Tutorial, Levels 0, 1, 5, 10, and 50

- RAID at Curlie

- Introduction to RAID

- Working RAID illustrations

- RAID Levels — Tutorial and Diagrams

- Logical Volume Manager Performance Measurement

- Tutorial on Reed-Solomon Coding for Fault-Tolerance in RAID-like Systems

- Parity Declustering for Continuous Operation in Redundant Disk Arrays

- An Optimal Scheme for Tolerating Double Disk Failures in RAID Architectures

- Linux RAID and LVM Management