Electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis (pronounced /iˌlɛkˈtrɒl[invalid input: 'ɨ']sɪs/, from the Greek ἤλεκτρον [ɛ̌ːlektron] "amber" and λύσις [lýsis] "dissolution") is a method of using a direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially highly important as a stage in the separation of elements from naturally occurring sources such as ores using an electrolytic cell.

History

- 1800 – William Nicholson and Johann Ritter decomposed water into hydrogen and oxygen.

- 1807 – Potassium, sodium, barium, calcium and magnesium were discovered by Sir Humphry Davy using electrolysis.

- 1875 – Paul Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran discovered gallium using electrolysis.[1]

- 1886 – Fluorine was discovered by Henri Moissan using electrolysis.

- 1886 – Hall-Héroult process developed for making aluminium

- 1890 – Castner-Kellner process developed for making sodium hydroxide

Overview

Electrolysis is the passage of a direct electric current through an ionic substance that is either molten or dissolved in a suitable solvent, resulting in chemical reactions at the electrodes and separation of materials.

The main components required to achieve electrolysis are :

- An electrolyte : a substance containing free ions which are the carriers of electric current in the electrolyte. If the ions are not mobile, as in a solid salt then electrolysis cannot occur.

- A direct current (DC) supply : provides the energy necessary to create or discharge the ions in the electrolyte. Electric current is carried by electrons in the external circuit.

- Two electrodes : an electrical conductor which provides the physical interface between the electrical circuit providing the energy and the electrolyte

Electrodes of metal, graphite and semiconductor material are widely used. Choice of suitable electrode depends on chemical reactivity between the electrode and electrolyte and the cost of manufacture.

Process of electrolysis

The key process of electrolysis is the interchange of atoms and ions by the removal or addition of electrons from the external circuit. The required products of electrolysis are in some different physical state from the electrolyte and can be removed by some physical processes. For example, in the electrolysis of brine to produce hydrogen and chlorine, the products are gaseous. These gaseous products bubble from the electrolyte and are collected.[2]

- 2 NaCl + H2O → 2 NaOH + H2 + Cl2

A liquid containing mobile ions (electrolyte) is produced by

- Solvation or reaction of an ionic compound with a solvent (such as water) to produce mobile ions

- An ionic compound is melted (fused) by heating

An electrical potential is applied across a pair of electrodes immersed in the electrolyte.

Each electrode attracts ions that are of the opposite charge. Positively charged ions (cations) move towards the electron-providing (negative) cathode, whereas negatively charged ions (anions) move towards the positive anode.

At the electrodes, electrons are absorbed or released by the atoms and ions. Those atoms that gain or lose electrons to become charged ions pass into the electrolyte. Those ions that gain or lose electrons to become uncharged atoms separate from the electrolyte. The formation of uncharged atoms from ions is called discharging.

The energy required to cause the ions to migrate to the electrodes, and the energy to cause the change in ionic state, is provided by the external source of electrical potential.

Oxidation and reduction at the electrodes

Oxidation of ions or neutral molecules occurs at the anode, and the reduction of ions or neutral molecules occurs at the cathode. For example, it is possible to oxidize ferrous ions to ferric ions at the anode:

- Fe2+

aq → Fe3+

aq + e–

It is also possible to reduce ferricyanide ions to ferrocyanide ions at the cathode:

- Fe(CN)3-

6 + e– → Fe(CN)4-

6

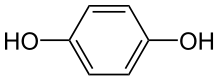

Neutral molecules can also react at either electrode. For example: p-Benzoquinone can be reduced to hydroquinone at the cathode:

In the last example, H+ ions (hydrogen ions) also take part in the reaction, and are provided by an acid in the solution, or the solvent itself (water, methanol etc.). Electrolysis reactions involving H+ ions are fairly common in acidic solutions. In alkaline water solutions, reactions involving OH- (hydroxide ions) are common.

The substances oxidised or reduced can also be the solvent (usually water) or the electrodes. It is possible to have electrolysis involving gases.

Energy changes during electrolysis

The amount of electrical energy that must be added equals the change in Gibbs free energy of the reaction plus the losses in the system. The losses can (in theory) be arbitrarily close to zero, so the maximum thermodynamic efficiency equals the enthalpy change divided by the free energy change of the reaction. In most cases, the electric input is larger than the enthalpy change of the reaction, so some energy is released in the form of heat. In some cases, for instance, in the electrolysis of steam into hydrogen and oxygen at high temperature, the opposite is true. Heat is absorbed from the surroundings, and the heating value of the produced hydrogen is higher than the electric input.

Related techniques

The following techniques are related to electrolysis:

- Electrochemical cells, including the hydrogen fuel cell, utilise differences in Standard electrode potential in order to generate an electrical potential from which useful power can be extracted. Although related via the interaction of ions and electrodes, electrolysis and the operation of electrochemical cells are quite distinct. A chemical cell should not be thought of as performing "electrolysis in reverse".

Faraday's laws of electrolysis

First law of electrolysis

In 1832, Michael Faraday reported that the quantity of elements separated by passing an electric current through a molten or dissolved salt is proportional to the quantity of electric charge passed through the circuit. This became the basis of the first law of electrolysis:

Second law of electrolysis

Faraday also discovered that the mass of the resulting separated elements is directly proportional to the atomic masses of the elements when an appropriate integral divisor is applied. This provided strong evidence that discrete particles of matter exist as parts of the atoms of elements.

Industrial uses

- Production of aluminium, lithium, sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium

- Coulometric techniques can be used to determine the amount of matter transformed during electrolysis by measuring the amount of electricity required to perform the electrolysis

- Production of chlorine and sodium hydroxide

- Production of sodium chlorate and potassium chlorate

- Production of perfluorinated organic compounds such as trifluoroacetic acid

- Production of electrolytic copper as a cathode, from refined copper of lower purity as an anode.

Electrolysis has many other uses:

- Electrometallurgy is the process of reduction of metals from metallic compounds to obtain the pure form of metal using electrolysis. For example, sodium hydroxide in its molten form is separated by electrolysis into sodium and oxygen, both of which have important chemical uses. (Water is produced at the same time.)

- Anodization is an electrolytic process that makes the surface of metals resistant to corrosion. For example, ships are saved from being corroded by oxygen in the water by this process. The process is also used to decorate surfaces.

- A battery works by the reverse process to electrolysis.

- Production of oxygen for spacecraft and nuclear submarines.

- Electroplating is used in layering metals to fortify them. Electroplating is used in many industries for functional or decorative purposes, as in vehicle bodies and nickel coins.

- Production of hydrogen for fuel, using a cheap source of electrical energy.

- Electrolytic Etching of metal surfaces like tools or knives with a permanent mark or logo.

Electrolysis is also used in the cleaning and preservation of old artifacts. Because the process separates the non-metallic particles from the metallic ones, it is very useful for cleaning old coins and even larger objects.

Competing half-reactions in solution electrolysis

Using a cell containing inert platinum electrodes, electrolysis of aqueous solutions of some salts leads to reduction of the cations (e.g., metal deposition with, e.g., zinc salts) and oxidation of the anions (e.g. evolution of bromine with bromides). However, with salts of some metals (e.g. sodium) hydrogen is evolved at the cathode, and for salts containing some anions (e.g. sulfate SO42−) oxygen is evolved at the anode. In both cases this is due to water being reduced to form hydrogen or oxidised to form oxygen. In principle the voltage required to electrolyse a salt solution can be derived from the standard electrode potential for the reactions at the anode and cathode. The standard electrode potential is directly related to the Gibb's free energy, ΔG, for the reactions at each electrode and refers to an electrode with no current flowing. An extract from the table of standard electrode potentials is shown below.

| Half-reaction | E° (V) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Na+ + e− ⇌ Na(s) | −2.71 | [3] |

| Zn2+ + 2e− ⇌ Zn(s) | −0.7618 | [4] |

| 2H+ + 2e− ⇌ H2(g) | ≡ 0 | |

| Br2(aq) + 2e− ⇌ 2Br− | +1.0873 | [4] |

| O2(g) + 4H+ + 4e− ⇌ 2H2O | +1.23 | [3] |

| Cl2(g) + 2e− ⇌ 2Cl− | +1.36 | [3] |

| S 2O2– 8 + 2e− ⇌ 2SO2− 4 |

+2.07 | [3] |

In terms of electrolysis, this table should be interpreted as follows

- oxidised species (often a cation) nearer the top of the table are more difficult to reduce than oxidised species further down. For example it is more difficult to reduce sodium ion to sodium metal than it is to reduce zinc ion to zinc metal.

- reduced species (often an anion) near the bottom of the table are more difficult to oxidise than reduced species higher up. For example it is more difficult to oxidise sulfate anions than it is to oxidise bromide anions.

Using the Nernst equation the electrode potential can be calculated for a specific concentration of ions, temperature and the number of electrons involved. For pure water (pH 7):

- the electrode potential for the reduction producing hydrogen is −0.41 V

- the electrode potential for the oxidation producing oxygen is +0.82 V.

Comparable figures calculated in a similar way, for 1M zinc bromide, ZnBr2, are −0.76 V for the reduction to Zn metal and +1.10 V for the oxidation producing bromine. The conclusion from these figures is that hydrogen should be produced at the cathode and oxygen at the anode from the electrolysis of water which is at variance with the experimental observation that zinc metal is deposited and bromine is produced.[5] The explanation is that these calculated potentials only indicate the thermodynamically preferred reaction. In practice many other factors have to be taken into account such as the kinetics of some of the reaction steps involved. These factors together mean that a higher potential is required for the reduction and oxidation of water than predicted, and these are termed overpotentials. Experimentally it is known that overpotentials depend on the design of the cell and the nature of the electrodes.

For the electrolysis of a neutral (pH 7) sodium chloride solution, the reduction of sodium ion is thermodynamically very difficult and water is reduced evolving hydrogen leaving hydroxide ions in solution. At the anode the oxidation of chlorine is observed rather than the oxidation of water since the overpotential for the oxidation of chloride to chlorine is lower than the overpotential for the oxidation of water to oxygen. The hydroxide ions and dissolved chlorine gas react further to form hypochlorous acid. The aqueous solutions resulting from this process is called electrolyzed water and is used as a disinfectant and cleaning agent.

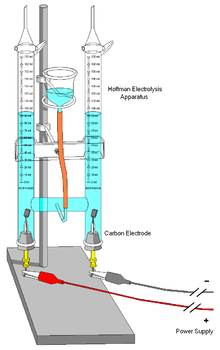

Electrolysis of water

One important use of electrolysis of water is to produce hydrogen.

- 2 H2O(l) → 2 H2(g) + O2(g); E0 = +1.229 V

Hydrogen can be used as a fuel for powering internal combustion engines by combustion or electric motors via hydrogen fuel cells (see Hydrogen vehicle). This has been suggested as one approach to shift economies of the world from the current state of almost complete dependence upon hydrocarbons for energy (See hydrogen economy.)

The energy efficiency of water electrolysis varies widely. The efficiency is a measure of what fraction of electrical energy used is actually contained within the hydrogen. Some of the electrical energy is converted to heat, an almost useless byproduct. Some reports quote efficiencies between 50% and 70%.[6] This efficiency is based on the Lower Heating Value of Hydrogen. The Lower Heating Value of Hydrogen is total thermal energy released when hydrogen is combusted minus the latent heat of vaporisation of the water. This does not represent the total amount of energy within the hydrogen, hence the efficiency is lower than a more strict definition. Other reports quote the theoretical maximum efficiency of electrolysis as being between 80% and 94%.[7] The theoretical maximum considers the total amount of energy absorbed by both the hydrogen and oxygen. These values refer only to the efficiency of converting electrical energy into hydrogen's chemical energy. The energy lost in generating the electricity is not included. For instance, when considering a power plant that converts the heat of nuclear reactions into hydrogen via electrolysis, the total efficiency is more likely to be between 25% and 40%.[citation needed]

NREL found that a kilogram of hydrogen (roughly equivalent to a gallon of gasoline) could be produced by wind powered electrolysis for between $5.55 in the near term and $2.27 in the long term.[8]

About four percent of hydrogen gas produced worldwide is created by electrolysis, and normally used onsite. Hydrogen is used for the creation of ammonia for fertilizer via the Haber process, and converting heavy petroleum sources to lighter fractions via hydrocracking.

Experimenters

Scientific pioneers of electrolysis include:

Pioneers of batteries:

More recently, electrolysis of heavy water was performed by Fleischmann and Pons in their famous experiment, resulting in anomalous heat generation and the discredited claim of cold fusion.

See also

References

- ^ Sir William Crookes (1775). The Chemical news and journal of industrial science; with which is incorporated the "Chemical gazette.": A journal of practical chemistry in all its applications to pharmacy, arts and manufactures. Chemical news office. pp. 294–. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ R. J. D. Tilley (2004). Understanding solids: the science of materials. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 281–. ISBN 978-0-470-85276-7. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d Peter Atkins (1997). Physical Chemistry, 6th edition (W.H. Freeman and Company, New York).

- ^ a b Vanýsek, Petr (2007). “Electrochemical Series”, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics: 88th Edition (Chemical Rubber Company).

- ^ A.E. Vogel, 1951, A textbook of Quantitative Inorganic Analysis, Longmans, Green and Co

- ^ Werner Zittel (1996-07-08). "Chapter 3: Production of Hydrogen. Part 4: Production from electricity by means of electrolysis". HyWeb: Knowledge – Hydrogen in the Energy Sector. Ludwig-Bölkow-Systemtechnik GmbH.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bjørnar Kruse (2002-02-13). "Hydrogen—Status and Possibilities" (PDF). The Bellona Foundation. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2002-02-13.

Efficiency factors for PEM electrolysers up to 94% are predicted, but this is only theoretical at this time.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Levene, J. (March 2006). "Wind Energy and Production of Hydrogen and Electricity – Opportunities for Renewable Hydrogen – Preprint" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)