Spanish conquest of Guatemala

The Spanish conquest of Guatemala was a conflict that formed a part of the Spanish colonization of the Americas within the territory of what became the modern country of Guatemala in Central America. Prior to the conquest, this territory contained a number of competing Mesoamerican kingdoms, the majority of which were Maya.

Many conquistadors viewed the Maya, without regard to the achievements of their civilization, as "infidels" who needed to be forcefully converted and pacified.[1] The first contact between the Maya and European explorers came in the early 16th century when a Spanish ship sailing from Panama to Santo Domingo was wrecked upon the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in 1511.[1] Several Spanish expeditions followed in 1517 and 1519, making landfall on various parts of the Yucatán coast.[2] The Spanish conquest of the Maya was a prolonged conflict, with the Maya kingdoms resisting integration into the Spanish Empire with great tenacity,[3] causing the conquest of the Maya to last almost two centuries.[4]

Pedro de Alvarado arrived in Guatemala in early 1524, commanding a mixed force of Spanish conquistadors and native allies, mostly from Tlaxcala. Placenames across Guatemala bear Nahuatl placenames due to the influence of these Mexican allies, who translated for their Spanish masters.[5] The Kaqchikel Maya initially allied themselves with the Spanish but soon rebelled against excessive Spanish demands for tribute; they did not finally surrender until 1530. In the meantime the other major highland Maya kingdoms had each been defeated in turn by the Spanish and allied warriors from both Mexico and previously subjugated Maya kingdoms in Guatemala. The Itza Maya and other lowland groups in the Petén Basin were first contacted by Hernán Cortés in 1525 but remained independent and hostile to the encroaching Spanish until 1697 when a concerted Spanish assault finally defeated the last independent Maya kingdom.

Historical sources

The sources describing the Spanish conquest of Guatemala include those written by the Spanish themselves, among them two of four letters written by conquistador Pedro de Alvarado to Hernán Cortés in 1524, describing the initial campaign to subjugate the Guatemalan highlands. These letters were dispatched to Tenochtitlan, addressed to Cortés but with a royal audience in mind; two of these letters are no longer extant.[6] Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez was Pedro de Alvarado's cousin; he accompanied him on his first campaign in Guatemala and in 1525 he became the chief constable of Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala, the newly founded Spanish capital. Gonzalo wrote an account that mostly supports that of Pedro de Alvarado. Pedro de Alvarado's brother Jorge wrote another account to the king of Spain explaining that it was his own campaign of 1527-1529 that established the Spanish colony.[7] Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote a lengthy account of the conquest of Mexico and neighbouring regions, the Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España ("True History of the Conquest of New Spain"), his account of the conquest of Guatemala generally agrees with that of the Alvarados.[8] His account was finished around 1568, some 40 years after the campaigns it describes.[9] Hernán Cortés described his expedition to Honduras in the fifth letter of his Cartas de Relación,[10] in which he details his crossing of what is now Guatemala's Petén Department. Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas wrote a highly critical account of the Spanish conquest of the Americas and included accounts of some incidents in Guatemala.[11] The Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias ("Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies") was first published in 1552 in Seville.[12]

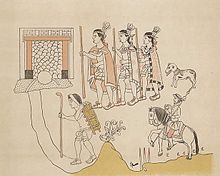

The Tlaxcalan allies of the Spanish who accompanied them in their invasion of Guatemala wrote their own accounts of the conquest, these included a letter to the Spanish king protesting at the poor treatment of these allies once the campaign was over. Other accounts were in the form of questionnaires answered before colonial magistrates in order to protest and register a claim for recompense.[13] Two pictorial accounts painted in the stylised indigenous pictographic tradition have survived, these are the Lienzo de Quauhquechollan, which was probably painted in Ciudad Vieja in the 1530s, and the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, painted in Tlaxcala.[14]

Accounts of the conquest as seen from the point of view of the defeated highland Maya kingdoms are included in a number of indigenous documents, including the Annals of the Kaqchikels, which includes the Xajil Chronicle describing the history of the Kaqchikel from their mythical creation down through the Spanish conquest and continuing to 1619.[15] A letter from the defeated Tz'utujil Maya nobility of Santiago Atitlán to the Spanish king was written in 1571, detailing the heavy exploitation of the subjugated peoples.[16]

Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán was a colonial Guatemalan historian of Spanish descent who wrote La Recordación Florida, also called Historia de Guatemala (History of Guatemala). The book was written in 1690 and is regarded as one of the most important works of Guatemalan history, and is the first such book to have been written by a criollo author.[17]

Guatemala prior to the conquest

In the early 16th century the territory that now makes up Guatemala was divided into various competing polities, each locked in continual struggle with its neighbours.[18] The most important of these were the K'iche', the Kaqchikel, the Tz'utujil, the Chajoma,[19] the Mam, the Poqomam and the Pipil.[20] All of these were Maya groups, with the exception of the Pipil, who were instead a Nahua group related to the Aztecs; they had a number of small city-states along the Pacific coastal plain of southern Guatemala and El Salvador.[21] The Pipil of Guatemala had their capital at Itzcuintepec.[22] The Xinca were another non-Maya group occupying the southeastern Pacific coastal area.[23] The Maya had never been unified as a single empire and by the time the Spanish arrived Maya civilization was thousands of years old and had already seen the rise and fall of great cities.[24]

On the eve of the conquest the highlands of Guatemala were dominated by several powerful Maya states.[25] In the centuries preceding the arrival of the Spanish the K'iche' had carved out a small empire covering a large part of the western Guatemalan Highlands and the neighbouring Pacific coastal plain.[26] However, in the late 15th century the Kaqchikel allies of the K'iche' rebelled against their former overlords and founded a new kingdom to the southeast with Iximche as its capital. In the decades prior to the Spanish invasion the Kaqchikel kingdom had been steadily eroding the kingdom of the K'iche'.[26] Other highland groups included the Tz'utujil around Lake Atitlán, the Mam in the western highlands and the Poqomam in the eastern highlands.[20]

The kingdom of the Itza was the most powerful polity in the Petén lowlands of northern Guatemala,[27] centred upon their capital Nojpetén on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá. The second most important polity was that of their hostile neighbours, the Kowoj. The Kowoj were located to the east of the Itza, around the eastern lakes: Lake Salpetén, Lake Macanché, Lake Yaxhá and Lake Sacnab.[28] Other groups are less well known and their precise territorial extent and political makeup remains obscure, among these are included the Chinamita, the Kejache, the Icaiche, the Lacandon, the Mopan, the Manche Ch'ol and the Yalain.[29] The Kejache occupied an area north of the lake upon the route to Campeche, while both the Mopan and the Chinamita had their polities in the southeastern Petén.[30] The Manche territory was to the southwest of the Mopan.[31]

Native weapons and tactics

The Spanish described the weapons of war of the Petén Maya as bows and arrows, fire-sharpened poles, flint-headed spears and two-handed swords crafted from strong wood with the blade fashioned from inset obsidian,[32] similar to the Aztec macuahuitl. Pedro de Alvarado described how the Xinca of the Pacific coast attacked the Spanish with spears, stakes and poisoned arrows.[33] In response to the use of cavalry the highland Maya took to digging pits on the roads, lining them with fire-hardened stakes and camouflaging them with grass and weeds, a tactic that the Kaqchikel claimed killed many horses.[34]

The Spanish

The conquistadors were all volunteers, the majority of whom did not receive a fixed salary but rather received a portion of the spoils of victory, in the form of precious metals, land grants and provision of native labour.[35] Many of the Spanish were already experienced soldiers who had previously campaigned in Europe.[36] The initial incursion into Guatemala was led by Pedro de Alvarado who would earn the military title of Adelantado in 1527;[37] he answered to the Spanish crown via Hernán Cortés in Mexico.[36] Other early conquistadors included Pedro de Alvarado's brothers Gómez de Alvarado, Jorge de Alvarado and Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras; and his cousins Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez, Hernando de Alvarado and Diego de Alvarado.[7] Pedro de Portocarrero was a nobleman who joined the initial invasion.[38] Bernal Díaz del Castillo was a petty nobleman who accompanied Hernán Cortés when he crossed the northern lowlands and also accompanied Pedro de Alvarado's invasion of the highlands.[39]

Spanish weapons and tactics

Spanish weaponry and tactics differed greatly from that of the indigenous peoples of Guatemala. This included the use of crossbows, firearms (including muskets and cannon),[40] war dogs and war horses.[41] Among Mesoamerican peoples the capture of prisoners was a priority while to the Spanish such taking of prisoners was a hindrance to outright victory.[41] The inhabitants of Guatemala, for all their sophistication, lacked key elements of Old World technology, such as the use of iron and steel and functional wheels.[42] The use of steel swords was perhaps the greatest technological advantage held by the Spanish, although the deployment of cavalry helped the Spanish rout indigenous armies on occasion.[43]

In Guatemala the Spanish routinely fielded indigenous allies, at first these were Nahua allies brought from the recently conquered Mexico, later on these allies also included Maya. It is estimated that for every Spaniard on the field of battle, there were at least 10 native auxiliaries. Sometimes there were as many as 30 indigenous warriors for every Spaniard, and it was the participation of these Mesoamerican allies that was particularly decisive.[44]

The Spanish engaged in a strategy of concentrating native populations in newly founded colonial towns, or reducciones. Native resistance to the new nucleated settlements took the form of the flight of the indigenous inhabitants into inaccessible regions such as mountains and forests.[45]

Impact of Old World diseases

Epidemics accidentally introduced by the Spanish included smallpox, measles and influenza. These diseases, together with typhus and yellow fever, had a major impact on Maya populations.[46] The Old World diseases brought with the Spanish and against which the indigenous New World peoples had no resistance were a deciding factor in the conquest, with the diseases crippling armies and decimating populations before battles were even fought.[47] The introduction of these diseases was catastrophic in the Americas; it is estimated that 90% of the indigenous population had been eliminated by disease within the first century of European contact.[48]

In 1519 and 1520, prior to the arrival of the Spanish in the region, a number of epidemics swept through southern Guatemala.[49] At the same time as the Spanish were occupied with the overthrow of the Aztec empire a terrible plague struck the Kaqchikel capital of Iximche, and the city of Q'umarkaj, capital of the K'iche', may also have suffered from the same epidemic.[50] In 1666 pestilence or murine typhus swept through what is now the department of Huehuetenango. Smallpox was reported in San Pedro Saloma, in 1795.[51] At the time of the fall of Nojpetén in 1697, there are estimated to have been 60,000 Maya living around Lake Petén Itzá, including a large number of refugees from other areas. It is estimated that 88% of these died during the first ten years of colonial rule due to a combination of disease and war.[52]

Timeline of the conquest

| Date | Event | Modern department (or Mexican state) |

|---|---|---|

| 1521 | Conquest of Tenochtitlan | Mexico |

| 1522 | Spanish allies scout Soconusco and receive delegations from the K'iche' and Kaqchikel | Chiapas, Mexico |

| 1523 | Pedro de Alvarado arrives in Soconusco | Chiapas, Mexico |

| February - March 1524 | Spanish defeat the K'iche' | Retalhuleu, Suchitepéquez, Quetzaltenango, Totonicapán and El Quiché |

| 8 February 1524 | Battle of Zapotitlán, Spanish victory over the K'iche' | Suchitepéquez |

| 12 February 1524 | 1st battle of Quetzaltenango results in the death of the K'iche' lord Tecun Uman | Quetzaltenango |

| 18 February 1524 | 2nd battle of Quetzaltenango | Quetzaltenango |

| March 1524 | Spanish under Pedro de Alvarado raze Q'umarkaj, capital of the K'iche' | El Quiché |

| 14 April 1524 | Spanish enter Iximche and ally themselves with the Kaqchikel | Chimaltenango |

| 18 April 1524 | Spanish defeat the Tz'utujil in battle on the shores of Lake Atitlán | Sololá |

| 9 May 1524 | Pedro de Alvarado defeats the Pipil of Panacal or Panacaltepeque near Izcuintepeque | Escuintla |

| 26 May 1524 | Pedro de Alvarado defeats the Xinca of Atiquipaque | Santa Rosa |

| 27 July 1524 | Iximche declared first colonial capital of Guatemala | Chimaltenango |

| 28 August 1524 | Kaqchikel abandon Iximche and break alliance | Chimaltenango |

| 7 September 1524 | Spanish declare war on the Kaqchikel | Chimaltenango |

| 1525 | The Poqomam capital falls to Pedro de Alvarado | Guatemala |

| 13 March 1525 | Hernán Cortés arrives at Lake Petén Itzá | Petén |

| October 1525 | Zaculeu, capital of the Mam, surrenders to Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez after a lengthy siege | Huehuetenango |

| 1526 | Chajoma rebel against the Spanish | Guatemala |

| 9 February 1526 | Spanish deserters burn Iximche | Chimaltenango |

| 1527 | Spanish abandon their capital at Tecpán Guatemala | Chimaltenango |

| 1529 | San Mateo Ixtatán given in encomienda to Gonzalo de Ovalle | Huehuetengo |

| 9 May 1530 | Kaqchikel surrender to the Spanish | Sacatepéquez |

| 1549 | First reductions of the Chuj and Q'anjob'al | Huehuetenango |

| 1618 | Franciscan missionaries arrive at Nojpetén, capital of the Itzá | Petén |

| 1619 | Further missionary expeditions to Nojpetén | Petén |

| 1684 | Reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán and Santa Eulalia | Huehuetenango |

| 29 January 1686 | Melchor Rodríguez Mazariegos leaves Huehuetenango, leading an expedition against the Lacandón | Huehuetenango |

| 1695 | Franciscan friar Andrés de Avendaño attempts to convert the Itzá | Petén |

| 28 February 1695 | Spanish expeditions leave simultaneously from Cobán, San Mateo Ixtatán and Ocosingo against the Lacandón | Alta Verapaz, Huehuetenango and Chiapas |

| 1696 | Andrés de Avendaño forced to flee Nojpetén | Petén |

| 13 March 1697 | Nojpetén falls to the Spanish after a fierce battle | Petén |

Conquest of the highlands

After Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztecs, fell to the Spanish in 1521, the Kaqchikel Maya of Iximche sent envoys to Hernán Cortés to declare their allegiance to the new ruler of Mexico, and the K'iche' Maya of Q'umarkaj may also have sent a delegation.[53] In 1522 Cortés sent Mexican allies to scout the Soconusco region of lowland Chiapas, where they met new delegations from both Iximche and Q'umarkaj at Tuxpán,[54] with both of the powerful highland Maya kingdoms declaring their loyalty to the king of Spain.[53] Cortés' allies in Soconusco soon informed him that the K'iche' and the Kaqchikel were not loyal, instead harassing the allies of Spain in the region. Due to this Cortés despatched Pedro de Alvarado with 180 cavalry, 300 infantry, crossbows, muskets, 4 cannons, large amounts of ammunition and gunpowder, and allied Mexican warriors. They arrived in Soconusco in 1523.[53] Pedro de Alvarado was infamous for the massacre of Aztec nobles in Tenochtitlan and, according to Bartolomé de las Casas, he committed further atrocities in the conquest of the Maya kingdoms in Guatemala.[55] Some groups remained loyal to the Spanish once they had submitted to the conquest, such as the Tz'utijil and the K'iche' of Quetzaltenango, and provided them with warriors to assist further conquest. Other groups soon rebelled however, and by 1526 numerous rebellions had engulfed the highlands.[56]

Subjugation of the K'iche'

Pedro de Alvarado advanced with his army along the Pacific coast without opposition until they reached the Samalá River in western Guatemala. This region formed a part of the K'iche' kingdom and a K'iche' army tried to prevent the Spanish from crossing the river. Their resistance failed and the conquistadors crossed the river and ransacked nearby settlements in order to terrorise the K'iche' resistance.[5] On 8 February 1524, after forcing their way across the river, Alvarado's army fought a battle at Xetulul, called Zapotitlán by his Mexican allies (modern San Francisco Zapotitlán). Although suffering many injuries from defending K'iche' archers, the Spanish and their allies stormed the town and set up camp in the marketplace.[57] Alvarado then turned to head upriver into the Sierra Madre mountains towards the K'iche' heartlands, crossing the pass into the fertile valley of Quetzaltenango. On 12 February 1524 Alvarado's Mexican allies were ambushed in the pass and driven back by the K'iche' warriors but the Spanish cavalry charge that followed was a shock for the K'iche' who had never seen horses before. The cavalry scattered the K'iche' and the army crossed to the city of Xelaju, modern Quetzaltenango, to find it deserted by its inhabitants.[58] Although the common view is that the K'iche' prince Tecun Uman died in the later battle near Olintepeque, the Spanish accounts are clear that at least one and possibly two of the lords of Q'umarkaj died in the fierce battles upon the initial approach to Quetzaltenango.[59] The death of Tecun Uman is said to have taken place in the battle of El Pinar,[60] and local tradition has his death taking place upon the Llanos de Urbina (Plains of Urbina), upon the approach to Quetzaltenango near the modern village of Cantel.[61] Pedro de Alvardo, in his 3rd letter to Hernán Cortés, describes the death of one of the four lords of Q'umarkaj upon the approach to Quetzaltenango. The letter was dated 11 April 1524 and was written during his stay at Q'umarkaj.[60] Almost a week later, on 18 February 1524,[62] a K'iche' army confronted the Spanish army in the Quetzaltenango valley where they were comprehensively defeated, with many K'iche' nobles among the dead.[63] Such were the numbers of K'iche' dead that Olintepeque was given the new name Xequiquel, roughly meaning "bathed in blood".[64] This battle exhausted the K'iche' militarily and they asked for peace and offered tribute, inviting Pedro de Alvarado into their capital Q'umarkaj, which was known as Tecpan Utatlan to the Nahuatl-speaking allies of the Spanish. Alvarado was deeply suspicious of the K'iche' intentions but accepted the offer and marched to Q'umarkaj with his army.[65]

In March 1524, Pedro de Alvarado entered Q'umarkaj when invited by the remaining lords of the K'iche' after the catastrophic defeat of the K'iche' army in the Quetzaltenango valley.[66] Alvarado feared that a trap had been laid for him by the K'iche' lords but entered the city anyway.[63] However, he encamped on the plain outside the city rather than accepting lodgings inside.[67] Fearing the great number of K'iche' warriors gathered outside the city and that his cavalry would not be able to maneouvre in the narrow streets of Q'umarkaj, he invited the highest lords of the city, Oxib-Keh (the ajpop, or king) and Beleheb-Tzy (the ajpop k'amha, or king elect) to visit him in his camp.[68] As soon as they did so, he seized them and kept them as prisoners in his camp.[69] The K'iche' warriors, seeing their lords taken prisoner, attacked the Spaniards' indigenous allies and managed to kill one of the Spanish soldiers.[69] At this point Alvarado decided to have the captured K'iche' lords burnt to death, he then proceeded to burn the entire city.[70] With the destruction of Q'umarkaj and the execution of its rulers, Pedro de Alvarado sent messages to Iximche, capital of the Kaqchikel, proposing an alliance against the remaining K'iche' resistance. Alvarado wrote that they sent 4000 warriors to assist him, although the Kaqchikel recorded that they only sent 400.[65]

Kaqchikel alliance

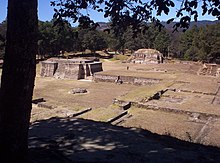

On 14 April 1524, soon after the defeat of the K'iche', the Spanish were invited into Iximche and were well received by the lords Belehe Qat and Cahi Imox.[71][nb 1] The Kaqchikel kings provided native soldiers to assist the conquistadors against continuing K'iche' resistance and to help with the defeat of the neighbouring Tz'utuhil kingdom.[72] The Spanish only stayed briefly in Iximche before continuing through Atitlán, Escuintla and Cuscatlán.[73] The Spanish returned to the Kaqchikel capital on 23 July 1524 and on 27 July (1 Q'at in the Kaqchikel calendar) Pedro de Alvarado declared Iximche as the first capital of Guatemala, Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala ("St. James of the Knights of Guatemala").[73] Iximche was called Guatemala by the Spanish, from the Nahuatl Quauhtemallan meaning "forested land". Since the Spanish conquistadors founded their first capital at Iximche, they took the name of the city used by their Nahuatl-speaking Mexican allies and applied it to the new Spanish city and, by extension, to the kingdom. From this comes the modern name of the country.[74]

Conquest of the Tz'utujil

The Kaqchikel appear to have entered into an alliance with the Spanish in order to defeat their enemies, the Tz'utujil, whose capital was Tecpan Atitlan.[65] Pedro de Alvarado sent two Kaqchikel messengers to Tecpan Atitlan at the request of the Kaqchikel lords; both messengers were killed by the Tz'utujil.[75] When news of the killing of the messengers reached the Spanish at Iximche, the conquistadors marched against the Tz'utujil with their Kaqchikel allies.[65] Pedro de Alvarado left Iximche just 5 days after he had arrived there, with 60 cavalry, 150 Spanish infantry and an unspecified number of Kaqchikel warriors.[76] The Spanish and their allies arrived at the lakeshore after a day's hard march, without encountering any opposition.[76] Seeing the lack of resistance, Alvarado rode ahead with 30 cavalry along the lake shore. Opposite a populated island the Spanish at last encountered hostile Tz'utujil warriors and charged among them, scattering them and pursuing them to a narrow causeway across which the surviving Tz'utujil fled.[76] The causeway was too narrow for the horses, so the conquistadors dismounted and crossed to the island before the inhabitants could break the bridges.[77] The rest of Alvarado's army soon reinforced his party and they successfully stormed the island. The surviving Tz'utujil fled into the lake and swam to safety on another island.[78] The Spanish could not pursue the survivors further because 300 canoes sent by the Kaqchikels had not yet arrived.[78] This battle took place on 18 April.[78]

The following day the Spanish entered Tecpan Atitlan but found it deserted. Pedro de Alvarado camped in the centre of the city and sent out scouts to find the enemy. They managed to catch some locals and used them to send messages to the Tz'utujil lords, ordering them to submit to the king of Spain. The Tz'utujil leaders responded by surrendering to Pedro de Alvarado and swearing loyalty to Spain, at which point Alvarado considered them pacified and returned to Iximche.[78] Three days after Pedro de Alvarado returned to Iximche, the lords of the Tz'utujil arrived there to pleadge their loyalty and offer tribute to the conquistadors.[79] A short time afterwards a number of lords arrived from the Pacific lowlands to swear allegiance to the king of Spain, although Alvarado did not name them in his letters; they confirmed Kaqchikel reports that further out on the Pacific plain was the kingdom called Izcuintepeque in Nahuatl, or Panatacat in Kaqchikel, whose inhabitants were warlike and hostile towards their neighbours.[80]

Kaqchikel rebellion

Pedro de Alvarado rapidly began to demand gold in tribute from the Kaqchikels, souring the friendship between the two peoples.[81] He demanded that the Kaqchikel kings deliver 1000 gold leaves each of 15 pesos.[82] A Kaqchikel priest foretold that the Kaqchikel gods would destroy the Spanish and the Kaqchikel people abandoned their city and fled to the forests and hills on 28 August 1524 (7 Ahmak in the Kaqchikel calendar).[81] Ten days later the Spanish declared war on the Kaqchikel.[81] Two years later, on 9 February 1526, a group of sixteen Spanish deserters burnt the palace of the Ahpo Xahil, sacked the temples and kidnapped a priest, acts that the Kaqchikel blamed on Pedro de Alvarado.[83][nb 2] Conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo recounted how in 1526 he returned to Iximche and spent the night in the "old city of Guatemala" together with Luis Marín and other members of Hernán Cortés's expedition to Honduras.[84] He reported that the houses of the city were still in excellent condition, his account was the last description of the city while it was still inhabitable.[84]

The Spanish founded a new town at nearby Tecpán Guatemala, with Tecpán being Nahuatl for "palace", so the name of the new town translated as "the palace among the trees".[85] The Spaniards abandoned Tecpán in 1527, due to the continuous Kaqchikel attacks, and moved to the Almolonga Valley to the east, refounding their capital on the site of today's San Miguel Escobar district of Ciudad Vieja, near Antigua Guatemala.[86]

The Kaqchikel kept up resistance against the Spanish for a number of years but on 9 May 1530, exhausted by the warfare that had seen the deaths of their best warriors and the enforced abandonment of their crops,[87] the two kings of the most important clans returned from the wilds.[81] A day later they were joined by many nobles and their families and many more people and then surrendered at the new Spanish capital at Ciudad Vieja.[81] The former inhabitants of Iximche were dispersed, with some being moved to Tecpán, others to Sololá and to other towns around Lake Atitlán.[85]

Siege of Zaculeu

Although a state of hostilities existed between the Mam and the K'iche' of Q'umarkaj after the rebellion of the Kaqchikel against their former K'iche' allies prior to European contact, when the conquistadors arrived there was a shift in the political landscape. Pedro de Alvarado described how the Mam king Kayb'il B'alam was received with great honour in Q'umarkaj while he was there.[88]

At the time of the conquest, the main Mam population was situated in Xinabahul (also spelled Chinabjul), now the city of Huehuetenango, but Zaculeu's fortifications led to its use as a refuge during the conquest.[89] The refuge was attacked by Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez, cousin of conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, in 1525,[90] with 120 soldiers, and some 2,000 Mexican and K'iche' allies.[91] The city was defended by Kayb'il B'alam[89] commanding some 5,000 people (the chronicles are not clear if this is the number of soldiers or the total population of Zaculeu).

After a siege lasting several months the Mam were reduced to starvation. Kayb'il B'alam finally surrendered the city to the Spanish in October of 1525.[89][92] When the Spanish entered the city they found 1,800 dead Indians, with the survivors eating the corpses of the dead.[91] After this Zaculeu was abandoned, and the new city of Huehuetenango established some 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) away.

Conquest of the Poqomam

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Maya civilization |

|---|

|

| History |

| Spanish conquest of the Maya |

|

|

In 1525 Pedro de Alvarado sent a small company to conquer Mixco Viejo, the capital of the Poqomam.[nb 3] At the Spanish approach, the inhabitants remained enclosed in the fortified city. The Spanish attempted an approach from the west through a narrow pass but were forced back with heavy losses. Alvarado himself launched the second assault with 200 Tlaxcalan allies but was also beaten back. The Poqomam then received reinforcements, possibly from Chinautla, and the two armies clashed on open ground outside of the city. The battle was chaotic and lasted for most of the day but was finally decided by the Spanish cavalry, forcing the Poqomam reinforcements to withdraw.[93] The leaders of the reinforcements surrendered to the Spanish three days after their retreat and revealed that the city had a secret entrance in the form of a cave leading up from a nearby river, allowing the inhabitants to come and go.[94]

Armed with the knowledge gained from their prisoners, Alvarado sent 40 men to cover the exit from the cave and launched another assault along the ravine from the west, in single file owing to its narrowness, with crossbowmen alternating with soldiers bearing muskets, each with a companion sheltering him from arrows and stones with a shield. This tactic allowed the Spanish to break through the pass and storm the entrance of the city. The Poqomam warriors fell back in disorder in a chaotic retreat through the city, and were hunted down by the victorious conquistadors and their allies. Those who managed to retreat down the neighbouring valley were ambushed by Spanish cavalry who had been posted to block the exit from the cave, the survivors were captured and brought back to the city. The siege had lasted more than a month and due to the defensive strength of the city, Alvarado ordered it to be burned and moved the inhabitants to the new colonial village of Mixco.[93]

Resettlement of the Chajoma

There are no direct sources describing the conquest of the Chajoma by the Spanish but it appears to have been a drawn-out campaign rather than a rapid victory.[95] The only description of the conquest of the Chajoma is a secondary account appearing in the work of Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán in the 17th century, long after the event.[96] After the conquest, the inhabitants of the eastern part of the kingdom were relocated by the conquerors to San Pedro Sacatepéquez, including some of the inhabitants of the archaeological site now known as Mixco Viejo. The rest of the population of Mixco Viejo, together with the inhabitants of the western part of the kingdom, were moved to San Martín Jilotepeque.[95]

The Chajoma rebelled against the Spanish in 1526, fighting a battle at Ukub'il, an unidentified site somewhere near the modern towns of San Juan Sacatepéquez and San Pedro Sacatepéquez.[97]

In the colonial period, most of the surviving Chajoma were forcibly settled in the towns of San Juan Sacatepéquez, San Pedro Sacatepéquez and San Martín Jilotepeque as a result of the Spanish policy of congregaciones, with the people being moved to whichever of these three towns was closest to their pre-conquest land holdings. Some Iximche Kaqchikels seem also to have been relocated to the same towns.[98] After their relocation to the new towns, some of the Chajoma drifted back to their pre-conquest centres, creating informal settlements and provoking hostilities with the Poqomam of Mixco and Chinautla along the former border between the pre-Columbian kingdoms. Some of these settlements eventually received official recognition, such as San Raimundo near Sacul.[96]

Campaigns in the Cuchumatanes

In the ten years after the fall of Zaculeu various Spanish expeditions crossed into the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes and engaged in the gradual and complex conquest of the Chuj and Q'anjob'al.[99] The Spanish were attracted to the region in the hope of extracting gold, silver and other riches from the mountains but their remoteness, the difficult terrain and relatively low population made their conquest and exploitation extremely difficult.[100]

In 1529, four years after the conquest of Huehuetenango, the Chuj city of San Mateo Ixtatán (then known by the name of Ystapalapán) was given in encomienda to the conquistador Gonzalo de Ovalle, a companion of Pedro de Alvarado, together with Santa Eulalia and Jacaltenango.[101] In 1549, the first reduction (reducción in Spanish) of San Mateo Ixtatán took place, overseen by Dominican missionaries,[101] in the same year the Q'anjob'al reducción settlement of Santa Eulalia was founded.[45] Further Q'anjob'al reducciones were in place at San Pedro Soloma, San Juan Ixcoy and San Miguel Acatán by 1560.[45] Q'anjob'al resistance was largely passive, based upon withdrawal to the inaccessible mountains and forests from the Spanish reducciones. In 1586 the Mercedarian Order built the first church in Santa Eulalia.[45] The Chuj of San Mateo Ixtatán remained rebellious and resisted Spanish control for longer than their highland neighbours, resistance that was possible due to their alliance with the lowland Lacandon to the north. The continued resistance was so determined that the Chuj remained pacified only while the immediate effects of the Spanish expeditions lasted.[102]

In the late 17th century, the Spanish missionary Fray Alonso de León reported that about eighty families in San Mateo Ixtatán did not pay tribute to the Spanish Crown or attend the Roman Catholic mass.[103] He described the inhabitants as quarrelsome and complained that they had built a pagan shrine in the hills among the ruins of pre-Columbian temples, where they burnt incense and offerings and sacrificed turkeys.[103] He reported that every March they built bonfires around wooden crosses about two leagues from the town and set them on fire.[103] Fray de León informed the colonial authorities that the practices of the natives were such that they were Christian in name only.[103] Eventually, Fray de León was chased out of San Mateo Ixtatán by the locals.[103]

In 1684, a council led by Enrique Enriquez de Guzmán, the then governor of Guatemala, decided upon the reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán and nearby Santa Eulalia, both within the colonial administrative district of the Corregimiento of Huehuetenango.[104]

On 29 January 1686, Captain Melchor Rodríguez Mazariegos, under orders of the governor, left Huehuetenango for San Mateo Ixtatán, where he recruited indigenous warriors from the nearby villages, with 61 from San Mateo itself.[105] It was believed by the Spanish colonial authorities that the inhabitants of San Mateo Ixtatán were friendly towards the still unconquered and fiercely hostile inhabitants of the Lacandon region, which included parts of what is now the Mexican state of Chiapas and the western part of the Petén Basin.[106] In order to prevent news of the Spanish advance reaching the inhabitants of the Lacandon area, the governor ordered the capture of three community leaders of San Mateo, named as Cristóbal Domingo, Alonso Delgado and Gaspar Jorge, and had them sent under guard to be imprisoned in Huehuetenango.[107] The governor himself arrived in San Mateo Ixtatán on 3 February, where Captain Rodríguez Mazariegos was already awaiting him.[108] The governor ordered the captain to remain in the village to use it as a base of operations for penetrating the Lacandon region.[108] The Spanish missionaries Fray de Rivas and Fray Pedro de la Concepción also remained in the town.[108] After this, Governor Enriquez de Guzmán left San Mateo Ixtatán for Comitán in Chiapas, to enter the Lacandon region via Ocosingo.[109]

In 1695, a three-way invasion of the Lacandon was launched simultaneously from San Mateo Ixtatán, Cobán and Ocosingo.[110] Captain Rodriguez Mazariegos accompanied by Fray de Rivas and 6 more missionaries together with 50 Spanish soldiers left Huehuetenango for San Mateo Ixtatán, managing on the way to recruit 200 indigenous Maya warriors from Santa Eulalia, San Juan Solomá and San Mateo itself.[111] They followed the same route used in 1686.[112] On 28 February 1695, all three groups left their respective bases of operations to conquer the Lacandon.[111] The San Mateo group headed northeast into the Lacandon Jungle.[111]

The Pacific lowlands: Pipil and Xinca

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the western portion of the Pacific plain was dominated by the K'iche' and Kaqchikel states,[113] while the eastern portion was occupied by the Pipil and the Xinca.[114] The Pipil inhabited the area of the modern department of Escuintla and a part of Jutiapa;[115] the Xinca territory lay to the east of the main Pipil population in what is now Santa Rosa department.[116]

In the half century preceding the arrival of the Spanish, the Kaqchikel were frequently at war with the Pipil of Izcuintepeque (modern Escuintla).[117] By March 1524 the K'iche had been defeated, followed by a Spanish alliance with the Kaqchikel in April of the same year.[72] On 8 May 1524, soon after his arrival in Iximche and immediately following his subsequent conquest of the Tz'utujil around Lake Atitlán, Pedro de Alvarado continued southwards to the Pacific coastal plain where he defeated the Pipil of Panacal or Panacaltepeque (called Panatacat in the Annals of the Kaqchikels) near Izcuintepeque on 9 May.[118] Alvarado described the terrain approaching the town as very difficult, covered with dense vegetation and swampland that made the use of cavalry impossible; instead he sent men with crossbows ahead. The Pipil withdrew their scouts due to the heavy rain, believing that the Spanish and their allies would not be able to reach the town that day. However, Pedro de Alvarado pressed ahead and when the Spanish entered the town the defenders were completely unprepared, with the Pipil warriors indoors sheltering from the torrential rain. In the battle that ensued, the Spanish and their indigenous allies suffered minor losses but the Pipil were able to flee into the forest, sheltered from Spanish pursuit by the weather and the vegetation. Pedro de Alvarado ordered the town to be burnt and sent messengers to the Pipil lords demanding their surrender, otherwise he would lay waste to their lands.[119] According to Alvarado's letter to Cortés, the Pipil came back to the town and submitted to him, accepting the king of Spain as their overlord.[120] The Spanish force camped in the captured town for eight days.[119] A few years later, in 1529, Pedro de Alvarado was accused of using excessive brutality in his conquest of Izcuintepeque, amongst other atrocities.[121]

In Guazacapán, now a municipality in Santa Rosa, Pedro de Alvardo described his encounter with people who were neither Maya nor Pipil, speaking a different language altogether; these people were probably Xinca.[33] At this point Alvarado's force consisted of 250 Spanish infantry accompanied by 6000 indigenous allies, mostly Kaqchikel and Cholutec.[122] Alvarado and his army defeated and occupied the most important Xinca city, named as Atiquipaque, usually considered to be in the Taxisco area. The defending warriors were described by Alvarado as engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat using spears, stakes and poisoned arrows.[33] The battle took place on 26 May 1524 and resulted in a significant reduction of the Xinca population.[33]

After the conquest of the Pacific plain, the inhabitants paid tribute to the Spanish in the form of valuable products such as cacao, cotton, salt and vanilla, with an emphasis upon cacao.[123]

The northern lowlands

The Contact Period in Guatemala's northern Petén lowlands lasted from 1525 through to 1700.[124] Superior Spanish weaponry and the use of cavalry, while successful in the northern Yucatán, were little suited to warfare in the dense forests of lowland Guatemala.[125]

Cortés in Petén

In 1525, after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés led an expedition to Honduras over land, cutting across the Itza kingdom in what is now the northern Petén Department of Guatemala.[126] The aim of this expedition was to subdue the rebellious Cristóbal de Olid who he had sent to conquer Honduras. However, Cristóbal de Olid had set himself up independently once he had arrived in that territory.[127] Cortés had 140 Spanish soldiers, 93 of them mounted, 3000 Mexican warriors, 150 horses, a herd of pigs, artillery, munitions and other supplies. He also had with him 600 Chontal Maya carriers from Acalan. They arrived at the north shore of Lake Petén Itzá on 13 March 1525.[128]

Cortés was invited to Nojpetén (also known as Tayasal) by Aj Kan Ek', the king of the Itza, and accepted, crossing to the Maya city with 20 Spanish soldiers while the rest of his army continued around the lake to meet him on the south shore.[129] When he left Nojpetén, Cortés left behind a cross and a lame horse. The Spanish did not officially contact the Itza again until the arrival of Franciscan priests in 1618, when Cortés' cross was said to still be standing at Nojpetén.[126] From the lake, Cortés continued south along the western slopes of the Maya Mountains, a particularly arduous journey that took 12 days to cover 32 kilometres (20 mi), during which he lost more than two thirds of his horses. When he came to a river swollen with the constant torrential rains that had been falling during the expedition, Cortés turned upstream to the Gracias a Dios rapids, which took two days to cross, with the loss of more horses.[130]

On 15 April 1525, the expedition arrived at the Maya village of Tenciz. With local guides they headed into the hills north of Lake Izabal, where their guides abandoned them to their fate. The expedition became lost in the hills and came close to starvation before they captured a Maya boy who led them out to safety.[130] Cortés found a village on the shore of Lake Izabal, this may have been Xocolo.[131] Cortés crossed the Dulce River to the settlement of Nito, located somewhere on the Amatique Bay,[131] with about a dozen companions and there waited for the rest of his army to regroup over the course of the next week.[130] By this time the remnants of the expedition had been reduced to a few hundred; Cortés managed to contact the Spaniards he was searching for only to find that Cristóbal de Olid's own officers had already put down his rebellion. Cortés then returned to Mexico by sea.[132]

Lake Izabal and the lower Motagua River

The Dominicans established their control in Xocolo on the shore of Lake Izabal in the mid 16th century. By 1574 it was the most important staging post for European expeditions into the interior. Xocolo became infamous among the Dominican missionaries for the practice of witchcraft by its inhabitants. It remained an important European way station until as late as 1630, although it was abandoned in 1631.[133]

In 1598 Alfonso Criado de Castilla became governor of the Captaincy General of Guatemala. Due to the poor state of Puerto Caballos on the Honduran coast and its exposure to repeated pirate raids he sent a pilot to scout Lake Izabal.[133] As a result of the survey, and after royal permission was granted, Criado de Castilla ordered the construction of a new port, named Santo Tomás de Castilla, at a favourable spot on the Amatique Bay not far from the lake. Work then began on building a highway from the port to the new capital of the colony, modern Antigua Guatemala, following the Motagua Valley into the highlands. Indigenous guides scouting the route from the highlands would not proceed further downriver than three leagues below Quiriguá because the area was the territory of the hostile Toquegua.[134]

The leaders of Xocolo and Amatique, backed by the threat of Spanish action, persuaded a community of 190 Toquegua to settle on the Amatique coast in April 1604. The new settlement immediately suffered a drop in population and although they were reported extinct before 1613 in some sources, Mercedarian friars were still attending to Amatique Toquegua in 1625.[135] In 1628 the towns of the Manche Ch'ol were placed under the administration of the governor of Verapaz with Francisco Morán as their ecclesiastical head. Morán favoured a more robust approach to the conversion of the Manche and moved Spanish soldiers into the region to protect against raids from the Itza to the north. The new Spanish garrison in an area that had not previously seen a heavy Spanish military presence provoked the Manche to revolt and was followed by abandonment of the indigenous settlements.[136] By 1699 the neighbouring Toquegua no longer existed as a separate people, due to a combination of high mortality and intermarriage with the Amatique Indians.[135] At around this time the Spanish decided upon the reduction of the independent (or "wild" from the Spanish point of view) Mopan Maya living to the north of Lake Izabal.[137] By this time the north shore of the lake, although fertile, was largely depopulated. The Spanish therefore planned to bring the Mopan out of the forests to the north into an area where they could be more easily controlled.[138]

During the same campaign to conquer the Itza of Petén, the Spanish sent expeditions to harrass and relocate the Mopan north of Lake Izabal and the Ch'ol Maya of the Amatique forests to the east. They were resettled in the Colonial reducción of San Antonio de las Bodegas on the south shore of the lake and in San Pedro de Amatique. By the latter half of the 18th century the indigenous population of these towns had disappeared; the local inhabitants now consisted entirely of Spaniards, mulattos and others of mixed race, all associated with the Castillo de San Felipe fort guarding the entrance to Lake Izabal.[138] The main cause of the drastic depopulation of Lake Izabal and the Motagua Delta was the constant slave raids by the Miskito Sambu of the Caribbean coast that effectively ended the Maya population of the region, with captured Maya being sold into slavery in the British colony of Jamaica.[139]

Conquest of Petén

From 1527 onwards the Spanish were increasingly active in the Yucatán Peninsula, establishing a number of colonies and towns by 1544, including Campeche and Valladolid in what is now Mexico.[140] The Spanish impact upon the northern Maya, encompassing invasion, epidemic diseases and the export of up to 50,000 Maya slaves, caused many Maya to flee southwards to join the Itza around Lake Petén Itzá, within the modern borders of Guatemala.[141] The Spanish were aware that the Itza Maya had become the centre of anti-Spanish resistance and engaged in a policy of encircling their kingdom and cutting their trade routes over the course of almost two hundred years. The Itza resisted this steady encroachment by recruiting their neighbours as allies against the slow Spanish advance.[125]

Dominican missionaries were active in Verapaz and the southern Petén from the late 16th century through the 17th century, attempting non-violent conversion with limited success. In the 17th century the Franciscans came to the conclusion that the pacification and Christian conversion of the Maya would not be possible as long as the Itza held out at Lake Petén Itzá. The constant flow of escapees fleeing the Spanish-held territories to find refuge with the Itza was a drain upon the encomiendas.[125] Fray Bartolomé de Fuensalida visited Nojpetén in 1618 and 1619.[142] The Franciscan missionaries attempted to use their own reinterpretation of the k'atun prophecies when they visited Nojpetén at this time, in order to convince the current Aj Kan Ek' and his Maya priesthood that the time for conversion had come.[143] However, the Itza priesthood interpreted the prophecies differently and expressed that the time for conversion had not yet come, and the missionaries were fortunate to escape with their lives.[144] In 1695 the colonial authorities decided to connect the province of Guatemala with Yucatán and Guatemalan soldiers conquered a number of Ch'ol communities, the most important being Sakb'ajlan on the Lacantún River in eastern Chiapas, now in Mexico, which was renamed as Nuestra Señora de Dolores, or Dolores del Lakandon.[144] The Franciscan friar Andrés de Avendaño oversaw a second attempt to overcome the Itza in 1695, convincing the Itza king that the K'atun 8 Ajaw, a twenty-year Maya calendrical cycle beginning in 1696 or 1697, was the right time for the Itza to finally embrace Christianity and to accept the king of Spain as overlord. However the Itza had local Maya enemies who resisted this conversion and in 1696 Avendaño was also fortunate to get away alive.[144] The continued resistance of the Itza had now become a major embarrassment for the Spanish colonial authorities, and soldiers were dispatched from Campeche to take Nojpetén once and for all. The Itza capital fell in a bloody battle on 13 March 1697, after which the surviving defenders melted away into the forests, leaving the Spanish to occupy an abandoned Maya town.[144] In the late 17th century the small population of Ch'ol Maya in southern Petén and Belize were forcibly removed to Alta Verapaz where they were absorbed into the Q'eqchi' population. The Ch'ol of the Lacandon Jungle were resettled in Huehuetenango in the early 18th century.[145]

Legacy of the Spanish conquest

The initial shock of the Spanish conquest was followed by decades of heavy exploitation of the indigenous peoples, for allies and foes alike.[146] Over the following two hundred years colonial rule gradually imposed Spanish cultural standards upon the subjugated peoples. The Spanish reducciones created new nucleated settlements laid out on a grid pattern in the Spanish style, with a central plaza, a church and the town hall housing the civil government, known as the ayuntamiento. This style of settlement can still be seen in the villages and towns of the area. The civil government was either run directly by the Spanish and their descendents (the ladinos) or was closely controlled by them.[48] The introduction of Catholicism was the main means of cultural change, and resulted in religious syncretism.[147] Old World cultural elements came to be thoroughly adopted by Maya groups, an example being the marimba, a musical instrument of African origin.[148] The greatest change was the sweeping aside of the pre-Columbian economic order and its replacement by European technology and livestock; this included the introduction of iron and steel tools to replace Neolithic tools, and of cattle, pigs and chickens that largely replaced the consumption of game. New crops were also introduced but sugarcane and coffee led to the plantations that came to economically exploit native labour.[149] Sixty percent of the modern population of Guatemala is estimated to be Maya, concentrated in the central and western highlands. The eastern portion of the country was the object of intense Spanish migration and hispanicization.[148] Guatemalan society is divided into a class system largely based on race, with Maya peasants and artisans at the bottom, with the mixed-race Ladino salaried workers and bureaucrats forming the middle and lower class and above them the creole elite of pure European ancestry.[150] Some indigenous elites did manage to maintain a level of status into the colonial period, an example being a prominent Kaqchikel noble family, the Xajil, who chronicled the history of their region.[151]

Notes

- ^ Recinos places all these dates 2 days earlier (e.g. the Spanish arrival at Iximche on 12 April rather than 14 April) based on vague dating in Spanish primary records. Schele and Fahsen calculated all dates on the more securely dated Kaqchikel annals, where equivalent dates are often given in both the Kaqchikel and Spanish calendars. The Schele and Fahsen dates are used in this section. Schele & Mathews 1999, p.386.n15.

- ^ Recinos 1998, p.19. gives sixty deserters.

- ^ The location of the historical city of Mixco Viejo has been the source of some confusion. The archaeological site now known as Mixco Viejo has been proven to be Jilotepeque Viejo, the capital of the Chajoma. The Mixco Viejo of colonial records has now been associated with the archaeological site of Chinautla Viejo, much closer to modern Mixco. Carmack 2001a, pp.151, 158.

Citations

- ^ a b Jones 2000, p.356.

- ^ Jones 2000, pp.356-358.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.8.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.757.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.23.

- ^ a b Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.49.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, pp.49-50.

- ^ Díaz del Castillo 1632, 2005, p.5.

- ^ Cortés 1844, 2005, p.xxi.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.50.

- ^ de Las Casas 1552, 1997, p.13.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, pp.79-81.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.94.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, pp.103-104.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.111.

- ^ Lara Figueroa 2000, p.1.

- ^ Polo Sifontes 1986, p.14.

- ^ Hill 1998, pp.229, 233.

- ^ a b Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.6.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.25.

- ^ Polo Sifontes 1981, p.123.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.26. Jiménez 2006, p.1.n.1.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.4.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.717.

- ^ a b Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.5.

- ^ Rice 2009, p.17.

- ^ Rice and Rice 2009, p.10. Rice 2009, p.17.

- ^ Rice 2009, p.17. Feldman 2000, p.xxi.

- ^ Rice 2009, p.19.

- ^ Feldman 2000, p.xxi.

- ^ Rice et al 2009, p.129.

- ^ a b c d Letona Zuleta et al, p.5.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, pp.73, 198.

- ^ Polo Sifontes 1986, pp.57-58.

- ^ a b Polo Sifontes 1986, p.62.

- ^ Polo Sifontes 1986, p.61. Recinos 1952, 1986, p.124.

- ^ Polo Sifontes 1986, p.61.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.761. Díaz del Castillo 1632, 2005, p.10. Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.8.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, pp.15, 61.

- ^ a b Drew 1999, p.382.

- ^ Webster 2002, p.77.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.15.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.16.

- ^ a b c d Hinz 2008, 2010, p.36.

- ^ Jones 2000, p.363.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp.762-763.

- ^ a b Coe 1999, p.231.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.3.

- ^ Carmack 2001b, p.172.

- ^ Hinz 2008, 2010, p.37.

- ^ Jones 2000, p.364.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.763. Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.3.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp.763-764.

- ^ Carmack 2001a, pp.39-40.

- ^ Recinos 1952, 1986, p.65. Gall 1967, pp.40-41.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.764. Gall 1967, p.41.

- ^ Gall 1967, pp.41-42. Díaz del Castillo 1632, 2005, p.510.

- ^ a b Restall and Asselbergs 2007, pp.9, 30.

- ^ Cornejo Sam 2009, pp.269-270.

- ^ Gall 1967, p.41.

- ^ Fuentes y Guzmán 1882, p.49.

- ^ Sharer & Traxler 2006, pp.764-765. Recinos 1952, 1986, pp.68, 74.

- ^ Recinos 1952, 1986, p.74.

- ^ Recinos 1952, 1986, p.75. Sharer & Traxler 2006, pp.764-765.

- ^ a b Recinos 1952, 1986, p.75.

- ^ Recinos 1952, 1986, pp.74-5. Sharer & Traxler 2006, pp.764-765.

- ^ Schele & Mathews 1999, p.297. Guillemín 1965, p.9.

- ^ a b Schele and Mathews 1999, p.297.

- ^ a b Schele & Mathews 1999, p.297. Recinos 1998, p.101. Guillemín 1965, p.10.

- ^ Schelle & Mathews 1999, p.292.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.765. Recinos 1952, 1986, p.82.

- ^ a b c Recinos 1952, 1986, p.82.

- ^ Recinos 1952, 1986, pp.82-83.

- ^ a b c d Recinos 1952, 1986, p.83.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp.765-766. Recinos 1952, 1986, p.84.

- ^ Recinos 1952, 1986, p.84.

- ^ a b c d e Schele & Mathews 1999, p.298.

- ^ Guillemin 1967 p.25.

- ^ Schele & Mathews 1999, pp.298, 310, 386n19.

- ^ a b Schele & Mathews 1999, p.298. Recinos 1998, p.19.

- ^ a b Schele & Mathews 1999, p.299.

- ^ Lutz 1997, pp.10, 258. Ortiz Flores 2008.

- ^ Polo Sifontes 1986, p.92.

- ^ del Águila Flores 2007, p.37.

- ^ a b c Recinos 1986, p.110.

- ^ Polo Sifontes, undated.

- ^ a b Carmack 2001a, p.39.

- ^ del Águila Flores 2007, p.38.

- ^ a b Lehmann 1968, pp.11-13.

- ^ Lehmann 1968, pp.11-13. Recinos, Adrian 1952, 1986, p.108.

- ^ a b Hill 1998, pp.253.

- ^ a b Hill 1996, p.85.

- ^ Carmack 2001a, pp.155-6.

- ^ Hill 1996, pp.65, 67.

- ^ Limón Aguirre 2008, p.10.

- ^ Limón Aguirre 2008, p.11.

- ^ a b INFORPRESSCA 2011. MINEDUC 2001, pp.14-15. Limón Aguirre 2008, p.10.

- ^ Limón Aguirre 2008, pp.10-11.

- ^ a b c d e Lovell 2000, pp.416-417.

- ^ Pons Sáez 1997, pp.149-150.

- ^ Pons Sáez 1997, pp.xxxiii,153-154.

- ^ Pons Sáez 1997, p.154.

- ^ Pons Sáez 1997, pp.154-155.

- ^ a b c Pons Sáez 1997, p.156.

- ^ Pons Sáez 1997, pp.156, 160.

- ^ Pons Sáez 1997, pp.xxxiii.

- ^ a b c Pons Sáez 1997, p.xxxiv.

- ^ Pons Sáez 1997, p.xxxiii.

- ^ Fox 1981, p.321.

- ^ Polo Sifontes 1981, p.111.

- ^ Polo Sifontes 1981, p.113.

- ^ Polo Sifontes 1981, p.114.

- ^ Fox 1981, p.326.

- ^ Fowler 1985, p.41. Recinos 1998, p.29.

- ^ a b Polo Sifontes 1981, p.117.

- ^ Batres 2009, p.65.

- ^ Batres 2009, p.66.

- ^ Letona Zuleta et al, p.6.

- ^ Batres 2009, p.84.

- ^ Rice and Rice 2009, p.5.

- ^ a b c Jones 2000, p.361.

- ^ a b Jones 2000, p.358.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.761.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p.762. Jones 2000, p.358.

- ^ a b Feldman 1998, p.6.

- ^ Webster 2002, p.83.

- ^ a b Feldman 1998, p.7.

- ^ Feldman 1998, p.8.

- ^ a b Feldman 1998, p.10.

- ^ Feldman 2000, p.xxii.

- ^ Feldman 1998, pp.10-11.

- ^ a b Feldman 1998, p.11.

- ^ Feldman 1998, p.12.

- ^ Jones 2000, pp.358-360.

- ^ Jones 2000, pp.360-361.

- ^ Rice and Rice 2009, p.11.

- ^ Jones 2000, pp.361-362.

- ^ a b c d Jones 2000, p.362.

- ^ Jones 2000, p.365.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.111.

- ^ Coe 1999, pp.231-232.

- ^ a b Coe 1999, p.233.

- ^ Coe 1999, p.232.

- ^ Smith 1997, p.60.

- ^ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p.104.

References

- Batres, Carlos A. (2009). "Tracing the "Enigmatic" Late Postclassic Nahua-Pipil (A.D. 1200-1500): Archaeological Study of Guatemalan South Pacific Coast". Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

{{cite web}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Carmack, Robert M. (2001a). Kik'aslemaal le K'iche'aab': Historia Social de los K'iche's. Guatemala: Iximulew. ISBN 99922-56-19-2. OCLC 47220876.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Carmack, Robert M. (2001b). Kik'ulmatajem le K'iche'aab': Evolución del Reino K'iche'. Guatemala: Iximulew. ISBN 99922-56-22-2. OCLC 253481949.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Coe, Michael D. (1999). The Maya. Ancient peoples and places series (6th edition, fully revised and expanded ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28066-5. OCLC 59432778.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Cornejo Sam, Mariano. Q'antel (Cantel): Patrimonio cultural-histórico del pueblo de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción Cantel: Tzion'elil echba'l kech aj kntelab "Tierra de Viento y Neblina". Quetzaltenango, Guatemala.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Cortés, Hernán (1844, 2005). Manuel Alcalá (ed.). Cartas de Relación. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa. ISBN 970-07-5830-3. OCLC 229414632.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) Template:Es icon - de Las Casas, Bartolomé (1552, 1997). Olga Camps (ed.). Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias. Mexico City: Distribuciones Fontamara, S.A. ISBN 968-476-013-2. OCLC 32265767.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) Template:Es icon - del Águila Flores, Patricia (2007). "Zaculeu: Ciudad Postclásica en las Tierras Altas Mayas de Guatemala" (PDF). Guatemala: Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

{{cite web}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Díaz del Castillo, Bernal (1632, 2005). Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. Mexico City: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, S.A. ISBN 968-15-0863-7. OCLC 34997012.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) Template:Es icon - Drew, David (1999). The Lost Chronicles of the Maya Kings. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81699-3. OCLC 43401096.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Feldman, Lawrence H. (1998). Motagua Colonial. Raleigh, North Carolina: Boson Books. ISBN 1-886420-51-3. OCLC 82561350.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Feldman, Lawrence H. (2000). Lost Shores, Forgotten Peoples: Spanish Explorations of the South East Maya Lowlands. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2624-8. OCLC 254438823.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Fowler, William R. Jr. (1985). "Ethnohistoric Sources on the Pipil-Nicarao of Central America: A Critical Analysis". Ethnohistory. 32 (1). Duke University Press: 37–62. ISSN 0014-1801. OCLC 478130795. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Fox, John W. (1981). "The Late Postclassic Eastern Frontier of Mesoamerica: Cultural Innovation Along the Periphery". Current Anthropology. 22 (4). The University of Chicago Press on behalf of Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research: 321–346. ISSN 0011-3204. OCLC 4644864425. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Fuentes y Guzman, Francisco Antonio de (1882). Luis Navarro (ed.). Historia de Guatemala o Recordación Florida. Vol. I. Madrid: Biblioteca de los Americanistas. OCLC 699103660.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthor=at position 6 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Gall, Francis (1967). "Los Gonzalo de Alvarado, Conquistadores de Guatemala". Anales de la Sociedad de Geografía e Historia. XL. Guatemala City: Sociedad de Geografía e Historia de Guatemala. OCLC 72773975.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Guillemín, Jorge F. (1965). Iximché: Capital del Antiguo Reino Cakchiquel. Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional de Guatemala. OCLC 1498320.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Guillemin, George F. (1967). "The Ancient Cakchiquel Capital of Iximche" (PDF). Expedition. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: pp.22–35. ISSN 0014-4738. OCLC 1568625. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Hill, Robert M. II (1996). "Eastern Chajoma (Cakchiquel) Political Geography: Ethnohistorical and archaeological contributions to the study of a Late Postclassic highland Maya polity". Ancient Mesoamerica. 7. New York: Cambridge University Press: pp.63–87. ISSN 0956-5361. OCLC 88113844.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Hill, Robert M. II (1998). "Los Otros Kaqchikeles: Los Chajomá Vinak". Mesoamérica. 35. Antigua Guatemala: El Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica (CIRMA) in conjunction with Plumsock Mesoamerican Studies, South Woodstock, VT: 229–254. ISSN 0252-9963. OCLC 7141215.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Hinz, Eike (2008, 2010). "Existence and Identity: Reconciliation and Self-organization through Q'anjob'al Maya Divination" (PDF). Hamburg and Norderstedt: Universität Hamburg. ISBN 9783833487316. OCLC 299685808. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - INFORPRESSCA (2011). "Reseña Historia del Municipio de San Mateo Ixtatán, Huehuetenango". Guatemala. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Jiménez, Ajb’ee (2006). "Qnaab'ila b'ix Qna'b'ila, Our thoughts and our feelings: Maya-Mam women's struggles in San Ildefonso Ixtahuacán" (PDF). University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 2011-09-04.

{{cite web}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Jones, Grant D. (2000). "The Lowland Maya, from the Conquest to the Present". In Richard E.W. Adams and Murdo J. Macleod (eds.) (ed.). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 346–391. ISBN 0-521-65204-9. OCLC 33359444.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Lara Figueroa, Celso A. (2000). "Introducción". Recordación Florida: Primera Parte: Libros Primero y Segundo. Ayer y Hoy (3rd ed.). Guatemala: Editorial Artemis-Edinter. ISBN 84-89452-66-0.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Lehmann, Henri (1968). Guide to the Ruins of Mixco Viejo. Andrew McIntyre and Edwin Kuh. Guatemala: Piedra Santa. OCLC 716195862.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|others=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Letona Zuleta, José Vinicio. "Las tierras comunales xincas de Guatemala". In Carlos Camacho Nassar (ed.). Tierra, identidad y conflicto en Guatemala (DOC). Guatemala: Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO; Misión de Verificación de las Naciones Unidas en Guatemala (MINUGUA); Dependencia Presidencial de Asistencia Legal y Resolución de Conflictos sobre la Tierra (CONTIERRA). ISBN 9789992266847. OCLC 54679387. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Limón Aguirre, Fernando (2008). "La ciudadanía del pueblo chuj en México: Una dialéctica negativa de identidades" (PDF). San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Mexico: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur – Unidad San Cristóbal de Las Casas. Retrieved 2011-09-15.

{{cite web}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Lovell, W. George (2000). "The Highland Maya". In Richard E.W. Adams and Murdo J. Macleod (eds.) (ed.). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 392–444. ISBN 0-521-65204-9. OCLC 33359444.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Lutz, Christopher H. (1997). Santiago de Guatemala, 1541-1773: City, Caste, and the Colonial Experience. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806125977. OCLC 29548140.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - MINEDUC (2001). Eleuterio Cahuec del Valle (ed.). Historia y Memorias de la Comunidad Étnica Chuj. Vol. II (Versión escolar ed.). Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar/UNICEF/FODIGUA. OCLC 741355513. Template:Es icon

- Ortiz Flores, Walter Agustin (2008). "Segundo Asiento Oficial de la Ciudad según Acta". Ciudad Vieja Sacatepéquez, Guatemala: www.miciudadvieja.com. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

{{cite web}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Polo Sifontes, Francis (1981). Francis Polo Sifontes and Celso A. Lara Figueroa (ed.). "Título de Alotenango, 1565: Clave para ubicar geograficamente la antigua Itzcuintepec pipil". Antropología e Historia de Guatemala. 3, II Epoca. Guatemala: Dirección General de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala, Ministerio de Educación: 109–129. OCLC 605015816.

{{cite journal}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Polo Sifontes, Francis (1986). Los Cakchiqueles en la Conquista de Guatemala. Guatemala: CENALTEX. OCLC 82712257.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Polo Sifontes, Francis (unknown). Zaculeu: Ciudadela Prehispánica Fortificada. Guatemala: IDAEH (Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala).

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) Template:Es icon - Pons Sáez, Nuria (1997). La Conquista del Lacandón. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ISBN 968-36-6150-5. OCLC 40857165.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Recinos, Adrian (1952, 1986). Pedro de Alvarado: Conquistador de México y Guatemala (2nd ed.). Guatemala: CENALTEX Centro Nacional de Libros de Texto y Material Didáctico "José de Pineda Ibarra". OCLC 243309954.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) Template:Es icon - Recinos, Adrian (1998). Memorial de Solalá, Anales de los Kaqchikeles; Título de los Señores de Totonicapán. Guatemala: Piedra Santa. ISBN 84-8377-006-7. OCLC 25476196.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Restall, Matthew (2007). Invading Guatemala: Spanish, Nahua, and Maya Accounts of the Conquest Wars. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02758-6. OCLC 165478850.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 5 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Rice, Prudence M. (2009). "Who were the Kowoj?". In Pridence M. Rice and Don S. Rice (eds.) (ed.). The Kowoj: identity, migration, and geopolitics in late postclassic Petén, Guatemala. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-87081-930-8. OCLC 225875268.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Rice, Prudence M. (2009). "Introduction to the Kowoj and their Petén Neighbors". In Pridence M. Rice and Don S. Rice (eds.) (ed.). The Kowoj: identity, migration, and geopolitics in late postclassic Petén, Guatemala. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 3–15. ISBN 978-0-87081-930-8. OCLC 225875268.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 5 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Rice, Prudence M. (2009). "Defensive Architecture and the Context of Warfare at Zacpetén". In Pridence M. Rice and Don S. Rice (eds.) (ed.). The Kowoj: identity, migration, and geopolitics in late postclassic Petén, Guatemala. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 123–140. ISBN 978-0-87081-930-8. OCLC 225875268.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Schele, Linda (1999). The Code of Kings: The language of seven Maya temples and tombs. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-85209-6. OCLC 41423034.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 5 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Sharer, Robert J. (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|coauthors=at position 6 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Smith, Carol A. (1997). "Race/Class/Gender Ideology in Guatemala: Modern and Anti-Modern Forms". In Brackette Williams (ed.). Women Out of Place: The Gender of Agency, the Race of Nationality. New York and London: Routledge. pp. 50–78. ISBN 0-415-91496-5. OCLC 60185223.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Webster, David L. (2002). The Fall of the Ancient Maya: Solving the Mystery of the Maya Collapse. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05113-5. OCLC 48753878.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)