History of Sesame Street

- This article reflects the history of the American preschool educational television show. For other productions, see International co-productions of Sesame Street.

Sesame Street premiered on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) on November 10, 1969, with a combination of Jim Henson's Muppets, animation, live shorts and cultural references. It was the first preschool educational television program to base its contents and production values on laboratory and formative research, and the first to include a curriculum "detailed or stated in terms of measurable outcomes".[1] Initial responses to the show included adulatory reviews, some controversy, and high ratings. By its 40th anniversary in 2009, Sesame Street was broadcast in over 120 countries, and 20 independent international versions had been produced.[2]

The show was conceived in 1966 during discussions between television producer Joan Ganz Cooney and Carnegie Foundation vice president Lloyd Morrisett. Their goal was to create a children's television show that would "master the addictive qualities of television and do something good with them",[3] such as helping young children prepare for school. After two years of research, the newly formed Children's Television Workshop (CTW) received a combined grant of US$8 million from Carnegie, the Ford Foundation, and the U.S. federal government to create and produce a new children's television show.

Sesame Street has undergone significant changes in its 40-year history. By the show's tenth anniversary in 1979, nine million American children under the age of six were watching Sesame Street daily, and several studies showed its effectiveness. The cast and crew expanded during this time, including the hiring of women in the crew and additional minorities in the cast. The show's success continued into the 1980s. In 1981, the federal government withdrew its funding, so CTW turned to other sources, including the magazine division, book royalties, product licensing, and foreign income. Sesame Street's curriculum has expanded to include more affective topics such as relationships, ethics, and emotions. Many of the show's storylines were taken from the experiences of its writing staff, cast, and crew. Most notable of these are the death of Will Lee—who played Mr. Hooper—and the marriage of Luis and Maria.

In recent decades, Sesame Street has faced societal and economic challenges, including changes in viewing habits of young children, more competition from other shows, the development of cable television, and a drop in ratings. After the turn of the century, the show made major structural changes, including a change from the traditional magazine format to a narrative format. Due to the popularity of the Muppet Elmo, the show also incorporated a popular segment known as "Elmo's World". Sesame Street has won eight Grammys and over a hundred Emmys in its 40-year history—more than any other children's show.

Pre-production (1966-1969)

Beginnings

Until the late 1960s, television programs created for children were widely criticized for being little more than cartoons depicting violence and reflecting commercial values.[4][5] Producer Joan Ganz Cooney called children's programming a "wasteland", and she was not alone in her criticism.[4][5][note 1] Many children's television programs were produced by local stations, with little regard for educational goals.[6][note 2] The concept of children's programming as an educational tool was "unproven", according to author David Borgenicht, and the idea to use it as such was "a revolutionary concept".[4]

According to children's media experts Edward Palmer and Shalom M. Fisch, children's television programs of the 1950s and 1960s duplicated "prior media forms".[7] For example, they tended to show simple shots of a camera's-eye view of a location filled with children, or they recreated storybooks with shots of book covers and motionless illustrated pages. Palmer and Fisch called the hosts of these programs "insufferably condescending".[7] An exception was Captain Kangaroo, which was created and hosted by Bob Keeshan and had, as described by Davis, a "slower pace and idealism" that most other children's shows did not have.[8][note 3] Television historian Cary O'Dell declared that children's television was "in a sad state".[9]

Cooney was producing talk shows and documentaries at educational television station WNDT, and in 1966 had won an Emmy for a documentary about poverty in America.[10] In early 1966, Cooney and her husband Tim hosted a dinner party at their apartment in Manhattan; experimental psychologist Lloyd Morrisett, who has been called Sesame Street's "financial godfather",[11] and his wife Mary were among the guests. Cooney's boss, Lewis Freedman, and their colleague Anne Bower also attended the party.[12] As a vice-president at the Carnegie Institute, Morrisett had awarded several million dollars in grants to organizations involved in the education of preschool children, especially from poor and minority backgrounds. Morrisett and the other guests felt that even with limited resources, television could be an effective way to reach millions of children.[13] A few days after the dinner party, Cooney, Freedman, and Morrisett met at Carnegie's offices to discuss and outline how to "master the addictive qualities of television and do something good with them".[3] The group, financed by Carnegie, hired Cooney in the summer of 1967 to visit experts in childhood development, education, and media across the US and Canada. She researched their ideas about the viewing habits of young children and wrote a report on her findings.[14][15]

In spite of Cooney's lack of experience in the field of education,[16] her study was well received. Titled "Television for Preschool Education",[17] it spelled out how television could be used as an aid in the education of preschool children, especially those living in inner cities.[18][19] Early childhood educational research had shown that when children were prepared to succeed in school, they earned higher grades and learned more effectively. In the late 1960s, however, children from low-income families had fewer resources than children from higher income families to prepare them for school. Research had also shown that children from low-income, minority backgrounds tested "substantially lower"[20] than middle-class children in school-related skills, and that they continued to have educational deficits throughout school.[17]

In the late 1960s, 97% of all American households owned a television set and preschool children watched an average of 27 hours of television per week,[13] making an educational program equally accessible to children of all socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds.[20] Cooney proposed that public television improve the quality of children's programming, and help young children, especially from low-income families, prepare for school. She suggested using the media's "most engaging traits",[21] including its high production values, sophisticated writing, and quality film and animation, to reach the largest audience possible. As New York Magazine television critic Peter Hellman stated, "If [children] could recite Budweiser jingles from TV, why not give them a program that would teach the ABCs and simple number concepts?"[13]

Cooney wanted to create a program that would spread values favoring education to nonviewers—including their parents,[22] so her goal was to produce a show that parents would watch with their children. To this end, she suggested that humor directed toward adults be included.[23] As Hellman put it, "Keeping adults interested is the key to its success".[24] In addition, cultural references and guest appearances from celebrities would encourage parents and older siblings to watch together.[16]

Development

As a result of Cooney's proposal, the Carnegie Institute awarded her an US$8 million grant in 1968 to create a new children's television program and establish the Children’s Television Workshop (CTW).[18][25] Cooney and Morrisett procured additional multi-million-dollar grants from the US federal government, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and the Ford Foundation.[3] The new show had a budget of US$28,000 per episode.[26] After being named executive director of CTW,[27][note 4] Cooney began to assemble a team of producers:[18] Jon Stone was responsible for writing, casting, and format; Connell took over animation and volume; and Gibbon served as the show's chief liaison between the production staff and the research team.[28] They had worked on Captain Kangaroo together, but were not involved in children's television at the time Cooney recruited them.[note 5] At first, Cooney planned to divide up the show's production of five episodes a week among several teams, but was advised by CBS vice-president Mike Dann to use only one team. This production team was led by Connell, who had gained experience producing many episodes in a short period of time (called "volume production") during his eleven years working on Captain Kangaroo.[29]

Harvard University professor Gerald S. Lesser conducted five three-day curriculum planning seminars in Boston in the summer of 1968.[18][31] The purpose of the seminars was to ascertain which school-preparation skills to emphasize in the new show. The producers gathered professionals with diverse backgrounds in order to obtain ideas for educational content. They reported that the seminars were "widely successful",[31] and resulted in long and detailed lists of possible topics for inclusion in the Sesame Street curriculum.[31] The producers also reported that the seminars resulted in more educational objectives than they could ever address. The objectives were condensed into key categories: symbolic representation, cognitive processes, and the physical and social environment.[32][33] Additionally, these seminars set forth the new show's policy about race and social issues[34] and they marked the beginning of Jim Henson's involvement in Sesame Street. Cooney met Henson at one of the seminars; Stone, who was familiar with Henson's work, felt that if they could not bring him on board, they should "make do without puppets".[18]

The producers and writers decided to build the new show around a brownstone or an inner-city street, a choice that Davis called "unprecedented".[35] Stone was convinced that in order for inner-city children to relate to Sesame Street, it needed to be set in a familiar place.[36] The new show was called the "Preschool Educational Television Show" in promotional materials. According to Cooney, they were "frantic for a title".[35] They finally settled upon Sesame Street, and although there had been concerns that it would be too difficult for young children to pronounce, it was the name that they least disliked.[35] Stone was one of the producers who disliked the name, but as he said, "I was outvoted, for which I'm deeply grateful".[37][note 6]

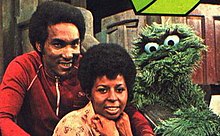

The responsibility of casting for Sesame Street fell to Jon Stone, who set out to cast white actors in the minority.[36] He did not begin auditions until spring 1969, several weeks before five test shows were due to be produced. He filmed the auditions, and Ed Palmer took them into the field to test children's reactions. The actors who received the "most enthusiastic thumbs up" were cast.[35] For example, Loretta Long was chosen to play Susan when the children who saw her audition stood up and sang along with her rendition of "I'm a Little Teapot".[38] As Stone said, casting was the only aspect that was "just completely haphazard".[39] Most of the cast and crew found jobs on Sesame Street through personal relationships with Stone and the other producers.[39] Stone also hired Bob McGrath to play Bob, Will Lee to play Mr. Hooper, and Matt Robinson to play Gordon.[note 7]

Use of research in production

According to Palmer and Fisch, Sesame Street was the first children's television program that included a curriculum "detailed or stated in terms of measurable outcomes".[1] Little precedent for incorporating research into television production existed before the show was first aired.[40] The producers and writers were concerned that the educational goals would limit creativity, but Stone understood that there were infinite ways to express the curriculum onscreen. Researchers were always present in the studio during the show's filming.[20] A "Writer's Notebook" was developed to assist the writers and producers in translating research and production goals into televised material.[41] The Muppet characters, for example, were created to fill specific curriculum needs. Oscar the Grouch was designed to teach children about their positive and negative emotions.[42] As Cooney stated, "From the beginning, we—the planners of the project—designed the show as an experimental research project with educational advisers, researchers, and television producers collaborating as equal partners".[4]

Sesame Street came along and rewrote the book. Never before had anyone assembled an A-list of advisors to develop a series with stated educational norms and objectives. Never before had anyone viewed a children's show as a living laboratory, where results would be vigorously and continually tested. Never before in television had anyone thought to commingle writers and social scientists, a forced marriage that, with surprising ease and good humor, endured and thrived.

—Michael Davis, Street Gang[43]

The producers of Sesame Street used laboratory-oriented research to test the show's ability to hold children's attention. As author Malcolm Gladwell has stated, "Sesame Street was built around a single, breakthrough insight: that if you can hold the attention of children, you can educate them".[44] The researchers involved with the show found that preschoolers are more sophisticated television viewers than originally thought.[45] Edward Palmer, the man Cooney credits with building CTW's foundation of research,[46] was one of the few academics in the late 1960s researching children's television.[47] He was recruited by the CTW to test if the curricula developed in the Boston seminars were reaching their audience effectively.[47] Palmer's research was so crucial to Sesame Street that Gladwell asserted, "...without Ed Palmer, the show would have never lasted through the first season".[47]

Palmer and his team's approach to researching the show's effectiveness was innovative; it was the first time that formative research was conducted in this way.[48] For example, Palmer developed "the distractor method",[47][49] which he used to test if the material shown on Sesame Street captured young viewers' attention. Two children at a time were brought into the laboratory; they were shown an episode on a television monitor and a slide show next to it. The slides would change every seven seconds, and researchers recorded when the children's attention was diverted away from the episode.[40][50] They were able to record almost every second of Sesame Street this way; if the episode captured the children's interest 80%–90% of the time, the producers would air it, but if it only tested 50%, they would re-shoot it. Palmer reported that by the fourth season of the show, the episodes rarely tested below 85%.[51]

July 1969 test episodes

During the production of Sesame Street's first season, producers created five one-hour episodes to test the show's appeal to children, and examine their comprehension of the material. Not intended for broadcast, they were presented to preschoolers in 60 homes throughout Philadelphia in July 1969. According to CTW researchers Shalom M. Fisch and Lewis Bernstein, the results were "generally very positive",[52] demonstrating that children learned from the shows and that their appeal was high. However, the researchers found that although children's attention was high during the Muppet segments, their interest wavered during the "Street" segments. The producers had followed the advice of child psychologists who were concerned that children would be misled and recommended that they never show the human actors and Muppets together. As a result, the appeal of the test episodes was lower than they preferred.[52][53]

Palmer referred to the Street scenes as "the glue" that "pulled the show together",[54] so producers knew that they needed to make significant changes. On the basis of their experience on Captain Kangaroo, Cannell, Stone, and Gibbon thought that the experts' opinions were "nonsense";[55] Cooney agreed.[42] Lesser called their decision to defy the recommendations of their advisers "a turning point in the history of Sesame Street".[54] The producers went back and reshot the Street segments; Henson and his coworkers created Muppets that could interact with the human actors,[54][56] specifically Oscar the Grouch and Big Bird, two of the show's most enduring characters.[48] These test episodes were directly responsible for what Gladwell calls "the essence of Sesame Street—the artful blend of fluffy monsters and earnest adults".[54]

Premiere and first season (1969-1970)

Two days before the show's premiere, a thirty-minute preview entitled This Way to Sesame Street was aired on NBC. The show was financed by a US$50,000 grant from Xerox. Written by Stone and produced by CTW publicist Bob Hatch, it was taped the day before it aired.[57] Newsday called the preview "a unique display of cooperation between commercial and noncommercial broadcasters".[57]

Sesame Street premiered on PBS on November 10, 1969[note 8] and received almost immediate praise. Davis described it as "the rare children's show stamped with parental approval".[58] The show reached only 67.6% of the nation, but earned a 3.3 Nielsen rating, or 1.9 million households. In November of the following year the cover of Time magazine featured Big Bird, who had received more fan mail than any of the show's human hosts. The magazine declared, " ...It is not only the best children's show in TV history, it is one of the best parents' shows as well".[26] David Frost declared Sesame Street "a hit everywhere it goes".[26] An executive at ABC, while recognizing that Sesame Street was not perfect, stated that the show "opened children's TV to taste and wit and substance" and "made the climate right for improvement".[26]

The effectiveness of the show was almost immediately apparent. In Sesame Street's first season, the Educational Testing Service (ETS) reported that the cognitive skills of its young viewers had increased by 62%.[26] They found that children who watched the show scored higher in the ETS' tests than less frequent viewers.[59] The show reached 7 million children a day and Big Bird appeared on The Flip Wilson Show. Also in 1970, Sesame Street won a Peabody Award, three Emmys, and the Prix Jeunesse award. President Richard Nixon sent Cooney a congratulatory letter,[26] while Dr. Benjamin Spock predicted that the program would result in "better-trained citizens, fewer unemployables in the next generation, fewer people on welfare, and smaller jail populations".[60]

But Sesame Street was not without its detractors. In May 1970, a state commission in Mississippi voted to ban the show. A member of the commission leaked the vote to the New York Times, stating that "Mississippi was not yet ready" for the show's integrated cast.[61] Cooney called the ban "a tragedy for both the white and black children of Mississippi".[5] The Mississippi commission later reversed its decision, after the vote made national news. New York Times Magazine later reported that Sesame Street has endured criticism of its frenetic pacing, which was thought to induce epilepsy in its preschool audience.[36]

According to Time, the producers of Sesame Street made a few changes in its second season. Segments that featured children became more spontaneous and allowed for more impromptu dialogue, even when it meant cutting other segments.[26] Since federal funds had been used to produce the show, more segments of the population insisted upon being represented on Sesame Street. For example, the show has been criticized by Hispanic groups for the lack of Latino characters in the early years of production.[5]

While New York Times Magazine reported criticism of the presence of strong single women in the show, organizations like the National Organization for Women (NOW) expressed concerns that the show needed to be "less male-oriented".[26][36] For example, members of NOW took exception to the character Susan, who was originally a housewife.[62] The show's producers satisfied these critics by making Susan a nurse and by hiring a female writer.[26]

1970s

By the mid-1970s, Sesame Street, according to Davis, had "became an American institution".[63] The ETS attempted to study the effects the show had on young children after its second season, but found that the show's popularity weakened their experimental design, requiring a change of research methodologies.[64][note 9] Producer Jon Stone, who "gave Sesame Street its soul",[63] was instrumental in guiding the show during these years. According to Davis, without Stone "there would not have been Sesame Street as we know it".[65] Stone was able to recognize and mentor talented people for his crew. He actively hired and promoted women during a time when few women earned top production jobs in television. As a result, his policies provided the show with a succession of women producers and writers, many of whom went on to lead the boom in children's programming at Nickelodeon, the Disney Channel, and PBS in the 1990s and 2000s. One of these women was Dulcy Singer, who later became the first female executive producer of Sesame Street.[66]

After the the show's initial success, its producers began to think about its survival beyond its development and first season and decided to explore other funding sources.[67] This era in the show's history was marked by conflicts between CTW and the federal government; in 1978, the US Department of Education refused to deliver a US$2 million check until the last day of CTW's fiscal year. As a result, the CTW decided to depend upon licensing arrangements, publishing, and international sales for their funding.[68] Henson owned the trademarks to the Muppet characters, and he was reluctant to market them at first. He agreed when CTW promised that the profits from toys, books, and other products were to be used exclusively to fund CTW. The producers demanded complete control over all products and product decisions; any product line associated with the show had to be educational, inexpensive, and not advertised during its airings.[69] They approached Random House to establish and manage a nonbroadcast materials division. Random House and CTW named Christopher Cerf to assist CTW in publishing books and other material that emphasized the curriculum.[70] In 1980, CTW began to produce "Sesame Street Live", a touring stage production based upon the show, which was written by Connell and performed by the Ice Follies.[71]

Shortly after the premiere of Sesame Street, the CTW was approached by producers, educators, and officials in other nations, requesting that a version of the show be aired in their countries. Former CBS executive Mike Dann, after leaving commercial television to become vice president of CTW and Cooney's assistant, began what Charlotte Cole, vice president for CTW's International Research department, called the "globalization" of Sesame Street.[72] A flexible model, based upon the experiences of the creators and producers of the US show, was developed. The shows came to be called "co-productions", and they contained original sets, characters, and curriculum goals. Depending upon each country's needs and resources, different versions were produced, including dubbed versions of the original show and independent programs. By 2009, Sesame Street had expanded into 140 countries;[73] Doreen Carvajal of The New York Times reported in 2005 that income from CTW's international co-productions of the show accounted for US$96 million.[74]

Sesame Street's cast expanded during this time, better fulfilling the show's original goal of greater diversity in both human and Muppet characters. The cast members who joined the show during this time were Sonia Manzano (Maria), Northern Calloway (David), Alaina Reed (Olivia), Emilio Delgado (Luis), Linda Bove (Linda), and Buffy Sainte-Marie (Buffy).[75] In 1975, Roscoe Orman became the third actor to play Gordon, succeeding Hal Miller, who had briefly replaced Matt Robinson.[76] In addition, new Muppet characters were introduced during the 70s. Count Von Count was created and performed by Jerry Nelson, who also voiced Mr. Snuffleupagus, a muppet that required two puppeteers to operate. Richard Hunt, who, as Jon Stone said, joined the Muppets as a "wild-eyed 18-year-old and grew into a master puppeteer and inspired teacher", created Gladys the Cow, Forgetful Jones, Don Music, and the construction worker Sully.[77] Telly Monster was performed by Brian Muehl; Marty Robinson took over the role in 1984.[78] Frank Oz created Cookie Monster. Matt Robinson created, as Davis called him, the "controversial" character Roosevelt Franklin.[note 10] Fran Brill, the first female puppeteer for the Muppets, joined the Henson organization in 1970.[79] Brill originated the character Prairie Dawn.

The CTW wanted to attract the best composers and lyricists for Sesame Street, so songwriters like Joe Raposo, the show's music director, and writer Jeff Moss were able to retain the rights to the songs they wrote. The writers earned lucrative profits, and the show was able to sustain public interest. Raposo's "I Love Trash", written for Oscar the Grouch, was included on the first album of Sesame Street songs, recorded in 1974. Moss' "Rubber Duckie", sung by Henson for Ernie, remained on the Top-40 charts for seven weeks in 1971.[80] Another Henson song, written by Raposo for Kermit the Frog in 1970, "Bein' Green", which Davis called "Raposo's best-regarded song for Sesame Street",[81] was later recorded by Frank Sinatra and Ray Charles. "Somebody Come and Play" and "Sing", which became a hit for The Carpenters in 1973,[82] were also written by Raposo for Sesame Street.

In 1978, Stone and Singer produced and wrote the show's first special, the "triumphant" Christmas Eve on Sesame Street.[83] Davis stated that the special demonstrated "how remarkably gifted were Jim Henson and Frank Oz, two real-life colleagues and friends, at playing puppetry's Odd Couple" in Bert and Ernie.[84] (This was demonstrated in the special's O Henry-inspired storyline, in which the characters gave up their prized possessions, Ernie his rubber ducky and Bert his paper clip collection, to purchase each other Christmas gifts.) Singer reported that the special also demonstrated Stone's "soul", and Sonia Manzano called it a good example of what Sesame Street was all about. By the show's tenth anniversary in 1979, nine million American children under the age of six were watching Sesame Street daily. Four out of five children had watched it over a six-week period, and 90% of children from low-income inner-city homes regularly viewed the show.[85]

1980s

In 1984, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) deregulated commercial restrictions on children's television. Advertising during network children's programs almost doubled, and deregulation resulted in an increase in commercially oriented programming. According to Hellman, Sesame Street was successful during this era of deregulation, in spite of the fact that the US government terminated all federal funding of CTW in 1981.[68] By 1987, the show had earned US$42 million from its magazine division, book royalties, product licensing, and foreign income—enough to cover two-thirds of its expenses. Its remaining budget, plus a US$6 million surplus, was covered by revenue from its PBS broadcasts.[13]

According to Davis, Sesame Street's second decade was spent "turning inward, expanding its young viewers' world".[85] The show's curriculum expanded to include more "affective" teaching—relationships, ethics, and positive and negative emotions.[36] Many of the show's storylines were taken from the experiences of its writing staff, cast, and crew. In 1982, Will Lee, who had played Mr. Hooper since the show's premiere, died. For the 1983 season, the show's producers and research staff decided that instead of recasting the role, they would explain Mr. Hooper's death to their preschool audience. They also decided to honor Lee's memory, who, as the episode's writer Norman Stiles stated, was "a man we respected and loved".[36] They convened a group of psychologists, religious leaders, and other experts in the field of grief, loss, and separation. The research team conducted a series of studies before the episode aired to ascertain if children were able to understand the messages they wanted to convey about Mr. Hooper's death; the research showed that most children did. Parents' reactions to the episode were, according to CTW's own reports, "overwhelmingly positive".[86] The episode aired on Thanksgiving Day in 1983 so that parents could be home to discuss it with their children. Author David Borgenicht called the episode "poignant";[87] Davis called it "a landmark broadcast"[88] and "a truly memorable episode, one of the show's best".[89] Carroll Spinney, who played Big Bird and who drew the caricatures prominently used in the episode, reported that the cast and crew were moved to tears while filming the episode.[note 11]

"To look back at that period [the 1980s] is to appreciate the profound effect that life-cycle events had on the show, offstage and on. There was birth and death, love and loss, courtship, and calamity, pain and pleasure, all from a little show whose aims at first were simply to test television's ability to stimulate the brain. That it would also touch the heart was not its original intention, but as each year passed, Sesame Street became as much an emotional pathway for children as an intellectual one".

-Michael Davis, Street Gang, p. 277

In the mid 80s, the US was becoming more aware of the prevalence of child abuse, so Sesame Street's researchers and producers decided to "reveal" Big Bird's imaginary friend, Mr. Snuffleupagus, to the adults on the show in 1985.[90] They were concerned about the message being sent to children; "If children saw that the adults didn't believe what Big Bird said (even though it was true), they would be afraid to talk to adults about dramatic or disturbing things that happened to them".[91]

Sesame Street's producers and writers began to use their cast member's personal lives and real-life experiences to cover issues they wanted to address on the show. For the 1988 and 1989 seasons, the topics of love, marriage, and childbirth were addressed when they created a storyline in which the characters Luis and Maria fall in love, marry, and have a child, Gabi. Sonia Manzano, the actress who played Maria, had married and become pregnant; according to the book Sesame Street Unpaved, published after the show's thirtieth anniversary in 1999, Manzano's real-life experiences gave the show's writers and producers the idea.[92] Research was done before any scripts were written to gain an understanding of the previous studies about preschoolers' understanding of love, marriage, and family. The show's research staff found that at the time, there was very little relevant research done about children's understanding of these topics, and no books for children had been written about them.[86] Research was also conducted by Sesame Street in order to target the areas in which children's knowledge was the weakest. Studies done after the episodes about Maria's pregnancy aired showed that as a result of watching these episodes, children's understanding of pregnancy increased.[93][note 12]

1990s

As Davis reported, "the nineties were a time of transition on Sesame Street".[94] Several people involved in the show from its beginnings died during this period: Jim Henson in 1990 at the age of 53 "from a runaway strep infection gone stubbornly, foolishly untreated";[95][note 13] songwriter Joe Raposo from non-Hodgkin's lymphoma fifteen months earlier;[96] long-time cast member Northern Calloway of cardiac arrest in January 1990;[94][note 14] puppeteer Richard Hunt of AIDS in early 1992;[77] CTW founder and producer David Connell of bladder cancer in 1995;[97] director Jon Stone of Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 1997;[98] and writer Jeff Moss of colon cancer in 1998.[99]

By the early 1990s, Sesame Street was, as Davis put it, "the undisputed heavyweight champion of preschool television".[100] Entertainment Weekly reported in 1991 that the show's music had been honored with eight Grammys.[101] The show's dominance was challenged by another PBS television show for preschoolers, Barney & Friends, and Sesame Street's ratings declined. The producers of Sesame Street responded, at the show's twenty-fifth anniversary in 1993, by expanding and re-designing the show's set, calling it "Around the Corner".[102] New human and Muppet characters were introduced, including Zoe (performed by Fran Brill), baby Natasha and her parents Ingrid and Humphrey, and Ruthie (played by comedian Ruth Buzzi).[103] The character Zoe was created to include more female Muppets on the show and to break female stereotypes.[104] According to Michael Davis, she was also the first character created on the show by marketing and product development specialists, who worked with the researchers at CTW.[105] (The quest for a "break-out" female Muppet character continued into 2006 with the creation of Abby Cadabby, who was created after nine months of research.)[106] The "Around the Corner" set was dismantled in 1997.[107] For the first time in the show's history, Sesame Street pursued funding by accepting corporate sponsorship in 1998. Consumer advocate Ralph Nader, who had been a guest on the show, urged parents to protest the move by boycotting the show.[108]

For Sesame Street's 30th anniversary in 1999, its producers researched the reasons for the show's lower ratings. For the first time since the show debuted, the producers and a team of researchers analyzed Sesame Street's content and structure during a series of two-week long workshops. They also studied how children's viewing habits had changed in the past thirty years. They found that although the show was produced for those between the ages of three and five, children began watching it at a younger age. Preschool television had become more competitive, and had shown that the traditional magazine-format was not the best way to attract young children's attention. The growth of home-videos during the 80s and the increase of thirty-minute children's shows on cable had demonstrated that programs lasting ninety minutes or more could hold the attention of young children. The CTW's researchers had found that interest declined for Sesame Street's younger viewers after 40–45 minutes.[109][110] As a result, the target age for Sesame Street shifted downward, from four years to three years, and a part of each episode targeted the developmental age of these newer viewers. A new 15-minute long segment shown at the end of each episode, "Elmo's World", used traditional elements (animation, Muppets, music, and live-action film), but had a more sustained narrative.[111] "Elmo's World" also followed the same structure each episode, and depended heavily on repetition.[112][note 15] Unlike the realism of the rest of the show, the segment took place in a stylized crayon-drawing universe as conceived by its host.[113]

Elmo, who represented the younger audience, was chosen as the host of the closing segment because younger toddlers identified with him[114] and because he had always tested well with them.[112] He was created in 1979 and performed by various puppeteers, including Richard Hunt, but did not become what his eventual portrayer, Kevin Clash, called a "phenomenon"[4] until Clash took over the role in 1983. Eventually, Elmo became, as Davis reported, "the embodiment" of Sesame Street, and "the marketing wonder of our age"[115] when 5 million "Tickle Me Elmo" dolls were sold in 1996. Clash believes that the "Tickle Me Elmo" phenomenon made Elmo a household name and led to the "Elmo's World" segment.[116]

2000s

In 2002, Sesame Street's producers went further in changing the show to reflect its younger demographic, fundamentally changing the show's structure, which had relied on "Street scenes" interrupted by live-action videos and animation. They decided, after the show's 33rd season, to expand upon the "Elmo's World" concept by doing what San Francisco Chronicle television critic Tim Goodman called "deconstructing"[117] the show. They changed from a magazine format to a narrative format, and made the show easier for young children to navigate. Arlene Sherman, a co-executive producer for 25 years, called the show's new look "startlingly different".[117] Following its tradition of addressing emotionally difficult topics, Sesame Street's producers chose to address the attacks of 9/11 during this season on its premiere episode, which aired on February 4, 2002.[5]

In 2006, the U.S. State Department called Sesame Street "the most widely viewed children's television show in the world".[2] Over half of the show's international co-productions were made after 2001; according to the 2006 documentary The World According to Sesame Street, the events of 9/11 inspired the producers of these co-productions. In 2003, Takalani Sesame, a South African co-production, elicited criticism in the US when its producers created Kami. The first HIV-positive Muppet, Kami was created with the hope of educating children in South Africa about the epidemic of AIDS. The controversy, which surprised the Sesame Workshop, was short-lived and died down after Kofi Anan and Jerry Falwell praised the Workshop's efforts.[118] Also by 2006, Sesame Street had won more Emmys than any other children's show, including the outstanding children's series award twelve times, each year of its presentation.[119] By 2009, the show had won 118 Emmys, and was awarded the Outstanding Achievement Emmy for its 40 years on the air.[120]

By Sesame Street's 40th anniversary, it was ranked the fifteenth most popular children's show on television. When the show premiered in 1969, 130 episodes a year were produced; in 2009, twenty-six episodes were made. Also by 2009, the Children's Television Workshop, which had changed its name to the Sesame Workshop (SW) in 2000,[27] sought to remain current in the digital age by launching a website with a library of free video clips and free podcasts from throughout the show's history.

The 2008-2009 recession, which injured many nonprofit arts organizations, also affected Sesame Street; in the spring of 2009, the SW had to lay off twenty percent of its staff.[5] Sesame Street's 40th anniversary was commemorated by the 2008 publication of Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street, by Michael Davis, which has been called "the definitive statement" about the history of the show.[121]

Footnotes

- ^ FCC chairman Newton Minow had called television a "vast wasteland" in 1961. Newton N. Minow, "Television and the Public Interest", address to the National Association of Broadcasters, Washington, D.C., May 9, 1961.

- ^ See Davis, pp. 30-41, and Palmer & Fisch, pp. 6-7, for a discussion about the state of children's television programming.

- ^ Much of Keeshan's staff, such as Jon Stone, Tom Whedon, Norton Wright, David Connell, Sam Gibbon, (See Davis, chapter 3, pp. 30-60) and Kevin Clash (Lee, Felicia R. (2006-08-23). "Tickled red to be Elmo in a rainbow world". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-15.) would later work on Sesame Street.

- ^ As one of the first women executives in American television, Cooney's appointment was called "one of the most important television developments of the decade". See Davis, p. 128-129

- ^ See Davis, chapter 10, pp. 130-145. Cooney later said about Sesame Street's original team of producers, "collectively, we were a genius".[1]

- ^ Several names were suggested, including Stone's favorite, 123 Avenue B, but it was rejected because it sounded too much like a New York City address (Davis, p. 156).

- ^ See Davis, pp. 172-182

- ^ See Davis, pp. 192-194 for a description of the first episode, which was sponsored by the letters W, S, and E and the numbers 2 and 3.

- ^ Instead of comparing viewers with a control group of non-viewers, the researchers studied the differences among levels of viewing. They found that children who watched Sesame Street more frequently had a higher comprehension of the material presented than children who watched it less often. (See Mielke, p. 86-87.)

- ^ See Davis, pp. 247-250, for a discussion about Roosevelt Franklin.

- ^ For a description of this episode, see Borgenicht, p. 42, and Davis, pp. 281-285.

- ^ See Truglio et al., pp. 74-76, for a more detailed discussion. Also see Hellman, p. 53 and Davis, pp. 293-294, for a description of the wedding episode, written by Jeff Moss, and Borgenicht, pp. 80-81, for descriptions of the wedding and of Gabi's birth.

- ^ Davis described Henson's death as "shocking". See Davis, pp. 300-307 for a description of Henson's "moving" memorial service, held at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan on May 21, 1990.

- ^ Calloway had suffered from mental illness for many years (Davis, p. 269).

- ^ At first, the same segment was repeated daily for a week, but this practice was dropped at the end of the first season of "Elmo's World".

Notes

- ^ a b Palmer & Fisch, p. 9

- ^ a b Friedman, Michael Jay (2006-04-08). "Sesame Street educates and entertains internationally: Honored children's show honored throughout the world". America.gov. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 8

- ^ a b c d e Borgenicht, p. 9 Cite error: The named reference "page9" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f Guernsey, Lisa (2009-05-23). "'Sesame Street': The show that counts". Newsweek. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ^ Palmer & Fisch, p. 7

- ^ a b Palmer & Fisch, p. 6

- ^ Davis, p. 30

- ^ O'Dell, p. 67

- ^ O'Dell, p. 68

- ^ Davis, p. 7

- ^ Davis, pp. 11-13

- ^ a b c d Hellman, p. 50

- ^ Davis, p. 65

- ^ Morrow, Robert W (2006). Sesame Street and the reform of children's television. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press. p. 47. ISBN 0801882303.

- ^ a b Hymowitz, Kay S. (Autumn 1995). "On Sesame Street, it's all show". City Journal. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ^ a b Lesser & Schneider, p. 26

- ^ a b c d e Finch, p. 53

- ^ Truglio & Fisch, p. xvi

- ^ a b c Palmer & Fisch, p. 5

- ^ Cooney, p. xi

- ^ Gladwell, p. 89

- ^ Gladwell, p. 112

- ^ Hellman, p. 48

- ^ Palmer & Fisch, p. 3

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kanfer, Stefan (1970-11-23). "Who's afraid of big, bad TV?". Time. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- ^ a b O'Neil, William J (2003). Business leaders and success: 55 top business leaders and how they achieved greatness. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 147. ISBN 0-0714-6809.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Davis, p. 147

- ^ Hellman, p. 51

- ^ Finch, p. 54

- ^ a b c Lesser & Schneider, p. 27

- ^ Lesser & Schneider, p. 28

- ^ Borgenicht, p. 14

- ^ Davis, p. 142

- ^ a b c d Davis, p. 156

- ^ a b c d e f Hellman, p. 52

- ^ Finch, p. 55

- ^ Davis, p. 172

- ^ a b Davis, p. 167

- ^ a b Palmer & Fisch, p. 14

- ^ Palmer & Fisch, p. 10

- ^ a b Borgenicht, p. 16

- ^ Davis, p. 118

- ^ Gladwell, p. 100

- ^ Gladwell, p. 101

- ^ Palmer & Fisch, p. 4

- ^ a b c d Gladwell, p. 102

- ^ a b Fisch & Bernstein, p. 40

- ^ Palmer & Fisch, p. 15

- ^ Gladwell, pp. 102-103

- ^ Gladwell, p. 103

- ^ a b Fisch & Bernstein, p. 39

- ^ Gladwell, p. 105

- ^ a b c d Gladwell, p. 106

- ^ Davis, p. 363

- ^ Fisch & Bernstein, pp. 39-40

- ^ a b Davis, p. 189

- ^ Davis, p. 197

- ^ Mielke, p. 87

- ^ Davis, p. 198

- ^ "Mississippi agency votes for a TV ban on 'Sesame Street"". New York Times. 1970-05-03.

- ^ Davis, p. 213

- ^ a b Davis, p. 220

- ^ Mielke, p. 86

- ^ Davis, p. 271

- ^ Davis, p. 221

- ^ Davis, p. 203

- ^ a b O'Dell, Cary (1997). Women pioneers in television: Biographies of fifteen industry leaders. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. pp. 73–74. ISBN 0-7864-0167-2.

- ^ Davis, pp. 203-205

- ^ Davis, p. 205

- ^ Hoover, Bob (1988-01-16). "'Sesame Street' success travels well on the road". Pittsburg Post-Gazette. p. 13. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ^ Cole, Charlotte F (2001). "The world of Sesame Street research". In Fisch, Shalom M (ed.). "G" is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. p. 148. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Giklow, Louise A (2009). Sesame Street: A celebration—Forty years of life on the street. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-57912-638-4.

- ^ Carvajal, Doreen (2005-12-12). "Sesame Street goes global: Let's all count the revenue". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ Davis, pp. 226-237

- ^ Rayworth, Melissa (2009-01-11). "'Sesame Street' role model 'Gordon' is touchstone for generations of young parents". Times Record News. Associated Press. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ^ a b Associated Press (1992-01-09). "Richard Hunt, Henson protege who became a master puppeteer". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ^ Davis, p. 245

- ^ Davis, p. 251

- ^ Whitburn, p. 259

- ^ Davis, p. 256

- ^ Whitburn, p. 788

- ^ Davis, p. 273

- ^ Davis, p. 275

- ^ a b Davis, p. 277

- ^ a b Truglio, et al., p. 74

- ^ Borgenicht, p. 42

- ^ Davis, p. 284

- ^ Davis, p. 281

- ^ Borgenicht, pp. 38-41

- ^ Borgenicht, p. 41

- ^ Borgenicht, p. 80

- ^ Truglio et al., p. 76

- ^ a b Davis, p. 295

- ^ Davis, p. 1

- ^ Davis, pp. 307-308

- ^ Davis, p. 327

- ^ Davis, p. 331

- ^ Davis, p. 335

- ^ Davis, p. 317

- ^ Kohn, Martin F (1991-03-08). "Grammy's greatest (children's) hits". Entertainment Weekly (56): 18. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Davis, p. 320

- ^ Associated Press (1993-05-24). "Sesame Street will go 'Around the corner'". Bryan Times. p. 11. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ Srianthi, Perera (2007-12-27). "'Street' cred: Kids' reaction rewarding to Muppet creator". Arizona Republic. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ Davis, p. 321

- ^ Dominus, Susan (2006-08-06). "A girly-girl joins the 'Sesame' boys". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ^ Davis, p. 330

- ^ Brooke, Jill (1998-11-13). "'Sesame Street' takes a bow to 30 animated years". CNN. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ^ Davis, p. 338

- ^ Fisch & Bernstein, pp. 44-45

- ^ Fisch & Bernstein, p. 45

- ^ a b Whitlock, Natalie Walker. "How Elmo works". How Stuff Works. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ^ Clash, p. 75

- ^ Clash, pp. 46-47

- ^ Davis, p. 249

- ^ Clash, p. 47

- ^ a b Goodman, Tim (2002-02-04). "Word on the 'Street': Classic children's show to undergo structural changes this season". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ^ Knowlton, Linda Goldstein and Linda Hawkins Costigan (producers) (2006). The world according to Sesame Street (documentary). Participant Productions.

- ^ Hill, Lee Alan (2006-05-08). "'Sesame Street's' streak unbroken". Television Week. 25 (19): 18.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "36th daytime Emmy awards". 2009-08-30. The CW.

{{cite episode}}: Missing or empty|series=(help) - ^ Fitzgerald, Judith (2009-03-01). "Count this: 40 years of 'Sesame'". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

References

- Borgenicht, David (1998). Sesame Street unpaved. New York: Hyperion Publishing. ISBN 0786864605

- Clash, Kevin and Gary Brozek & Louis Henry Mitchell (2006). My life as a furry red monster: What being Elmo has taught me about life, love and laughing out loud. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-7679-2375-8

- Cooney, Joan Ganz (2001). "Foreward". In "G" is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street, Fisch, Shalom M. and Rosemarie T. Truglio, eds. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1

- Davis, Michael (2008). Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 9780670019960

- Finch, Christopher (1993). Jim Henson: The works: the art, the magic, the imagination. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-6794-1203-4

- Fisch, Shalom M. and Lewis Bernstein (2001). "Formative research revealed: Methodological and process issues in formative research". In "G" is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street, Fisch, Shalom M. and Rosemarie T. Truglio, eds. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1

- Gladwell, Malcolm (2000). The tipping point: How little things can make a big difference. New York: Little, Brown, and Company. ISBN 0-316-31696-2

- Hellman, Peter. (November 23, 1987). "Street smart: How Big Bird & Co. do it". In New York Magazine, Vol. 20, No. 46, pp. 48-53.

- Lesser, Gerald S. and Joel Schneider (2001). "Creation and evolution of the Sesame Street curriculum". In "G" is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street, Fisch, Shalom M. and Rosemarie T. Truglio, eds. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1

- Mielke, Keith W. (2001). "A review of research on the educational and social impact of Sesame Street." In "G" is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street, Fisch, Shalom M. and Rosemarie T. Truglio, eds. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1

- O'Dell, Cary (1997). Women pioneers in television: Biographies of fifteen industry leaders. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0167-2.

- Palmer, Edward L. and Shalom M. Fisch (2001). "The beginnings of Sesame Street Research". In "G" is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street, Fisch, Shalom M. and Rosemarie T. Truglio, eds. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1

- Truglio, Rosemarie T. and Shalom M. Fisch (2001). "Introduction". In "G" is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street, Fisch, Shalom M. and Rosemarie T. Truglio, eds. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1

- Truglio, Rosemarie T. and Valeria O. Lovelace, Ivelisse Seqhi, & Susan Scheiner (2001). "The varied role of formative research: Case studies from 30 years". In "G" is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street, Fisch, Shalom M. and Rosemarie T. Truglio, eds. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1

- Whitburn, Joel (2004). The Billboard book of top 40 hits, 8th edition. New York: Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-7499-4

External links

- Street Gang (2008 book by Michael Davis) website

- 1970 Time Magazine cover (featuring Big Bird)

- Mr. Hooper's death (YouTube clip)