Low back pain

| Low back pain | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Orthopedic surgery, rehabilitation |

Low back pain or lumbago (/[invalid input: 'icon']lʌmˈbeɪɡoʊ/) is a common musculoskeletal disorder affecting 80% of people at some point in their lives. In the United States it is the most common cause of job-related disability, a leading contributor to missed work, and the second most common neurological ailment — only headache is more common.[1] It can be either acute, subacute or chronic in duration. With conservative measures, the symptoms of low back pain typically show significant improvement within a few weeks from onset.

Classification

Lower back pain may be classified by the duration of symptoms as acute (less than 4 weeks), sub acute (4–12 weeks), chronic (more than 12 weeks).[2]

Cause

The majority of lower back pain stems from benign musculoskeletal problems, and are referred to as non specific low back pain; this type may be due to muscle or soft tissues sprain or strain,[3] particularly in instances where pain arose suddenly during physical loading of the back, with the pain lateral to the spine. Over 99% of back pain instances fall within this category.[4] The full differential diagnosis includes many other less common conditions.

- Mechanical:

- Apophyseal osteoarthritis

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Degenerative discs

- Scheuermann's kyphosis

- Spinal disc herniation ("slipped disc")

- Thoracic or lumbar spinal stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis and other congenital abnormalities

- Fractures

- Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

- Leg length difference

- Restricted hip motion

- Misaligned pelvis - pelvic obliquity, anteversion or retroversion

- Abnormal Foot Pronation

- Inflammatory:

- Seronegative spondylarthritides (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Infection - epidural abscess or osteomyelitis

- Sacroiliitis

- Neoplastic:

- Bone tumors (primary or metastatic)

- Intradural spinal tumors

- Metabolic:

- Osteoporotic fractures

- Osteomalacia

- Ochronosis

- Chondrocalcinosis

- Referred pain:

- Pelvic/abdominal disease

- Prostate Cancer

- Posture

Pathophysiology

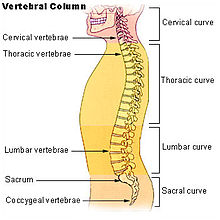

The lumbar region (or lower back region) is made up of five vertebrae (L1-L5). In between these vertebrae lie fibrocartilage discs (intervertebral discs), which act as cushions, preventing the vertebrae from rubbing together while at the same time protecting the spinal cord. Nerves stem from the spinal cord through foramina within the vertebrae, providing muscles with sensations and motor associated messages. Stability of the spine is provided through ligaments and muscles of the back, lower back and abdomen. Small joints which prevent, as well as direct, motion of the spine are called facet joints (zygapophysial joints).[6]

Causes of lower back pain are varied. Most cases are believed to be due to a sprain or strain in the muscles and soft tissues of the back.[3] Overactivity of the muscles of the back can lead to an injured or torn ligament in the back which in turn leads to pain. An injury can also occur to one of the intervertebral discs (disc tear, disc herniation). Due to aging, discs begin to diminish and shrink in size, resulting in vertebrae and facet joints rubbing against one another. Ligament and joint functionality also diminishes as one ages, leading to spondylolisthesis, which causes the vertebrae to move much more than they should. Pain is also generated through lumbar spinal stenosis, sciatica and scoliosis. At the lowest end of the spine, some patients may have tailbone pain (also called coccyx pain or coccydynia). Others may have pain from their sacroiliac joint, where the spinal column attaches to the pelvis, called sacroiliac joint dysfunction which may be responsible for 22.6% of low back pain.[7] Physical causes may include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, degeneration of the discs between the vertebrae or a spinal disc herniation, a vertebral fracture (such as from osteoporosis), or rarely, an infection or tumor[8] .

In the vast majority of cases, no noteworthy or serious cause is ever identified. If the pain resolves after a few weeks, intensive testing is not indicated.[9]

Diagnostic approach

Typically people are treated symptomatically without exact determination of the underlying cause. Only in cases with worrisome signs is diagnostic imaging needed.

Imaging

X-rays, CT or MRI scans are not required in lower back pain except in the cases where "red flags" are present.[10] If the pain is of a long duration X-rays may increase patient satisfaction.[11] However routine imaging may be harmful to a person's health and more imaging is associated with higher rates of surgery but no resultant benefit.[12] From 1994 to 2006, in the United States MRI scans of the lumbar region increased by more than 300%.[13]

Red flags

- Recent significant trauma

- Milder trauma if age is greater than 50 years

- Unexplained weight loss

- Unexplained fever

- Immunosuppression

- Previous or current cancer

- Intravenous drug use

- Osteoporosis

- Chronic corticosteroid use

- Age greater than 70 years

- Focal neurological deficit

- Duration greater than 6 weeks[14]

Risks of unnecessary imaging

Complaints of lower back pain are one of the most common reasons why people visit doctors.[15] Although many patients and doctors try to find the cause of the pain with imaging tests such as an X-ray, CT scan, or MRI, in most cases these tests are not necessary.[15] Most people with lower-back pain feel better after a month regardless of whether they get imaging.[15] Fewer than 1% of imaging tests identify the cause of a problem.[15]

The negative effects of imaging include the following:

- The tests rarely result in a faster or better recovery[15]

- X-rays and CT scans expose the patient to harmful radiation[citation needed]

- They can detect harmless abnormalities which encourage the patient to request further unnecessary testing or to worry[15]

- Testing for acute back pain often leads to unnecessary surgery[15]

- The tests are expensive[15]

Medical societies do not recommend imaging tests for lower back pain within a few weeks of the onset of pain as the pain is likely to subside.[15] The patient can treat the pain with doctor's advice, recommended physical activity, heat, over-the-counter medications, or other options.[citation needed] A doctor may recommend imaging after trying these things and waiting a few weeks first.[15]

Prevention

Exercise is effective in preventing recurrence of non-acute pain, however has shown mixed results in the treatment of acute episodes.[16] Proper lifting techniques may be useful.[17]

Cigarette smoking impacts the success and proper healing of spinal fusion surgery in patients who undergo cervical fusion; rates of nonunion are significantly greater for smokers than for nonsmokers.[18] Smoke and nicotine accelerate spine deterioration, reduce blood flow to the lower spine, and cause discs to degenerate.[19]

Management

Acute pain

- Self care

For acute cases that are not debilitating, low back pain may be best treated with conservative self-care,[20] including: application of heat or cold,[21][22] and continued activity within the limits of the pain.[23][24] Firm mattresses have demonstrated less effectiveness than medium-firm mattresses.[25]

- Activity

Engaging in physical activity within the limits of pain aids recovery. Prolonged bed rest (more than 2 days) is considered counterproductive.[23][26] Even with cases of severe pain, some activity is preferred to prolonged sitting or lying down - excluding movements that would further strain the back.[9] Structured exercise in acute low back pain has demonstrated neither improvement nor harm.[16]

- Physical therapy

Physical therapy can include heat, ice, massage, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation. Active therapies can consist of stretching, strengthening and aerobic exercises. Exercising to restore motion and strength to your lower back can be very helpful in relieving pain and preventing future episodes of low back pain.[27]

- Medications

Short term use of pain and anti-inflammatory medications, such as NSAIDs or acetaminophen may help relieve the symptoms of lower back pain.[26][28] NSAIDs are slightly effective for short-term symptomatic relief in patients with acute and chronic low-back pain without sciatica.[29] Muscle relaxants for acute[26] and chronic[28] pain have some benefit,[30] and are more effective in relieving pain and spasms when used in combination with NSAIDs.[31]

- Spinal manipulation

It is not known if chiropractic care improves clinical outcomes in those with lower back pain more or less than other possible treatments.[32] A 2004 Cochrane review found that spinal manipulation (SM) was no more or less effective than other commonly used therapies such as pain medication, physical therapy, exercises, back school or the care given by a general practitioner[33] which was supported by a 2006 and 2008 review.[34][35] A 2010 systematic review found that most studies suggest SM achieves equal or superior improvement in pain and function when compared with other commonly used interventions for short, intermediate, and long-term follow-up.[36] In 2007 the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society jointly recommended that it be considered for people who do not improve with self care options.[20] A 2007 literature synthesis found good evidence supporting SM and mobilization for low back pain.[37]

Chronic pain

Low back pain is more likely to be persistent among people who previously required time off from work because of low back pain, those who expect passive treatments to help, those who believe that back pain is harmful or disabling or fear that any movement whatever will increase their pain, and people who have depression or anxiety.[9] A systematic review (2010) published as part of the Rational Clinical Examination Series in the Journal of the American Medical Association reviews the factors that predict disability from back pain.[38] The data quantified that patients with back pain who have poor coping behaviors or who fear activity are about 2.5 times as likely to have poor outcomes at 1 year.

The following measures have been found to be effective for chronic non-specific back pain:

- Exercise therapy appears to be slightly effective at reducing pain and improving function in the treatment of chronic low back pain.[39] Compared to usual care, exercise therapy improved post-treatment pain intensity and disability, and long-term function.[40] Exercise programmes are effective for chronic LBP up to 6 months after treatment cessation, evidenced by pain score reduction and reoccurrence rates.[41] There is no evidence that one particular type of exercise therapy is clearly more effective than others.[42] A specialist yoga programme - "Yoga for Healthy Lower Backs" [43] plus usual GP care showed a 30% functional improvement at 3 months (compared to just usual GP care) in a large UK RCT, though yoga was not directly compared against any other exercise regimes. [44] The offer of a course of 12 yoga lessons was highly cost effective, and dominant for society (cheaper and more effective than usual care). It led to 8.5 fewer days off work in a year and had long term benefits. [45]

The Schroth method, a specialized physical exercise therapy for scoliosis, kyphosis, spondylolisthesis, and related spinal disorders, has been shown to reduce severity and frequency of back pain in adults with scoliosis.[46]

- Tricyclic antidepressants are recommended in a 2007 guideline by the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society.[47]

- Acupuncture may help chronic pain;[28] however, a more recent randomized controlled trial suggested insignificant difference between real and sham acupuncture.[48]

- Intensive multidisciplinary treatment programs may help subacute[26] or chronic[28] low back pain.[9]

- Behavioral therapy[28]

- The Alexander Technique was shown in a UK clinical trial to have long-term benefits for patients with chronic back pain.[49]

- Spinal manipulation has been shown to have a clinical effect equal to that of other commonly used therapies and was considered safe.[50]

- Clinical research shows that treatment according to McKenzie method somewhat effective for acute low back pain, but the evidence suggests that it is not effective for chronic low-back pain.[51]

- Manipulation under anaesthesia, or medically-assisted manipulation, currently has insufficient evidence to make any strong recommendations.[52]

- Prolotherapy, facet joint injections, and intradiscal steroid injections have not been found to be effective.[53]

Epidural corticosteroid injections are said to supply the patient with temporary relief of sciatica. However studies show that they do not decrease the rate of ensuing operations.[54] Therapeutic massage is proven to be effective for chronic back pain.[55] Traditional Chinese Medical acupuncture was proven to be relatively ineffective for chronic back pain.[55]

Surgery

Surgery may be indicated when conservative treatment is not effective in reducing pain or when the patient develops progressive and functionally limiting neurologic symptoms such as leg weakness, bladder or bowel incontinence, which can be seen with severe central lumbar disc herniation causing cauda equina syndrome or spinal abscess.[citation needed] Spinal fusion has been shown not to improve outcomes in those with simple chronic low back pain.[56]

The most common types of low back surgery include microdiscectomy, discectomy, laminectomy, foraminotomy, or spinal fusion. Another less invasive surgical technique consists of an implantation of a spinal cord stimulator and typically is used for symptoms of chronic radiculopathy (sciatica). Lumbar artificial disc replacement is a newer surgical technique for treatment of degenerative disc disease, as are a variety of surgical procedures aimed at preserving motion in the spine. According to studies, benefits of spinal surgery are limited when dealing with degenerative discs.[57]

A medical review in March 2009 found the following: Four randomised clinic trials showed that the benefits of spinal surgery are limited when treating degenerative discs with spinal pain (no sciatica). Between 1990 and 2001 there was a 220% increase in spinal surgery, despite the fact that during that period there were no changes, clarifications, or improvements in the indications for surgery or new evidence of improved effectiveness of spinal surgery. The review also found that higher spinal surgery rates are sometimes associated with worse outcomes and that the best surgical outcomes occurred where surgery rates were lower. It also found that use of surgical implants increased the risk of nerve injury, blood loss, overall complications, operating times and repeat surgery while it only slightly improved solid bone fusion rates. There was no added improvement in pain levels or function.[58]

The logic behind spinal fusion is that by fusing two vertebrae together, they will act and function as a solid bone. Since lumbar pain may be caused by excessive motion of the vertebra the goal of spinal fusion surgery is to eliminate that extra motion in between the vertebrae, alleviating pain. If scoliosis or degenerative discs is the problem, the spinal fusion process may be recommended. There are several different ways of performing the spinal fusion procedure; however, none are proven to reduce pain better than the others.[27]

Other

Additional treatments have been more recently reviewed by the Cochrane Collaboration:

- specialist back care Yoga has been found beneficial.[59] [60][61]

- Massage therapy may benefit some patients.[62]

- Heat application may have a modest benefit. The evidence for cold therapy is limited.[63]

- Correcting leg length difference may help by inserting a heel lift or building up the shoe.[64]

- The role of narcotics for chronic low back pain is uncertain.[65]

- A 2008 review found antidepressants ineffective in the treatment of chronic back pain[66] even though some previous studies did find them helpful.[28]

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has not been found to be effective in chronic lower back pain.[67]

Prognosis

Most people with acute lower back pain recover completely over a few weeks regardless of treatments.[68][69] At 6 weeks complete recovery rates have been reported at between 40-90%.[70] For those whose low back pain continues on to chronicity, it is rarely self limiting, as fewer than 10% of those whose low back pain becomes chronic report no pain five years later.[71]

Epidemiology

Over a lifetime 80% of people have lower back pain,[69] with 26% of American adults reporting pain of at least one day in duration every three months.[72] 41% of adults aged between 26 and 44 years reported having back pain in the previous 6 months. In the United States, estimates of the costs of low back pain range between $38 and $50 billion a year and there are 300,000 operations annually. Along with neck operations, back operations are the 3rd most common form of surgery in the United States.[73]

In pregnancy

An estimated 50-70% of pregnant women experience back pain.[74]

As one gets farther along in the pregnancy, due to the additional weight of the fetus, one’s center of gravity will shift forward causing one’s posture to change. This change in posture leads to increasing lower back pain.[74][75]

The increase in hormones during pregnancy is in preparation for birth. This increase of hormones softens the ligaments in the pelvic area and loosens joints. This change in ligaments and joints may alter the support to which one’s back is normally accustomed.[76][77]

References

- ^ "Lower Back Pain Fact Sheet. nih.gov". Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ^ Bogduk M (2003). "Management of chronic low back pain". Medical Journal of Australia. 180 (2): 79–83. PMID 14723591.

- ^ a b irishhealth.com > Lumbago Retrieved on Dec 25, 2009

- ^ Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM; et al. (2009). "Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain". Arthritis Rheum. 60 (10): 3072–80. doi:10.1002/art.24853. PMID 19790051.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Back pain - Causes". NHS. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ Floyd, R., & Thompson, Clem. (2008). Manual of structural kinesiology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages.

- ^ T N Bernard and W H Kirkaldy-Willis, "Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain," Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, no. 217 (April 1987) 266-280.

- ^ Burke,G.L.,MD, (1964). Backache: From Occiput to Coccyx. Vancouver, BC: Macdonald Publishing.

- ^ a b c d Atlas SJ (2010). "Nonpharmacological treatment for low back pain". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 27 (1).

- ^ Chou, R (2009 Feb 7). "Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 373 (9662): 463–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60172-0. PMID 19200918.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "BestBets: Early radiography in acute lower back pain".

- ^ Chou, R (2011 Feb 1). "Diagnostic imaging for low back pain: advice for high-value health care from the American College of Physicians". Annals of internal medicine. 154 (3): 181–9. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00008. PMID 21282698.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, Martin BI (2009). "Overtreating chronic back pain: time to back off?". J Am Board Fam Med. 22: 62–8.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "www.acr.org".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Use of imaging studies for low back pain: percentage of members with a primary diagnosis of low back pain who did not have an imaging study (plain x-ray, MRI, CT scan) within 28 days of the diagnosis" (Document). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2012Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Choi BK, Verbeek JH, Tam WW, Jiang JY (2010). Choi, Brian KL (ed.). "Exercises for prevention of recurrences of low-back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD006555. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006555.pub2. PMID 20091596.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Delavier, Frédéric. Strength training anatomy. Human Kinetics Publishers, 2006. Print.}

- ^ http://www.spineuniverse.com/wellness/cigarette-smoking-its-impact-spinal-fusions

- ^ Mayo Clinic (2008). Back pain guide [on-line].

- ^ a b Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V; et al. (October 2, 2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society". Ann Intern Med. 147 (7): 478–91. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. PMID 17909209.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, Reggars JW, Esterman AJ (2006). French, Simon D (ed.). "Superficial heat or cold for low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD004750. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004750.pub2. PMID 16437495.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Heat or Cold Packs for Neck and Back Strain: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Efficacy. Gregory Garra. 2010; Academic Emergency Medicine - Wiley InterScience".

- ^ a b Hagen KB, Hilde G, Jamtvedt G, Winnem M (2004). Hagen, Kåre Birger (ed.). "Bed rest for acute low-back pain and sciatica". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD001254. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001254.pub2. PMID 15495012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Atlas SJ (2010). "Nonpharmacological treatment for low back pain". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 27 (1): 20–27.

- ^ Kovacs FM, Abraira V, Peña A; et al. (2003). "Effect of firmness of mattress on chronic non-specific low-back pain: randomised, double-blind, controlled, multicentre trial". The Lancet. 362 (9396): 1599–604. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14792-7. PMID 14630439.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Koes B, van Tulder M (2006). "Low back pain (acute)". Clinical evidence (15): 1619–33. PMID 16973062.

- ^ a b http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00311

- ^ a b c d e f van Tulder M, Koes B (2006). "Low back pain (chronic)". Clinical evidence (15): 1634–53. PMID 16973063.

- ^ Roelofs PDDM, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJPM, van Tulder MW (2008). Roelofs, Pepijn DDM (ed.). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD000396. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000396.pub3. PMID 18253976.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "BestBets: Muscle relaxants for acute low back pain".

- ^ Malanga GA, Dunn KR. Low back pain management: approaches to treatment. J Musculoskel Med. 2010;27:305-315.

- ^ Walker, BF (2011 Feb 1). "A Cochrane review of combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain". Spine. 36 (3): 230–42. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318202ac73. PMID 21248591.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Assendelft, Willem JJ; Morton, Sally C; Yu, Emily I; Suttorp, Marika J; Shekelle, Paul G; Assendelft, Willem JJ (2004). Assendelft, Willem JJ (ed.). "Spinal manipulative therapy for low-back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD000447. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000447.pub2. PMID 14973958.

- ^ Bronfort, G; Haas, M; Evans, R; Kawchuk, G; Dagenais, S (2008). "Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with spinal manipulation and mobilization". The Spine Journal. 8 (1): 213–25. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.023. PMID 18164469.

- ^ Murphy, A; Vanteijlingen, E; Gobbi, M (2006). "Inconsistent Grading of Evidence Across Countries: A Review of Low Back Pain Guidelines". Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 29 (7): 576–81, ich prevent, as well as direct, 16/j.jmpt.2006.07.005. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.07.005. PMID 16949948.

- ^ Dagenais, S; Gay, RE; Tricco, AC; Freeman, MD; Mayer, JM (2010). "NASS Contemporary Concepts in Spine Care: spinal manipulation therapy for acute low back pain". The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 10 (10): 918–40. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2010.07.389. PMID 20869008.

- ^ Meeker W, Branson R, Bronfort G; et al. (2007). "Chiropractic management of low back pain and low back related leg complaints" (PDF). Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chou, R; Shekelle, P (2010). "Will this patient develop persistent disabling low back pain?". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (13): 1295–302. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.344. PMID 20371789.

- ^ Hayden, Jill; Van Tulder, Maurits W; Malmivaara, Antti; Koes, Bart W; Hayden, Jill (2005). Hayden, Jill (ed.). "Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD000335. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000335.pub2. PMID 16034851.

- ^ van van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Kuijpers T, Verhagen AP, Ostelo R, Koes BW, van Tulder MW (2011). "A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain". Eur Spine J. 20 (1): 19–39. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1518-3. PMC 3036018. PMID 20640863.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith C, Grimmer-Somers K. (2010). "The treatment effect of exercise programmes for chronic low back pain". J Eval Clin Pract. 16 (3): 484–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01174.x. PMID 20438611.

- ^ van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, Koes BW, van Tulder MW (2010). "Exercise therapy for chronic nonspecific low-back pain". Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 24 (2): 193–204. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.002. PMID 20227641.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Template:Url=http://www.yogaforbacks.co.uk

- ^ Tillbrook H; et al. (2011). "Yoga for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Trial". Annals of Internal Medicine. 1 November (155(9)): 569–578.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Chuang, Ling-Hsiang; et al. (2012). Spine. 15 August 2012 - Volume 37 (18): 1593–1601 http://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Abstract/2012/08150/A_Pragmatic_Multicentered_Randomized_Controlled.10.aspx.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Weiss HR (1993). "Scoliosis-related pain in adults: Treatment influences". Eur J Phys Med Rehabil. 3 (3): 91–94.

- ^ King SA (July 1, 2008). "Update on Treatment of Low Back Pain: Part 2". Psychiatric Times. 25 (8).

- ^ Haake M, Müller HH, Schade-Brittinger C; et al. (2007). "German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for Chronic Low Back Pain: Randomized, Multicenter, Blinded, Parallel-Group Trial With 3 Groups". Arch. Intern. Med. 167 (17): 1892–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.17.1892. PMID 17893311.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paul Little et al.,Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique (AT) lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain, British Medical Journal, August 19, 2008.

- ^ Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Low Back Pain: A Meta-Analysis of Effectiveness Relative to Other Therapies * Willem J.J. Assendelft, * Sally C. Morton, * Emily I. Yu, * Marika J. Suttorp, * and Paul G. Shekelle Ann Intern Med June 3, 2003 138:871-881

- ^ MacHado, LA; De Souza, MS; Ferreira, PH; Ferreira, ML (2006). "The McKenzie method for low back pain: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis approach". Spine. 31 (9): E254–62. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000214884.18502.93. PMID 16641766.

- ^ Dagenais, S; Mayer, J; Wooley, J; Haldeman, S (2008). "Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with medicine-assisted manipulation". The Spine Journal. 8 (1): 142–9. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2007.09.010. PMID 18164462.

- ^ Chou, Roger; Loeser, John D.; Owens, Douglas K.; Rosenquist, Richard W.; Atlas, Steven J.; Baisden, Jamie; Carragee, Eugene J.; Grabois, Martin; Murphy, Donald R. (2009). "Interventional Therapies, Surgery, and Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation for Low Back Pain". Spine. 34 (10): 1066–77. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a1390d. PMID 19363457.

- ^ Armon, C; Argoff, CE; Samuels, J; Backonja, MM; Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology (2007). "Assessment: use of epidural steroid injections to treat radicular lumbosacral pain: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 68 (10): 723–9. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000256734.34238.e7. PMID 17339579.

- ^ a b Cherkin, DC; Eisenberg, D; Sherman, KJ; Barlow, W; Kaptchuk, TJ; Street, J; Deyo, RA (2001). "Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and self-care education for chronic low back pain". Archives of Internal Medicine. 161 (8): 1081–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.8.1081. PMID 11322842.

- ^ "BestBets: Spinal fusion in chronic back pain".

- ^ Mirza, SK; Deyo, RA (2007). "Systematic review of randomized trials comparing lumbar fusion surgery to nonoperative care for treatment of chronic back pain". Spine. 32 (7): 816–23. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000259225.37454.38. PMID 17414918.

- ^ Deyo, RA; Mirza, SK; Turner, JA; Martin, BI (2009). "Overtreating Chronic Back Pain: Time to Back Off?". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 22 (1): 62–8. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.080102. PMC 2729142. PMID 19124635.

- ^ Tillbrook H; et al. (20011). "Yoga for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Trial". Annals of Internal Medicine. 1 November (155(9)): 569–578.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA (2005). "Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial". Ann. Intern. Med. 143 (12): 849–56. PMID 16365466.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams KA, Petronis J, Smith D; et al. (2005). "Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain". Pain. 115 (1–2): 107–17. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.016. PMID 15836974.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Furlan, AD; Brosseau, L; Imamura, M; Irvin, E; Furlan, Andrea (2002). Furlan, Andrea (ed.). "Massage for low-back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD001929. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001929. PMID 12076429.

- ^ French, Simon D; Cameron, Melainie; Walker, Bruce F; Reggars, John W; Esterman, Adrian J; French, Simon D (2006). French, Simon D (ed.). "Superficial heat or cold for low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD004750. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004750.pub2. PMID 16437495.

- ^ Defrin R, Ben Benyamin S, Aldubi RD, Pick CG (2005). "Conservative correction of leg-length discrepancies of 10mm or less for the relief of chronic low back pain". Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 86 (11): 2075–80. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2005.06.012. PMID 16271551.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Deshpande A, Furlan A, Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk D (2007). Deshpande, Amol (ed.). "Opioids for chronic low-back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD004959. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004959.pub3. PMID 17636781.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Urquhart DM, Hoving JL, Assendelft WW, Roland M, van Tulder MW (2008). Urquhart, Donna M (ed.). "Antidepressants for non-specific low back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001703. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001703.pub3. PMID 18253994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dubinsky, R. M.; Miyasaki, J. (2009). "Assessment: Efficacy of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation in the treatment of pain in neurologic disorders (an evidence-based review): Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 74 (2): 173–6. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c918fc. PMID 20042705.

- ^ "BestBets: Prognosis in acute non-traumatic simple lower back pain".

- ^ a b Urquhart, Donna M; Hoving, Jan L; Assendelft, Willem JJ; Roland, Martin; Van Tulder, Maurits W; Urquhart, Donna M (2008). Urquhart, Donna M (ed.). "Antidepressants for non-specific low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD001703. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001703.pub3. PMID 18253994.

- ^ Menezes Costa Lda, C (2012 Aug 7). "The prognosis of acute and persistent low-back pain: a meta-analysis". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 184 (11): E613-24. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111271. PMC 3414626. PMID 22586331.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Missing pipe in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hestbaek, L; Leboeuf-Yde, C; Engberg, M; Lauritzen, T; Bruun, NH; Manniche, C (2003). "The course of low back pain in a general population. Results from a 5-year prospective study". Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 26 (4): 213–9. doi:10.1016/S0161-4754(03)00006-X. PMID 12750654.

- ^ Deyo, Richard A.; Mirza, Sohail K.; Martin, Brook I. (2006). "Back Pain Prevalence and Visit Rates". Spine. 31 (23): 2724–7. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd. PMID 17077742.

- ^ ACSM's resources for clinical exercise physiology: musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, neoplastic, immunologic and hematologic conditions. (2009). Philadelphia, PA: Amer College of Sports.[page needed]

- ^ a b Danforth Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, James. Gibbs, et al, Ch. 1[page needed]

- ^ Williams’s Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 8[page needed]

- ^ http://www.americanpregnancy.org/pregnancyhealth/backpain.html

- ^ http://www.dynamicchiropractic.com/mpacms/dc/article.php?t=7&id=41386