White blood cell

| White blood cell | |

|---|---|

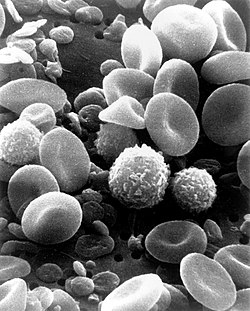

A scanning electron microscope image of normal circulating human blood. In addition to the irregularly shaped leukocytes, both red blood cells and many small disc-shaped platelets are visible. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | leucocytus |

| MeSH | D007962 |

| TH | H2.00.04.1.02001 |

| FMA | 62852 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

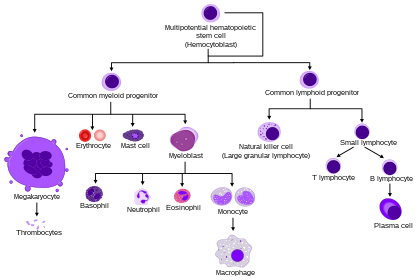

White blood cells, or leukocytes (also spelled "leucocytes") are cells of the immune system involved in defending the body against both infectious disease and foreign materials. Five[1] different and diverse types of leukocytes exist, but they are all produced and derived from a multipotent cell in the bone marrow known as a hematopoietic stem cell. They live for about three to four days in the average human body. Leukocytes are found throughout the body, including the blood and lymphatic system.[2]

The number of leukocytes in the blood is often an indicator of disease. There are normally approximately 70,000 white blood cells per microliter of blood. They make up approximately 1% of the total blood volume in a healthy adult.[3] An increase in the number of leukocytes over the upper limits is called leukocytosis, and a decrease below the lower limit is called leukopenia. The physical properties of leukocytes, such as volume, conductivity, and granularity, may change due to activation, the presence of immature cells, or the presence of malignant leukocytes in leukemia, and may be reported as Cell Population Data.

Etymology

The name "white blood cell" derives from the fact that after centrifugation of a blood sample, the white cells are found in the buffy coat, a thin, typically white layer of nucleated cells between the sedimented red blood cells and the blood plasma. The scientific term leukocyte (from the Greek word leuko- meaning "white" and kytos meaning "hollow vessel", with -cyte translated as "cell" in modern usage) directly reflects this description. Buffy coat may sometimes be green if there are large amounts of neutrophils in the sample, due to the heme-containing enzyme myeloperoxidase that they produce.

Types

There are several different types of white blood cells. They all have many things in common, but are all distinct in form and function. A major distinguishing feature of some leukocytes is the presence of granules; white blood cells are often characterized as granulocytes or agranulocytes:

- Granulocytes (polymorphonuclear leukocytes): leukocytes characterized by the presence of differently staining granules in their cytoplasm when viewed under light microscopy. These granules (usually lysozymes) are membrane-bound enzymes that act primarily in the digestion of endocytosed particles. There are three types of granulocytes: neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils, which are named according to their staining properties.

- Agranulocytes (mononuclear leukocytes): leukocytes characterized by the apparent absence of granules in their cytoplasm. Although the name implies a lack of granules these cells do contain non-specific azurophilic granules, which are lysosomes.[4] The cells include lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages.[5]

Overview table

This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, overview table lists 7 types, but other areas indicate 5 types. Also, macrophages and dendritic cells are derived/differentiated from monocytes, so there really are 5 main types. (September 2011) |

| Type | Microscopic Appearance | Diagram | Approx. % in adults See also: Blood values |

Diameter (μm)[6] | Main targets[3] | Nucleus[3] | Granules[3] | Lifetime[6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil |  |

|

62% | 10–12 | multilobed | fine, faintly pink (H&E stain) | 6 hours–few days (days in spleen and other tissue) | |

| Eosinophil |  |

|

2.3% | 10–12 |

|

bi-lobed | full of pink-orange (H&E stain) | 8–12 days (circulate for 4–5 hours) |

| Basophil |  |

0.4% | 12–15 |

|

bi-lobed or tri-lobed | large blue | a few hours to a few days | |

| Lymphocyte |  |

30% | Small lymphocytes 7–8 Large lymphocytes 12–15 |

|

deeply staining, eccentric | NK-cells and cytotoxic (CD8+) T-cells | years for memory cells, weeks for all else. | |

| Monocyte |  |

5.3% | 12–20[7] | Monocytes migrate from the bloodstream to other tissues and differentiate into tissue resident macrophages, Kupffer cells in the liver. | kidney shaped | none | hours to days | |

| Macrophage |  |

|

approx 21 and sometimes as great as 60–80 | Is a monocyte derivative. Phagocytosis (engulfment and digestion) of cellular debris and pathogens, and stimulation of lymphocytes and other immune cells that respond to the pathogen. | activated: days immune: months to years | |||

| Dendritic cells | Can be myeloid or lymphoid derived. Main function is as an antigen-presenting cell (APC) that activates T lymphocytes. | similar to macrophages |

Neutrophil

Neutrophils defend against bacterial or fungal infection. They are usually first responders to microbial infection; their activity and death in large numbers forms pus. They are commonly referred to as polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes, although, in the technical sense, PMN refers to all granulocytes. They have a multi-lobed nucleus that may appear like multiple nuclei, hence the name polymorphonuclear leukocyte. The cytoplasm may look transparent because of fine granules that are pale lilac. Neutrophils are very active in phagocytosing bacteria and are present in large amount in the pus of wounds. These cells are not able to renew their lysosomes (used in digesting microbes) and die after having phagocytosed a few pathogens.[8] Neutrophils are the most common cell type seen in the early stages of acute inflammation, and make up 60-70% of total leukocyte count in human blood.[3] The life span of a circulating human neutrophil is about 5.4 days.[9]

Eosinophil

Eosinophils primarily deal with parasitic infections. Eosinophils are also the predominant inflammatory cells in allergic reactions. The most important causes of eosinophilia include allergies such as asthma, hay fever, and hives; and also parasitic infections. In general, their nucleus is bi-lobed. The cytoplasm is full of granules that assume a characteristic pink-orange color with eosin stain.

Basophil

Basophils are chiefly responsible for allergic and antigen response by releasing the chemical histamine causing vasodilation. The nucleus is bi- or tri-lobed, but it is hard to see because of the number of coarse granules that hide it. They are characterized by their large blue granules.

Lymphocyte

Lymphocytes are much more common in the lymphatic system. Lymphocytes are distinguished by having a deeply staining nucleus that may be eccentric in location, and a relatively small amount of cytoplasm. The blood has three types of lymphocytes:

- B cells make antibodies that bind to pathogens to enable their destruction.

- T cells:

- CD4+ helper T cells: T cells having co-receptor CD4 are known as CD4+ T cells. These cells bind antigen presented by antigen-presenting cells via T-cell receptor interacting with MHC II complex on APC. Helper T cells coordinate the immune response. In acute HIV infection, these T cells are the main index to identify the individual's immune system activity.

- CD8+ cytotoxic T cells: T cells having co-receptor CD8 are known as CD8+ T cells. These cells bind antigens presented on MHC I complex of virus-infected or tumour cells and kill them. All nucleated cells possess MHC I on their surfaces.

- γδ T cells possess an alternative T cell receptor as opposed to CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells and share characteristics of helper T cells, cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells.

- Natural killer cells are able to kill cells of the body that have lost MHC I molecule, as they have been infected by a virus or have become cancerous.

Monocyte

Monocytes share the "vacuum cleaner" (phagocytosis) function of neutrophils, but are much longer lived as they have an additional role: they present pieces of pathogens to T cells so that the pathogens may be recognized again and killed, or so that an antibody response may be mounted. Monocytes eventually leave the bloodstream to become tissue macrophages, which remove dead cell debris as well as attacking microorganisms. Neither of these can be dealt with effectively by the neutrophils. Unlike neutrophils, monocytes are able to replace their lysosomal contents and are thought to have a much longer active life. They have the kidney shaped nucleus and are typically agranulated. They also possess abundant cytoplasm.

Once monocytes move from the bloodstream out into the body tissues, they undergo changes (differentiate) allowing phagocytosis and are then known as macrophages.

Medication causing leukopenia

Some medications can have an impact on the number and function of white blood cells. Leukopenia is the reduction in the number of white blood cells, which may affect the overall white cell count or one of the specific populations of white blood cells. For example, if the number of neutrophils is low, the condition is known as neutropenia. Likewise, low lymphocyte levels are termed lymphopenia. Medications that can cause leukopenia include clozapine, an antipsychotic medication with a rare adverse effect leading to the total absence of all granulocytes (neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils). Other medications include immunosuppressive drugs, such as sirolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine. Interferons used to treat multiple sclerosis, like Rebif, Avonex, and Betaseron, can also cause leukopenia.

Fixed leukocytes

Some leukocytes migrate into the tissues of the body to take up a permanent residence at that location rather than remaining in the blood. Often these cells have specific names depending upon which tissue they settle in, such as fixed macrophages in the liver, which become known as Kupffer cells. These cells still serve a role in the immune system.

- Histiocytes

- Dendritic cells (Although these will often migrate to local lymph nodes upon ingesting antigens)

- Mast cells

- Microglia

See also

References

- ^ LaFleur-Brooks, M. (2008). Exploring Medical Language: A Student-Directed Approach, 7th Edition. St. Louis, Missouri, USA: Mosby Elsevier. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-323-04950-4.

- ^ Maton, D., Hopkins, J., McLaughlin, Ch. W., Johnson, S., Warner, M. Q., LaHart, D., & Wright, J. D., Deep V. Kulkarni (1997). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Alberts, B. (2005). "Leukocyte functions and percentage breakdown". Molecular Biology of the Cell. NCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ Gartner, L. P., & Hiatt, J. L. (2007). Color Textbook of Histology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: SAUNDERS Elsevier. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-4160-2945-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.wisc-online.com/objects/index_tj.asp?objID=AP14704

- ^ a b Daniels, V. G., Wheater, P. R., & Burkitt, H. G. (1979). Functional histology: A text and colour atlas. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-01657-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Handin, Robert I. (2003). Blood: Principles and Practice of Hematology (Second ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. p. 471. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wheater, Paul R.; Stevens, Alan (2002). Wheater's basic histopathology: a colour atlas and text (PDF). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-07001-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pillay J, den Braber I, Vrisekoop N, Kwast LM, de Boer RJ, Borghans JA, Tesselaar K, Koenderman L. In vivo labeling with 2H2O reveals a human neutrophil lifespan of 5.4 days Blood. 2010 Jul 29;116(4):625-7.

External links

- Atlas of Hematology

- Leukocytes at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)