Greaser (subculture)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2009) |

Greasers are a working class youth subculture that originated in the 1950s among young northeastern and southern United States street gangs. The style and subculture then became popular among other types of people, as an expression of rebellion.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, these youths were known as hoods.[1] The name greaser came from their greased-back hairstyle, which involved combing back hair with wax, gel, creams, tonics or pomade. The term greaser reappeared in later decades as part of a revival of 1950s popular culture. One of the first manifestations of this revival was a 1971 American 7 Up television commercial that featured a 1950s greaser saying "Hey remember me? I'm the teen angel." The music act Sha Na Na also played a major role in the revival.

Although the greaser subculture was largely an American youth phenomenon, there were similar subcultures in the United Kingdom, Australia, Italy and Sweden. The 1950s British equivalents were the ton-up boys, who evolved into the rockers in the 1960s. Members of rival subcultures in the UK, such as skinheads, sometimes referred to greasers simply as grease.

Unlike British rockers, American greasers were known more for their love of hot rod cars, not necessarily motorcycles, although both subcultures are known to be fans of classic motorcycles, as well as being fans of 1950s rockabilly music. The equivalent subculture in Australia was the Bodgies and Widgies.

Fashion

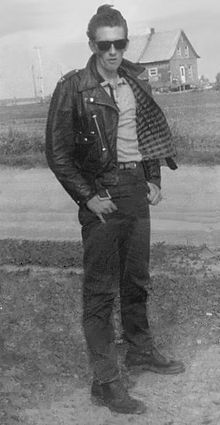

Clothing items usually worn by greasers included: White or black T-shirts (often with the sleeves rolled up); white A-shirts (as outerwear); ringer T-shirts, Italian knit shirts; Daddy-O-style shirts; black, blue or khaki work jackets, black or brown trenchcoats, Levi denim jackets; leather jackets; blue or black Levi's 501 jeans (with rolled-up cuffs anywhere from one to four inches); and baggy cotton twill work trousers company)|Converse]] Chuck Taylor All-Stars. Common accessories included bandannas; stingy-brim hats, flat caps and chain wallets.

Typical hairstyles included the pompadour, the Duck's tail and the more combed-back Folsom style. These hairstyles were held in place with hair wax and sometimes brylcreem (pomade).

Portrayals in popular culture

Greasers are usually portrayed as urban working class ethnics, often Italian American or Hispanic American. The terms greaser or greaseball are ethnic slurs applied to Italian Americans or Hispanic Americans due to stereotypes of either naturally greasier hair or widespread usage of hair grease. Notable exceptions to the urban ethnic portrayal include films such as The Wild One (1953) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and The Outsiders (1983), which portrayed a more rural, southern United States variant of the greaser subculture. Other films and TV shows featuring greasers include: Crime in the Streets (1956), The Delinquents (1957), 77 Sunset Strip (1958), The Young Savages (1961), Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), American Graffiti (1973), Badlands (1973), Happy Days (1974–1984), The Lords of Flatbush (1974), The California Kid (1974), Grease (1978), The Wanderers (1979), Grease 2 (1982), The Loveless (1982), The Outsiders (1983) Eddie and the Cruisers (1983), Rumble Fish (1983), Streets of Fire (1984), Tuff Turf (1985), Stand By Me (1986), La Bamba (1987), Full House (1987–1995), Last Exit to Brooklyn (1989), Cry-Baby (1990), This Boy's Life (1993), Roadracers (1994), Deuces Wild (2002), Secondhand Lions (2003), the children's cartoon Johnny Bravo, the video game Bully (2006), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), Fallout 3 (2008), Mafia II (2010) and Fallout: New Vegas (2010), The Violent Kind (2010)

- '

See also

References

- ^ Marcus, Daniel. Happy Days and Wonder Years: The Fifties and the Sixties in Contemporary Cultural Politics. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2004. p. 12.