Old King Cole

| "Old King Cole" | |

|---|---|

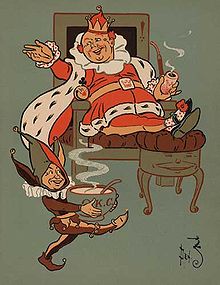

Old King Cole, by William Wallace DenslowBritonnic | |

| Song | |

| Language | English |

| Written | England |

| Published | 1708-9 |

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional |

"Old King Cole" is a British nursery rhyme most likely deriving from ancient Welsh. The historical identity of King Cole has been much debated and several candidates have been advanced as possibilities. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 1164. The poem describes a merry king who called for his pipe, his bowl, and his three fiddlers.

Lyrics

The song was first recorded by William King in his Useful Transactions in Philosophy in 1708–9.[1]

The most common modern version of the rhyme is:

Old King Cole was a merry old soul

And a merry old soul was he;

He called for his pipe, and he called for his bowl

And he called for his fiddlers three.

Every fiddler he had a fiddle,

And a very fine fiddle had he;

Oh there's none so rare, as can compare

With King Cole and his fiddlers three.[1]

William King's version has the following lyrics:

Good King Cole,

And he call'd for his Bowle,

And he call'd for Fidler's three;

And there was Fiddle, Fiddle,

And twice Fiddle, Fiddle,

For 'twas my Lady's Birth-day,

Therefore we keep Holy-day

And come to be merry.[1]

Origins

Cole (or more properly Coel, pronounced like "co-ell" or the English word "coil", and not "coal" as in the rhyme) is a Brythonic name. It may have been borne by a number of noted figures in the history and legends of Roman and sub-Roman Britain, most notably by Coel Hen, or Coel the Old. There are several candidates for a historical basis to the rhyme amongst the historical and mythical Coels.

King Cole of Northern Britain

Coel Hen, whose epithet can be translated as "the Old" or "the Ancestor", is noted in Welsh legend as a leader in the Hen Ogledd or "Old North", the Brythonic-speaking parts of southern Scotland and northern England during or after the period of the Roman withdrawal. The historian John Morris in The Age of Arthur suggested that "The early tradition is that Coel ruled the whole of the north, south of the [Hadrian's] Wall, the territory that the Notitia assigned to the dux [Roman military leader]; but that in later generations it split into a number of independent kingdoms. It suggests that ... he was the last Roman commander, who turned his command into a kingdom."[2] He is credited with founding a number of kingly lines in the North and was regarded as an ancestor figure, suggesting that the territory he controlled must have been substantial.[why?]

Medieval Legend

Later writers such as Henry of Huntington and Geoffrey of Monmouth associate him with Colchester (from where he launched a rebellion which would overthrow the Roman governor Julius Asclepiodotus) and make him the father of Saint Helena of Constantinople, the mother of Constantine the Great.[3][4] Geoffrey's Historia Regum Britanniae expands on the legend of Coel, including material about his rule as king of the Britons and his dealings with the Romans.[4]

Thomas Cole-brook

In the 19th century William Chappell, an expert on popular music, suggested the possibility that the "Old King Cole" of nursery rhyme fame was really "Old Cole", alias Thomas Cole-brook, a supposed 12th-century Reading cloth merchant whose story was recounted by Thomas Deloney in his The Pleasant History of Thomas of Reading (c. 1598), and who was well known as a character in plays of the early 17th century.[1]

Interpretations

"Pipe" may refer to a musical instrument (perhaps a flute or recorder), supported by the final lyrics of the song "there's none so rare, As can compare With King Cole and his fiddlers three", which seem to suggest that King Cole and his fiddlers played music together as a group. The term "pipe" is commonly used as an "informal term for a flute or recorder". The word ceol actually means music in Gaelic, and this may be the origin of the name in the rhyme.[5]

Modern usage

King Cole is often referenced in popular culture.

In popular usage

- In Canada, King Cole is a brand of tea which has been manufactured by G.E. Barbour & Co. since 1910.

In literature

- In his 1897 anthology Mother Goose in Prose, L. Frank Baum included a story explaining the background to the nursery rhyme. In this version, Cole is a commoner who is selected at random to succeed the King of Whatland when the latter dies without heir.

- In James Joyce's Finnegans Wake (619.27f):

With pipe on bowl. Terce for a fiddler, sixt for makmerriers, none for a Cole.

Joyce is at the same time punning on the canonical hours Tierce, Sext, Nones (Terce ... sixt ... none) and on Fionn MacCool (fiddlers ... makmerriers ... Cole).

- Farmer Giles of Ham by J.R.R. Tolkien states that Giles' story is set "after the time of king Cole, but before King Arthur".

In popular music

- Pop singer Nat 'King' Cole (actual surname Coles) said his nickname was inspired by "Old King Cole". The "King" in Nat Cole's name was usually used in quotation marks during his lifetime, but today it is often seen as though it were part of his name.

- The progressive rock band Genesis included the rhyme on their song "The Musical Box", from their 1971 album Nursery Cryme.

- Queen paraphrased the rhyme in their song "Great King Rat" on their 1973 self-titled album:

Great King Rat was a dirty old man

And a dirty old man was he

Now what did I tell you

Would you like to see?

In magazines

- Mad ran a feature postulating classical writers' treatments of fairy tales. The magazine had Edgar Allan Poe tackle "Old King Cole", resulting in a cadence similar to that of "The Bells":

Old King Cole was a merry old soul

Old King Cole, Cole, Cole, Cole, Cole, Cole, Cole.

In humour

- In the 1970s, American comedian George Carlin offered this alternative:

Old King Cole was a merry old soul

And a merry old soul was he;

He called for his pipe, and he called for his bowl -

I guess we all know about Old King Cole...

Carlin's intonation of the final line suggested that the pipe and bowl should be interpreted as marijuana references.

- The United States military also has a version in the form of a marching cadence, used from the 1980s into the present:

Old King Cole was a merry old soul

and a merry ol' soul was he, uh huh.

He called for his pipe, and he called for his bowl

and he called for his privates three, uh huh.

Beer! Beer! Beer! cried the private.

Brave men are we

There's none so fair as they can compare

to the airborne infantry, uh huh.

The cadence included a verse for ranks from private to captain; each verse included a satire at the expense of each rank.

A version can be heard on the 1960 album Belafonte Returns to Carnegie Hall by Harry Belafonte. It can also be found in a 1929 music book "Sound Off!" Soldier songs from Yankee Doodle to Parley Voo" [1] by Edward Arthur Dolph.

In comics and graphic novels

- In the Fables comic book, King Cole was the long-time mayor of 'Fabletown', a secret community of 'Fables', who were forced into exile in our world by a conqueror at home. He was defeated in an election by Prince Charming and was no longer mayor. He then became ambassador of 'Fabletown' to the Arabian fables. After deciding to plan war to win back their homelands, he has since returned to Fabletown, assuming first the post of deputy mayor and then mayor respectively, after the resignation of Prince Charming.

In video games

- In the video game Banjo-Tooie, there is a boss named Old King Coal. After King Coal says that he wishes to battle Banjo and Kazooie, Kazooie reples with "I thought you were a merry old soul?", further referencing the rhyme.

In T.V. shows

- The song was sung on the T.V. show Barney & Friends, but with the last few lyrics changed (which were also adjusted for the drummer and trumpeter verses).

Dance with the fiddlers

Dance with the fiddlers

Dance with the fiddlers three.

The nursery rhyme has also been used in Sesame Street, using the fiddlers as a way to show math, with Ernie taking the role of Old King Cole.

In film

- Walt Disney made a Silly Symphony cartoon in 1933 called "Old King Cole", in which Old King Cole holds a huge party where various nursery rhyme characters are invited.

- Walter Lantz produced an Oswald cartoon in 1933 entitled The Merry Old Soul which is reference to the nursery rhyme.

In political cartoons

- In political cartoons and similar in Britain, sometimes Old King Cole has been used to symbolize the coal industry.

In Yiddish

- In 1927, Moshe Nadir (1885-1943) published his Yiddish version, Der Rebbe Elimelech. It has since become a popular Yiddish folksong.

Notes

- ^ a b c d I. Opie and P. Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford University Press, 1951, 2nd edn., 1997), pp. 134–5.

- ^ Morris, p 54

- ^ Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum Book I, ch. 37.

- ^ a b Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae, Book 5, ch. 6.

- ^ N. Macleod and D. Dewar, A Dictionary of the Gaelic Language, in Two Parts (W. R. M'Phun, 1853), p. 135.

References

- Huntingdon, Henry of (c.1129), Historia Anglorum.

- Kightley, C (1986), Folk Heroes of Britain. Thames & Hudson.

- Monmouth, Geoffrey of (1136). History of the Kings of Britain.

- Morris, John. The Age of Arthur: A History of the British Isles from 350 to 650. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973. ISBN 684-13313-X

- Opie, I & P (1951), The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. Oxford University Press.

- Skene, WF (1868), The Four Ancient Books of Wales. Edmonston & Douglas.