Mitral regurgitation

| Mitral regurgitation | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Mitral regurgitation (MR), mitral insufficiency or mitral incompetence is a disorder of the heart in which the mitral valve does not close properly when the heart pumps out blood. It is the abnormal leaking of blood from the left ventricle, through the mitral valve, and into the left atrium, when the left ventricle contracts, i.e. there is regurgitation of blood back into the left atrium.[1] MR is the most common form of valvular heart disease.[2]

Incidence

It has an incidence of approximately 2% of the population, affecting males and females equally.[3] It is one of the two most common valvular heart disease in the elderly.[4]

Etiology

The mitral valve is composed of two valve leaflets, the mitral valve annulus (which forms a ring around the valve leaflets), the papillary muscles (which tether the valve leaflets to the left ventricle, preventing them from prolapsing into the left atrium), and the chordae tendineae (which connect the valve leaflets to the papillary muscles). A dysfunction of any of these portions of the mitral valve apparatus can cause mitral regurgitation. The most common cause of mitral regurgitation is mitral valve prolapse (MVP), which in turn is caused by myxomatous degeneration.[5] The most common cause of primary mitral regurgitation in the United States (causing about 50% of primary mitral regurgitation) is myxomatous degeneration of the valve. Myxomatous degeneration of the mitral valve is more common in females, and is more common in advancing age. This causes a stretching out of the leaflets of the valve and the chordae tendineae. The elongation of the valve leaflets and the chordae tendineae prevent the valve leaflets from fully coapting when the valve is closed, causing the valve leaflets to prolapse into the left atrium, thereby causing mitral regurgitation.

Ischemic heart disease causes mitral regurgitation by the combination of ischemic dysfunction of the papillary muscles, and the dilatation of the left ventricle that is present in ischemic heart disease, with the subsequent displacement of the papillary muscles and the dilatation of the mitral valve annulus.

Rheumatic fever and Marfan's syndrome are other typical causes of mitral regurgitation.[6]

Secondary mitral regurgitation is due to the dilatation of the left ventricle, causing stretching of the mitral valve annulus and displacement of the papillary muscles. This dilatation of the left ventricle can be due to any cause of dilated cardiomyopathy, including aortic insufficiency, nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy. It is also called functional mitral regurgitation, because the papillary muscles, chordae, and valve leaflets are usually normal.[7]

Acute mitral regurgitation is most often caused by endocarditis, mainly S. aureus.[6] Papillary muscle rupture or dysfunction,[6] including mitral valve prolapse,[8] are also common causes in acute cases.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of mitral regurgitation can be broken into three phases of the disease process: the acute phase, the chronic compensated phase, and the chronic decompensated phase.[9]

Acute phase

Acute mitral regurgitation (as may occur due to the sudden rupture of a chorda tendinea or papillary muscle) causes a sudden volume overload of both the left atrium and the left ventricle. The left ventricle develops volume overload because with every contraction it now has to pump out not only the volume of blood that goes into the aorta (the forward cardiac output or forward stroke volume), but also the blood that regurgitates into the left atrium (the regurgitant volume). The combination of the forward stroke volume and the regurgitant volume is known as the total stroke volume of the left ventricle.

In the acute setting, the stroke volume of the left ventricle is increased (increased ejection fraction), this happens because of more complete emptying of heart. However, as it progresses the LV volume increases and the contractile function deteriorates and thus leading to dysfunctional LV and a decrease in ejection fraction.[10] The increase in stroke volume is explained by the Frank–Starling mechanism, in which increased ventricular pre-load stretches the myocardium such that contractions are more forceful.

The regurgitant volume causes a volume overload and a pressure overload of the left atrium. The increased pressures in the left atrium inhibit drainage of blood from the lungs via the pulmonary veins. This causes pulmonary congestion.

Chronic phase

Compensated

If the mitral regurgitation develops slowly over months to years or if the acute phase can be managed with medical therapy, the individual will enter the chronic compensated phase of the disease. In this phase, the left ventricle develops eccentric hypertrophy in order to better manage the larger than normal stroke volume. The eccentric hypertrophy and the increased diastolic volume combine to increase the stroke volume (to levels well above normal) so that the forward stroke volume (forward cardiac output) approaches the normal levels.

In the left atrium, the volume overload causes enlargement of the chamber of the left atrium, allowing the filling pressure in the left atrium to decrease. This improves the drainage from the pulmonary veins, and signs and symptoms of pulmonary congestion will decrease.

These changes in the left ventricle and left atrium improve the low forward cardiac output state and the pulmonary congestion that occur in the acute phase of the disease. Individuals in the chronic compensated phase may be asymptomatic and have normal exercise tolerances.

Decompensated

An individual may be in the compensated phase of mitral regurgitation for years, but will eventually develop left ventricular dysfunction, the hallmark for the chronic decompensated phase of mitral regurgitation. It is currently unclear what causes an individual to enter the decompensated phase of this disease. However, the decompensated phase is characterized by calcium overload within the cardiac myocytes.

In this phase, the ventricular myocardium is no longer able to contract adequately to compensate for the volume overload of mitral regurgitation, and the stroke volume of the left ventricle will decrease. The decreased stroke volume causes a decreased forward cardiac output and an increase in the end-systolic volume. The increased end-systolic volume translates to increased filling pressures of the left ventricle and increased pulmonary venous congestion. The individual may again have symptoms of congestive heart failure.

The left ventricle begins to dilate during this phase. This causes a dilatation of the mitral valve annulus, which may worsen the degree of mitral regurgitation. The dilated left ventricle causes an increase in the wall stress of the cardiac chamber as well.

While the ejection fraction is less in the chronic decompensated phase than in the acute phase or the chronic compensated phase of mitral regurgitation, it may still be in the normal range (i.e.: > 50 percent), and may not decrease until late in the disease course. A decreased ejection fraction in an individual with mitral regurgitation and no other cardiac abnormality should alert the physician that the disease may be in its decompensated phase.

Effect of diastolic blood pressure

A change in the severity of mitral regurgitation may be associated with a change in diastolic pressure. In a study of people with heart valve regurgitation that compared measurements 2 weeks apart for each person, there was an increased severity of mitral regurgitation when diastolic blood pressure increased, whereas when diastolic blood pressure decreased, there was a decreased severity.[11]

Symptoms and signs

The symptoms associated with mitral regurgitation are dependent on which phase of the disease process the individual is in. Individuals with acute mitral regurgitation will have the signs and symptoms of decompensated congestive heart failure (i.e. shortness of breath, pulmonary edema, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea[6]), as well as symptoms suggestive of a low cardiac output state (i.e. decreased exercise tolerance). Palpitations are also common.[6] Cardiovascular collapse with shock (cardiogenic shock) may be seen in individuals with acute mitral regurgitation due to papillary muscle rupture or rupture of a chorda tendinae.

Individuals with chronic compensated mitral regurgitation may be asymptomatic, with a normal exercise tolerance and no evidence of heart failure. These individuals may be sensitive to small shifts in their intravascular volume status, and are prone to develop volume overload (congestive heart failure).

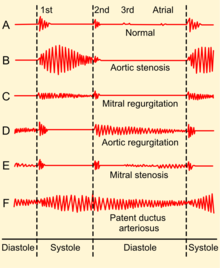

Findings on clinical examination depend on the severity and duration of mitral regurgitation. The mitral component of the first heart sound is usually soft and with a laterally displaced apex beat,[6] often with heave.[8] The first heart sound is followed by a high-pitched holosystolic murmur at the apex, radiating to the back or clavicular area.[6] Its duration is, as the name suggests, the whole of systole. The loudness of the murmur does not correlate well with the severity of regurgitation. It may be followed by a loud, palpable P2,[6] heard best when lying on the left side.[8] A third heart sound is commonly heard.[6]

Commonly, atrial fibrillation is found.[6]

In acute cases, the murmur and tachycardia may be only distinctive signs.[8]

Patients with mitral valve prolapse often have a mid-to-late systolic click and a late systolic murmur.

Diagnostic studies

There are many diagnostic tests that have abnormal results in the presence of mitral regurgitation. These tests suggest the diagnosis of mitral regurgitation and may indicate to the physician that further testing is warranted. For instance, the electrocardiogram (ECG) in long standing mitral regurgitation may show evidence of left atrial enlargement and left ventricular hypertrophy. Atrial fibrillation may also be noted on the ECG in individuals with chronic mitral regurgitation. The ECG may not show any of these finding in the setting of acute mitral regurgitation.

| Acute | Chronic | |

|---|---|---|

| Electrocardiogram | Normal | P mitrale, Atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Heart size | Normal | Cardiomegaly, left atrial enlargement |

| Systolic murmur | Heard at the base, radiates to the neck, spine, or top of head | Heard at the apex, radiates to the axilla |

| Apical thrill | May be absent | Present |

| Jugular venous distension | Present | Absent |

The quantification of mitral regurgitation usually employs imaging studies such as echocardiography or magnetic resonance angiography of the heart.

Chest x-ray

The chest x-ray in individuals with chronic mitral regurgitation is characterized by enlargement of the left atrium and the left ventricle.[6] The pulmonary vascular markings are typically normal, since pulmonary venous pressures are usually not significantly elevated.

Echocardiography

The echocardiogram is commonly used to confirm the diagnosis of mitral regurgitation. Color doppler flow on the transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) will reveal a jet of blood flowing from the left ventricle into the left atrium during ventricular systole. Also, it may detect a dilated left atrium and ventricle and decreased left ventricular function.[6]

Because of the inability in getting accurate images of the left atrium and the pulmonary veins on the transthoracic echocardiogram, a transesophageal echocardiogram may be necessary to determine the severity of the mitral regurgitation in some cases.

Factors that suggest severe mitral regurgitation on echocardiography include systolic reversal of flow in the pulmonary veins and filling of the entire left atrial cavity by the regurgitant jet of MR.

Electrocardiography

P mitrale is broad, notched P waves in several or many leads with a prominent late negative component to the P wave in lead V1, and may be seen in mitral regurgitation, but also in mitral stenosis, and, potentially, any cause of overload of the left atrium.[12] Thus, P-sinistrocardiale may be a more appropriate term.[12]

Quantification of mitral regurgitation

The degree of severity of mitral regurgitation can be quantified by the regurgitant fraction, which is the percentage of the left ventricular stroke volume that regurgitates into the left atrium.

- regurgitant fraction =

where Vmitral and Vaortic are respectively the volumes of blood that flow forward through the mitral valve and aortic valve during a cardiac cycle. Methods that have been used to assess the regurgitant fraction in mitral regurgitation include echocardiography, cardiac catheterization, fast CT scan, and cardiac MRI.

The echocardiographic technique to measure the regurgitant fraction is to determine the forward flow through the mitral valve (from the left atrium to the left ventricle) during ventricular diastole, and comparing it with the flow out of the left ventricle through the aortic valve in ventricular systole. This method assumes that the aortic valve does not suffer from aortic insufficiency.

Another way to quantify the degree of mitral regurgitation is to determine the area of the regurgitant flow at the level of the valve. This is known as the regurgitant orifice area, and correlates with the size of the defect in the mitral valve. One particular echocardiographic technique used to measure the orifice area is measurement of the proximal isovelocity surface area (PISA). The flaw of using PISA to determine the mitral valve regurgitant orifice area is that it measures the flow at one moment in time in the cardiac cycle, which may not reflect the average performance of the regurgitant jet.

| Degree of mitral regurgitation | Regurgitant fraction | Regurgitant Orifice area |

|---|---|---|

| Mild mitral regurgitation | < 20 percent | |

| Moderate mitral regurgitation | 20 - 40 percent | |

| Moderate to severe mitral regurgitation | 40 - 60 percent | |

| Severe mitral regurgitation | > 60 percent | > 0.3 cm2 |

Treatment

The treatment of mitral regurgitation depends on the acuteness of the disease and whether there are associated signs of hemodynamic compromise.

In acute mitral regurgitation secondary to a mechanical defect in the heart (i.e.: rupture of a papillary muscle or chordae tendineae), the treatment of choice is urgent mitral valve replacement. If the patient is hypotensive prior to the surgical procedure, an intra-aortic balloon pump may be placed in order to improve perfusion of the organs and to decrease the degree of mitral regurgitation.[6]

If the individual with acute mitral regurgitation is normotensive, vasodilators may be of use to decrease the afterload seen by the left ventricle and thereby decrease the regurgitant fraction. The vasodilator most commonly used is nitroprusside.

Individuals with chronic mitral regurgitation can be treated with vasodilators as well to decrease afterload.[6] In the chronic state, the most commonly used agents are ACE inhibitors and hydralazine. Studies have shown that the use of ACE inhibitors and hydralazine can delay surgical treatment of mitral regurgitation.[13][14] The current guidelines for treatment of mitral regurgitation limit the use of vasodilators to individuals with hypertension, however. Any hypertension is treated aggressively,[8] e.g. by diuretics and a low sodium diet.[6] In both hypertensive and normotensive cases, digoxin and antiarrhythmics are also indicated.[6][8] Also, chronic anticoagulation is given where there is concomitant mitral valve prolapse[8] or atrial fibrillation.[6]

There are two surgical options for the treatment of mitral regurgitation: mitral valve replacement and mitral valve repair.[6] In the double orifice technique for mitral valve repair, the opening of the mitral valve is sewn closed in the middle, leaving the two ends still able to open. This ensures that the mitral valve closes when the left ventricle pumps blood, yet allows the mitral valve to open at the two ends to fill the left ventricle with blood before it pumps. The same idea can be used with a minimally-invasive catheter technique which installs a clip to hold the middle of the mitral valve closed.[15][16]

There is also a non-surgical option for the treatment of mitral regurgitation. Mitral-valve repair can be accomplished with an investigational procedure that involves the percutaeneous implantation of a clip that grips and approximates the edges of the mitral leaflets at the origin of the regurgitant jet. Thought it is less effective at reducing mitral regurgitation than conventional surgery, the procedure is marked by superior safety and similar improvements.[17]

Indication for surgery

Indications for surgery for chronic mitral regurgitation include signs of left ventricular dysfunction. These include an ejection fraction of less than 60 percent and a left ventricular end systolic dimension (LVESD) of more than 45 mm.

| Symptoms | LV EF | LVESD |

|---|---|---|

| NYHA II - IV | > 60 percent | < 45 mm |

| Asymptomatic or symptomatic | 50 - 60 percent | ≥ 45 mm |

| Asymptomatic or symptomatic | < 50 percent and ≥ 45 mm | |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure ≥ 50 mmHg | ||

See also

- Mitral valve

- Left ventricle

- Left atrium

- Systole (medicine)

- Diastole

- Cardiac output

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Cardiomyopathy

References

- ^ Mitral valve regurgitation at Mount Sinai Hospital

- ^ Weinrauch, LA (2008-05-12). "Mitral regurgitation - chronic". Medline Plus Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ The Cleveland Clinic Center for Continuing Education > Mitral Valve Disease: Stenosis and Regurgitation Authors: Ronan J. Curtin and Brian P. Griffin. Retrieved September 2010

- ^ Valvular heart disease in elderly adults Authors: Dania Mohty, Maurice Enriquez-Sarano. Section Editors:Catherine M Otto, Kenneth E Schmader. Deputy Editor: Susan B Yeon. This topic last updated: April 20, 2007. Last literature review version 18.2: May 2010

- ^ Kulick, Daniel. "Mitral Valve Prolapse (MVP)". MedicineNet.com. MedicineNet, Inc. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-7153-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Chapter 1: Diseases of the Cardiovascular system > Section: Valvular Heart Disease - ^ Functional mitral regurgitation By William H Gaasch, MD. Retrieved on Jul 8, 2010

- ^ a b c d e f g VOC=VITIUM ORGANICUM CORDIS, a compendium of the Department of Cardiology at Uppsala Academic Hospital. By Per Kvidal September 1999, with revision by Erik Björklund May 2008

- ^ Di Sandro, D (2009-06-08). "Mitral Regurgitation". eMedicine. Medscape. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- ^ Harrison's Internal Medicine 17th edition

- ^ Gottdiener JS, Panza JA, St John Sutton M, Bannon P, Kushner H, Weissman NJ (July 2002). "Testing the test: The reliability of echocardiography in the sequential assessment of valvular regurgitation". American Heart Journal. 144 (1): 115–21. doi:10.1067/mhj.2002.123139. PMID 12094197. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b medilexicon.com < P mitrale Citing. Stedman's Medical Dictionary. Copyright 2006

- ^ Greenberg BH, Massie BM, Brundage BH, Botvinick EH, Parmley WW, Chatterjee K (1978). "Beneficial effects of hydralazine in severe mitral regurgitation". Circulation. 58 (2): 273–9. PMID 668075.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hoit BD (1991). "Medical treatment of valvular heart disease". Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 6 (2): 207–11. doi:10.1097/00001573-199104000-00005. PMID 10149580.

- ^ Tirrell, Meg (2010-03-14). "Abbott MitraClip Offers Safe Alternative to Open-Heart Surgery". Bloomberg Business Week. Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Garg P, Walton AS (2008). "The new world of cardiac interventions: a brief review of the recent advances in non-coronary percutaneous interventions". Heart Lung Circ. 17 (3): 186–99. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2007.10.019. PMID 18262841.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Feldman M.D., Ted (14 April 2011). "Percutaneous Repair or Surgery for Mitral Regurgitation". New England Journal of Medicine. 364: 1395–1406. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009355.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bonow R; et al. (1998). "ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association. Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease)". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 32 (5): 1486–588. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00454-9. PMID 9809971.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)

External links

- Echocardiographic features of mitral regurgitation at Wikiecho

- Mitral Valve Repair at The Mount Sinai Hospital

- Mitral Regurgitation information from Seattle Children's Hospital Heart Center

- NEW Investigational Treatment in the EVEREST II Clinical Research Study - Percutaneous Mitral Repair

- Mitral Valve Auscultation