Passenger pigeon

| Passenger Pigeon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Live Passenger Pigeon in 1896, kept by C.O. Whitman | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Ectopistes Swainson, 1827

|

| Species: | E. migratorius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ectopistes migratorius (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| |

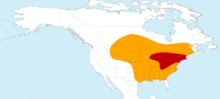

| Distribution map, with breeding zone in red and wintering zone in orange | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Passenger Pigeon or Wild Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) is an extinct North American bird. The species lived in enormous migratory flocks until the early 20th century, when hunting and habitat destruction led to its demise.[2] One flock in 1866 in southern Ontario was described as being 1 mi (1.5 km) wide and 300 mi (500 km) long, took 14 hours to pass, and held in excess of 3.5 billion birds. That number, if accurate, would likely represent a large fraction of the entire population at the time.[3][A][4]

Some estimate 3 to 5 billion Passenger Pigeons were in the United States when Europeans arrived in North America.[B] Others argue the species had not been common in the pre-Columbian period, but their numbers grew when devastation of the American Indian population by European diseases led to reduced competition for food.[C]

The species went from being one of the most abundant birds in the world during the 19th century to extinction early in the 20th century.[1] At the time, Passenger Pigeons had one of the largest groups or flocks of any animal, second only to the Rocky Mountain locust.

Some reduction in numbers occurred from habitat loss when Europeans settlement led to mass deforestation. Next, pigeon meat was commercialized as a cheap food for slaves and the poor in the 19th century, resulting in hunting on a massive and mechanized scale.[citation needed] A slow decline between about 1800 and 1870 was followed by a catastrophic decline between 1870 and 1890.[5] Martha, thought to be the world's last Passenger Pigeon, died on September 1, 1914, at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Taxonomy and systematics

The Passenger Pigeon was a member of the Columbidae family (pigeons and doves) assigned to the genus Ectopistes. Earlier descriptions of the species placed it within the genus Columba, but it was transferred to a monotypic genus due to the greater length of the tail and wings. The fossil record of the bird stretches back to the Pleistocene.[6][7]

The Passenger Pigeon's closest living relative were thought to be the Zenaida doves based on morphological grounds.[8][9][10] The Mourning Dove was even suggested to belong to the genus Ectopistes, as E. carolinensis.[11] However, recent genetic data show it was closer to the American Patagioenas pigeons .[12][13] Rather than belonging (like Zenaida) to the American dove clade around Leptotila, the DNA sequence data show Ectopistes to be part of a radiation that includes the "typical" Old World pigeons (e.g., Domestic Pigeon Columba livia) and the Eurasian turtledoves (Streptopelia) and Patagioenas, as well as the cuckoo-doves and relatives of the Wallacea region and its surroundings.[14] The Passenger Pigeon was able to hybridise with the Eurasian Collared Dove (Streptopelia decaocto) in captivity, but the offspring was infertile.[15]

Etymology

The generic epithet translates as 'wandering about', the specific indicates it is migratory; the Passenger Pigeon's movements were not only seasonal, as with other birds, but also they would mass in whatever location was most productive and suitable for breeding.[16]

In the 18th century, the Passenger Pigeon in Europe was known to the French as tourtre; but, in New France, the North American bird was called tourte. In modern French, the bird is known as the pigeon migrateur.

In Algonquian languages, it was called amimi by the Lenape[17] and omiimii by the Ojibwe.[18] The term "passenger pigeon" in English derives from the French word passager, meaning "to pass by" in a fleeting manner.[19] Jesuit missionary Jacques Gravier's pioneering Kaskaskia-French dictionary explicitly describes and names the passenger pigeon as mimi8a in the Kaskaskia Illinois language, said to be equivalent to tourtre in French.[20]

Description

The Passenger Pigeon was larger than a Mourning Dove and had a body size similar to a large Rock Pigeon. The average weight of these pigeons was 340–400 g (12–14 oz) and, per John James Audubon's account, length was 42 cm (16.5 in) in males and 38 cm (15 in) in females.[21] The Passenger Pigeon had a bluish-gray head and rump, slate-gray back, and a wine-red breast. The male had black streaks on the scapulars and wing coverts and patches of pinkish iridescence at the sides of the neck changed in color to a shining metallic bronze, green, and purple at the back of the neck in various lights. Female and immature birds were similarly marked, but with duller gray on the back, a lighter rose breast and much less iridescent necks.[22] The wings were long and broad.[15] The tail was extremely long at 20–23 cm (8–9 in) and gray to blackish with a white edge.[23]

Behavior and ecology

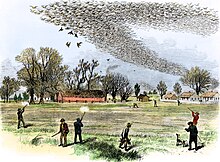

The Passenger Pigeon was a very social bird. It lived in colonies stretching over hundreds of square miles, practicing communal breeding with up to a hundred nests in a single tree. It may have been the most numerous bird on earth in its heyday, and A. W. Schorger believed it accounted for between 25 and 40% of the total landbird population in the US.[24] Pigeon migration, in flocks numbering billions, was a spectacle without parallel,[25] as described by John James Audubon:

I dismounted, seated myself on an eminence, and began to mark with my pencil, making a dot for every flock that passed. In a short time finding the task which I had, undertaken impracticable, as the birds poured in countless multitudes, I rose, and counting the dots then put down, found that 163 had been made in twenty-one minutes. I traveled on, and still met more the farther I proceeded. The air was literally filled with Pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse, the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow; and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose... Before sunset I reached Louisville, distance from Hardensburgh fifty-five miles. The Pigeons were still passing in undiminished numbers, and continued to do so for three days in succession.

Their survival was thought to be based on the benefits of very large numbers.[26] There was safety in large flocks, which often numbered hundreds of thousands of birds. When a flock of this huge size established itself in an area, the number of local animal predators (such as wolves, foxes, weasels, and hawks) was so small compared to the total number of birds, little damage would be inflicted on the flock as a whole. It was common for birds in flocks to perch on each other's backs, an unusual behavior even for socially inclined birds. [citation needed]

The bird is believed to have played a large ecological role in the presettlement forests of North America through tree breakage and depositing of excrement, thereby influencing the distribution of certain tree types.[27]

Diet

The mainstays of the passenger pigeon's diet were beechnuts, acorns, chestnuts, seeds, and berries found in the forests. Worms and insects supplemented the diet in spring and summer. The pigeon was able to disgorge food from its crop when more desirable food became available.[28]

Reproduction

The communal nesting sites were established in forest areas with a sufficient supply of food and water available within daily flying range. A single site might cover many thousands of acres, and the birds were so congested in these areas, hundreds of nests could be counted in a single tree. Since no accurate data were recorded, it is only possible to give estimates on the size and population of these nesting areas. One large nesting area in Wisconsin was reported as covering 850 sq mi (2,200 km2), and the number of birds nesting there was estimated to be around 136,000,000.[29] Breeding took place from March to September, mainly between April and May.[15]

John James Audubon described the courtship of the passenger pigeon as:

The male assumes a pompous demeanor, and follows the female, whether on the ground or on the branches, with spread tail and drooping wings, which it rubs against the part over which it is moving. The body is elevated, the throat swells, the eyes sparkle. He continues his notes, and now and then rises on the wing, and flies a few yards to approach the fugitive and timorous female. Like the domestic Pigeon and other species, they caress each other by billing, in which action, the bill of the one is introduced transversely into that of the other, and both parties alternately disgorge the contents of their crop by repeated efforts.[30]

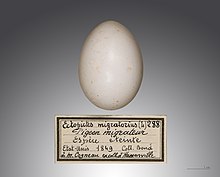

Unlike the behavior described by Audubon, captive specimens did not perform the bowing, strutting, and billing of other pigeons.[15] The nests were loosely constructed of small sticks and twigs, and were about a foot in diameter. A single, white, elongated egg was laid per nesting. The incubation period was from 12 to 14 days. Both parents shared the duties of incubating the egg and feeding the young. The young bird was naked and blind when born, but grew and developed rapidly. When feathered, it was similar in color to the adult female, but its feathers were tipped with white, giving it a scaled appearance. It remained in the nest about 14 days, being fed and cared for by the parent birds. By this time, it had grown large and plump and usually weighed more than either of its parents. It had developed enough to take care of itself and soon fluttered to the ground to hunt for its food.[22]

Habitat and distribution

The time of the spring migration depended on weather conditions. Small flocks sometimes arrived in the northern nesting areas as early as February, but the main migration occurred in March and April. The flocks would travel massive distances, and might not return to a particular location "for decades". Traveling for hours at 60 miles per hour meant vast ranges could be covered.[3] During summer, Passenger Pigeons lived in forest habitats throughout North America east of the Rocky Mountains from eastern and central Canada to the northeastern United States. In the winters, they migrated to the southern United States and occasionally to Mexico and Cuba.[31]

Causes of extinction

The extinction of the Passenger Pigeon had two major causes: commercial exploitation of pigeon meat on a massive scale[22] and loss of habitat.[32]

Large flocks and communal breeding made the species highly vulnerable to hunting.[22] As the flocks dwindled in size, populations decreased below the threshold necessary to propagate the species.[33][34] Naturalist Paul R. Ehrlich wrote that its extinction "illustrates a very important principle of conservation biology: it is not always necessary to kill the last pair of a species to force it to extinction."[2]

Hunting

Prior to colonization, aboriginal Americans occasionally used pigeons for meat. In the early 19th century, commercial hunters began netting and shooting the birds to sell in city markets as food, as live targets for trap shooting, and even as agricultural fertilizer.

Once pigeon meat became popular, commercial hunting started on a prodigious scale. Painter John James Audubon described the preparations for slaughter at a known pigeon-roosting site:

Few pigeons were then to be seen, but a great number of persons, with horses and wagons, guns and ammunition, had already established encampments on the borders. Two farmers from the vicinity of Russelsville, distant more than a hundred miles, had driven upwards of three hundred hogs to be fattened on the pigeons which were to be slaughtered. Here and there, the people employed in plucking and salting what had already been procured, were seen sitting in the midst of large piles of these birds. The dung lay several inches deep, covering the whole extent of the roosting-place.[30]

Pigeons were shipped by the boxcar to the eastern cities. In New York City, in 1805, a pair of pigeons sold for two cents. Slaves and servants in 18th- and 19th-century America often saw no other meat. By the 1850s, the numbers of birds seemed to be decreasing, but still the slaughter continued, accelerating to an even greater level as more railroads were developed after the American Civil War.

Alcohol-soaked grain intoxicated the birds and made them easier to kill. Smoky fires were set to nesting trees to drive them from their nests.[35][36]

At Petoskey, Michigan, in 1878, 50,000 birds were killed each day for nearly five months. The adult birds that survived the slaughter attempted second nestings at new sites, but were killed by professional hunters before they had a chance to raise any young.[22] A state historical marker commemorates the events, including the last great nesting in 1878.[37] Neltje Blanchan, in her book Birds That Hunt and Are Hunted documented that over a million birds were exterminated at one time from a single flock.[35][38] One hunter was reputed to have personally killed "a million birds" and earned $60,000, the equivalent of $1,000,000 today.[39] Paul Ehrlich says a "single hunter" sent three million birds to eastern cities.[2]

Loss of habitat

Another significant reason for its extinction was deforestation.[citation needed] The birds traveled and reproduced in prodigious numbers, satiating predators before any substantial negative impact was made in the bird's habitat. It is unclear the extent to which deforestation impacted important habitats for the species, since large swaths of forested area continued to be present throughout the habitat of the passenger pigeon well into the latter half of the 19th century.

Purported coextinction

An often-cited example of coextinction is that of the Passenger Pigeon and its parasitic lice Columbicola extinctus and Campanulotes defectus. By 2000, however, C. extinctus was rediscovered on the Band-tailed Pigeon, and C. defectus was found to be a likely case of misidentification of the existing Campanulotes flavus.[40][41]

Attempts at preservation

In 1857, a bill was brought forth to the Ohio State Legislature seeking protection for the Passenger Pigeon. A Select Committee of the Senate filed a report stating, "The passenger pigeon needs no protection. Wonderfully prolific, having the vast forests of the North as its breeding grounds, traveling hundreds of miles in search of food, it is here today and elsewhere tomorrow, and no ordinary destruction can lessen them, or be missed from the myriads that are yearly produced."[35][42]

Conservationists were ineffective in stopping the slaughter. A bill was passed in the Michigan legislature making it illegal to net pigeons within two miles (3 km) of a nesting area, but the law was weakly enforced. By the mid-1890s, the Passenger Pigeon almost completely disappeared. In 1897, a bill was introduced in the Michigan legislature asking for a 10-year closed season on Passenger Pigeons. This was a futile gesture. Similar legal measures were passed and disregarded in Pennsylvania.[2] This was a highly gregarious species – the flock could initiate courtship and reproduction only when they were gathered in large numbers; smaller groups of Passenger Pigeons could not breed successfully, and the surviving numbers proved too few to re-establish the species.[22] Attempts at breeding among the captive population also failed for the same reasons. The passenger pigeon was a colonial and gregarious bird practicing communal roosting and communal breeding and needed large numbers for optimum breeding conditions.

By the turn of the 20th century, the last group of passenger pigeons, all descended from the same pair, was kept by Professor Charles O. Whitman at the University of Chicago.[43] The last attempt to breed the remaining specimens was done by Whitman and the Cincinnati Zoo, which included attempts at making a rock dove foster Passenger Pigeon eggs.[44] Whitman sent Martha, which was to be the last known specimen, to Cincinnati Zoo in 1902.[45]

The extinction of the Passenger Pigeon aroused public interest in the conservation movement, and resulted in new laws and practices which prevented many other species from becoming extinct.[22] Naturalist Aldo Leopold paid tribute to the vanished species in an observance held at Wyalusing State Park, Wisconsin, which had been one of the species' social roost sites. Speaking on May 11, 1947, Leopold remarked:

Men still live who, in their youth, remember pigeons. Trees still live who, in their youth, were shaken by a living wind. But a decade hence only the oldest oaks will remember, and at long last only the hills will know.[46]

Some have suggested cloning the Passenger Pigeon in the future.[47][48] Efforts are now underway to revive the species by extracting DNA fragments from preserved specimens, and later, using Band Tailed Pigeons are surrogate parents.[49]

Last wild survivors

The last fully authenticated record of a wild bird was near Sargents, Pike County, Ohio, on March 22, 1900, when the bird was killed by a boy with a BB gun.[22][26][D] Sightings continued to be reported in the 20th century, up until 1930.[50][51][52] All sightings after the Ohio bird, however, are unconfirmed, in spite of rewards offered for a living specimen.[53]

Reports of Passenger Pigeon sightings kept coming in from Arkansas and Louisiana, in groups of tens and twenties, until the first decade of the 20th century.

The naturalist Charles Dury, of Cincinnati, Ohio, wrote in September 1910: "One foggy day in October 1884, at 5 a.m. I looked out of my bedroom window, and as I looked six wild pigeons flew down and perched on the dead branches of a tall poplar tree that stood about one hundred feet away. As I gazed at them in delight, feeling as though old friends had come back, they quickly darted away and disappeared in the fog, the last I ever saw of any of these birds in this vicinity."[54]

Martha

On September 1, 1914, Martha, the last known Passenger Pigeon, died in the Cincinnati Zoo, Cincinnati, Ohio. Her body was frozen into a block of ice and sent to the Smithsonian Institution, where it was skinned, dissected, photographed and mounted.[55] Currently, Martha (named after Martha Washington) is in the museum's archived collection, and not on display.[22][56] A memorial statue of Martha stands on the grounds of the Cincinnati Zoo.[4][57][58][59][60]

John Herald, a bluegrass singer wrote a song dedicated to Martha, titled "Martha: Last of the passenger pigeons". The song tells the story about the Passenger Pigeon's extinction and Martha's life in her cage in Cincinnati Zoo.[61]

See also

Bibliography

Footnotes

- ^ The American Ornithologists' Union meeting in 1909 included a report on how to determine whether the passenger pigeon was extinct, and a reward of $1,200 was offered for proof of even a single nest.Stukel, Eileen Dowd. "Passenger Pigeon". South Dakota Game Fish & Parks. Retrieved March 2, 2012. "Three Hundred Dollars Reward; Will Be Paid for a Nesting Pair of Wild Pigeons, a Bird So Common in the United States Fifty Years Ago That Flocks in the Migratory Period Frequently Partially Obscured the Sun from View. How America Has Lost Birds of Rare Value and How Science Plans to Save Those That Are Left". New York Times. January 16, 1910 Sunday.

Unless the State and Federal Governments come to the rescue of American game, plumed, and song birds, the not distant future will witness the practical extinction of some of the most beautiful and valuable species. Already the snowy heron, that once swarmed in immense droves over the United States, is gone, a victim of the greed and cruelty of milliners whose "creations" its beautiful nuptial feathers have gone to adorn.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) However, the proffered reward was increased on April 4, 1910 to $3,000.00. "Reward for Wild Pigeons. Ornithologists Offer $3,000 for the Discovery of Their Nests". Boston, Massachusetts: The New York Times. April 4, 1910, Monday. Retrieved February 29, 2012.{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) The Cincinnati Zoo upped the offer to $15,000 for finding a mate for Martha. "Passenger Pigeon". si.edu. Smithsonian Institution. March 2001. Retrieved October 28, 2011. - ^ "The Passenger Pigeon". Encyclopedia Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. March, 2001. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) estimated this species once constituted 25 to 40% of the total bird population of the United States. It is estimated that there were 3 billion to 5 billion passenger pigeons at the time Europeans discovered America. - ^ "Prior to 1492, this was a rare species." Mann, Charles C. (2005). "The Artificial Wilderness". 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 315–318. ISBN 1-4000-4006-X.

- ^ The date of March 24 was given in the report by Henniger, but many discrepancies with the actual circumstances meant he was writing from hearsay. A curator's note, apparently derived from an old specimen label, has March 22.

End notes and references

- ^ a b Template:IUCN

- ^ a b c d Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988). "The Passenger Pigeon". Stanford University. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Jerry; Sutton, Bobby (Illustrator); Cronon, William (Foreword) (April 2004). "The Passenger Pigeon: Once There Were Billions". Hunting for Frogs on Elston, and Other Tales from Field & Street. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press: 210–113. ISBN 978-0-226-77993-5. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ a b "Martha, the World's Last Passenger Pigeon". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Magazine. September 1, 2011. Retrieved February 29, 2012. All of these rewards went unclaimed.

- ^ "Passenger Pigeon Timeline" (pdf). Science NetLinks. July 21, 2011. Retrieved February 29, 2012. at Wayback machine

- ^ Howard, Condor 39: 12, 1937

- ^ R. M. Chandler. 1982. A second Pleistocene passenger pigeon from California. Condor 82:242

- ^ "Facts, Save The Doves". Songbird Protection Coalition. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ Miller, Wilmer J. (January 16, 1969). "The Biology and natural history of the Mourning Dove". Should doves be hunted in Iowa?. Ames Iowa Audubon Society, Ringneckdove.com. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ The Mourning Dove in Missouri. Mdc.mo.gov. Retrieved on 2011-12-18.

- ^ American ornithology: or, The natural history of the birds of the United States, Alexander Wilson et al. 1831

- ^ Stauffer, L. Brian (2010-10-06). "Long-Extinct Passenger Pigeon Finds a Place in the Family Tree". Science News, Sciencedaily.com. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.02.017, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.aanat.2011.02.017instead. - ^ Kevin P. Johnson, Dale H. Clayton, John P. Dumbacher, Robert C. Fleischer (2010). "The flight of the Passenger Pigeon: Phylogenetics and biogeographic history of an extinct species". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 57 (1): 455. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.05.010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Hume, J. P.; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. London: A & C Black. pp. 144–146. ISBN 1-4081-5725-X.

- ^ Atkinson, George E. (1907). . In Mershon, W. B (ed.). The Passenger Pigeon. New York: The Outing Publishing Co. p. 188.

- ^ "Extinct Birds the Lenape Knew". Culture and History of the Delaware Tribe. Delaware Tribe www.delawaretribe.org. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ "Omiimii". Ojibwe People's Dictionary. Department of American Indian Studies, University of Minnesota. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ "passenger". On line etymology dictionary. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ Costa, David J.; Wolfart, H.C., ed. (2005). "The St. Jérôme Dictionary of Miami-Illiniois" (pdf). Papers of the 36th Algonquian Conference. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. pp. 107–133. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

{{cite web}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) at 115. - ^ NFC: Passenger Pigeon in my non fish conservation posts :0. Fins.actwin.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History in cooperation with the Public Inquiry Mail Service (March, 2001). "The Passenger Pigeon". Encyclopedia Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Passenger Pigeon". Wild Birds Unlimited, Wbu.com. 1914-09-01. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ The Passenger Pigeon: Its History and Extinction, A. W. Schorger 1955

- ^ "Learn about the Extinct Passenger Pigeon". Project Pigeon Watch. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "Passenger Pigeons: The Extinction of a Species". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00230.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00230.xinstead. - ^ Fuller, Errol (2001). Extinct Birds (revised ed.). Comstock. ISBN 0-8014-3954-X., pp. 96–97

- ^ "The Wisconsin Conservation Hall of Fame: Passenger Pigeons". Wisconsin Conservation Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Audubon, John James. On The Passenger Pigeon. Ulala.org. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Stukel, Eileen Dowd. "Passenger Pigeon". South Dakota Game Fish & Parks. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ "Pigeon Facts – Historical*Comical*Absurd". Australian Avian Research Organization. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Passenger Pigeon, The Extinction Website". The Sixth Extinction. Extinct.petermaas.nl. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/0006-3207(80)90046-4, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/0006-3207(80)90046-4instead. - ^ a b c "Endangered Species Handbook" (pdf). Animal Welfare Institute. 1983. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ "Iowa's Wildlife Resource Base". iowadnr.gov. October 19, 2010. Retrieved February 29, 2012. at Wayback Machine

- ^ "Last Great Gathering of Passenger Pigeons, Crooked Lake Nesting Colony". Petoskey, Michigan: Michigan state historical marker. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ Neltje, Blanchan (1865-1918) (1898). Birds that hunt and are hunted (pdf). New York: Doubleday & McClure Co. p. 359.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Was Martha the last "Pigean de passage"? lifeofbirds.com". Life of birds. January 6, 2007. Retrieved February 29, 2012. at Wayback Machine

- ^ Clayton, D. H., and R. D. Price (1999). "Taxonomy of New World Columbicola (Phthiraptera: Philopteridae) from the Columbiformes (Aves), with descriptions of five new species" (PDF). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 92: 675–685.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Price, R.D., D. H. Clayton, R. J. Adams, J. (2000). "Pigeon lice down under: Taxonomy of Australian Campanulotes (Phthiraptera: Philopteridae), with a description of C. durdeni n.sp. Parasitol" (PDF). American Society of Parasitologists. 86 (5): 948–950.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hornaday, William T. (1913). Our Vanishing Wild Life. Its Extermination and Preservation. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved February 29, 2012. at Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Rothschild, Walter (1907). Extinct Birds (PDF). London: Hutchinson & Co.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.3996/062010-JFWM-017, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.3996/062010-JFWM-017instead. - ^ Patterns of behavior: Konrad Lorenz, Niko Tinbergen, and the founding of ethology, R. W. Burkhardt 2005

- ^ Leopold, Aldo (1949, 1989). A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 0-19-505928-X.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Mecklenborg, Theresa. "Cloning Extinct Species, Part II". Tiger_spot.mapache.org. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ "De-extinction projects now under way". The Long Now Foundation. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- ^ Brand, Stewart. "The dawn of de-extinction. Are you ready?". Stewart Brand: The dawn of de-extinction. Are you ready?. Retrieved 03/23/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Howell, Arthur H. (1924). "Passenger Pigeons in Alabama". Birds of Alabama. p. 384. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Text "publisher-ulala.org." ignored (help) - ^ McKinley, Daniel. A History Of The Passenger Pigeon In Missouri (pdf). Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ "Passenger Pigeon". Science News Letter. 17. Web.ncf.ca.: 136 1930. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ "Reward for Wild Pigeons. Ornithologists Offer $3,000 for the Discovery of Their Nests". Boston, Massachusetts: The New York Times. April 4, 1910, Monday. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dury, Charles (1910). "The Passenger Pigeon". Journal of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History. 21: 52–56.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Shufeld, R. W. (January 1915). "Anatomy of a Passenger Pigeon". The Auk. XXXII (1). Cambridge, Massachusetts: American Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved March 3, 2012. See Archival copies of The Auk.

- ^ ""Martha," The Last Passenger Pigeon". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "Martha - Passenger Pigeon Memorial Hut". Cincinnati, Ohio: Roadside America. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "Passenger Pigeon". si.edu. Smithsonian Institution. March 2001. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ Hahn, P. (1963). Where is that Vanished Bird? An Index to the Known Specimens of the Extinct and Near Extinct North American Species. Royal Ontario Museum.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Enright, Kelly (September 10, 2011). "Memorializing extinction: monuments to the passenger pigeon". Cincinnati Zoo. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Herald, John. "(Martha, last of the) Passenger Pigeons, lyrics and music". Official John Herald website. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

Further reading

- Eckert, Allan W (1965). The Silent Sky: The Incredible Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon. Lincoln NE: IUniverse.com. ISBN 0-595-08963-1. (a novel)

- French, John C. (1919). The Passenger Pigeon in Pennsylvania. Altoona, Pa: Altoona Tribune. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Text "Altoona Tribune Co" ignored (help) at Internet Archive. - Fuller, E. (1987). Extinct Birds. New York, NY: Facts On File Publications. p. 256.

- McGee, M. J. (1910). "Notes on the Passenger Pigeon". Science. 32: 958–964.

- Mershon, W. B., ed. (1907

). . Deposit, New York: Outing Press.

). . Deposit, New York: Outing Press. {{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Price, Jennifer (2000). Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-02486-6.

- Schorger, A.W. (1955). The Passenger Pigeon: Its Natural History and Extinction. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 1-930665-96-2.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - Weidensaul, Scott (1991). The Birder’s Miscellany. New York, NY.: Simon & Schuster. p. 135. ISBN 0-671-69505-3. ISBN 978-0-671-69505-7.

- Weidensaul, Scott (1994). Mountains of the Heart: A Natural History of the Appalachians. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing. ISBN 1-55591-143-9.

External links

- Songbird Foundation: Passenger Pigeon

- The Extinction Website – Passenger Pigeon

- Passenger Pigeon Society

- The Demise of the Passenger Pigeon (as broadcast on NPR's Day to Day)

- 3D view of specimens RMNH 110.048, RMNH 15707, RMNH 110.090, RMNH 110.091, RMNH 110.092, RMNH 110.093, RMNH 110.089, RMNH 110.085, RMNH 110.086, RMNH 110.087 and RMNH 110.088 at Naturalis, Leiden (requires QuickTime browser plugin).

- "Passenger Pigeons". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved March 3, 20123.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

- IUCN Red List extinct species

- Columbidae

- Extinct birds of North America

- Extinct animals of the United States

- Species made extinct by human activities

- Bird extinctions since 1500

- Eastern North American migratory birds

- Natural history of North America

- Genera of birds

- Animals described in 1766

- 1914 in the environment

- Extinct animals of Canada

- Native American cuisine