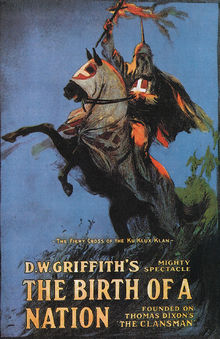

The Birth of a Nation

| The Birth of a Nation | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | D. W. Griffith |

| Written by | D. W. Griffith, T. F. Dixon, Jr. Frank E. Woods |

| Produced by | D. W. Griffith, Harry Aitken[1] |

| Starring | Lillian Gish Mae Marsh Henry B. Walthall Miriam Cooper Ralph Lewis George Siegmann |

| Cinematography | G.W. Bitzer |

| Edited by | D. W. Griffith |

| Music by | Joseph Carl Breil |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Epoch Producing Co. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 190 minutes (at 16 frame/s) |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | Silent film English intertitles |

| Budget | $110,000 (est.) |

| Box office | $50,000,000[2] |

The Birth of a Nation (originally called The Clansman) is a 1915 silent drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and based on the novel and play The Clansman, both by Thomas Dixon, Jr. Griffith co-wrote the screenplay (with Frank E. Woods), and co-produced the film (with Harry Aitken). It was released on February 8, 1915. The film was originally presented in two parts, separated by an intermission.

The film chronicles the relationship of two families in Civil War and Reconstruction-era America: the pro-Union Northern Stonemans and the pro-Confederacy Southern Camerons over the course of several years. The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth is dramatized.

The film was a commercial success, but was highly controversial owing to its portrayal of African American men (played by white actors in blackface) as unintelligent and sexually aggressive towards white women, and the portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan (whose original founding is dramatized) as a heroic force.[3][4] There were widespread protests[5] against The Birth of a Nation, and the outcry of racism was so great that Griffith was inspired to produce Intolerance the following year.[6] In addition, some cities had it banned.

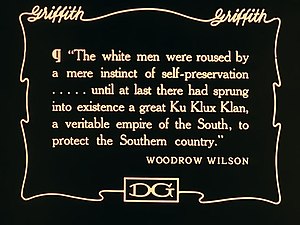

The movie is also credited as one of the events that inspired the formation of the "second era" Ku Klux Klan at Stone Mountain, Georgia in the same year. The Birth of a Nation was used as a recruiting tool for the KKK.[7] It was the first motion picture to be shown at the White House. President Woodrow Wilson supposedly said the film was "like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true." The attribution is disputed.

Plot

Part 1: Pre-Civil War America

The film follows two juxtaposed families: the Northern Stonemans, consisting of the abolitionist Congressman Austin Stoneman (based on the Reconstruction-era Congressman Thaddeus Stevens[citation needed]), his two sons, and his daughter Elsie; and the Southern Camerons, a family including two daughters, Margaret and Flora, and three sons, most notably Ben.

The Stoneman brothers visit the Camerons at their South Carolina estate, representing the Old South. The elder of the two Stoneman sons falls in love with Margaret Cameron, while Ben Cameron idolizes a picture of Elsie Stoneman. When the Civil War begins, all the young men join their respective armies.

A black militia (with a white leader) ransacks the Cameron house. The Cameron women are rescued when Confederate soldiers rout the militia. Meanwhile, the younger Stoneman and two of the Cameron brothers are killed in the war. Ben Cameron is wounded after a heroic charge at the Siege of Petersburg, in which he gains the nickname "the Little Colonel". He is taken to a Northern hospital where he meets Elsie Stoneman, who is working there as a nurse. While recovering, Cameron is told that he will be hanged for being a guerrilla. Elsie takes Cameron's mother, who has traveled to Washington to tend her son, to see Abraham Lincoln. Mrs. Cameron persuades Lincoln to issue a pardon.

When Lincoln is assassinated at Ford's Theater, his conciliatory postwar policy expires with him. Austin Stoneman and other radical congressmen are determined to punish the South, using harsh measures that Griffith depicts as typical of the Reconstruction era.[8]

Part 2: Reconstruction

Stoneman and his mulatto protégé, Silas Lynch, go to South Carolina in 1871 to observe the situation first hand. Black soldiers parade through the streets. During the election, whites are turned away while blacks stuff the ballot boxes. Lynch is elected Lieutenant Governor. The newly-elected mostly-black legislature is shown at their desks, with one member taking off his shoe and putting his feet up, and others drinking liquor and feasting. They pass laws requiring white civilians to salute black officers and allowing mixed-race marriages.

Meanwhile, inspired by observing white children pretending to be ghosts to scare off black children, Ben fights back by forming the Ku Klux Klan. As a result, Elsie breaks off their relationship out of loyalty to her father. Gus, a freedman and soldier who is now a Captain, follows Flora Cameron as she goes alone to fetch water. He tells her he is looking to get married. Frightened, she flees into the forest, pursued by Gus. Trapped on a precipice, Flora warns Gus she will jump if he comes any closer. When he does, she leaps to her death. Ben finds his sister, having run through the Forest looking for her and seen her jump, and holds her as she lies dying. The Klan hunts Gus down, tries him, and finds him guilty. The clansmen leave his corpse on Lynch's doorstep.

Lynch orders a crackdown on the Klan. Dr. Cameron, Ben's father, is arrested for having Ben's Klan costume, a crime punishable by death. Ben and their faithful servants rescue him, and the Camerons flee. When their wagon breaks down, they make their way to a small hut, home to two former Union soldiers, who agree to hide them. As an intertitle states, "The former enemies of North and South are united again in defense of their Aryan birthright."

Austin Stoneman leaves to avoid being connected with Lynch's crackdown. Elsie, learning of Dr. Cameron's arrest, goes to Lynch to plead for his release. Lynch tries to force Elsie to marry him and she finally faints. Stoneman returns, causing Elsie to be placed in another room, and is happy at first when Lynch tells him he wants to marry a white woman, but is angered when Lynch tells him which one. Disguised Klansmen spies discover Elsie's plight when she breaks a window and cries for help and leave to get help. She falls unconscious again, and revives gagged and being bound. The Klan, gathered together at full strength and with Ben leading them, rides in to regain control of the town. When news reaches Ben about Elsie, he and others go to her rescue. Elsie frees her mouth and screams for help. Lynch is captured. Victorious, the clansmen celebrate in the streets. Meanwhile, Lynch's militia surrounds and attacks the hut where the Camerons are hiding. The clansmen, with Ben at their head, race to save them just in time.

The next election day, blacks find a line of mounted and armed Klansmen just outside their homes, and are intimidated into not voting. The film concludes with a double honeymoon of Phil Stoneman with Margaret Cameron and Ben Cameron with Elsie Stoneman. The masses are shown oppressed by a giant warlike figure who gradually fades away. The scene shifts to another group finding peace under the image of Christ. The penultimate title rhetorically asks: "Dare we dream of a golden day when the bestial War shall rule no more? But instead-the gentle Prince in the Hall of Brotherly Love in the City of Peace."

Cast

|

Uncredited:

|

Production

The Birth of a Nation began filming in 1914 and pioneered such camera techniques as the use of panoramic long shots, the iris effects, still-shots, night photography, panning camera shots, and a carefully staged battle sequence with hundreds of extras made to look like thousands. It also contains many new artistic techniques, such as color tinting for dramatic purposes, building up the plot to an exciting climax, dramatizing history alongside fiction, and featuring its own musical score written for an orchestra.[citation needed]

When the film was released, it shattered both box office and film-length records, running three hours and ten minutes. Its power continues to be recognized. In 1998, it was voted one of the "Top 100 American Films" (#44) by the American Film Institute.

The film was based on Thomas Dixon, Jr.'s novels The Clansman and The Leopard's Spots. It was originally to have been shot in Kinemacolor but D. W. Griffith took over the Hollywood studio of Kimemacolor and Kinemacolor's plans to film Dixon's novel. Griffith, whose father served as a colonel in the Confederate Army, agreed to pay Thomas Dixon $10,000 (equal to $304,186 today) for the rights to his play The Clansman. Since he ran out of money and could afford only $2,500 of the original option, Griffith offered Dixon 25 percent interest in the picture. Dixon reluctantly agreed, and the unprecedented success of the film made him rich. Dixon's proceeds were the largest sum any author had received for a motion picture story and amounted to several million dollars.[citation needed]

Griffith's budget started at US$40,000 (equal to $1,216,744 today), but the film finally cost $112,000[9] (the equivalent of $2.41 million in 2010).[10] As a result, Griffith had to seek new sources of capital for his film. A ticket to the film cost a record $2 (equal to $60.24 today).[10]

West Point engineers provided technical advice on the Civil War battle scenes. They provided Griffith with the artillery used in the film.[11]

The film premiered on February 8, 1915, at Clune's Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles. At its premiere the film was entitled The Clansman, but the title was later changed to The Birth of a Nation to reflect Griffith's belief that the United States emerged out of the American Civil War and Reconstruction as a unified nation.[12]

The film is in the public domain.[13]

Responses

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, protested premieres of the film in numerous cities. It also conducted a public education campaign, publishing articles protesting the film's fabrications and inaccuracies, organizing petitions against it, and conducting education on the facts of the war and Reconstruction.[14]

When the film was shown, riots broke out in Boston, Philadelphia and other major cities. The cities of Chicago; Denver; Kansas City, Missouri; Minneapolis; Pittsburgh; and St. Louis, Missouri, refused to allow the film to open. The film's inflammatory character was a catalyst for gangs of whites to attack blacks. In Template:USCity, after seeing the film, a white man murdered a black teenager.[15]

Thomas Dixon, Jr., author of the source play The Clansman, was a former classmate of Woodrow Wilson at Johns Hopkins University. Dixon arranged a screening at the White House, for then-President Wilson, members of his cabinet, and their families. Wilson was reported to have said about the film, "It is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true". In Wilson: The New Freedom, the historian Arthur Link quotes Wilson's aide, Joseph Tumulty, who denied Wilson said this and also claims that "the President was entirely unaware of the nature of the play before it was presented and at no time has expressed his approbation of it."[16] Historians believe the quote attributed to Wilson originated with Dixon, who was relentless in publicizing the film. It has been repeated so often in print that it has taken on a life of its own. Dixon went so far as to promote the film as "Federally endorsed". After controversy over the film had grown, Wilson wrote that he disapproved of the "unfortunate production."[17]

Griffith responded to the film's negative critical reception with his next film, Intolerance.

Soon after World War I, in 1918, Emmett J. Scott helped produce and John W. Noble directed The Birth of a Race, hoping to capitalize on the success of Griffith's film by presenting a film set during the war. It featured a German-American family divided by the war, with sons fighting on either side, and the one loyal to the United States surviving to be part of the victory.[18]

In 1919, the director/producer/writer Oscar Micheaux released Within Our Gates, a response from the African-American community. Notably, he reversed a key scene of Griffith's film by depicting a white man assaulting a black woman.

The film was remixed as Rebirth of a Nation, a "live" cinema experience by DJ Spooky at Lincoln Center, and has toured at many venues around the world including The Acropolis as a live cinema "remix". The remix version was also presented at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York[19]

Ideology and accuracy

The film is controversial due to its interpretation of history. University of Houston historian Steven Mintz summarizes its message as follows: Reconstruction was a disaster, blacks could never be integrated into white society as equals, and the violent actions of the Ku Klux Klan were justified to reestablish honest government.[20] The film suggested that the Ku Klux Klan restored order to the post-war South, which was depicted as endangered by abolitionists, freedmen, and carpetbagging Republican politicians from the North. This reflects the so-called Dunning School of historiography.[21]

W. E. B. Du Bois and other black historians vigorously disputed this interpretation[clarification needed] when the film was released. Most historians of all backgrounds today agree with Du Bois[citation needed], as they note African Americans' loyalty and contributions during the Civil War years and Reconstruction, including the establishment of universal public education. Some historians, such as E. Merton Coulter in his The South Under Reconstruction (1947), maintained the Dunning School view after World War II. Today, the Dunning School position is largely seen as a product of anti-black racism of the early 20th century, by which many Americans held that black Americans were unequal as citizens.

Veteran film reviewer Roger Ebert wrote,

... stung by criticisms that the second half of his masterpiece was racist in its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan and its brutal images of blacks, Griffith tried to make amends in Intolerance (1916), which criticized prejudice. And in Broken Blossoms he told perhaps the first interracial love story in the movies—even though, to be sure, it's an idealized love with no touching.[22]

Despite some similarities between the Congressman Stoneman character and Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, Rep. Stevens did not have the family members described and did not move to South Carolina during Reconstruction. He died in Washington, DC in 1868. However, Stevens was widely rumored to keep a mulatto mistress-housekeeper, who was generously provided for in his will.[23]

The depictions of mass Klan paramilitary actions do not seem to have historical equivalents, although there were incidents in 1871 where Klan groups traveled from other areas in fairly large numbers to aid localities in disarming local companies of the all-black portion of the state militia under various justifications prior to the eventual Federal troop intervention and the organized Klan's continued activities as small groups of "night riders".[24]

The civil rights movement and other social movements created a new generation of historians, such as scholar Eric Foner, who led a reassessment of Reconstruction. Building on Du Bois' work but also adding new sources, they focused on achievements of the African American and white Republican coalitions, such as establishment of universal public education and charitable institutions in the South and extension of suffrage to black men. In response, the Southern-dominated Democratic Party and its affiliated white militias used extensive terrorism, intimidation and outright assassinations to suppress African-American leaders and voting in the 1870s and to regain power.[25]

Significance

Released in 1915, The Birth of a Nation has been credited as groundbreaking among its contemporaries for its innovative application of the medium of film. The content of the work, however, has received widespread criticism for its blatantly racist and fantastical depictions of scenes that are presented onscreen as if in documentary form. Film critic Roger Ebert writes, "Certainly The Birth of a Nation (1915) presents a challenge for modern audiences. Unaccustomed to silent films and uninterested in film history, they find it quaint and not to their taste. Those evolved enough to understand what they are looking at find the early and wartime scenes brilliant, but cringe during the postwar and Reconstruction scenes, which are racist in the ham-handed way of an old minstrel show or a vile comic pamphlet."[26]

The film earned $10 million in its initial release, and over the next 35 years increased its total to $50 million,[2] holding the mantle of the highest grossing film until it was overtaken by Gone with the Wind.[27]

In 1992, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry. Despite its controversial story, the film has been praised by film critics such as Roger Ebert, who said: "The Birth of a Nation is not a bad film because it argues for evil. Like Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, it is a great film that argues for evil. To understand how it does so is to learn a great deal about film, and even something about evil."[26] The website Rotten Tomatoes, which compiles reviews from various sources, indicates the film has a 100% "fresh" (positive) rating.[28]

According to a 2002 article in the Los Angeles Times, the film facilitated the refounding of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.[29] As late as the 1970s, the Ku Klux Klan continued to use the film as a recruitment tool.

American Film Institute recognition

Sequel

A sequel called The Fall of a Nation was released in 1916. The film was directed by Thomas Dixon, Jr., who adapted it from his own novel The Fall of a Nation. The film has three acts and a prologue.[30] Despite its success in the foreign market, the film was not a success among the American audiences.[31] It is believed that it is now a lost film.

New opening titles on re-release

One famous part of the film was added by Griffith only on the second run of the film[32] and is missing from most online versions of the film (presumably taken from first run prints.)[33]

These are the second and third of three opening title cards which defend the film. The added titles read:

A PLEA FOR THE ART OF THE MOTION PICTURE: We do not fear censorship, for we have no wish to offend with improprieties or obscenities, but we do demand, as a right, the liberty to show the dark side of wrong, that we may illuminate the bright side of virtue – the same liberty that is conceded to the art of the written word – that art to which we owe the Bible and the works of Shakespeare

and

If in this work we have conveyed to the mind the ravages of war to the end that war may be held in abhorrence, this effort will not have been in vain.

Various film historians have expressed a range of views about these titles. To Nicholas Andrew Miller, this shows that "Griffith's greatest achievement in The Birth of Nation was that he brought the cinema's capacity for spectacle...under the rein of an outdated by comfortably literary form of historical narrative. Griffith's models...are not the pioneers of film spectacle...but the giants of literary narrative."[34] On the other hand, S. Kittrell Rushing complains about Griffith's "didactic" title-cards,[35] while Stanley Corkin complains that Griffith "masks his idea of fact in the rhetoric of high art and free expression" and creates film which "erodes the very ideal" of "liberty" which he asserts.[36]

References

- Notes

- ^ D. W. Griffith: Hollywood Independent

- ^ a b Rucker, Walter C.; Upton, James N., eds. (2007). Encyclopedia of American race riots. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-313-33301-9.

...earning more than $10 million at the box office in 1915. By 1949, it had earned $50 million

- ^ MJ Movie Reviews – Birth of a Nation, The (1915) by Dan DeVore [dead link]

- ^ Armstrong, Eric M. (February 26, 2010). "Revered and Reviled: D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation'". The Moving Arts Film Journal. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Mass Moments: “The Birth of a Nation” Sparks Protest

- ^ Top Ten – Top 10 Banned Films of the 20th century – Top 10 – Top 10 List – Top 10 Banned Movies – Censored Movies – Censored Films

- ^ A Birth of a Nation essays

- ^ Griffith followed the then-dominant Dunning School or "Tragic Era" view of Reconstruction presented by early 20th-century historians such as William Archibald Dunning and Claude G. Bowers. Stokes 2007, pp. 190–191.

- ^ William K. Everson, American Silent Film. New York: Da Capo Press, 1978, p. 78

- ^ a b Consumer Price Index calculator at Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis website

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q. "When Hollywood's Big Guns Come Right From the Source", The New York Times, June 10, 2002.

- ^ Dirks, Tim, The Birth of a Nation, filmsite.org Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ^ "Birth of a Nation" at the Internet Archive. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ^ NAACP – Timeline Template:WebCite

- ^ "The Birth of a Nation", The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow: Jim Crow Stories, PBS

- ^ Letter from J. M. Tumulty, secretary to President Wilson, to the Boston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, quoted in Link, Wilson.

- ^ Woodrow Wilson to Joseph P. Tumulty, April 28, 1915 in Wilson, Papers, 33:86.

- ^ [ New York Times. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Rebirth of a Nation at Paula Cooper Gallery

- ^ UG.edu, Digital History.

- ^ Stokes 2007, pp. 190–191.

- ^ SunTimes.com

- ^ Marc Egnal, Clash of Extremes, 2009.

- ^ West, Jerry Lee. The Reconstruction Ku Klux Klan in York County, South Carolina, 1865–1877 (2002) p. 67

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War. New York: Farrar Strauss and Giroux, 2006, p. 150-154

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger. "The Birth of a Nation (1915)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ^ Finler, Joel Waldo (2003). The Hollywood Story. Wallflower Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-903364-66-6.

- ^ "The Birth of a Nation Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hartford-HWP.com, A Painful Present as Historians Confront a Nation's Bloody Past.

- ^ The Fall of a Nation (1916) at IMDb

- ^ Slide, Anthony (2004). American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon. University Press of Kentucky. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8131-2328-8.

- ^ Richard Schickel, D. W. Griffith: An American Life (New York: Limelight Editions, 1984), p. 282

- ^ This includes the one at the Internet Movie Archive [1] and the Google video copy [2] and Veoh Watch Videos Online | The Birth of a Nation | Veoh.com. However, of multiple YouTube copies one which has the full opening titles is DW GRIFFITH THE BIRTH OF A NATION PART 1 1915 – YouTube

- ^ Miller, Nicholas Andrew (2002). Modernism, Ireland and the erotics of memory. Cambridge University Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-521-81583-5, 9780521815833.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Rushing, S. Kittrell (2007). Memory and myth: the Civil War in fiction and film from Uncle Tom's cabin to Cold mountain. Purdue University Press. p. 307. ISBN 1-55753-440-3, 9781557534408.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Corkin, Stanley (1996). Realism and the birth of the modern United States:cinema, literature, and culture. University of Georgia Press. p. 240. ISBN 0-8203-1730-6, 9780820317304.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help)

- Bibliography

- Addams, Jane, in Crisis: A Record of Darker Races, X (May 1915), 19, 41, and (June 1915), 88.

- Bogle, Donald. Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (1973).

- Brodie, Fawn M. Thaddeus Stevens, Scourge of the South (New York, 1959) p. 86–93. Corrects the historical record as to Dixon's false representation of Stevens in this film with regard to his racial views and relations with his housekeeper.

- Chalmers, David M. Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan (New York: 1965) p. 30 *Cook, Raymond Allen. Fire from the Flint: The Amazing Careers of Thomas Dixon (Winston-Salem, N.C., 1968).

- Franklin, John Hope. "Silent Cinema as Historical Mythmaker". In Myth America: A Historical Anthology, Volume II. 1997. Gerster, Patrick, and Cords, Nicholas. (editors.) Brandywine Press, St. James, NY. ISBN 978-1-881089-97-1

- Franklin, John Hope, "Propaganda as History" pp. 10–23 in Race and History: Selected Essays 1938–1988 (Louisiana State University Press: 1989); first published in The Massachusetts Review 1979. Describes the history of the novel, The Clan and this film.

- Franklin, John Hope, Reconstruction After the Civil War, (Chicago, 1961) p. 5–7

- Hodapp, Christopher L., VonKannon, Alice, Conspiracy Theories & Secret Societies For Dummies, (Hoboken: Wiley, 2008) p. 235–6

- Korngold, Ralph, Thaddeus Stevens. A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great (New York: 1955) pp. 72–76. corrects Dixon's false characterization of Stevens' racial views and of his dealings with his housekeeper.

- Leab, Daniel J., From Sambo to Superspade, (Boston, 1975) p. 23–39

- New York Times, roundup of reviews of this film, March 7, 1915.

- The New Republica, II (March 20, 1915), 185

- Poole, W. Scott, Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting, (Waco, Texas: Baylor, 2011), 30. ISBN 978-1-60258-314-6

- Simkins, Francis B., "New Viewpoints of Southern Reconstruction," Journal of Southern History, V (February, 1939), pp. 49–61.

- Stokes, Melvyn, D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation: A History of "The Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time" (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007). The latest study of the film's making and subsequent career.

- Williamson, Joel, After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina During Reconstruction (Chapel Hill, 1965). This book corrects Dixon's false reporting of Reconstruction, as shown in his novel, his play and this film.

External links

- The Birth of a Nation at IMDb

- Birth of a Nation on YouTube

- The Birth of a Nation is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- The Birth of a Nation at the TCM Movie Database

- The Birth of a Nation at AllMovie

- The Birth of a Nation at Rotten Tomatoes

- GMU.edu, "Art (and History) by Lightning Flash": The Birth of a Nation and Black Protest

- The Birth of a Nation on Roger Ebert's list of great movies

- The Birth of a Nation on filmsite.org, a web site offering comprehensive summaries of classic films

- The Myth of a Nation by Greg Ferrara, challenging some of the "firsts" listed by film historians

- Souvenir Guide for The Birth of a Nation, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Virtual-History.com, Literature

- W. Scott Poole, Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (Waco, Texas: Baylor, 2011), 30, 87, 100–101.

- 1915 films

- 1910s drama films

- American films

- American Civil War films

- American drama films

- American silent feature films

- Abraham Lincoln in fiction

- Black-and-white films

- Blackface minstrel shows and films

- Epic films

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Films based on novels

- Films based on plays

- Films directed by D. W. Griffith

- Films set in the 1860s

- Films set in the 1870s

- History of racism in the cinema of the United States

- History of the Southern United States

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- Ku Klux Klan

- White supremacy in the United States

- United States National Film Registry films