Carpool

Carpooling (also known as car-sharing, ride-sharing, lift-sharing and covoiturage), is the sharing of car journeys so that more than one person travels in a car.

By having more people using one vehicle, carpooling reduces each person's travel costs such as fuel costs, tolls, and the stress of driving. Carpooling is also seen as a more environmentally friendly and sustainable way to travel as sharing journeys reduces carbon emissions, traffic congestion on the roads, and the need for parking spaces. Authorities often encourage carpooling, especially during high pollution periods and high fuel prices.

In 2009 carpooling represented 43.5% of all trips in the United States[1] and 10% of commute trips.[2] The majority of carpool commutes (over 60%) are "fam-pools" with family members.[3]

Carpool commuting is more popular for people who work in places with more jobs nearby, and who live in places with higher residential densities.[4] In addition, carpooling is significantly correlated with transport operating costs, including gas prices and commute length, and also with measures of social capital, such as time spent with others, time spent eating and drinking, and being unmarried. However, carpooling is significantly less likely among people who spend more time at work, older workers, and homeowners.[3]

Operation

Drivers and passengers offer and search for journeys through one of the several mediums available. After finding a match they contact each other to arrange any details for the journey(s). Costs, meeting points and other details like space for luggage are agreed on. They then meet and carry out their shared car journey(s) as planned.

Carpooling is commonly implemented for commuting but is increasingly popular for longer one-off journeys, with the formality and regularity of arrangements varying between schemes and journeys.

Carpooling is not always arranged for the whole length of a journey. Especially on long journeys, it is common for passengers to only join for parts of the journey, and give a contribution based on the distance that they travel. This gives carpooling extra flexibility, and enables more people to share journeys and save money.

Today most carpooling is organized thanks to fast-emerging online marketplaces that allow drivers and passengers to find a travel match and make a secured transaction to share the planned travel cost. Like other online marketplaces, they use community-based trust mechanisms, such as user-ratings, to create an optimal experience for users.

Arrangements for carpooling can be made through many different mediums, including:

- Public websites, acting as marketplaces

- Closed websites (e.g. for employees)

- Carpooling smartphone applications

- Manned carpooling agencies

- Pick-up points (not pre-arranged)

Initiatives

Many companies and local authorities have introduced programs to promote carpooling.

In an effort to reduce traffic and encourage carpooling, some governments have introduced high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes in which only vehicles with two or more passengers are allowed to drive. HOV lanes can create strong practical incentives for carpooling by reducing travel time and expense.[5] In some countries it is also common to find parking spaces that are reserved especially for carpoolers.

In 2011, an organization called Greenxc[6] created a campaign to encourage others to use this form of transportation in order to reduce their own carbon footprint.

Carpooling, or car sharing as it is called in British English, is promoted by a national UK charity, Carplus, whose mission is to promote responsible car use in order to alleviate financial, environmental and social costs of motoring today, and encourage new approaches to car dependency in the UK. Carplus is supported by Transport For London, the British government initiative to reduce congestion and parking pressure and contribute to relieving the burden on the environment and to the reduction of traffic related air-pollution, in London.[7]

However not all countries are helping carpooling to spread: in Hungary it is a tax crime to carry someone in a car for a cost share (or any payment) unless the driver has a taxi license and there is an invoice issued and taxes are paid. Several people were fined by undercover tax officers during a 2011 crackdown, posing as passengers looking for a ride on carpooling websites. On 19 March 2012 Endre Spaller, a member of the Hungarian Parliament interpellated Secretary of the State X about this practice who replied that carpooling should be endorsed instead of punished, however care must be taken for some people trying to turn it into a way to gain untaxed profit.[8]

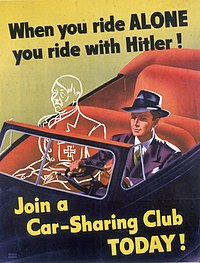

History

Carpooling first became prominent in the United States as a rationing tactic during World War II. It returned in the mid-1970s due to the 1973 oil crisis and the 1979 energy crisis. At that time the first employee vanpools were organized at Chrysler and 3M.[9]

Carpooling declined precipitously between the 1970s and the 2000s, peaking in the US in 1970 with a commute mode share of 20.4%. By 2011 it was down to 9.7%.[10] In large part this has been attributed to the dramatic fall in gas prices (45%) during the 1980s.[11] In addition, the character of carpool travel has been shifting from the "Dagwood Bumstead" variety, in which each rider is picked up in sequence, to a "park and ride" variety, where all the travelers meet at a common location.[3]

Recently, however, the internet has facilitated growth for carpooling and the commute share mode has grown to 10.7% in 2005.[10] The popularity of the internet and mobile phones has greatly helped carpooling to expand, enabling people to offer and find rides thanks to easy-to-use and reliable online transport marketplaces. These websites are commonly used for one-off long-distance journeys with high fuel costs.

Other forms of carpooling

Carpooling also exists in other forms:

- Slugging is a form of ad-hoc, informal carpooling between strangers. No money changes hands, but a mutual benefit still exists between the driver and passenger(s) making the practice worthwhile.

- Flexible carpooling expands the idea of ad-hoc carpooling by designating formal locations for travelers to join carpools.

- Real-time ridesharing allows people to arrange ad-hoc rides on very short notice, through the use of smartphone applications or the internet. Passengers are simply picked up at their current location.

Challenges for carpooling

- Flexibility - Carpooling can struggle to be flexible enough to accommodate en route stops or changes to working times/patterns. One survey identified this as the most common reason for not carpooling.[5] To counter this some schemes offer 'sweeper services' with later running options, or a 'guaranteed ride home' arrangement with a local taxi company.

- Reliability - If a carpooling network lacks a "critical mass" of participants, it may be difficult to find a match for certain trips. In addition, the parties may not necessarily follow through on the agreed-upon ride. Several internet carpooling marketplaces are addressing this concern by implementing online paid passenger reservation, billed even if passengers do not turn up.

- Riding with strangers - Concerns over security have been an obstacle to sharing a vehicle with strangers, though in reality the risk of crime is small.[12] One remedy used by internet carpooling schemes is reputation systems that flag problematic users and allow responsible users to build up trust capital, such systems greatly increase the value of the website for the user community.

- Overall efficacy - Though carpooling is officially sanctioned by most governments, including construction of lanes specifically allocated for car-pooling, some doubts remain as the overall efficacy of car-pooling. As an example, many car-pool lanes, or lanes restricted to car-pools during peak traffic hours, are seldom occupied by car-pools in the traditional sense [citation needed]. Instead, these lanes are often empty, leading to an overall net increase in fuel consumption as freeway capacity is intentionally contracted, forcing the solo-occupied cars to travel slower, leading to reduced fuel efficiency. Further, many of the vehicles are occupied by passengers that would nevertheless consist of multiple passengers, for example a parent with multiple children being escorted to school.

See also

References

- ^ U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, 2009 National Household Travel Survey.

- ^ Park, Haeyoun; Gebeloff/, Robert (28 January 2011). "Car-Pooling Declines as Driving Becomes Cheaper". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Stephen DeLoach and Thomas Tiemann. Not driving alone: Commuting in the Twenty-first century. Elon University Department of Economics. 2010.

- ^ Nathan Belz and Brian Lee. Composition of Vehicle Occupancy for Journey-To-Work Trips: Evidence of Ridesharing from the 2009 National Household Travel Survey Vermont Add-on Sample. Transportation Research Board 2012.

- ^ a b Jianling Li, Patrick Embry, Stephen P. Mattingly, Kaveh Farokhi Sadabadi, Isaradatta Rasmidatta, and Mark W. Burris. Who Chooses to Carpool and Why? Examination of Texas Carpoolers. Transportation Research Record, 2007.

- ^ "GreenXC Website". GreenXC About. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ Source: The state of European Car Sharing, Car Sharing development strategy of greater London, p. 96-98: white-paper by Momo (European research project on sustainable mobility patterns), June 2010

- ^ [1] Demokrata, 19th March 2012

- ^ Marc Oliphant & Andrew Amey. Dynamic Ridesharing: Carpooling Meets the Informaion Age. 2010.

- ^ a b Chan, Nelson D. & Susan A. Shaheen (2012) Ridesharing in North America: Past, Present, and Future. Transport Reviews 32 (1): 93–112.

- ^ Erik Ferguson. The rise and fall of the American carpool: 1970–1990. Transportation 24.4. (1997)

- ^ Hitchhiking: a Viable Addition to a Multimodal Transportation System: Prepared for National Science Foundation, 1975

External links

- Definitions and benefits of carpooling/ridesharing

- Carpooling at the Open Directory Project

- Ridesharing in North America: Past, Present, and Future. Transportation Sustainability Research Center, UC Berkeley