Ben Jonson

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Ben Jonson | |

|---|---|

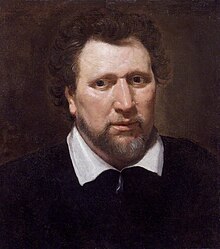

Ben Jonson (c.1617), by Abraham Blyenberch; oil on canvas painting at the National Portrait Gallery, London. | |

| Born | c. 11 June 1572 Westminster, London, England |

| Died | 6 August 1637 (aged 65) Westminster, London, England |

| Occupation | Dramatist, poet and actor |

| Nationality | English |

Ben Jonson (Benjamin Jonson, c. 11 June 1572 – 6 August 1637) was a Jacobean playwright, poet, and literary critic whose artistry much influenced the development of English stage comedy and poetry in the seventeenth century; as dramatist and poet, his renown derives from the satirical plays Every Man in His Humour (1598), Volpone, or The Foxe (1605), The Alchemist (1610), and Bartholomew Fayre: A Comedy (1614); and from lyrical poems such as ″On My First Sonne″ (1616), ″To Celia″ (1616), and ″To Penshurst″ (1616).

As a Classically educated, well-read literary artist, and cultured man of the English Renaissance (1485), possessed of an appetite for controversy (personal and political, artistic and intellectual), Ben Jonson′s intellectual influence was of unparalleled breadth upon the playwrights and the poets of the Jacobean era (1603–1625) and of the Caroline era (1625–1642); as such, he is the second-most important English playwright, after William Shakespeare, whose works were produced during the reign of King James I. [1][2][3]

Early life

Ben Jonson was born an Englishman, in Westminster, London, yet claimed Scottish ancestry, because his family originated from the folk of the Anglo-Scottish border country, which genealogy is verified by the three spindles (rhombi) in the Jonson family coat of arms; the spindle is a diamond-shaped heraldic device shared with the Border-country Johnstone family of Annandale. His clergyman father died two months before Ben's birth; two years later, his mother remarried, to a master bricklayer.[4][5] Jonson attended school in St. Martin's Lane; and later, a family friend paid for his studies at Westminster School, where the antiquarian, historian, topographer, and officer of arms, William Camden (1551–1623) was one of his instructors. In the event, the pupil and the instructor became friends, and the intellectual influence of Camden’s broad-range scholarship upon Jonson’s art and literary style remained notable, until the artist's death in 1623.

On leaving Westminster School, Jonson was to have attended the University of Cambridge, to continue his book learning; but did not, because of his unwilling apprenticeship to his bricklayer stepfather.[4][2] About that time in Jonson’s life, the churchman and historian Thomas Fuller (1608–61) recorded the contemporary Jonsonian legend that the bricklayer Ben Jonson had built a garden wall in Lincoln's Inn. After having been an apprentice bricklayer, Ben Jonson went to the Netherlands, and volunteered to soldier with the English regiments of Francis Vere (1560–1609), in Flanders.

The Hawthornden Manuscripts (1619), of the conversations between Ben Jonson and the poet William Drummond of Hawthornden (1585–1649), reported that, when in Flanders, the soldier Jonson had engaged, fought, and killed an enemy soldier in single combat, and took for trophies the weapons of the vanquished soldier.[6] Upon demobilisation from military service on the Continent, Jonson returned to England and worked as an actor and as a playwright.

As an actor, Jonson was the protagonist “Hieronimo” (Geronimo) in the play The Spanish Tragedy, or Hieronimo is Mad Again (ca. 1586), by Thomas Kyd (1558–94), the first revenge tragedy in English literature. Moreover, by 1597, he was a working playwright employed by Philip Henslowe, the leading producer for the English public theatre; by the next year, the production of Every Man in His Humour (1598) had established Ben Jonson’s reputation as a dramatist.[7][8]

Regarding his personal life, to William Drummond, Jonson described the woman he took to wife as “a shrew, yet honest”. Since the seventeenth century, the identity of Mrs Ben Jonson has been obscure, yet she sometimes is identified as “Ann Lewis”, the woman who married a Benjamin Jonson in 1594, at the church of St Magnus-the-Martyr, near London Bridge.[9]

Concerning the family procreated by Anne Lewis and Ben Jonson, the St. Martin church registers indicate that Mary Jonson, their eldest daughter, died in November 1593, at six months of age. That a decade later, in 1603, Benjamin Jonson, their eldest son, died of Bubonic plague when he was seven years old; to lament and honour the dead boy, Benjamin Jonson père wrote the elegiac On My First Sonne (1603). Moreover, thirty-two years later, a second son, also named Benjamin Jonson, died in 1635. In that period, Mr and Mrs Jonson lived separate lives for five years; their matrimonial arrangement cast Ann Lewis as the housewife Jonson, and Ben Jonson as the artist who enjoyed the residential hospitality of his patrons, Sir Robert Townshend and Lord Aubigny, Esme Stuart, 3rd Duke of Lennox.[9]

Career

In the summer of 1597, at The Rose theatre, the actor Ben Jonson was employed for a fixed engagement with the company of the Admiral's Men, under the management of impresario Philip Henslowe. Based upon uncertain authority, the polymath John Aubrey reported that Jonson was a middling-to-unsuccessful actor. Despite that thespian failing, he proved a successful playwright for The Rose theatre-company, because, by that time, Jonson already had written original plays (tragedies and comedies) for the Admiral’s Men. In the book of literary criticism Palladis Tamia (1598), Francis Meres identified Ben Jonson as a playwright to be considered as one of “the best for tragedy”; because none of the early tragedies survived, the comedy The Case is Altered (1597–98) is the extant stage play from that segment of Ben Jonson’s artistic career.

Late in the year 1597, for offending the cultural and political sensitivities of Britain in the Elizabethan Age (1588–1603), the royal government of Queen Elizabeth I suppressed the performance of the politically offensive play The Isle of Dogs (1597), co-written with Thomas Nashe, for which the Queen’s Interrogator, Richard Topcliffe, ordered the arrest of the authors who wrote, and of the actors who protagonized that seditious satire of the Queen’s councillors. In London, the royal government proffered charges of “Leude and mutynous behavior” against the playwright Ben Jonson (whom they imprisoned at Marshalsea Prison) and against the actors Gabriel Spenser and Robert Shaw; but the co-playwright, Thomas Nashe, escaped arrest because he was out of town, at Great Yarmouth, in coastal Norfolk.

A year later, on 22 September 1598, to resolve a personality conflict, Jonson and Spenser duelled in Hogsden Fields, where playwright killed actor; and Jonson was imprisoned at Newgate Prison.[6] Tried for manslaughter, he pleaded guilty to the crime, but was released by benefit of clergy — his reading of a neck-verse, from the Latin Bible, as if he were a trained cleric — but did suffer the criminal punishments of forfeiting (goods and chattels) and of branding to the left thumb; none the less, that religio–legal ploy earned Jonson lenient punishment for having killed a man in personal quarrel.[10] Whilst in gaol, the idle literary artist occupied himself with the practical uses of abstruse religion, and subsequently converted from the Protestantism of the Church of England to the papist orthodoxy of the Roman Catholic Church, under the influence of a fellow prisoner, the Jesuit priest Fr. Thomas Wright.[11]

Meanwhile, also in 1598, Jonson produced Every Man in His Humour (1598), a comedy that succeeded with the fickle public of the London theatre, by taking advantage of the vogue for comic plays begun with An Humorous Day's Mirth (1597), by George Chapman; the actor William Shakespeare was among the cast of that play. In 1599, Jonson produced the sequel-play Every Man out of His Humour (1599), a stylistically pedantic imitation of Aristophanes. As a learned sequel, heavy with contemporary and historical reference and allusion, Every Man out of His Humour failed on stage, but succeeded in print; to wit, in the year 1600, Ben Jonson required three quarto printings to meet the demand for copies of his very literate play.

At the conclusion of the fifteen-year Elizabethan Age (1588–1603), controversy and quarrel marked the life of Ben Jonson — a conflation of conflicts about Art, politics, and personal temper with his artistic contemporaries; especially notable was the satirical War of the Theatres (1599–1602). In 1600, the company of the The Children of the Chapel Royal, at the Blackfriars Theatre, produced Cynthia's Revels (ca. 1600), a satire of the poet–playwrights John Marston and Thomas Dekker, produced because Jonson believed himself personally maligned by Marston’s accusation of lustfulness, published in the play Histriomastix, or The Player Whipped (1599). A year later, in 1601, with the play Poetaster (1601), Jonson again attacked Marston and Dekker as second-rate poets; Dekker replied with Satiromastix: The Untrussing of a Humorous Poet (1601), a play that concluded with an accurate caricature of Jonson as the acerbic artist portrayed in William Drummond’s personal diary — a braggart literary artist who praised his work and himself, who condemned rival poets as poetasters, and who criticised the shortcomings of production and performance of his plays.

In the event, the four-year War of the Theatres (1599–1602), waged by and among Jonson, Marston, and Dekker, concluded when the querulous artists reconciled their differences of temper and personality, of subject matter and of literary style. Hence, in 1603, Jonson and Dekker co-wrote a welcoming procession for King James I of England; in 1604, Marston dedicated to Jonson the serio-comic revenge tragedy The Malcontent (1603); and, in 1605, Marston and Jonson collaborated with George Chapman as co-authors of Eastward Hoe (1605), a city comedy of anti–Scot sentiment, which earned penitent gaol time for the three playwrights for having offended the Scottish-born King of England — none the less, such scandal assured the play′s commercial success.

Royal patronage

At the beginning of the reign of James I, King of England, in 1603 Jonson joined other poets and playwrights in welcoming the new king. Jonson quickly adapted himself to the additional demand for masques and entertainments introduced with the new reign and fostered by both the king and his consort Anne of Denmark. In addition to his popularity on the public stage and in the royal hall, he enjoyed the patronage of aristocrats such as Elizabeth Sidney (daughter of Sir Philip Sidney) and Lady Mary Wroth. This connection with the Sidney family provided the impetus for one of Jonson's most famous lyrics, the country house poem To Penshurst.

In February 1603 John Manningham reported that Jonson was living on Robert Townsend, son of Sir Roger Townshend, and "scorns the world."[12] Perhaps this explains why his trouble with English authorities continued. That same year he was questioned by the Privy Council about Sejanus, a politically themed play about corruption in the Roman Empire. He was again in trouble for topical allusions in a play, now lost, in which he took part. Shortly after his release from a brief spell of imprisonment imposed to mark the authorities' displeasure at the work, in the second week of October 1605, he was present at a supper party attended by most of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators. After the plot's discovery he appears to have avoided further imprisonment; he volunteered what he knew of the affair to the investigator Robert Cecil and the Privy Council. Father Thomas Wright, who heard Fawkes's confession, was known to Jonson from prison in 1598 and Cecil may have directed him to bring the priest before the council, as a witness.[11] (Teague, 249).

At the same time, Jonson pursued a more prestigious career, writing masques for James's court. The Satyr (1603) and The Masque of Blackness (1605) are two of about two dozen masques which Jonson wrote for James or for Queen Anne; The Masque of Blackness was praised by Algernon Charles Swinburne as the consummate example of this now-extinct genre, which mingled speech, dancing, and spectacle.

On many of these projects he collaborated, not always peacefully, with designer Inigo Jones. For example, Jones designed the scenery for Jonson's masque Oberon, the Faery Prince performed at Whitehall on 1 January 1611 in which Prince Henry, eldest son of James I, appeared in the title role. Perhaps partly as a result of this new career, Jonson gave up writing plays for the public theatres for a decade. He later told Drummond that he had made less than two hundred pounds on all his plays together.

In 1616 Jonson received a yearly pension of 100 marks (about £60), leading some to identify him as England's first Poet Laureate. This sign of royal favour may have encouraged him to publish the first volume of the folio collected edition of his works that year. Other volumes followed in 1640–41 and 1692. (See: Ben Jonson folios)

In 1618 Jonson set out for his ancestral Scotland on foot. He spent over a year there, and the best-remembered hospitality which he enjoyed was that of the Scottish poet, William Drummond of Hawthornden, in April 1619, sited on the River Esk. Drummond undertook to record as much of Jonson's conversation as he could in his diary, and thus recorded aspects of Jonson's personality that would otherwise have been less clearly seen. Jonson delivers his opinions, in Drummond's terse reporting, in an expansive and even magisterial mood. Drummond noted he was "a great lover and praiser of himself, a contemner and scorner of others".

In Edinburgh, Jonson is recorded as staying with a John Stuart of Leith.[4] While there he was made an honorary citizen of Edinburgh. On returning to England, he was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree from Oxford University.

From Edinburgh he travelled west and lodged with the Duke of Lennox where he wrote a play based on Loch Lomond.[4]

The period between 1605 and 1620 may be viewed as Jonson's heyday. By 1616 he had produced all the plays on which his present reputation as a dramatist is based, including the tragedy Catiline (acted and printed 1611), which achieved limited success, and the comedies Volpone, (acted 1605 and printed in 1607), Epicoene, or the Silent Woman (1609), The Alchemist (1610), Bartholomew Fair (1614) and The Devil is an Ass (1616). The Alchemist and Volpone were immediately successful. Of Epicoene, Jonson told Drummond of a satirical verse which reported that the play's subtitle was appropriate, since its audience had refused to applaud the play (i.e., remained silent). Yet Epicoene, along with Bartholomew Fair and (to a lesser extent) The Devil is an Ass have in modern times achieved a certain degree of recognition. While his life during this period was apparently more settled than it had been in the 1590s, his financial security was still not assured.

Religion

Jonson recounted that his father had been a prosperous Protestant landowner until the reign of "Bloody Mary" and had suffered imprisonment and the forfeiture of his wealth during that monarch's attempt to restore England to Catholicism. On Elizabeth's accession he was freed and was able to travel to London to become a clergyman.[13][14] (All we know of Jonson's father, who died a month before his son was born, comes from the poet's own narrative.) Jonson's elementary education was in a small church school attached to St Martin-in-the-Fields parish, and at the age of about seven he secured a place at Westminster School, then part of Westminster Abbey.

Notwithstanding this emphatically Protestant grounding, Jonson maintained an interest in Catholic doctrine throughout his adult life and, at a particularly perilous time while a religious war with Spain was widely expected and persecution of Catholics was intensifying, he converted to the faith.[15][16] This took place in October 1598, while Jonson was on remand in Newgate gaol charged with manslaughter. Jonson's biographer Ian Donaldson is among those who suggest that the conversion was instigated by Father Thomas Wright, a Jesuit priest who had resigned from the order over his acceptance of Queen Elizabeth's right to rule in England.[17][18] Wright, although placed under house arrest on the orders of Lord Burghley, was permitted to minister to the inmates of London prisons.[17] It may have been that Jonson, fearing that his trial would go against him, was seeking the unequivocal absolution that Catholicism could offer if he were sentenced to death.[16] Alternatively, he could have been looking to personal advantage from accepting conversion since Father Wright's protector, the Earl of Essex, was among those who might hope to rise to influence after the succession of a new monarch.[19] Jonson's conversion came at a weighty time in affairs of state; the royal succession, from the childless Elizabeth, had not been settled and Essex's Catholic allies were hopeful that a sympathetic ruler might attain the throne.

Conviction, and certainly not expedience alone, sustained Jonson's faith during the troublesome twelve years he remained a Catholic. His stance received attention beyond the low-level intolerance to which most followers of that faith were exposed. The first draft of his play Sejanus was banned for "popery", and did not re-appear until some offending passages were cut.[11] In January 1606 he (with Anne, his wife) appeared before the Consistory Court in London to answer a charge of recusancy, with Jonson alone additionally accused of allowing his fame as a Catholic to "seduce" citizens to the cause.[20] This was a serious matter (the Gunpowder Plot was still fresh in mind) but he explained that his failure to take communion was only because he had not found sound theological endorsement for the practice, and by paying a fine of thirteen shillings he escaped the more serious penalties at the authorities' disposal. His habit was to slip outside during the sacrament, a common routine at the time—indeed it was one followed by the royal consort, Queen Anne, herself—to show political loyalty while not offending the conscience.[21] Leading church figures, including John Overall, Dean of St Paul's, were tasked with winning Jonson back to orthodoxy, but these overtures were resisted.[22]

In May 1610 King Henri IV of France, a Catholic monarch respected in England for tolerance towards Protestants, was assassinated, purportedly in the name of the Pope, and this seems to have been the immediate cause of Jonson's decision to rejoin the Church of England.[23][24] He did this in flamboyant style, pointedly drinking a full chalice of communion wine at the eucharist to demonstrate his renunciation of the Catholic rite, in which the priest alone drinks the wine.[25][26] The exact date of the ceremony is unknown.[24] However his interest in Catholic belief and practice remained with him until his death.[27]

Decline and death

Jonson began to decline in the 1620s. He was still well-known; from this time dates the prominence of the Sons of Ben or the "Tribe of Ben", those younger poets such as Robert Herrick, Richard Lovelace, and Sir John Suckling who took their bearing in verse from Jonson. However, a series of setbacks drained his strength and damaged his reputation. He resumed writing regular plays in the 1620s, but these are not considered among his best. They are of significant interest, however, for their portrayal of Charles I's England. The Staple of News, for example, offers a remarkable look at the earliest stage of English journalism. The lukewarm reception given that play was, however, nothing compared to the dismal failure of The New Inn; the cold reception given this play prompted Jonson to write a poem condemning his audience (the Ode to Myself), which in turn prompted Thomas Carew, one of the "Tribe of Ben," to respond in a poem that asks Jonson to recognise his own decline.[28]

The principal factor in Jonson's partial eclipse was, however, the death of James and the accession of King Charles I in 1625. Jonson felt neglected by the new court. A decisive quarrel with Jones harmed his career as a writer of court masques, although he continued to entertain the court on an irregular basis. For his part, Charles displayed a certain degree of care for the great poet of his father's day: he increased Jonson's annual pension to £100 and included a tierce of wine.

Despite the strokes that he suffered in the 1620s, Jonson continued to write. At his death in 1637 he seems to have been working on another play, The Sad Shepherd. Though only two acts are extant, this represents a remarkable new direction for Jonson: a move into pastoral drama. During the early 1630s he also conducted a correspondence with James Howell, who warned him about disfavour at court in the wake of his dispute with Jones.

Jonson died on 6 August 1637 and his funeral was held on 9 August. He is buried in the north aisle of the nave in Westminster Abbey, with the inscription "O Rare Ben Johnson" (sic) set in the slab over his grave.[29] John Aubrey, in a more meticulous record than usual, notes that a passer-by, John Young of Great Milton, Oxfordshire, saw the bare grave marker and on impulse paid a workman eighteen pence to make the inscription. Another theory suggests that the tribute came from William D’Avenant, Jonson’s successor as Poet Laureate (and card-playing companion of Young), as the same phrase appears on D'Avenant's nearby gravestone, but essayist Leigh Hunt contends that Davenant's wording represented no more than Young's coinage, cheaply re-used.[29][30] The fact that Jonson was buried in an upright position was an indication of his reduced circumstances at the time of his death,[31] although it has also been written that he asked for a grave exactly 18 inches square from the monarch and received an upright grave to fit in the requested space.[32][33]

It has been claimed that the inscription could be read "Orare Ben Jonson" (pray for Ben Jonson), possibly in an allusion to Jonson's acceptance of Catholic doctrine during his lifetime (although he had returned to the Church of England in about 1610, when anti-Catholic laws once again become more strictly enforced) but the carving shows a distinct space between "O" and "rare".[11][34][35]

His work

Drama

Apart from two tragedies, Sejanus and Catiline, that largely failed to impress Renaissance audiences, Jonson's work for the public theatres was in comedy. These plays vary in some respects. The minor early plays, particularly those written for boy players, present somewhat looser plots and less-developed characters than those written later, for adult companies. Already in the plays which were his salvos in the Poet's War, he displays the keen eye for absurdity and hypocrisy that marks his best-known plays; in these early efforts, however, plot mostly takes second place to variety of incident and comic set-pieces. They are, also, notably ill-tempered. Thomas Davies called Poetaster "a contemptible mixture of the serio-comic, where the names of Augustus Caesar, Maecenas, Virgil, Horace, Ovid, and Tibullus, are all sacrificed upon the altar of private resentment." Another early comedy in a different vein, The Case is Altered, is markedly similar to Shakespeare's romantic comedies in its foreign setting, emphasis on genial wit, and love-plot. Henslowe's diary indicates that Jonson had a hand in numerous other plays, including many in genres such as English history with which he is not otherwise associated.

The comedies of his middle career, from Eastward Ho to The Devil is an Ass are for the most part city comedy, with a London setting, themes of trickery and money, and a distinct moral ambiguity, despite Jonson's professed aim in the Prologue to Volpone to "mix profit with your pleasure". His late plays or "dotages", particularly The Magnetic Lady and The Sad Shepherd, exhibit signs of an accommodation with the romantic tendencies of Elizabethan comedy.

Within this general progression, however, Jonson's comic style remained constant and easily recognisable. He announces his programme in the prologue to the folio version of Every Man in His Humour: he promises to represent "deeds, and language, such as men do use." He planned to write comedies that revived the classical premises of Elizabethan dramatic theory—or rather, since all but the loosest English comedies could claim some descent from Plautus and Terence, he intended to apply those premises with rigour.[36] This commitment entailed negations: after The Case is Altered, Jonson eschewed distant locations, noble characters, romantic plots, and other staples of Elizabethan comedy, focussing instead on the satiric and realistic inheritance of new comedy. He set his plays in contemporary settings, peopled them with recognisable types, and set them to actions that, if not strictly realistic, involved everyday motives such as greed and jealousy. In accordance with the temper of his age, he was often so broad in his characterisation that many of his most famous scenes border on the farcical (as William Congreve, for example, judged Epicoene.) He was more diligent in adhering to the classical unities than many of his peers—although as Margaret Cavendish noted, the unity of action in the major comedies was rather compromised by Jonson's abundance of incident. To this classical model Jonson applied the two features of his style which save his classical imitations from mere pedantry: the vividness with which he depicted the lives of his characters, and the intricacy of his plots. Coleridge, for instance, claimed that The Alchemist had one of the three most perfect plots in literature.

Poetry

Jonson's poetry, like his drama, is informed by his classical learning. Some of his better-known poems are close translations of Greek or Roman models; all display the careful attention to form and style that often came naturally to those trained in classics in the humanist manner. Jonson largely avoided the debates about rhyme and meter that had consumed Elizabethan classicists such as Thomas Campion and Gabriel Harvey. Accepting both rhyme and stress, Jonson used them to mimic the classical qualities of simplicity, restraint, and precision.

“Epigrams” (published in the 1616 folio) is an entry in a genre that was popular among late-Elizabethan and Jacobean audiences, although Jonson was perhaps the only poet of his time to work in its full classical range. The epigrams explore various attitudes, most from the satiric stock of the day: complaints against women, courtiers, and spies abound. The condemnatory poems are short and anonymous; Jonson’s epigrams of praise, including a famous poem to Camden and lines to Lucy Harington, are longer and are mostly addressed to specific individuals. Although it is included among the epigrams, "On My First Sonne" is neither satirical nor very short; the poem, intensely personal and deeply felt, typifies a genre that would come to be called "lyric poetry." It is possible that the spelling of 'son' as 'Sonne' is meant to allude to the sonnet form, with which it shares some features. A few other so-called epigrams share this quality. Jonson's poems of “The Forest” also appeared in the first folio. Most of the fifteen poems are addressed to Jonson’s aristocratic supporters, but the most famous are his country-house poem “To Penshurst” and the poem “To Celia” (“Come, my Celia, let us prove”) that appears also in Volpone.

Underwood, published in the expanded folio of 1640, is a larger and more heterogeneous group of poems. It contains A Celebration of Charis, Jonson’s most extended effort at love poetry; various religious pieces; encomiastic poems including the poem to Shakespeare and a sonnet on Mary Wroth; the Execration against Vulcan and others. The 1640 volume also contains three elegies which have often been ascribed to Donne (one of them appeared in Donne’s posthumous collected poems).

Relationship with Shakespeare

There are many legends about Jonson's rivalry with Shakespeare, some of which may be true. Drummond reports that during their conversation, Jonson scoffed at two apparent absurdities in Shakespeare's plays: a nonsensical line in Julius Caesar, and the setting of The Winter's Tale on the non-existent seacoast of Bohemia. Drummond also reported Jonson as saying that Shakespeare "wanted art" (i.e., lacked skill). Whether Drummond is viewed as accurate or not, the comments fit well with Jonson's well-known theories about literature.

In "De Shakespeare Nostrat" in Timber, which was published posthumously and reflects his lifetime of practical experience, Jonson offers a fuller and more conciliatory comment. He recalls being told by certain actors that Shakespeare never blotted (i.e., crossed out) a line when he wrote. His own response, "Would he had blotted a thousand," was taken as malicious. However, Jonson explains, "He was, indeed, honest, and of an open and free nature, had an excellent phantasy, brave notions, and gentle expressions, wherein he flowed with that facility that sometimes it was necessary he should be stopped".[37] Jonson concludes that "there was ever more in him to be praised than to be pardoned." Also when Shakespeare died, he said, "He was not of an age, but for all time."

Thomas Fuller relates stories of Jonson and Shakespeare engaging in debates in the Mermaid Tavern; Fuller imagines conversations in which Shakespeare would run rings around the more learned but more ponderous Jonson. That the two men knew each other personally is beyond doubt, not only because of the tone of Jonson's references to him but because Shakespeare's company produced a number of Jonson's plays, at least one of which (Every Man in His Humour) Shakespeare certainly acted in. However, it is now impossible to tell how much personal communication they had, and tales of their friendship cannot be substantiated.

Jonson's most influential and revealing commentary on Shakespeare is the second of the two poems that he contributed to the prefatory verse that opens Shakespeare's First Folio. This poem, "To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare and What He Hath Left Us", did a good deal to create the traditional view of Shakespeare as a poet who, despite "small Latine, and lesse Greeke",[38] had a natural genius. The poem has traditionally been thought to exemplify the contrast which Jonson perceived between himself, the disciplined and erudite classicist, scornful of ignorance and sceptical of the masses, and Shakespeare, represented in the poem as a kind of natural wonder whose genius was not subject to any rules except those of the audiences for which he wrote. But the poem itself qualifies this view:

- Yet must I not give Nature all: Thy Art,

- My gentle Shakespeare, must enjoy a part.

Some view this elegy as a conventional exercise, but others see it as a heartfelt tribute to the "Sweet Swan of Avon", the "Soul of the Age!" It has been argued that Jonson helped to edit the First Folio, and he may have been inspired to write this poem by reading his fellow playwright's works, a number of which had been previously either unpublished or available in less satisfactory versions, in a relatively complete form.

Reception and influence

During most of the 17th century Jonson was a towering literary figure, and his influence was enormous for he has been described as 'One of the most vigorous minds that ever added to the strength of English literature'.[39] Before the English Civil War, the "Tribe of Ben" touted his importance, and during the Restoration Jonson's satirical comedies and his theory and practice of "humour characters" (which are often misunderstood; see William Congreve's letters for clarification) was extremely influential, providing the blueprint for many Restoration comedies. In the 18th century Jonson's status began to decline. In the Romantic era, Jonson suffered the fate of being unfairly compared and contrasted to Shakespeare, as the taste for Jonson's type of satirical comedy decreased. Jonson was at times greatly appreciated by the Romantics, but overall he was denigrated for not writing in a Shakespearean vein. In the 20th century, Jonson's status rose significantly.

In 2012, after more than two decades of research, Cambridge University Press published the first new edition for Jonson's complete works for 60 years.[40]

Drama

As G. E. Bentley notes in Shakespeare and Jonson: Their Reputations in the Seventeenth Century Compared, Jonson's reputation was in some respects equal to Shakespeare's in the 17th century. After the English theatres were reopened on the Restoration of Charles II, Jonson's work, along with Shakespeare's and Fletcher's, formed the initial core of the Restoration repertory. It was not until after 1710 that Shakespeare's plays (ordinarily in heavily revised forms) were more frequently performed than those of his Renaissance contemporaries. Many critics since the 18th century have ranked Jonson below only Shakespeare among English Renaissance dramatists. Critical judgment has tended to emphasise the very qualities that Jonson himself lauds in his prefaces, in Timber, and in his scattered prefaces and dedications: the realism and propriety of his language, the bite of his satire, and the care with which he plotted his comedies.

For some critics, the temptation to contrast Jonson (representing art or craft) with Shakespeare (representing nature, or untutored genius) has seemed natural; Jonson himself may be said to initiate this interpretation in the second folio, and Samuel Butler drew the same comparison in his commonplace book later in the century.

At the Restoration, this sensed difference became a kind of critical dogma. Charles de Saint-Évremond placed Jonson's comedies above all else in English drama, and Charles Gildon called Jonson the father of English comedy. John Dryden offered a more common assessment in the Essay of Dramatic Poesie, in which his Avatar Neander compares Shakespeare to Homer and Jonson to Virgil: the former represented profound creativity, the latter polished artifice. But "artifice" was in the 17th century almost synonymous with "art"; Jonson, for instance, used "artificer" as a synonym for "artist" (Discoveries, 33). For Lewis Theobald, too, Jonson “ow[ed] all his Excellence to his Art,” in contrast to Shakespeare, the natural genius. Nicholas Rowe, to whom may be traced the legend that Jonson owed the production of Every Man in his Humour to Shakespeare's intercession, likewise attributed Jonson's excellence to learning, which did not raise him quite to the level of genius. A consensus formed: Jonson was the first English poet to understand classical precepts with any accuracy, and he was the first to apply those precepts successfully to contemporary life. But there were also more negative spins on Jonson's learned art; for instance, in the 1750s, Edward Young casually remarked on the way in which Jonson’s learning worked, like Samson’s strength, to his own detriment. Earlier, Aphra Behn, writing in defence of female playwrights, had pointed to Jonson as a writer whose learning did not make him popular; unsurprisingly, she compares him unfavorably to Shakespeare. Particularly in the tragedies, with their lengthy speeches abstracted from Sallust and Cicero, Augustan critics saw a writer whose learning had swamped his aesthetic judgment.

In this period, Alexander Pope is exceptional in that he noted the tendency to exaggeration in these competing critical portraits: "It is ever the nature of Parties to be in extremes; and nothing is so probable, as that because Ben Johnson had much the most learning, it was said on the one hand that Shakespear had none at all; and because Shakespear had much the most wit and fancy, it was retorted on the other, that Johnson wanted both."[41] For the most part, the 18th century consensus remained committed to the division that Pope doubted; as late as the 1750s, Sarah Fielding could put a brief recapitulation of this analysis in the mouth of a "man of sense" encountered by David Simple.

Though his stature declined during the 18th century, Jonson was still read and commented on throughout the century, generally in the kind of comparative and dismissive terms just described. Heinrich Wilhelm von Gerstenberg translated parts of Peter Whalley's edition into German in 1765. Shortly before the Romantic revolution, Edward Capell offered an almost unqualified rejection of Jonson as a dramatic poet, who (he writes) "has very poor pretensions to the high place he holds among the English Bards, as there is no original manner to distinguish him, and the tedious sameness visible in his plots indicates a defect of Genius."[42] The disastrous failures of productions of Volpone and Epicoene in the early 1770s no doubt bolstered a widespread sense that Jonson had at last grown too antiquated for the contemporary public; if he still attracted enthusiasts such as Earl Camden and William Gifford, he all but disappeared from the stage in the last quarter of the century.

The romantic revolution in criticism brought about an overall decline in the critical estimation of Jonson. Hazlitt refers dismissively to Jonson’s “laborious caution.” Coleridge, while more respectful, describes Jonson as psychologically superficial: “He was a very accurately observing man; but he cared only to observe what was open to, and likely to impress, the senses.” Coleridge placed Jonson second only to Shakespeare; other romantic critics were less approving. The early 19th century was the great age for recovering Renaissance drama. Jonson, whose reputation had survived, appears to have been less interesting to some readers than writers such as Thomas Middleton or John Heywood, who were in some senses “discoveries” of the 19th century. Moreover, the emphasis which the romantic writers placed on imagination, and their concomitant tendency to distrust studied art, lowered Jonson's status, if it also sharpened their awareness of the difference traditionally noted between Jonson and Shakespeare. This trend was by no means universal, however; William Gifford, Jonson's first editor of the 19th century, did a great deal to defend Jonson's reputation during this period of general decline. In the next era, Swinburne, who was more interested in Jonson than most Victorians, wrote, “The flowers of his growing have every quality but one which belongs to the rarest and finest among flowers: they have colour, form, variety, fertility, vigour: the one thing they want is fragrance” – by “fragrance,” Swinburne means spontaneity.

In the 20th century, Jonson’s body of work has been subject to a more varied set of analyses, broadly consistent with the interests and programmes of modern literary criticism. In an essay printed in The Sacred Wood, T. S. Eliot attempted to repudiate the charge that Jonson was an arid classicist by analysing the role of imagination in his dialogue. Eliot was appreciative of Jonson's overall conception and his "surface", a view consonant with the modernist reaction against Romantic criticism, which tended to denigrate playwrights who did not concentrate on representations of psychological depth. Around mid-century, a number of critics and scholars followed Eliot’s lead, producing detailed studies of Jonson’s verbal style. At the same time, study of Elizabethan themes and conventions, such as those by E. E. Stoll and M. C. Bradbrook, provided a more vivid sense of how Jonson’s work was shaped by the expectations of his time.

The proliferation of new critical perspectives after mid-century touched on Jonson inconsistently. Jonas Barish was the leading figure among critics who appreciated Jonson's artistry. On the other hand, Jonson received less attention from the new critics than did some other playwrights and his work was not of programmatic interest to psychoanalytic critics. But Jonson’s career eventually made him a focal point for the revived sociopolitical criticism. Jonson’s works, particularly his masques and pageants, offer significant information regarding the relations of literary production and political power, as do his contacts with and poems for aristocratic patrons; moreover, his career at the centre of London’s emerging literary world has been seen as exemplifying the development of a fully commodified literary culture. In this respect he is seen as a transitional figure, an author whose skills and ambition led him to a leading role both in the declining culture of patronage and in the rising culture of mass consumption.

Poetry

Jonson has been called 'the first poet laureate'.[43] If Jonson's reputation as a playwright has traditionally been linked to Shakespeare, his reputation as a poet has, since the early 20th century, been linked to that of John Donne. In this comparison, Jonson represents the cavalier strain of poetry, emphasising grace and clarity of expression; Donne, by contrast, epitomised the metaphysical school of poetry, with its reliance on strained, baroque metaphors and often vague phrasing. Since the critics who made this comparison (Herbert Grierson for example), were to varying extents rediscovering Donne, this comparison often worked to the detriment of Jonson's reputation.

In his time Jonson was at least as influential as Donne. In 1623, historian Edmund Bolton named him the best and most polished English poet. That this judgment was widely shared is indicated by the admitted influence he had on younger poets. The grounds for describing Jonson as the "father" of cavalier poets are clear: many of the cavalier poets described themselves as his "sons" or his "tribe". For some of this tribe, the connection was as much social as poetic; Herrick described meetings at "the Sun, the Dog, the Triple Tunne". All of them, including those like Herrick whose accomplishments in verse are generally regarded as superior to Jonson's, took inspiration from Jonson's revival of classical forms and themes, his subtle melodies, and his disciplined use of wit. In these respects Jonson may be regarded as among the most important figures in the prehistory of English neoclassicism.

The best of Jonson's lyrics have remained current since his time; periodically, they experience a brief vogue, as after the publication of Peter Whalley's edition of 1756. Jonson's poetry continues to interest scholars for the light which it sheds on English literary history, such as politics, systems of patronage, and intellectual attitudes. For the general reader, Jonson's reputation rests on a few lyrics that, though brief, are surpassed for grace and precision by very few Renaissance poems: "On My First Sonne"; "To Celia"; "To Penshurst"; and the epitaph on boy player Solomon Pavy.

Jonson's works

Plays

- A Tale of a Tub, comedy (c. 1596 revised? performed 1633; printed 1640)

- The Isle of Dogs, comedy (1597, with Thomas Nashe; lost)

- The Case is Altered, comedy (c. 1597–98; printed 1609), with Henry Porter and Anthony Munday?

- Every Man in His Humour, comedy (performed 1598; printed 1601)

- Every Man out of His Humour, comedy ( performed 1599; printed 1600)

- Cynthia's Revels (performed 1600; printed 1601)

- The Poetaster, comedy (performed 1601; printed 1602)

- Sejanus His Fall, tragedy (performed 1603; printed 1605)

- Eastward Ho, comedy (performed and printed 1605), a collaboration with John Marston and George Chapman

- Volpone, comedy (c. 1605–06; printed 1607)

- Epicoene, or the Silent Woman, comedy (performed 1609; printed 1616)

- The Alchemist, comedy (performed 1610; printed 1612)

- Catiline His Conspiracy, tragedy (performed and printed 1611)

- Bartholomew Fair, comedy (performed 31 October 1614; printed 1631)

- The Devil is an Ass, comedy (performed 1616; printed 1631)

- The Staple of News, comedy (performed Feb. 1626; printed 1631)

- The New Inn, or The Light Heart, comedy (licensed 19 January 1629; printed 1631)

- The Magnetic Lady, or Humors Reconciled, comedy (licensed 12 October 1632; printed 1641)

- The Sad Shepherd, pastoral (c. 1637, printed 1641), unfinished

- Mortimer his Fall, history (printed 1641), a fragment

Masques

- The Coronation Triumph, or The King's Entertainment (performed 15 March 1604; printed 1604); with Thomas Dekker

- A Private Entertainment of the King and Queen on May-Day (The Penates) (1 May 1604; printed 1616)

- The Entertainment of the Queen and Prince Henry at Althorp (The Satyr) (25 June 1603; printed 1604)

- The Masque of Blackness (6 January 1605; printed 1608)

- Hymenaei (5 January 1606; printed 1606)

- The Entertainment of the Kings of Great Britain and Denmark (The Hours) (24 July 1606; printed 1616)

- The Masque of Beauty (10 January 1608; printed 1608)

- The Masque of Queens (2 February 1609; printed 1609)

- The Hue and Cry After Cupid, or The Masque at Lord Haddington's Marriage (9 February 1608; printed c. 1608)

- The Entertainment at Britain's Burse (11 April 1609; lost, rediscovered 2004)

- The Speeches at Prince Henry's Barriers, or The Lady of the Lake (6 January 1610; printed 1616)

- Oberon, the Faery Prince (1 January 1611; printed 1616)

- Love Freed from Ignorance and Folly (3 February 1611; printed 1616)

- Love Restored (6 January 1612; printed 1616)

- A Challenge at Tilt, at a Marriage (27 December 1613/1 January 1614; printed 1616)

- The Irish Masque at Court (29 December 1613; printed 1616)

- Mercury Vindicated from the Alchemists (6 January 1615; printed 1616)

- The Golden Age Restored (1 January 1616; printed 1616)

- Christmas, His Masque (Christmas 1616; printed 1641)

- The Vision of Delight (6 January 1617; printed 1641)

- Lovers Made Men, or The Masque of Lethe, or The Masque at Lord Hay's (22 February 1617; printed 1617)

- Pleasure Reconciled to Virtue (6 January 1618; printed 1641) The masque was a failure; Jonson revised it by placing the anti-masque first, turning it into:

- For the Honour of Wales (17 February 1618; printed 1641)

- News from the New World Discovered in the Moon (7 January 1620: printed 1641)

- The Entertainment at Blackfriars, or The Newcastle Entertainment (May 1620?; MS)

- Pan's Anniversary, or The Shepherd's Holy-Day (19 June 1620?; printed 1641)

- The Gypsies Metamorphosed (3 and 5 August 1621; printed 1640)

- The Masque of Augurs (6 January 1622; printed 1622)

- Time Vindicated to Himself and to His Honours (19 January 1623; printed 1623)

- Neptune's Triumph for the Return of Albion (26 January 1624; printed 1624)

- The Masque of Owls at Kenilworth (19 August 1624; printed 1641)

- The Fortunate Isles and Their Union (9 January 1625; printed 1625)

- Love's Triumph Through Callipolis (9 January 1631; printed 1631)

- Chloridia: Rites to Chloris and Her Nymphs (22 February 1631; printed 1631)

- The King's Entertainment at Welbeck in Nottinghamshire (21 May 1633; printed 1641)

- Love's Welcome at Bolsover ( 30 July 1634; printed 1641)

Other works

- Epigrams (1612)

- The Forest (1616), including To Penshurst

- On My First Sonne (1616), elegy

- A Discourse of Love (1618)

- Barclay's Argenis, translated by Jonson (1623)

- The Execration against Vulcan (1640)

- Horace's Art of Poetry, translated by Jonson (1640), with a commendatory verse by Edward Herbert

- Underwood (1640)

- English Grammar (1640)

- Timber, or Discoveries made upon men and matter, as they have flowed out of his daily readings, or had their reflux to his peculiar notion of the times, a commonplace book

- To Celia (Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes), poem

It is in Timber, or Discoveries . . . that Jonson said that the manner in a man used language became a measure of the speaker and of the writer, thus:

Language most shows a man: Speak, that I may see thee. It springs out of the most retired and inmost parts of us, and is the image of the parent of it, the mind. No glass renders a man’s form or likeness so true as his speech. Nay, it is likened to a man; and as we consider feature and composition in a man, so words in language; in the greatness, aptness, sound structure, and harmony of it.

— Ben Jonson, 1640 (posthumous)[44]

As with other English Renaissance dramatists, a portion of Ben Jonson's literary output has not survived. In addition to The Isle of Dogs (1597), the records suggest these lost plays as wholly or partially Jonson's work: Richard Crookback (1602); Hot Anger Soon Cold (1598), with Porter and Henry Chettle; Page of Plymouth (1599), with Dekker; and Robert II, King of Scots (1599), with Chettle and Dekker. Several of Jonson's masques and entertainments also are not extant: The Entertainment at Merchant Taylors (1607); The Entertainment at Salisbury House for James I (1608); and The May Lord (1613–19).

Finally, there are questionable or borderline attributions. Jonson may have had a hand in Rollo, Duke of Normandy, or The Bloody Brother, a play in the canon of John Fletcher and his collaborators. The comedy The Widow was printed in 1652 as the work of Thomas Middleton, Fletcher and Jonson, though scholars have been intensely sceptical about Jonson's presence in the play. A few attributions of anonymous plays, such as The London Prodigal, have been ventured by individual researchers, but have met with cool responses.[45]

Biographies of Ben Jonson

- Ben Jonson: His Life and Work by Rosalind Miles

- Ben Jonson: His Craft and Art by Rosalind Miles

- Ben Jonson: A Literary Life by W. David Kay

- Ben Jonson: A Life by David Riggs (1989)

- Ben Jonson: A Life by Ian Donaldson (2011)

Notes

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/306058/Ben-Jonson

- ^ a b “Ben Jonson”, Grolier Encyclopedia of Knowledge, volume 10, p. 388.

- ^ Evans, Robert C (2000). "Jonson's critical heritage". In Harp, Richard; Stewart, Stanley (ed.). The Cambridge companion to Ben Jonson. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–202. ISBN 0-521-64678-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c d Robert Chambers, Book of Days

- ^ “Ben Jonson”, Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Edition, pp. 611

- ^ a b Drummond, William (1619). Heads of a Conversation betwixt the Famous Poet Ben Johnson and William Drummond of Hawthornden, January 1619.

- ^ “Ben Jonson”, Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Edition, p. 611

- ^ “Thomas Kyd”, Grolier Encyclopedia of Knowledge, volume 11, p. 122.

- ^ a b “Ben Jonson”, Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Edition, p. 612.

- ^ 1911 Encyclopedia biography

- ^ a b c d Donaldson, Ian (2008). "Benjamin Jonson (1572–1637)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15116.

- ^ Donaldson 2011, p. 181.

- ^ Donaldson (2011: 56)

- ^ Riggs (1989: 9)

- ^ Donaldson (2011: 176)

- ^ a b Riggs (1989: 51–52)

- ^ a b Donaldson (2011: 134–140)

- ^ Harp; Stewart (2000: xiv)

- ^ Donaldson (2011: 143)

- ^ Donaldson (2011: 229)

- ^ Maxwell, Julie (2010). "Religion". In Sanders, Julie (ed.). Ben Jonson in context. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-521-89571-2.

- ^ Donaldson (2011: 228–9)

- ^ Walker, Anita (1995). "Mind of an Assassin: Ravaillac and the Murder of Henri IV of France". Canadian Journal of History. 30. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: 201–229.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Donaldson (2011: 272)

- ^ Jon Morrill, quoted in Donaldson (2011: 487)

- ^ Riggs (1989: 177)

- ^ van den Berg, Sara. "True relation: the life and career of Ben Jonson". In Harp, Richard; Stewart, Stanley (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ben Jonson. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-521-64678-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Maclean, p. 88

- ^ a b "Monuments & Gravestones: Ben Jonson". Westminster Abbey 1065 to today. Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 7 January 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- ^ Hunt, Leigh (9 April 1828). "His epitaph, and Ben Jonson's". Life of Sir William Davenant, with specimens of his poetry. The Companion. Vol. XIV. p. 187. OCLC 2853686.

- ^ Adams, J. Q. The Jonson Allusion Book. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1922. pp. 195–6

- ^ Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and Its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 34.

- ^ Donaldson (2011:1)

- ^ Stubbs, John (24 February 2011). Reprobates. London: Viking Penguin. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-670-91753-2.

…a plea for the passerby's prayers (the Latin imperative orare)…

- ^ Fletcher, Angus (2007). "Structure of an epitaph". Time, space, and motion in the age of Shakespeare. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-674-02308-6.

At first sight the words seem clear enough…but some…have believed that the words intended to say, in Latin, "Pray for Ben Jonson"…

- ^ Doran, 120ff

- ^ Gutenberg.org

- ^ W.T. Baldwin 's William Shakspere's Smalle Latine and Lesse Greeke, 1944

- ^ Morley, Henry, Introduction to Discoveries Made Upon Men and Matter and Some Poems 1892 kindle ebook 2011 ASIN B004TOT8FQ

- ^ "Why should William Shakespeare have the last word over Ben Jonson?" at telegraph.co.uk/

- ^ Alexander Pope, ed. Works of Shakespeare (London, 1725), p. 1

- ^ Quoted in Craig, D. H., ed. Jonson: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge, 1995). p. 499

- ^ Schmidt, Michael, Lives of the Poets, Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1998 ISBN 9780753807453

- ^ Jonson, B., "Discoveries and Some Poems," Cassell & Company, 1892.

- ^ Logan and Smith, pp. 82–92

References

- Bednarz, James P. Shakespeare and the Poets' War. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

- Bentley, G. E. Shakespeare and Jonson: Their Reputations in the Seventeenth Century Compared. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1945

- Bush, Douglas. English Literature in the Earlier Seventeenth Century, 1600–1660. Oxford History of English Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1945

- Butler, Martin. "Jonson's Folio and the Politics of Patronage." Criticism 35 (1993)

- Chute, Marchette. Ben Jonson of Westminster. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1953

- Doran, Madeline. Endeavors of Art. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1954

- Donaldson, Ian (2011). Ben Jonson: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 181–2. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eccles, Mark. "Jonson's Marriage." Review of English Studies 12 (1936)

- Eliot, T.S. "Ben Jonson." The Sacred Wood. London: Methuen, 1920

- Jonson, Ben. Discoveries 1641, ed. G. B. Harrison. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966

- Knights, L. C. Drama and Society in the Age of Jonson. London: Chatto and Windus, 1968

- Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith. The New Intellectuals: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama. Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 1975

- MacLean, Hugh, editor. Ben Jonson and the Cavalier Poets. New York: Norton Press, 1974

- Ceri Sullivan, The Rhetoric of Credit. Merchants in Early Modern Writing (Madison/London: Associated University Press, 2002)

- Teague, Frances. "Ben Jonson and the Gunpowder Plot." Ben Jonson Journal 5 (1998). pp. 249–52

- Thorndike, Ashley. "Ben Jonson." The Cambridge History of English and American Literature. New York: Putnam, 1907–1921

External links

- Digitized Facsimiles of Jonson's second folio, 1640/1 Jonson's second folio, 1640/1

- Video interview with scholar David Bevington The Collected Works of Ben Jonson

- Audio resources on Ben Jonson at TheEnglishCollection.com

- Poems by Ben Jonson at PoetryFoundation.org

- Works by Ben Jonson at Project Gutenberg

- Works of Ben Jonson

- Ben Jonson at Find-A-Grave

- Audio: Robert Pinsky reads "His Excuse For Loving" by Ben Jonson

- Audio: Robert Pinsky reads "My Picture Left in Scotland" by Ben Jonson

- Free scores by Ben Jonson in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- "Archival material relating to Ben Jonson". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Benjamin Jonson at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Use dmy dates from August 2011

- English dramatists and playwrights

- English people convicted of manslaughter

- English poets

- British Poets Laureate

- English prisoners and detainees

- English Renaissance dramatists

- People from Westminster

- People educated at Westminster School, London

- People of the Tudor period

- Duellists

- Anglo-Scots

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- 1572 births

- 1637 deaths

- Grammarians of English

- 16th-century English people

- 17th-century English people

- 16th-century English writers

- 17th-century English writers

- 16th-century poets

- 17th-century poets

- People of the Stuart period

- 16th-century dramatists and playwrights

- 17th-century dramatists and playwrights

- English people of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604)