Copper(II) chloride

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Copper(II) chloride

Copper dichloride | |

| Other names

Cupric chloride

| |

| Identifiers | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.373 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| CuCl2 | |

| Molar mass | 134.45 g/mol (anhydrous) 170.48 g/mol (dihydrate) |

| Appearance | yellow-brown solid (anhydrous) blue-green solid (dihydrate) |

| Density | 3.386 g/cm3 (anhydrous) 2.51 g/cm3 (dihydrate) |

| Melting point | 498 °C (anhydrous) 100 °C (dehydration of dihydrate) |

| Boiling point | 993 °C (anhydrous, decomp) |

| 70.6 g/100 mL (0 °C) 75.7 g/100 mL (25 °C) | |

| Structure | |

| distorted CdI2 structure | |

| Octahedral | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Copper(II) fluoride Copper(II) bromide |

Other cations

|

Copper(I) chloride Silver chloride Gold(III) chloride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Copper(II) chloride is the chemical compound with the formula CuCl2. This is a light green solid, much like neon green, which slowly absorbs moisture to form a blue-green dihydrate.

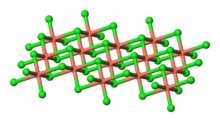

Structure

Anhydrous CuCl2 adopts a distorted cadmium iodide structure. Most copper(II) compounds exhibit distortions from idealized octahedral geometry due to the Jahn-Teller effect, which in this case describes the localisation of one d-electron into a molecular orbital that is strongly antibonding with respect to a pair of ligands. In CuCl2(H2O)2 the copper can be described as a highly distorted octahedral complex, the Cu(II) center being surrounded by two water ligands and four chloride ligands, which bridge asymmetrically to other Cu centers.[1]

Properties

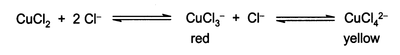

Copper(II) chloride dissociates in aqueous solution to give the blue color of [Cu(H2O)6]2+ and yellow or red color of the halide complexes of the formula [CuCl2+x]x-. Concentrated solutions of CuCl2 appear green because of the combination of these various chromophores. The color of the dilute solution depends on temperature, being green around 100 °C and blue at room temperature.[2] When copper(II) chloride is heated in a flame, it emits a green-blue colour. It is toxic and is only allowed in water in a concentration below 5ppm by the EPA.

It is a weak Lewis acid, and a mild oxidizing agent. It has a crystal structure consisting of polymeric chains of flat CuCl4 units with opposite edges shared. It decomposes to CuCl and Cl2 at 1000 °C:

In its reaction with HCl (or other chloride sources) to form the complex ions CuCl3- and CuCl42-.[3]

Some of these complexes can be crystallized from aqueous solution, and they adopt a wide variety structural types (Fig. 1).

Copper(II) chloride also forms a rich variety of other coordination complexes with ligands such as pyridine or triphenylphosphine oxide:

- CuCl2 + 2 C5H5N → [CuCl2(C5H5N)2] (tetragonal)

- CuCl2 + 2 (C6H5)3P=O → [CuCl2((C6H5)3P=O)2] (tetrahedral)

However "soft" ligands such as phosphines (e.g., triphenylphosphine), iodide, and cyanide as well as some tertiary amines cause reduction to give copper(I) complexes. To convert copper(II) chloride to copper(I) derivatives it is generally more convenient to reduce an aqueous solution with the reducing agent sulfur dioxide:

CuCl2 can simply react as a source of Cu2+ in precipitation reactions for making insoluble copper(II) salts, for example copper(II) hydroxide, which can then decompose above 30 °C to give copper(II) oxide:

Followed by

Preparation

Copper(II) chloride is prepared by the action of hydrochloric acid on copper(II) oxide, copper(II) hydroxide or copper(II) carbonate, for example:

Anhydrous CuCl2 may be prepared directly by union of the elements, copper and chlorine.

CuCl2 may be purified by crystallisation from hot dilute hydrochloric acid, by cooling in a CaCl2-ice bath.[4]

Electrolysis of aqueous sodium chloride with copper electrodes produces (among other things) CuCl2 as a blue-green foam that can be skimmed off the top, collected, and dried to the hydrate.

Mixture of solutions of readily available copper II sulfate and sodium chloride yield a solution of copper II chloride. The sodium sulfate is an inert compound that does not generally enter any reaction.

Uses

A major industrial application for copper(II) chloride is as a co-catalyst (along with palladium(II) chloride) in the Wacker process. In this process, ethene (ethylene) is converted to ethanal (acetaldehyde) using water and air. In the process PdCl2 is reduced to Pd, and the CuCl2 serves to re-oxidise this back to PdCl2. Air can then oxidise the resultant CuCl back to CuCl2, completing the cycle.

(1) C2H4(g) + PdCl2(aq) + H2O (l) → CH3CHO (aq) + Pd(s) + 2 HCl(aq)

(2) Pd(s) + 2 CuCl2(aq) → 2 CuCl(s) + PdCl2(aq)

(3) 2 CuCl(s) + 2 HCl(aq) +1/2O2(g) → 2 CuCl2(aq) + H2O(l)

Overall process: C2H4 +1/2O2 → CH3CHO

Copper(II) chloride has a variety of applications in organic synthesis.[4] It can effect chlorination of aromatic hydrocarbons- this is often performed in the presence of aluminium oxide. It is able to chlorinate the alpha position of carbonyl compounds:[5]

This reaction is performed in a polar solvent such as DMF, often in the presence of lithium chloride, which speeds up the reaction rate.

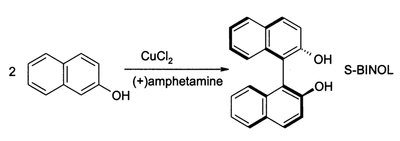

CuCl2, in the presence of oxygen, can also oxidise phenols. The major product can be directed to give either a quinone or a coupled product from oxidative dimerisation. The latter process provides a high-yield synthesis of 1,1-binaphthol (also called BINOL) and its derivatives, these can even be made as a single enantiomer in high enantiomeric excess:[6]

Such compounds are valuable intermediates in the synthesis of BINAP and its derivatives, popular as chiral ligands for asymmetric hydrogenation catalysts.

CuCl2 also catalyses the free radical addition of sulfonyl chlorides to alkenes; the alpha-chlorosulfone may then undergo elimination with base to give a vinyl sulfone product.

Copper(II) chloride is also used in pyrotechnics as a blue/green coloring agent.

Copper chloride is also used as a root killer in landscaping and sewer line maintenance.

A voltaic cell may be made with a copper or brass electrode, copper II chloride, sodium chloride and zinc chloride-soaked papers, and a zinc electrode. These components must be stacked in the order given. It produces 0.84V at 150 milliamps.

Natural occurrence

Copper(II) chloride occurs naturally as the very rare mineral tolbachite and the dihydrate eriochalcite. Both are known from fumaroles. More common are mixed oxyhydroxide-chlorides like atacamite Cu2(OH)3Cl, arising among Cu ore beds oxidation zones in arid climate (also known from some altered slags).

References

- ^ Wells, A.F. (1984) Structural Inorganic Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.

- ^ Alfred Swaine Taylor; Robert Eglesfeld Griffith. On Poisons, in Relation to Medical Jurisprudence and Medicine. Lea & Blanchard, 1848, p. 378.

- ^ OJ SIMPSON (1967). "Tetrahalo Complexes of Dipositive Metals in the First Transition Series". Inorg. Synth. 9: 136–142. doi:10.1002/9780470132401.ch37.

- ^ a b S. H. Bertz, E. H. Fairchild, in Handbook of Reagents for Organic Synthesis, Volume 1: Reagents, Auxiliaries and Catalysts for C-C Bond Formation, (R. M. Coates, S. E. Denmark, eds.), pp. 220-3, Wiley, New York, 1999.

- ^ C. E. Castro, E. J. Gaughan, D. C. Owsley (1965). "Cupric Halide Halogenations". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 30: 587. doi:10.1021/jo01013a069.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J. Brussee, J. L. G. Groenendijk, J. M. Koppele, A. C. A. Jansen (1985). "On the mechanism of the formation of s(−)-(1, 1'-binaphthalene)-2,2'-diol via copper(II)amine complexes". Tetrahedron. 41: 3313. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)96682-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Lide, David R. (1990). CRC handbook of chemistry and physics: a ready-reference book of chemical and physical data. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0471-7.

- The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merck & Co, Rahway, New Jersey, USA, 1960.

- D. Nicholls, Complexes and First-Row Transition Elements, Macmillan Press, London, 1973.

- A. F. Wells, 'Structural Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1984.

- J. March, Advanced Organic Chemistry, 4th ed., p. 723, Wiley, New York, 1992.

- Fieser & Fieser Reagents for Organic Synthesis Volume 5, p158, Wiley, New York, 1975.

- D. W. Smith (1976). "Chlorocuprates(II)". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 21 (2–3): 93–158. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(00)80445-2.