Passenger pigeon

| Passenger Pigeon | |

|---|---|

| |

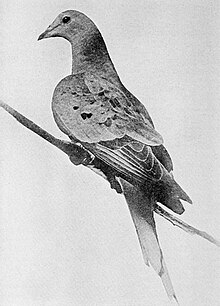

| Live passenger pigeon in 1896 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Ectopistes Swainson, 1827

|

| Species: | E. migratorius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ectopistes migratorius (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

The passenger pigeon or wild pigeon was a species of bird, Ectopistes migratorius, that was once common in North America. It lived in enormous migratory flocks — sometimes containing more than two billion birds — that could stretch one mile (1.6 km) wide and 300 miles (500 km) long across the sky, sometimes taking several hours to pass.[1][2]

Some estimate that there were three billion to five billion passenger pigeons in the United States when Europeans arrived in North America.[3] Others argue that the species had not been common in the Pre-Columbian period, but their numbers grew when devastation of the American Indian population by European diseases led to reduced competition for food.[4]

The species went from being one of the most abundant birds in the world during the 19th century to extinction early in the 20th century.[5] At the time, passenger pigeons had one of the largest groups or flocks of any animal, second only to the Rocky Mountain locust.

Some reduction in numbers occurred because of habitat loss when the Europeans started settling further inland. The primary factor emerged when pigeon meat was commercialized as a cheap food for slaves and the poor in the 19th century, resulting in hunting on a massive scale. There was a slow decline in their numbers between about 1800 and 1870, followed by a catastrophic decline between 1870 and 1890.[6] Martha, thought to be the world's last passenger pigeon, died on September 1, 1914, in Cincinnati, Ohio.

In the 18th century, the passenger pigeon in Europe was known to the French as tourtre; but, in New France, the North American bird was called tourte. In modern French, the bird is known as the pigeon migrateur.

In Algonquian languages, it was called amimi by the Lenape and omiimii by the Ojibwe. The term passenger pigeon in English derives from the French word passager, meaning to pass by.

Description

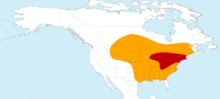

During summer, passenger pigeons lived in forest habitats throughout North America east of the Rocky Mountains: from eastern and central Canada to the northeast United States. In the winters, they migrated to the southern U.S. and occasionally to Mexico and Cuba.

The passenger pigeon was a very social bird. It lived in colonies stretching over hundreds of square miles, practicing communal breeding with up to a hundred nests in a single tree. Pigeon migration, in flocks numbering billions, was a spectacle without parallel:

Early explorers and settlers frequently mentioned passenger pigeons in their writings. Samuel de Champlain in 1605 reported "countless numbers," Gabriel Sagard-Theodat wrote of "infinite multitudes," and Cotton Mather described a flight as being about a mile in width and taking several hours to pass overhead. Yet by the early 1900s no wild passenger pigeons could be found.

— The Smithsonian Encyclopedia[3]

Taxonomy

The species were members of the Columbidae family, pigeons and doves, that has been assigned to the genus Ectopistes. Earlier descriptions of the species placed the population with the genus Columba, but it was tranferred to a monotypic genus due to the greater length of the tail and wings. The generic epithet translates as 'wandering about', the specific indicates that it migratory; the Passenger Pigeon's movements were not only seasonal, as with other birds, they would amass in whatever location was most productive and suitable for breeding.[7]

Causes of extinction

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

The extinction of the passenger pigeon has multiple causes. Previously, the primary cause was held to be the commercial exploitation of pigeon meat on a massive scale.[3] Current examination focuses on the pigeon's loss of habitat.

Even prior to colonization, Native Americans occasionally used pigeons for meat. In the early 1800s, commercial hunters began netting and shooting the birds to sell in the city markets as food, as live targets for trap shooting and even as agricultural fertilizer.

Once pigeon meat became popular, commercial hunting started on a prodigious scale. The bird painter John James Audubon described the preparations for slaughter at a known pigeon-roosting site:

"Few pigeons were then to be seen, but a great number of persons, with horses and wagons, guns and ammunition, had already established encampments on the borders. Two farmers from the vicinity of Russelsville, distant more than a hundred miles, had driven upwards of three hundred hogs to be fattened on the pigeons which were to be slaughtered. Here and there, the people employed in plucking and salting what had already been procured, were seen sitting in the midst of large piles of these birds. The dung lay several inches deep, covering the whole extent of the roosting-place."[8]

Pigeons were shipped by the boxcar-load to the Eastern cities. In New York City, in 1805, a pair of pigeons sold for two cents. Slaves and servants in 18th and 19th century America often saw no other meat. By the 1850s, it was noticed that the numbers of birds seemed to be decreasing, but still the slaughter continued, accelerating to an even greater level as more railroads and telegraphs were developed after the American Civil War.

Another significant reason for its extinction was deforestation. The birds traveled and reproduced in prodigious numbers, satiating predators before any substantial negative impact was made in the bird's population. As their numbers decreased along with their habitat, the birds could no longer rely on high population density for protection. Without this mechanism, many ecologists believe, the species could not survive.

The birds may have suffered from Newcastle disease, an infectious bird disease that was introduced to North America; though the disease was identified in 1926, it has been posited as one of the factors leading to the extinction of the passenger pigeon.

Attempts at preservations

In 1857, a bill was brought forth to the Ohio State Legislature seeking protection for the passenger pigeon. A Select Committee of the Senate filed a report stating "The passenger pigeon needs no protection. Wonderfully prolific, having the vast forests of the North as its breeding grounds, traveling hundreds of miles in search of food, it is here today and elsewhere tomorrow, and no ordinary destruction can lessen them, or be missed from the myriads that are yearly produced."[9]

Attempts to revive the species by breeding the surviving captive birds were not successful. The passenger pigeon was a colonial and gregarious bird practicing communal roosting and communal breeding and needed large numbers for optimum breeding conditions. It was impossible to reestablish the species with just a few captive birds, and the small captive flocks weakened and died. Since no accurate data were recorded, it is only possible to give estimates on the size and population of these nesting areas. Each site may have covered many thousands of acres and the birds were so congested in these areas that hundreds of nests could be counted in each tree. One large nesting area in Wisconsin was reported as covering 850 square miles, and the number of birds nesting there was estimated to be around 136,000,000. Their technique of survival had been based on mass tactics.

There was safety in large flocks which often numbered hundreds of thousands of birds. When a flock of this huge a size established itself in an area, the number of local animal predators (such as wolves, foxes, weasels, and hawks) was so small compared to the total number of birds that little damage would be inflicted on the flock as a whole. This colonial way of life and communal breeding became very dangerous when humans began to hunt the pigeons. When the passenger pigeons were massed together, especially at a huge nesting site, it was easy for people to slaughter them in such great numbers that there were not enough birds left to successfully reproduce the species.[10] As the flocks dwindled in size with resulting breakdown of social facilitation, it was doomed to disappear.[11]

The extinction of the passenger pigeon aroused public interest in the conservation movement and resulted in new laws and practices which have prevented many other species from going extinct.[citation needed]

Methods of killing

Alcohol-soaked grain intoxicated the birds and made them easier to kill. Smoky fires were set to nesting trees to drive them from their nests.[12]

One method of killing was to blind a single bird by sewing its eyes shut using a needle and thread. This bird's feet would be attached to a circular stool at the end of a stick that could be raised five or six feet in the air, then dropped back to the ground. As the bird attempted to land, it would flutter its wings, thus attracting the attention of other birds flying overhead. When the flock landed near this decoy bird, nets would trap the birds and the hunters would crush their heads between their thumb and forefinger. This has been claimed as the origin of the term stool pigeon,[13] though this etymology is disputed.[14]

One of the last large nestings of passenger pigeons was at Petoskey, Michigan, in 1878. Here 50,000 birds were killed each day and the hunt continued for nearly five months. When the adult birds that survived the slaughter attempted second nestings at new sites, they were located by the professional hunters and killed before they had a chance to raise any young. In 1896, the final flock of 250,000 were killed by the hunters knowing that it was the last flock of that size.

Conservationists were ineffective in stopping the slaughter. A bill was passed in the Michigan legislature making it illegal to net pigeons within two miles of a nesting area, but the law was weakly enforced. By the mid 1890s, the passenger pigeon had almost completely disappeared. In 1897, a bill was introduced in the Michigan legislature asking for a ten-year closed season on passenger pigeons. This was a futile gesture. This was a highly gregarious species—the flock could initiate courtship and reproduction only when they were gathered in large numbers; it was realized only too late that smaller groups of passenger pigeons could not breed successfully, and the surviving numbers proved too few to re-establish the species.[3] Attempts at breeding among the captive population also failed for the same reasons.

Last wild survivors

The last fully authenticated record of a wild bird was near Sargents, Pike County, Ohio, on March 22, 1900,[3][15] although many unconfirmed sightings were reported in the first decade of the 20th century.[16][17][18] From 1909 to 1912, a reward was offered for a living specimen[19]— no specimens were found. However, unconfirmed sightings continued up to about 1930.[20]

Reports of passenger pigeon sightings kept coming in from Arkansas and Louisiana, in groups of tens and twenties, until the first decade of the 20th century.

The naturalist Charles Dury, of Cincinnati, Ohio, wrote in September 1910:

One foggy day in October 1884, at 5 a.m. I looked out of my bedroom window, and as I looked six wild pigeons flew down and perched on the dead branches of a tall poplar tree that stood about one hundred feet away. As I gazed at them in delight, feeling as though old friends had come back, they quickly darted away and disappeared in the fog, the last I ever saw of any of these birds in this vicinity.[21]

Martha

On September 1, 1914, Martha, the last known passenger pigeon, died in the Cincinnati Zoo, Cincinnati, Ohio. Her body was frozen into a block of ice and sent to the Smithsonian Institution, where it was skinned and mounted. Currently, Martha (named after Martha Washington) is in the museum's archived collection, and not on display.[22] A memorial statue of Martha stands on the grounds of the Cincinnati Zoo.

Popular culture

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (January 2010) |

The dramatic story of the passenger pigeon has taken a strong hold on popular imagination.

- Aldo Leopold wrote about the loss of the pigeon in his seminal 1949 book A Sand County Almanac. The extract is called "On A Monument to the Pigeon".

- The musician John Herald wrote a song about Martha, "Martha (Last of the Passenger Pigeons)".

- The April 27, 1948 episode of the Fibber McGee and Molly radio program is titled "The Passenger Pigeon Trap", in which McGee claims to have seen a passenger pigeon (he insists that the bird is "stinct") and plans to trap it in order to sell it to the highest bidder. It turns out to be nothing more than a Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) sitting on top of a bus, which in McGee's mind makes the pigeon a passenger. Hence, "passenger pigeon". This episode has two inaccuracies regarding the last Passenger Pigeon. According to the character known as "Mr. Old Timer", the name of the last pigeon is incorrectly named Millie, not Martha, and died on July 4, 1914, not September 1, 1914.

- In "The Man Trap", the premiere episode of Star Trek, Professor Crater likens the near-extinction of the inhabitants of planet M113 to the demise of the passenger pigeon.

- A one-shot episode of The Bloodhound Gang, entitled "The Case of the Dead Man's Pigeon", had the deceased Mr. Fowler allegedly cutting off his living relative and leaving his fortune to a society dedicated to preserving the American Passenger Pigeon, according to a revised will of his. But Vicki learns and points out that the American Passenger Pigeon was officially extinct in 1914, thus making Mr. Fowler's revised final will a fake. It was actually forged by the crooked lawyer who reads the will, Mr. Pettifog, as a swindle, and the fact of the American Passenger Pigeon's extinction reveals Mr. Pettifog to be a phony.

- Stephen King makes a number of references to the passenger pigeon in the 2005 novel Cell. He uses the pigeon as an allegory to the new human hive mind that develops after the pulse hits the United States.

- In the 1999 movie by Jim Jarmusch, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, Louie (John Tormey) identifies the bird owned by the titular character as a "carrier pigeon". He is corrected by an elderly mafioso who shouts, "Passenger pigeon! Passenger pigeon! They've been extinct since 1914!" (The bird was in fact one of the homing pigeons Ghost Dog used to transport - "carry" - notes, which explains Louie's misidentification).

- Ectopistes migratorius is the second chapter of the novel Havana Glam (2001) by Wu Ming 5. The reappearance of the pigeons in 1944 is the first signal of the arrival of time travelers from the 21st century USA.

- A description of the passage of a flock of passenger pigeons, and the killing of large numbers of the birds, is given in James Fenimore Cooper's novel The Pioneers. Although this was published in 1823, Natty Bumppo expresses outrage at people's "wastey ways" and concern about the possible future extinction of the bird.

- The Australian poet Judith Wright wrote a poem called "Lament For Passenger Pigeons."

- The Indie-Rock band Paint By Numbers wrote a song called "Martha, Sweet Martha" in memory of the last passenger pigeon.

- The alt-country duo The Handsome Family have a song called "Passenger Pigeons" featuring on their 2001 album Twilight

- Large passenger pigeons flocks appear in two of Howard Waldrop's works: "...the World, as we Know't" and Them Bones.

- Featured in the non-fiction book "The World Without Us" by Alan Weisman

- The character, Iggy, in the extinction musical story, Rockford's Rock Opera, is the world's last Passenger Pigeon.

- In Diana Gabaldon's book The Fiery Cross, set in 18th century North Carolina, a huge migration of Passenger Pigeons are hunted by a tribe of American Indians as they pass by.

- Harry Turtledove's alternate history novel How Few Remain includes a scene in which several characters eat passenger pigeon for dinner, across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. In a later book in the series, passenger pigeons are also mentioned. In both cases, their decreased numbers are remarked upon.

- In Steven Gould's novel Wildside the protagonists discover a portal to a parallel universe where no humans have ever been (at least not in the otherwise duplicate of North America). There have been no human caused extinctions and Pleistocene megafauna still roam the landscape. In order to finance its exploration and their planned gold prospecting in the Rocky Mountains, they anonymously ship a half-dozen female passenger pigeons each to four zoos and nature groups. They then offer to sell each facility one male passenger pigeon for $50,000. While there is some grumbling, the zoos all pay up and the young adults now have their operating capital.

In art

John James Audubon illustrates the Passenger Pigeon in Birds of America, Second Edition (published, London 1827-38) as Plate 62 where a pair of birds (male and female) are shown. The image was engraved and colored by Robert Havell's, London workshops. The original watercolor by Audubon was purchased by the New York History Society where it remains to this day (January 2009).

Place names

Across North America, place names refer to the former abundance of the passenger pigeon. Examples include:

- Crockford Pigeon Mountain, Georgia

- Mimico, a neighborhood of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The name means "The Place of the Passenger Pigeons" in the language of the Mississauga Indians.

- Pigeon Forge, Tennessee

- Pigeon Lakes: Minnesota, Wisconsin, Alberta, Ontario

- Pigeon Point: Minnesota

- Pigeon Rivers in: Minnesota-Ontario, North Carolina/Tennessee, Michigan (four), and Wisconsin

- Pigeon Roost State Historic Site, Indiana

- Pigeontown, Pennsylvania, now known as Blue Bell

- White Pigeon, Michigan.

- Pigeon Hill, Marietta Georgia.

- Ile-Aux-Tourtes, an island west of Montreal Island on the Trans-Canada Highway-Autoroute 40. It means, Passenger Pigeon Island (in French-Canadian).

- Pigeon, Pennsylvania

- Omemee, North Dakota (the town's name is a corruption of the Chippewa word 'omiimii')

Coextinction

An often-cited example of coextinction is that of the passenger pigeon and its parasitic louse Columbicola extinctus and Campanulotes defectus. Recently,[23][24] C. extinctus was rediscovered on the Band-tailed Pigeon, and C. defectus was found to be a likely case of misidentification of the existing Campanulotes flavus.

Closest species

One of the most closely related species to Passenger Pigeon seems to be the Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura),[25][26][27] which is one of the most abundant and widespread of all North American birds. Mourning Doves are smaller and less brightly colored than Passenger Pigeons. For this reason, there are many discussions about the principal possibility of using Mourning Dove as a good choice for cloning the Passenger Pigeon in the future.[28]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ "Three Hundred Dollars Reward; Will Be Paid for a Nesting Pair of Wild Pigeons, a Bird So Common in the United States Fifty Years Ago That Flocks in the Migratory Period Frequently Partially Obscured the Sun from View. How America Has Lost Birds of Rare Value and How Science Plans to Save Those That Are Left". New York Times. January 16, 1910 Sunday.

Unless the State and Federal Governments come to the rescue of American game, plumed, and song birds, the not distant future will witness the practical extinction of some of the most beautiful and valuable species. Already the snowy heron, that once swarmed in immense droves over the United States, is gone, a victim of the greed and cruelty of milliners whose "creations" its beautiful nuptial feathers have gone to adorn.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ask

- ^ a b c d e Smithsonian Institution; it is believed that this species once constituted 25 to 40 per cent of the total bird population of the United States. It is estimated that there were 3 billion to 5 billion passenger pigeons at the time Europeans discovered America.

- ^

"Prior to 1492, this was a rare species."

Mann, Charles C. (2005). "The Artificial Wilderness". 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 315–8. ISBN 1-4000-4006-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:IUCN2006 Database entry includes justification for why this species is listed as extinct

- ^ http://www.sciencenetlinks.com/pdfs/pigeons1_actsheet.pdf

- ^ Atkinson, George E. (1907). "16, The Pigeon in Manitoba". In W B Mershon (ed.). The Passenger Pigeon. New York: The Outing Publishing Co. p. 188.

- ^ http://www.ulala.org/P_Pigeon/Audubon_Pigeon.html "On The Passenger Pigeon", Birds of America, John James Audubon

- ^ Hornaday, W.T. 1913: Our Vanishing Wild Life. Its Extermination and Preservation

- ^ "The Passenger Pigeon", Encyclopedia Smithsonian, Prepared by the Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History in cooperation with the Public Inquiry Mail Service, Smithsonian Institution

- ^ Passenger Pigeon, The Extinction Website

- ^ Iowa Department of Natural Resources

- ^ Stool Pigeon

- ^ World Wide Words: Stool pigeon

- ^ The date of March 24 was given in the report by Henniger, but there are many discrepancies with the actual circumstances, meaning he was writing from hearsay. A curator's note that apparently derives from an old specimen label has March 22.

- ^ Passenger Pigeons in Alabama

- ^ Life of birds – Was Martha the last “Pigean de passage”?

- ^ A History Of The Passenger Pigeon In Missouri

- ^ The New York Times; April 4, 1910, Monday; Reward for Wild Pigeons. Ornithologists Offer $3,000 for the Discovery of Their Nests.

- ^ Passenger Pigeon

- ^

Dury, Charles (1910). "The Passenger Pigeon". Journal of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History. 21: 52–56.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Encyclopedia Smithsonian". Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ Clayton, D. H., and R. D. Price. 1999. Taxonomy of New World Columbicola (Phthiraptera: Philopteridae) from the Columbiformes (Aves), with descriptions of five new species. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 92:675–685.

- ^ Price, R.D., D. H. Clayton, R. J. Adams, J. (2000) Pigeon lice down under: Taxonomy of Australian Campanulotes (Phthiraptera: Philopteridae), with a description of C. durdeni n.sp. Parasitol. 86(5), p 948-950. American Society of Parasitologists. Online pdf

- ^ Save The Doves - Facts

- ^ The Biology and natural history of the Mourning Dove

- ^ The Mourning Dove in Missouri

- ^ Cloning Extinct Species, Part II

Further reading

- Weidensaul, Scott (1994). Mountains of the Heart: A Natural History of the Appalachians. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing. ISBN 1-55591-143-9.

- Eckert, Allan W. (1965). The Silent Sky: The Incredible Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon. Lincoln NE: IUniverse.com. ISBN 0-595-08963-1.

- French, John C., The Passenger Pigeon in Pennsylvania (Altoona, Pa.: Altoona Tribune Co., 1919).

- Mershon, W. B., ed. (1907)

The Passenger Pigeon New York: Outing Press

The Passenger Pigeon New York: Outing Press - Schorger, A.W. 1955. The Passenger Pigeon: Its Natural History and Extinction. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI. Reprinted in paperback, 2004, by Blackburn Press. ISBN 1-930665-96-2. 424 pp.

- Price, Jennifer 2000. Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America. Basic Books. ISBN 0465024866. 325 pp.

External links

- Songbird Foundation: Passenger Pigeon

- The Extinction Website - Passenger Pigeon

- Passenger Pigeon Society

- The Demise of the Passenger Pigeon (as broadcast on NPR's Day to Day)

- 3D view of specimens RMNH 110.048, RMNH 15707, RMNH 110.090, RMNH 110.091, RMNH 110.092, RMNH 110.093, RMNH 110.089, RMNH 110.085, RMNH 110.086, RMNH 110.087 and RMNH 110.088 at Naturalis, Leiden (requires QuickTime browser plugin).