Squat (exercise)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

In strength training, the squat is a compound, full body exercise that trains primarily the muscles of the thighs, hips and buttocks, hamstrings, as well as strengthening the bones, ligaments and insertion of the tendons throughout the lower body. Squats are considered a vital exercise for increasing the strength and size of the legs and buttocks, as well as developing core strength. Isometrically, the lower back, the upper back, the abdominals, the trunk muscles, the costal muscles, and the shoulders and arms are all essential to the exercise and thus are trained when squatting with proper form.[1]

Squats are a competitive lift in powerlifting.

Muscles engaged

- Primary Muscles

- Erector Spinae, Gluteus Maximus (glutes), Quadriceps (quads), Hamstrings[2]

- Secondary Muscles(Synergists/Stabilizers)

- Transverse Abdominus, Gluteus medius/minimus (Abductors), Adductors, Soleus, Gastrocnemius[2]

Form

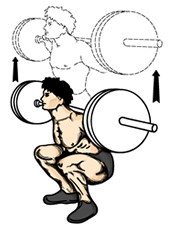

The movement begins from a standing position. Weights are often used, either in the hand or as a bar braced across the trapezius muscle or rear deltoid muscle in the upper back.[3] The movement is initiated by moving the hips back and bending the knees and hips to lower the torso and accompanying weight, then returning to the upright position. The squat can continue to a number of depths, but a correct squat should be at least to parallel. Squatting below parallel qualifies a squat as deep while squatting above it qualifies as shallow.[3] Correctly performed full squats (as demonstrated by olympic lifters in training and nearly all competitive lifters) are much safer on the knees and remove pressure from the lower lumbar region.

As the body descends, the hips and knees undergo flexion, the ankle dorsiflexes and muscles around the joint contract eccentrically, reaching maximal contraction at the bottom of the movement while slowing and reversing descent. The muscles around the hips provide the power out of the bottom. If the knees slide forward or cave in then tension is taken from the hamsrings, hindering power on the ascent. Returning to vertical contracts the muscles concentrically, and the hips and knees undergo extension while the ankle plantarflexes.[3]

Two common errors include descending too rapidly and flexing the torso too far forward. Rapid descent risks being unable to complete the lift or causing injury. This occurs when the descent causes the squatting muscles to relax and tightness at the bottom is lost as a result. Over-flexing the torso greatly increases the forces exerted on the lower back, risking a spinal disc herniation.[3]

Another error where health of the knee joint is concerned is when the knee is not aligned with the direction of the toes. If the knee is not tracking over the toes during the movement this results in twisting/shearing of the joint and unwanted torque affecting the ligaments which can soon result in injury. The knee should always follow the toe. Have your toes slightly pointed out in order to track the knee properly.

Equipment

Various types of equipment can be used to assist with squats. A power cage can be used to reduce risk of injury and eliminate the need for a spotting partner. Bar path should be dictated by stabilizing muscular and skeletal anatomy and not by the use of upright fixed supports. The Smith machine also removes use of the hips from the movement which turns the exercise into something resembling a leg press instead of a true squat.[4] Other equipment used can include a weight lifting belt to support the torso and boards to wedge beneath the ankles to improve stability and allow a deeper squat (some shoes also have wooden wedges built into the sole to mimic this). Heel wedges and related equipment are discouraged by some as they are thought to worsen form over the long term.[5] The barbell can also be cushioned with a special padded sleeve, used if the weight becomes uncomfortable for the lifter.

World records

- The heaviest unequipped, drug tested squat is 430 kg (948 lbs), held by Joe Uttoe [6]

- The heaviest unequipped squat record (no squat suit) is 453 kg (1000 lbs), held by Robert Wilkerson (USA).[citation needed]

- The IPF record (singly ply squat suit only, drug tested) is 457.5 kg (1008 lbs), held by Shane Hamman (USA).[citation needed]

- The record with unlimited equipment is 571.5 kg (1260 lbs) held by Donnie Thompson.[7]

- The world record for sumo squats (with no weights) performed in one hour is 5,135, held by Dr. Thienna Ho (Vietnam).[8]

- The heaviest unequipped front squat, is 350 kg (770 lbs), held by Warrick Brant (AUS).[citation needed]

Variants

The squat has a number of variants, some of which can be combined (e.g. a dumbbell split squat):

- Back squat - the bar is held on the back of the body at the base of the neck or lower across the upper back. In powerlifting the barbell is often held in a lower position in order to create a lever advantage, while in weightlifting it is often held in a higher position which produces a posture closer to that of the Clean and Jerk. These variations are called low bar and high bar, respectively.

- Front squat - the weight (usually a barbell) is held in front of the body across the clavicles and deltoids in either a clean grip, as is used in weightlifting, or with the arms crossed and hands placed on top of the barbell.

- Overhead squat - a barbell is held overhead in a wide-arm snatch grip; however, it is also possible to use a closer grip if flexibility allows.

- Zercher squat - the bar is held in the crooks of the arms, on the inside of the elbow.

- Hack squat - a barbell is held in the hands just behind the legs; invented by early 1900s professional wrestler Georg Hackenschmidt.

- Sissy squat - a dumbbell is held behind the legs while the heels are lifted off the ground and the torso remains flat while the lifter leans backwards; sometimes done with a plate held on the chest and one arm holding onto a chair or beam for support.

- Split squat - an assisted one-legged squat where the non-lifting leg is rested on the ground a few 'steps' behind the lifter, as if it were a static lunge.

- Bulgarian squat is performed much like a split squat, but the foot of the non-lifting leg is rested on a knee-high platform behind the lifter.

- Hindu squat - is done without weight where the heels are raised and body weight is placed on the toes; the knees track far past the toes.

- Jump squat - a plyometrics exercise where the squatter jumps off the floor at the top of the lift.

- Bodyweight squat - done with no weight or barbell, often at higher repetitions than other variants.

- Box squat - at the bottom of the motion the squatter will sit down on a bench or other type of support then rise again. The box squat is commonly utilized by power lifters to train the squat. Pausing on the box creates additional stimulus in the hips and glutes. Some people believe this form of isometric training allows for greater gains in the squat opposed compared to a traditional Olympic style squat, while others contend that the increased spinal loading creates more opportunity for injury.

- Pistol - a bodyweight squat done on one leg to full depth, while the other leg is extended off the floor. Sometimes dumbbells or kettlebells are added for resistance. (aka single leg squat).

- Belt squat - is an exercise performed the same as other squat variations except the weight is attached to a hip belt i.e. a dip belt

- Face the wall squat - performed with or without weights. It is primarily to strength the vertebrae tissues. In the Chinese variant (面壁蹲墙) weights are not used. Toes, knees and nose line up almost touching the wall. Advanced forms include shoeless, wrists crossed behind the back, and fists in front of forehead, all performed with toes and knees closed and touching the wall.

Injury considerations

Although the squat has long been a basic element of weight training, it has in recent years been the subject of considerable controversy. Some trainers allege that squats are associated with injuries to the lumbar spine and knees.[9] As a result, many trainers suggest that the standard olympic bar squat be modified in various ways, including the box squat and the Zercher squat. Others, however, continue to advocate the squat as one of the best exercises for building muscle and strength. Some coaches maintain that the common "half-squat" (parallel) and "quarter-squat" (above parallel) are both less effective and more likely to cause injury than a full squat (below parallel).

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Rippetoe, Mark (2007). Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training, p.8. The Aasgaard Company. p. 320. ISBN 0976805421.

- ^ a b "Bodyweight Squat". acefitness.org. American Council on Exercise. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Brown, SP (2000). Introduction to exercise science. Lippincott Wims & Wilkins. pp. 280–1. ISBN 0683302809.

- ^ Bompa, Di Pasquale & Cornacchia, 2002, p. 121, 125.

- ^ McRobert, S (1999). The Insider's Tell-All Handbook on Weight-Lifting Technique. CS Publishing. ISBN 9963616038.

- ^ http://www.powerliftingwatch.com/records/raw/world

- ^ http://www.powerliftingwatch.com/node/7143

- ^ "New record for Sumo Squats". Guinness World Records. 2007-12-16. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ Bompa, Di Pasquale & Cornacchia, 2002, p. 120.

http://train.elitefts.com/exercise-index/barbell/the-box-squat/

References

- Cornacchia, Lorenzo; Bompa, Tudor O.; Di Pasquale, Mauro G.; Mauro Di Pasquale (2003). Serious strength training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. ISBN 0-7360-4266-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- "Bodyweight Squat". acefitness.org. American Council on Exercise. Retrieved 27 March 2011.