Hans Morgenthau

Hans Morgenthau | |

|---|---|

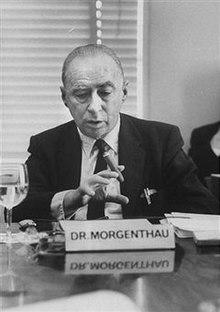

Morgenthau in 1963 | |

| Born | Hans Joachim Morgenthau February 17, 1904 |

| Died | July 19, 1980 (aged 76) |

| Nationality | German-American |

Hans Joachim Morgenthau (February 17, 1904 – July 19, 1980) was one of the leading twentieth-century figures in the study of international politics. He made landmark contributions to international relations theory and the study of international law, and his Politics Among Nations, first published in 1948, went through five editions during his lifetime.

Morgenthau also wrote widely about international politics and U.S. foreign policy for general-circulation publications such as The New Leader, Commentary, Worldview, The New York Review of Books, and The New Republic. He knew and corresponded with many of the leading intellectuals and writers of his era, such as Reinhold Niebuhr,[1] George F. Kennan,[2] and Hannah Arendt.[3] At one point in the early Cold War, Morgenthau was a consultant to the U.S. Department of State when Kennan headed its Policy Planning Staff, and a second time during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations until he was dismissed when he began to publicly express his position of dissent concerning American involvement in Vietnam.[4] For most of his career, however, Morgenthau was esteemed as an academic interpreter of U.S. foreign policy.[5]

Life

Morgenthau was born in an Ashkenazi Jewish family in Coburg, Germany in 1904, and, after attending Casimirianum, was educated at the universities of Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich, and pursued postgraduate work at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. While still a student, Morgenthau was influenced by one of his professors, Prof. Sitzheimer, who was a dedicated Weberian scholar in allowing Morgenthau[6] to adopt one of his preferred methodological preferences.[7][8] He taught and practiced law in Frankfurt before emigrating to the United States in 1937, after several interim years in Switzerland and Spain. Morgenthau taught for many years at the University of Chicago until 1973.

Throughout his life, Morgenthau maintained a reputation as being a highly dedicated and loyal supporter of colleagues and friends. When his then student, Tang Tsou (d. 12 August 1999),[9] at the University of Chicago was challenged by the Department of Immigration concerning his papers, Morgenthau rushed to his assistance, and Tsou would eventually become a respected member of the faculty at the University of Chicago himself. When his son became involved in dissent against the U.S. Army, Morgenthau was central in retaining adequate legal counsel to support his son.[10] In 1975, when his close colleague Hannah Arendt died, Morgenthau wrote a moving memorial notice[11] for her in the press which would recognize her importance to him.[12]

In 1973 he moved to New York and separated from his wife who remained in Chicago partly due to medical issues. He is reported twice to have tried to initiate plans to start a new family while in New York, once with the political philosopher Hannah Arendt as documented by her biographer,[13] and, a second time with Ethel Person (d. 2012), a medical professor at Columbia University when she was between marriages as she documents this in her essay for the Morgenthau Centenary in 2004.[14] Following 1973 and until the end of his career he taught at the New School for Social Research and the City University of New York.

On October 8, 1979, Morgenthau was one of the passengers on board Swissair Flight 316, which crashed while trying to land at Athens-Ellinikon International Airport,[15] while he was en route on a flight destined for Bombay and Peking.

Morgenthau died after a brief hospitalization on July 19, 1980, after being admitted with a grave diagnosis of a perforated ulcer at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York according to the account recorded by Ethel Person.[16] He was survived by his two children, Matthew and Susanna, living in the United States.

Morgenthau in his European Years and Functional Jurisprudence

Morgenthau completed his doctoral dissertation in Germany in the late 1920s which was published in 1929 as his first book entitled, The International Administration of Justice, Its Essence and Its Limits.[17] Following its publication his book received a published review written by Carl Schmitt who was then a jurist teaching at the University of Berlin. Morgenthau relates in his autobiographical writings that despite initially anticipating meeting Schmitt while on a visit to Berlin, the meeting went horribly astray and Morgenthau left his one and only meeting with Schmitt thinking that he had been in the presence of, in his own words, "the demonic." Although such strong wording would normally be guarded in scholarly reception, Morgenthau stated it in his autobiographical writings written near the end of his life in 1980 after nearly fifty years of hindsight and reflection.[18] By the late 1920s Schmitt was becoming the leading jurist for the rising National Socialist movement in Germany and Morgenthau came to see their positions as irreconcilable.

Following this, Morgenthau departed from Germany to complete his Habilitation dissertation (licence to teach at Universities) in Geneva which resulted in his first book written in French being published entitled, The Reality of Norms and in Particular the Norms of International Law: Foundations of a Theory of Norms.[19] By remarkable good fortune Hans Kelsen had also just arrived in Geneva as a Professor and became an adviser to Morgenthau's dissertation. Kelsen was among the strongest critics of Carl Schmitt because Schmitt was advocating for the priority of the political concerns of the state over the adherence by the state to the rule of law. Morgenthau and Kelsen were united against this National Socialist school of political interpretation which down-played the rule of law, and they became lifelong colleagues even after both had emigrated from Europe to take their respective academic positions in the United States.

In 1933, Morgenthau wrote a second short book in French titled The Concept of the Political which was translated into English in 2012.[20] In this book Morgenthau sought to articulate the difference between legal disputes between nations and political disputes between nations or other litigants. For Morgenthau in this book there are four introductory questions which drive this inquiry; (i) Who holds legal power over any of the given objects or concerns being disputed, (ii) In what manner can the holder of this legal power be changed or held accountable; (iii) How can a dispute, the object of which concerns a legal power, be resolved; and (iv) Finally, in what manner will the holder of the legal power be protected in the course of excerizing this power. The end goal of any legal system in this context for Morgenthau is to "ensure justice and peace," always based on the legal principle of rebus sic stantibus, that is, that the standing law must be respected and deferred to.

Morgenthau sought in the 1920s and 1930s a realist alternative to mainstream international law, a quest for "functional jurisprudence". He borrowed ideas from Sigmund Freud,[21] Max Weber, Roscoe Pound and others. Specifically regarding Freud,[22] Morgenthau would later only return to him in his 1946 book on science, and again in 1977 in a co-authored essay with Ethel Person.

Morgenthau in his American Years and Political Realism

Hans Morgenthau is considered one of the "founding fathers" of the realist school in the 20th century. This school of thought holds that nation-states are the main actors in international relations and that the main concern of the field is the study of power. Morgenthau emphasized the importance of "the national interest", and in Politics Among Nations he wrote that "the main signpost that helps political realism to find its way through the landscape of international politics is the concept of interest defined in terms of power".

American Years Up To Politics Among Nations (1948)

In 1940 Morgenthau set out a research program for legal functionalism in the article "Positivism, Functionalism, and International Law". As later manifested in his book Politics Among Nations from 1948 Morgenthau started to enhance the functionalist program as he began to expand his perspective on international law after the Second World War. Francis Boyle has offered the opinion that Morgenthau's post-war writings had perhaps partially contributed towards a "break between international political science and international legal studies".[23] Boyle's opinion is, however, difficult to maintain in the presence of Morgenthau having written and edited a separate constructive chapter on the subject of "International Law" in his book, Politics Among Nations, throughout its five editions between 1948 and his death in 1980.

Recent scholarly assessments of Morgenthau show that his intellectual trajectory was more complicated than originally thought.[24] His realism was infused with moral considerations, and during the last part of his life he favored supranational control of nuclear weapons and strongly opposed the U.S. role in the Vietnam War.[25] His book Scientific Man versus Power Politics (1946) argued against an overreliance on science and technology as solutions to political and social problems.

Starting with the second edition of Politics Among Nations, Morgenthau included a section in the opening chapter called "Six Principles of Political Realism".[26]

The principles, paraphrased, are:

- Political realism believes that politics, like society in general, is governed by objective laws that have their roots in human nature.[27]

- The main signpost of political realism is the concept of interest defined in terms of power, which infuses rational order into the subject matter of politics, and thus makes the theoretical understanding of politics possible. Political realism avoids concerns with the motives and ideology of statesmen. Political realism avoids reinterpreting reality to fit the policy. A good foreign policy minimizes risks and maximizes benefits.

- Realism recognizes that the determining kind of interest varies depending on the political and cultural context in which foreign policy, not to be confused with a theory of international politics, is made. It does not give "interest defined as power" a meaning that is fixed once and for all.

- Political realism is aware of the moral significance of political action. It is also aware of the tension between the moral command and the requirements of successful political action. Realism maintains that universal moral principles must be filtered through the concrete circumstances of time and place, because they cannot be applied to the actions of states in their abstract universal formulation.[28]

- Political realism refuses to identify the moral aspirations of a particular nation with the moral laws that govern the universe.[29]

- The political realist maintains the autonomy of the political sphere; the statesman asks "How does this policy affect the power and interests of the nation?" Political realism is based on a pluralistic conception of human nature. The political realist must show where the nation's interests differ from the moralistic and legalistic viewpoints.

American Years After Politics Among Nations (1948) Up To 1965

Morgenthau was a strong supporter of the Roosevelt[30] and Truman administrations from the war years.[31] When the Eisenhower administration gained the White House, Morgenthau turned his efforts towards a large amount of writing for journals and the press in general. By the time of the Kennedy elections, he had become a consultant to the Kennedy administration until Kennedy's death.[32] When the Johnson administration took control, Morgenthau became much more vocal in his dissent concerning American participation in the Viet-Nam war,[33] for which he was dismissed as a consultant to the Johnson administration in 1965.[4] This debate with Morgenthau has been related in the memoirs of both policy advisors McGeorge Bundy[34] and Walt Rostow,[35] as well as in the biography on McGeorge Bundy by Kai Bird.[36] Morgenthau's dissent concerning American involvement in Vietnam continued to draw attention to him as a scholar of geopolitics for at least a decade after his involvement as advisor to both Kennedy and Johnson, drawing more public attention to himself even than the writing of his magnum opus in Politics Among Nations. This was evidenced by both his public speaking engagements and his appearances on television and the journalistic mass media covering the progress of the Vietnam War well into the years of the Nixon administration.

Aside from his writing of Politics Among Nations, Morgenthau continued with a prolific writing career and published the three volume collection of his wrtings in 1962. Volume One was entitled The Decline of Democratic Politics, Volume Two was The Impasse of American Politics, and Volume Three was The Restoration of American Politics. Each of these volumes itself was the approximate size of his magnum opus of Politics Among Nations and remains a reminder of his vast activities after the end of World War Two.

Morgenthau is sometimes referred to as a classical realist or modern realist in order to differentiate his approach from the structural realism or neo-realism associated with Kenneth Waltz.[37] When neorealism came under increasing criticism in the 1990s, a revival of interest in Moregenthau occurred, most recently seen in the writings of Martti Koskeniemmi in his book on Lauterpacht[38] and Oliver Jutersonke[39] in his essay about Morgenthau.

Morgenthau in his American Years After 1965

Morgenthau's notable book Truth and Power was published in 1970,[40] in which he recalled his dissent towards the Vietnam war, and his significant contributions to the political debate in the United States largely after 1960 at both the domestic and international level. It was dedicated by Morgenthau to Hans Kelsen "who has taught us through his example how to speak Truth to Power." His last major book was dedicated to his colleague Reinhold Niebuhr and was entitled Science: Servant or Master, in 1972. The exact dates of when Morgenthau actually wrote his manuscript on Abraham Lincoln are unknown though it was published posthumously in 1983 together with a separate text by another author.[41]

In the Summer of 1978, Morgenthau wrote his last co-authored essay titled "The Roots of Narcissism," with Ethel Person of Columbia University.[42] This essay was a continuation of Morgenthau's earlier study of this subject in his 1962 essay titled "Public Affairs: Love and Power," where Morgenthau engaged some of the prominent themes which Niebuhr and Tillich were struggling with at that time in their respective academic positions in New York City.[43] More recently, Anthony Lang has managed to recover and have published one of Morgenthau's extensive course notes lectures on Aristotle as a stand-alone book on this subject which Morgenthau taught while at the New School for Social Research during his New York years.[44] The comparison of Morgenthau to Aristotle has been further explored by Molloy in his recent essay on Aristotle and Epicurus.[45]

Following 1965, Morgenthau had become a leading authority and voice in the discussion of just-war theory in the modern nuclear ear.[46] Until Niebuhr's death, the two of them had both carried the discussion of just-war theory into its twentieth century realities. These efforts on behalf of understanding and disseminating the realities of just-war theory would then be continued in the efforts and scholarship of such leading scholars as Michael Walzer and others.[47]

Reception—Critics—Reaction

There were three phases in the recurrent Reception-Critics-Reaction cycle of commentary and interpretations which had a sizable effect upon the discussion and assimilation of Morgenthau's writings for both academic and politically practical applications. The first phase was that which occurred during Morgenthau's own lifetime up to his death in 1980. The second phase of the discussion of his writings and contributions to the study of international politics and international law was between 1980 and up to the one hundred year commemoration from his birth with took place in 2004. The third phase of the reception of his writings was between this centenary commemoration up to the present time, which continues to show a vibrant reception of his continuing influence.[48]

Criticism and Reception During Morgenthau's European Years

In his very early career from the 1920s, the book review of Carl Schmitt regarding Morgenthau's dissertation had a lasting and negative effect on Morgenthau from the 1920s to the end of his life. Schmitt had become a leading juristic voice for the rising national socialist movement in Germany and Morgenthau came to see their positions as incommensuarable in any practical way. Within five years of this, Morgenthau met Hans Kelsen at Geneva while still studying and Kelsen's treatment of Morgenthau's writings left a lifelong positive impression upon the young Morgenthau which he would not forget throughout his lifetime. Kelsen, in the 1920s, had emerged as Schmitt's most thorough critic and had earned himself a reputation as a leading international critic of the then rising national socialist movement in Germany, which was a perfect match for Morgenthau's own negative opinion of national socialism.

Criticism and Reception During Morgenthau's American Years

It continues to be remarkable to note the extent of the widespread infuence which Morgenthau's book Politics Among Nations (1947) would have upon an entire generation of scholars in global politics and international law.[49] The book, in its five editions during Morgenthau's own lifetime, held a position of such prominence for its originality that virtually all scholars for an entire generation needed to take a position concerning its major topics whether positive or negative. Prior to Morgenthau's book, the topics associated today with the field of International Relations were discussed under the separate headings of either International Law or the History of International Affairs. After Morgenthau's book, the field of International Relations was formally accepted as a discipline in its own rights with Universities and Colleges beginning to formally found entire departments and degree programs for the first time with this specific designation, where previously only degrees in either International Law or History of International Affairs were available.

Perhaps foremost of the scholars, in the late 1950s, at least partially critical of Morgenthau was the then young scholar Kenneth Waltz from Berkeley University who contested the influence which Morgenthau had ascribed to the human element of diplomacy concerning the dynamics of global politics.[50] Waltz felt that this element needed to be significantly discounted for the perception of its influence. Waltz would become a leading voice in the movement called neorealism until he passed away in 2013. With emphasis, Waltz would insist that structural influences of state structure exceeded the influence exerted by diplomats and statesmen in explicating matters of state and politics on both the domestic and international level of political analysis, in distinction from the position which Morgenthau was advocating.

Almost simultaneously with Kenneth Waltz's publication of his book on neorealism, Henry Kissinger had also published his own book[51] on the theoretical possibility of limited nuclear war in the late 1950s.[52] The discussion between Morgenthau and Kissinger would revive on and off over the years as Kissinger began to take an active part in consultation to the Rockefeller administration in New York State after his graduation.[53] An archive of some correspondence between the two is on file at the Morgenthau archive in Washington D.C.[54] Although Kissinger was to become a prominent figure in Republican national politics and Morgenthau was inclined towards democratic sympathies ever since the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, the two had continued to meet at various academic and social functions after Morgenthau relocated to New York from Chicago during the last decade of his life through the 1970s.

In a somewhat prescient display of insight, Morgenthau in 1977 wrote a brief "Foreward" on the theme of terrorism as it began to emerge in the 1970s, mostly in the form of hijacking of airlines at that time.[55] Yonah Alexander, the editor of that volume on terrorism, was then a young scholar well before the current dilemmas of terrorism in the era following 9/11, and the Morgenthau "Foreward" to Alexander's book was a courtesy that Morgenthau had extended only on a limited number of occasions in his lifetime.

Among the many issues which came to concern Morgenthau during his lifetime, he was joined by Hannah Arendt in a special dedication of his time and efforts to the support of the birth and growth of the state of Israel after its creation following WWII. Both Morgenthau and Arendt had spent much time in making annual trips to Israel to assist Israel by lending their established academic voices to its still young and growing academic community during its inaugural decades as a new modern nation.[56]

Criticism and Reception of Morgenthau's Legacy

The English language reception of Morgenthau was considerably enhanced through the publication of Morgenthau's short biography by Christoph Frei in 2001 translated into English[57] based upon the original German language publication of the book in 1991 with an emphasis on his student years (see Bibliography below).[58] This was supplemented in the German language by an even more comprehensive biography on Morgenthau by Christoph Rohde in 2004 still only available in the German language.[59] In 2004, no less than three full length commemorative volumes[60] were published on Morgenthau's vast influence on geopolitics over the years by many of the leading contemporary scholars of the day[61] (see Further Reading section below.) John Gaddis and Campbell Craig have together taken a guarded position concerning the reception of both Morgenthau and Waltz.[62] Another of the guarded positions, generally favorable, taken on Morgenthau after his death was that of Stanley Hoffman of Harvard University.[63] A somewhat speculative account[64] trying to tie Thucydides to Morgenthau was published in 2003 by Ned Lebow,[65] even though Morgenthau himself did not explore his larger or lesser relationship to Thucydides.

In the tradition of Kenneth Waltz and defensive neorealism,[66] John Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago has studied the relationship of Morgenthau's political realism in comparison with the neo-conservativism prevailing during the Bush Administration of 2003 in the context of the Iraq war.[67] Mearsheimer's general position of offensive neorealism has on other issues come into conflict, for example, with Morgenthau's strong endorsement concerning the creation and support for Israel[68][69] as an enduring nation. This contrast was evidenced in Mearsheimer's co-authored book with Steven Walt of Harvard University titled The Israel Lobby.[70] For Morgenthau, the ethical and moral component of international politics was on the whole, and unlike the positions of either defensive neorealism or offensive neorealism, an integral part of the reasoning process of both the international statesman and the essential content of responsible scholarship in international relations.[71]

Benjamin Mollov has presented a book in which the second half covers Morgenthau's strong connection to his Jewish origins and his support for the emerging state of Israel up until the end of his life in 1980.[72] Regarding his religious affiliations and duties, Morgenthau is also known to have taken his son to religious services while at the University of Chicago at the congregation located across the street from the church where, prior to his presidency, President Obama had attended church with his family. A broad range of topics in geopolitics continue to appear in the press[73] as recently as 2013 of new books[74] dealing with Morgenthau's influence upon contemporary theory and practice in international politics and international law (see Further Reading section below.)

Bibliography

- Scientific Man versus Power Politics (1946) Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace (1948) New York NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- In Defense of the National Interest (1951) New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- The Purpose of American Politics (1960) New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Crossroad Papers: A Look Into the American Future (ed.) (1965) New York, NY: Norton.

- Truth and Power: Essays of a Decade, 1960–70 (1970) New York, NY: Praeger.

- Essays on Lincoln's Faith and Politics. (1983) Lanham, MD: Univ. Press of America for the Miller Center of Public Affairs at the Univ. of Virginia. Co-published with a separate text by David Hein.

For a complete list of Morgenthau's writings, see "The Hans J. Morgenthau Page"

See also

- Morgenthau Lectures by the Carnegie Council

- E. H. Carr

- Kenneth W. Thompson

- Henry Kissinger

- Stephen Walt

- John Mearsheimer

- Committee on International Relations at the University of Chicago

References

- ^ Rice, Daniel. Reinhold Niebuhr and His Circle of Influence, University of Cambridge Press, 2013, complete chapter on Hans Morgenthau.

- ^ Rice, Daniel. Reinhold Niebuhr and His Circle of Influence, University of Cambridge Press, 2013, complete chapter on George Kennan.

- ^ Klusmeyer, Douglas. "Beyond Tragedy: Hannah Arendt and Hans Morgenthau on Responsibility, Evil and Political Ethics." International Studies Review 11, no.2 (2009): 332–351.

- ^ a b Zambernardi, L. (2011). "The Impotence of Power: Morgenthau's Critique of American Intervention in Vietnam". Review of International Studies. 37 (3): 1335–1356. doi:10.1017/S0260210510001531.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1982). In Defense of the National Interest: A Critical Examination of American Foreign Policy, with a new introduction by Kenneth W. Thompson (Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1982).

- ^ Neacsu, Mihaela. Hans J. Morgenthau's Theory of International Relations: Disenchantment and Re-Enchantment. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- ^ Turner, Stephen, and G.O. Mazur. "Morgenthau as a Weberian Methodologist." European Journal of International Relations 15, no. 3 (2009): 477–504.

- ^ Bell, Duncan, ed. Political Thought and International Relations: Variations on a Realist Theme. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- ^ Tsou, Tang. America's Failure in China, 1941–50.

- ^ Leo Baeck Institute. Hans Morgenthau Archive Files. New York, New York.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1976). “Hannah Arendt, 1906-1975,” Political Theory, vol. 4, no. 1 (February 1976), pp. 5-8.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1977). “Hannah Arendt on Totalitarianism and Democracy,” Social Research, vol. 44, no. 1 (Spring 1977), pp. 127-131.

- ^ Young-Bruehl, Elizabeth. Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World, Second Edition, Yale University Press, 2004.

- ^ Mazur, G.O., ed. One Hundred Year Commemoration to the Life of Hans Morgenthau. New York: Semenenko, 2004.

- ^ Small amount of plutonium missing from crashed jet

- ^ Hans Morgenthau dies; noted political scientist

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans. Die internationale Rechtspflege, ihr Wesen und ihre Grenzen, in the Frankfurter Abhandlungen zum Kriegsverhütungsrecht book series (Leipzig: Universitätsverlag Noske, 1929), still untranslated into English.

- ^ “Fragment of an Intellectual Autobiography: 1904-1932,” in Kenneth W. Thompson and Robert J. Myers, eds., Truth and Tragedy: A Tribute to Hans J. Morgenthau (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1984).

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans. La Réalité des normes en particulier des normes du droit international: Fondements d’une théorie des normes, (Paris: Alcan, 1934), still untranslated into English.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (2012). The Concept of the Political, Palgrave Press, translated from the French, La notion du "politique", from 1933.

- ^ Schuett, Robert. "Freudian Roots of Political Realism: The Importance of Sigmund Freud to Hans J. Morgenthau's Theory of International Power Politics." History of the Human Sciences 20, no. 4 (2007): 53–78.

- ^ Schuett, Robert. Political Realism, Freud, and Human Nature in International Relations: The Resurrection of the Realist Man. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans J., Positivism, Functionalism, and International Law, American Journal of International Law, vol 34, 2 (1940): 260–284; Scheuerman, William E., A theoretical missed opportunity? Hans J. Morgenthau as Critical Realist, Bell, Duncan (Ed.), Political Thought and International Relations: Variations on a Realist Theme, 2008; Boyle, Francis, "World Politics and International Law, p. 12

- ^ William E. Scheuerman, Hans Morgenthau: Realism and Beyond (Polity Press, 2009); Michael C. Williams, ed., Reconsidering Realism: The Legacy of Hans J. Morgenthau (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007); Christoph Frei, Hans J. Morgenthau: An Intellectual Biography (LSU Press, 2001).

- ^ E.g.: Hans J. Morgenthau, "We Are Deluding Ourselves in Viet-Nam", New York Times Magazine, April 18, 1965, reprinted in The Viet-Nam Reader, ed. M. Raskin and B. Fall (Vintage Books, 1967), pp. 37–45.

- ^ Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, Fifth Edition, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978, pp. 4–15.

- ^ Russell, Greg. Hans J. Morgenthau and the Ethics of American Statecraft. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990.

- ^ Cozette, Murielle. "Reclaiming the Critical Dimension of Realism: Hans J. Morgenthau on the Ethics of Scholarship." Review of International Studies 34 (2008): 5–27.

- ^ Murray, A. J. H. "The Moral Politics of Hans Morgenthau." The Review of Politics 58, no. 1 (1996): 81–107.

- ^ Scheuerman, William E. Hans Morgenthau: Realism and Beyond. Cambridge: Polity, 2009.

- ^ Scheuerman, William E. "Realism and the Left: The Case of Hans J. Morgenthau." Review of International Studies 34 (2008): 29–51.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1975). "The Intellectual, Political, and Moral Roots of U. S. Failure in Vietnam,” in William D. Coplin and Charles W. Kegley, Jr., eds., Analyzing International Relations: A Multimethod Introduction (New York: Praeger, 1975).

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1975). “The Real Issue for the U.S. in Cambodia,” The New Leader, vol. 58, issue 6 (March 17, 1975), pp. 4-6.

- ^ Goldstein, Gordon. Lessons in Disaster: McGeorge Bundy and the Path to War in Vietnam, 2009.

- ^ Milne, David. America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War, 2009.

- ^ Bird, Kai. The Color of Truth: McGeorge Bundy and William Bundy: Brothers in Arms, Simon and Schuster, 2000.

- ^ Cf. Jack Donnelly, Realism and International Relations (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000), pp. 11–12, though he prefers the label "biological realist" to "classical realist". For an argument that the differences between classical and structural realists have been exaggerated, see Parent, Joseph M.; Baron, Joshua M. (2011). "Elder Abuse: How the Moderns Mistreat Classical Realism". International Studies Review. 13 (2): 192–213. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2486.2011.01021.x.

- ^ Koskenniemi, Martti. The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law 1870-1960 (Hersch Lauterpacht Memorial Lectures).

- ^ Jütersonke, Oliver. "Hans J. Morgenthau on the Limits of Justiciability in International Law." Journal of the History of International Law 8, no. 2 (2006): 181–211.

- ^ Myers, Robert J. "Hans J. Morgenthau: On Speaking Truth to Power." Society 29, no. 2 (1992): 65–71.

- ^ “The Mind of Abraham Lincoln: A Study in Detachment and Practicality,” in Kenneth W. Thompson, ed., Essays on Lincoln’s Faith and Politics (Lanham: University Press of America, 1983), pp. 3-104.

- ^ Hans Morgenthau and Ethel Person (1978). "The Roots of Narcissism," The Partisan Review, pp 337–347, Summer 1978.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1962). "Public Affairs: Love and Power," Commentary 33:3 (March 1962): 248.

- ^ Lang, Anthony F., Jr., ed. Political Theory and International Affairs: Hans J. Morgenthau on Aristotle's The Politics. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004.

- ^ Molloy, Sean. "Aristotle, Epicurus, Morgenthau and the Political Ethics of the Lesser Evil." Journal of International Political Theory 5 (2009): 94–112.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1978). “Vietnam and Cambodia,” (Exchange with Noam Chomsky and Michael Walzer) Dissent, vol. 25 (Fall 1978), pp. 386-391.

- ^ Morgenthau, "Vietnam and Cambodia."

- ^ Bain, William. "Deconfusing Morgenthau: Moral Inquiry and Classical Realism Reconsidered." Review of International Studies 26, no. 3 (2000): 445–64.

- ^ Guilhot, Nicolas. "The Realist Gambit: Postwar American Political Science and the Birth of IR Theory." International Political Sociology 4, no. 2 (2008):281–304.

- ^ Behr, Hartmut, and Amelia Heath. "Misreading in IR Theory and Ideology Critique: Morgenthau, Waltz and Neo-Realism." Review of International Studies 35 (2009): 327–49.

- ^ Kissinger, Henry (1957). Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy. ISBN 0-86531-745-3 (1984 edition)

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1977). “The Fallacy of Thinking Conventionally about Nuclear Weapons,” in David Carlton and Carlo Schaerf, eds., Arms Control and Technological Innovation (London: Croom Helm, 1977).

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1977). “The Fallacy of Thinking Conventionally about Nuclear Weapons,” in David Carlton and Carlo Schaerf, eds., Arms Control and Technological Innovation (London: Croom Helm, 1977).

- ^ Morgenthau Archives. Library of Congress.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1977). “Foreword,” in Yonah Alexander and Seymour Maxwell Finger, eds., Terrorism: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977).

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1975). “Address Delivered by Professor Hans Morgenthau at the Inauguration Ceremony of the Reuben Hecht Chair of Zionist Studies at the University of Haifa,” (May 13, 1975) MS in HJMP, Container No. 175.

- ^ Frei, Christoph. Hans J. Morgenthau: An Intellectual Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

- ^ Peterson, Ulrik. "Breathing Nietzsche's Air: New Reflections on Morgenthau's Concept of Power and Human Nature." Alternatives 24, no. 1 (1999): 83–113.

- ^ Hans J. Morgenthau und der weltpolitische Realismus (German Edition): Die Grundlegung einer realistischen Theorie. P. Weidmann und Christoph Rohde von VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften (16. Februar 2004).

- ^ Hacke, Christian, Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, and Kai M. Schellhorn, eds. The Heritage, Challenge, and Future of Realism: In Memoriam Hans J. Morgenthau (1904–1980). Göttingen, Germany: V&R unipress, 2005.

- ^ Mazur, G.O., ed. Twenty-Five Year Memorial Commemoration to the Life of Hans Morgenthau. New York: Semenenko Foundation, Andreeff Hall, 12, rue de Montrosier, 92200 Neuilly, Paris, France, 2006.

- ^ Craig, Campbell. Glimmer of a New Leviathan: Total War in the Realism of Niebuhr, Morgenthau, and Waltz. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

- ^ Hoffmann, Stanley. "Hans Morgenthau: The Limits and Influence of 'Realism'." In Janus and Minerva. Boulder, CO.: Westview, 1987, pp. 70–81.

- ^ Pin-Fat, V. "The Metaphysics of the National Interest and the 'Mysticism' of the Nation-State: Reading Hans J. Morgenthau." Review of International Studies 31, no. 2 (2005): 217–36.

- ^ Lebow, Richard Ned. The Tragic Vision of Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ^ Waltz, Kenneth (1959). Man, the State, and War, 1959.

- ^ Mearsheimer, John J. "Hans Morgenthau and the Iraq War: Realism Versus Neo-Conservatism." openDemocracy.net (2005).

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1979). Human Rights and Foreign Policy (New York: Council on Religion and International Affairs, 1979).

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (1977). “The Threat to Israel’s Security,” The New Leader, vol. 60, issue 6 (March 14, 1977), pp. 7-9.

- ^ Mearsheimer, John J. and Walt, Stephen (2007). The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-17772-4.

- ^ Zambernardi, Lorenzo. I limiti della potenza. Etica e politica nella teoria internazionale di Hans J. Morgenthau. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2010.

- ^ Mollov, M. Benjamin. Power and Transcendence: Hans J. Morgenthau and the Jewish Experience. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002.

- ^ Conces, Rory J. "Rethinking Realism (or Whatever) and the War on Terrorism in a Place Like the Balkans." Theoria 56 (2009): 81–124.

- ^ Rice, Daniel. Reinhold Niebuhr and His Circle of Influence, University of Cambridge Press, 2013.

Further reading

- Bain, William. "Deconfusing Morgenthau: Moral Inquiry and Classical Realism Reconsidered." Review of International Studies 26, no. 3 (2000): 445–64.

- Behr, Hartmut, and Amelia Heath. "Misreading in IR Theory and Ideology Critique: Morgenthau, Waltz and Neo-Realism." Review of International Studies 35 (2009): 327–49.

- Bell, Duncan, ed. Political Thought and International Relations: Variations on a Realist Theme. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Bird, Kai. The Color of Truth: McGeorge Bundy and William Bundy: Brothers in Arms, Simon and Schuster, 2000.

- Conces, Rory J. "Rethinking Realism (or Whatever) and the War on Terrorism in a Place Like the Balkans." Theoria 56 (2009): 81–124.

- Cozette, Murielle. "Reclaiming the Critical Dimension of Realism: Hans J. Morgenthau on the Ethics of Scholarship." Review of International Studies 34 (2008): 5–27.

- Craig, Campbell. Glimmer of a New Leviathan: Total War in the Realism of Niebuhr, Morgenthau, and Waltz. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

- Donnelly, Jack. Realism and International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Frei, Christoph. Hans J. Morgenthau: An Intellectual Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

- Gellman, Peter. "Hans J. Morgenthau and the Legacy of Political Realism." Review of International Studies 14 (1988): 247–66.

- Goldstein, Gordon. Lessons in Disaster: McGeorge Bundy and the Path to War in Vietnam, 2009.

- Griffiths, Martin. Realism, Idealism and International Politics. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Guilhot, Nicolas. "The Realist Gambit: Postwar American Political Science and the Birth of IR Theory." International Political Sociology 4, no. 2 (2008):281–304.

- Hacke, Christian, Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, and Kai M. Schellhorn, eds. The Heritage, Challenge, and Future of Realism: In Memoriam Hans J. Morgenthau (1904–1980). Göttingen, Germany: V&R unipress, 2005.

- Hoffmann, Stanley. "Hans Morgenthau: The Limits and Influence of 'Realism'." In Janus and Minerva. Boulder, CO.: Westview, 1987, pp. 70–81.

- Jütersonke, Oliver. "Hans J. Morgenthau on the Limits of Justiciability in International Law." Journal of the History of International Law 8, no. 2 (2006): 181–211.

- Klusmeyer, Douglas. "Beyond Tragedy: Hannah Arendt and Hans Morgenthau on Responsibility, Evil and Political Ethics." International Studies Review 11, no.2 (2009): 332–351.

- Koskenniemi, Martti. The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law 1870-1960 (Hersch Lauterpacht Memorial Lectures).

- Lang, Anthony F., Jr., ed. Political Theory and International Affairs: Hans J. Morgenthau on Aristotle's The Politics. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004.

- Lebow, Richard Ned. The Tragic Vision of Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Little, Richard. The Balance of Power in International Relations: Metaphors, Myths and Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Mazur, G.O., ed. One Hundred Year Commemoration to the Life of Hans Morgenthau. New York: Semenenko, 2004.

- Mazur, G.O., ed. Twenty-Five Year Memorial Commemoration to the Life of Hans Morgenthau. New York: Semenenko Foundation, Andreeff Hall, 12, rue de Montrosier, 92200 Neuilly, Paris, France, 2006.

- Mearsheimer, John J. "Hans Morgenthau and the Iraq War: Realism Versus Neo-Conservatism." openDemocracy.net (2005).

- Mearsheimer, John J. and Walt, Stephen (2007). The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-17772-4.

- Milne, David. America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War, 2009.

- Mollov, M. Benjamin. Power and Transcendence: Hans J. Morgenthau and the Jewish Experience. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002.

- Molloy, Sean. "Aristotle, Epicurus, Morgenthau and the Political Ethics of the Lesser Evil." Journal of International Political Theory 5 (2009): 94–112.

- Molloy, Sean. The Hidden History of Realism: A Genealogy of Power Politics. New York: Palgrave, 2006.

- Murray, A. J. H. "The Moral Politics of Hans Morgenthau." The Review of Politics 58, no. 1 (1996): 81–107.

- Myers, Robert J. "Hans J. Morgenthau: On Speaking Truth to Power." Society 29, no. 2 (1992): 65–71.

- Neacsu, Mihaela. Hans J. Morgenthau's Theory of International Relations: Disenchantment and Re-Enchantment. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- Peterson, Ulrik. "Breathing Nietzsche's Air: New Reflections on Morgenthau's Concept of Power and Human Nature." Alternatives 24, no. 1 (1999): 83–113.

- Pin-Fat, V. "The Metaphysics of the National Interest and the 'Mysticism' of the Nation-State: Reading Hans J. Morgenthau." Review of International Studies 31, no. 2 (2005): 217–36.

- Rice, Daniel. Reinhold Niebuhr and His Circle of Influence, University of Cambridge Press, 2013.

- Rohde, Christoph. Hans J. Morgenthau und der weltpolitische Realismus (German Edition): Die Grundlegung einer realistischen Theorie. P. Weidmann und Christoph Rohde von VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften (16. Februar 2004)

- Russell, Greg. Hans J. Morgenthau and the Ethics of American Statecraft. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990.

- Scheuerman, William E. Hans Morgenthau: Realism and Beyond. Cambridge: Polity, 2009.

- Scheuerman, William E. "Realism and the Left: The Case of Hans J. Morgenthau." Review of International Studies 34 (2008): 29–51.

- Schuett, Robert. "Freudian Roots of Political Realism: The Importance of Sigmund Freud to Hans J. Morgenthau's Theory of International Power Politics." History of the Human Sciences 20, no. 4 (2007): 53–78.

- Schuett, Robert. Political Realism, Freud, and Human Nature in International Relations: The Resurrection of the Realist Man. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Shilliam, Robbie. "Morgenthau in Context: German Backwardness, German Intellectuals and the Rise and Fall of a Liberal Project." European Journal of International Relations 13, no. 3 (2007): 299–327.

- Smith, Michael J. Realist Thought from Weber to Kissinger. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986.

- Thompson, Kenneth W., and Robert J. Myers, eds. Truth and Tragedy: A Tribute to Hans J. Morgenthau. augmented ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1984.

- Tickner, J. Ann. "Hans Morgenthau's Principles of Political Realism: A Feminist Reformulation." Millennium: Journal of International Studies 17, no.3 (1988): 429–40.

- Tjalve, Vibeke Schou. Realist Strategies of Republican Peace: Niebuhr, Morgenthau, and the Politics of Patriotic Dissent. New York: Palgrave, 2008.

- Tsou, Tang. America's Failure in China, 1941–50.

- Turner, Stephen, and G.O. Mazur. "Morgenthau as a Weberian Methodologist." European Journal of International Relations 15, no. 3 (2009): 477–504.

- Williams, Michael C., ed. Realism Reconsidered: The Legacy of Hans Morgenthau in International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Williams, Michael C. The Realist Tradition and the Limits of International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Williams, Michael C. "Why Ideas Matter in International Relations: Hans Morgenthau, Classical Realism, and the Moral Construction of Power Politics." International Organization 58 (2004): 633–65.

- Wong, Benjamin. "Hans Morgenthau's Anti-Machiavellian Machiavellianism." Millennium: Journal of International Studies 29, no. 2 (2000): 389–409.

- Young-Bruehl, Elizabeth. Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World, Second Edition, Yale University Press, 2004.

- Zambernardi, Lorenzo. I limiti della potenza. Etica e politica nella teoria internazionale di Hans J. Morgenthau. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2010.

Further Reading II (Hans Morgenthau Chronology)

- “Die Völkerrechtlichen Ergebnisse der Tagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Völkerrecht,” Die Justiz: Zeitschrift für Erneuerung des Deutschen Rechtswesens, Jg. 4, H. 6 (August 1928), S. 621-624.

- Die internationale Rechtspflege: Ihr Wesen und ihre Grenzen (Leipzig: Robert Noske, 1929).

- “Stresemann als Schöpfer der deutschen Völkerrechtspolitik,” Die Justiz: Zeitschrift für Erneuerung des Deutschen Rechtswesens, Jg. 5, H. 3 (1929), S. 169-176.

- “Über die Herkunft des Politischen aus dem Wesen des Menschen,” (Frankfurt am Main, 1930) MS in HJMP, Container No. 151 and 199.

- “Der Selbstmord mit gutem Gewissen: Zur Kritik des Pazifismus und der neuen deutschen Kriegsphilosophie,” (Frankfurt am Main, 1930) MS in HJMP, Container No. 96.

- “Der Kampf der deutschen Staatslehre um die Wirklichkeit des Staats,” MS der Antirittsvorlesung an der Universität Geneva (1932) in HJMP, Container No. 110.

- “Einige logische Bemerkungen zu Carl Schmitts Begriff des Politischen,” (Geneva: o. J. [1932]) MS in HJMP, Container No. 110.

- La Notion du ‘politique’ et la théorie des différends internationaux (Paris: Recueil Sirey, 1933).

- “Die Wirklichkeit des Völkerbunds,” Neue Zürcher Zeitung (2. April, 1933), Blatt 3.

- La Réalité des normes en particulier des normes du droit international: Fondements d’une théorie des normes (Paris: Alcan, 1934).

- “Über den Sinn der Wissenschaft in dieser Zeit und über die Bestimmung des Menschen,” (Geneva, 1934) MS in HJMP, Container No. 151.

- “Théorie des sanctions internationales,” Revue de droit international et de législation comparée, vol. 16, no. 3 (1935), pp. 474-503 et no. 4 (1935), pp. 809-836.

- “Die Entstehung der Normentheorie aus dem Zusammenbruch der Ethik: Eine Untersuchung über die geistesgeschichtlichen Voraussetzungen der Normentheorie,” (Geneva, 1935) MS in HJMP, Container No. 112.

- “Die Krise der metaphysischen Ethik von Kant bis Nietzsche,” (Geneva, 1935) MS in HJMP, Container No. 112.

- “Derecho Internacional Publico: Introducción y Conceptos Fundamentales,” (Madrid, 1935) MS in HJMP, Container No. 121.

- Positivisme mal compris et théorie réaliste du droit international, in Collección de Estudios historicos, jurídicos, pedagógicos y literarios, ofrecidas a D. Rafael Altamira y Crevea (Madrid: Bernejo, 1936) [in HJMP, Container No. 96].

- “Das Problem des Rechtssystems,” (Madrid, Bozen, Paris, 1936) MS in HJMP, Container No. 199.

- “Kann in unserer Zeit eine objektive Moralordnung aufgestellt werden? Wenn ja, worauf kann sie gegründet werden?” (Paris, 1937) MS in HJMP 112.

- “Amerikanische Außenpolitik und öffentliche Meinung,” (o. O. [New York?], o. J. [1937?]) MS in HJMP, Container No. 96.

- “Das Problem der amerikanischen Universität,” Neue Zürcher Zeitung (Januar 10, 1938), S. 5 [MS in HJMP, Container No. 110].

- “The End of Switzerland’s ‘Differential’ Neutrality,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 32 (July 1938), pp. 558-562.

- “Plans for Work,” (n. d. [November 1938?]) MS in HJMP, Container No. 31, Folder “John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, 1938-71”.

- “The Problem of Neutrality,” The University of Kansas City Law Review, vol. 7 (February 1939), pp. 109-128.

- “The Resurrection of Neutrality in Europe,” American Political Science Review, vol. 33, no. 3 (June 1939), pp. 473-486.

- “Grandeur and Decadence of Spanish Civilization,” The University Review (Kansas City), vol. 6 (October 1939), pp. 58-63 [DDP, pp. 212-219].

- “Positivism, Functionalism, and International Law,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 34, no. 2 (April 1940), pp. 260-284 [DP, pp. 210-235; DDP, pp. 282-307].

- “Review of Book: Law, the State, and the International Community, by James Brown Scott,” Political Science Quarterly, vol. 55, no. 2 (June 1940), pp. 261-262.

- “Review of Book: An Introduction to the Sociology of Law, by N. S. Timasheff,” The Yale Law Journal, vol. 49, no. 8 (June 1940), pp. 1510-1513.

- “Review of Book: Making International Law Work, by George W. Keeton and Georg Schwarzenberger,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 34, no. 3 (July 1940), p. 537.

- “Review of Book: The Saar Plebiscite, by Sarah Wambaugh,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 34, no. 3 (July 1940), pp. 541-542.

- “Liberalism and Foreign Policy,” Lecture given at the New School for Social Research as Last of Series of Lectures on “Liberalism Today” (August 16, 1940) MS in HJMP, Container No. 168.

- “Report of Progress,” Year Book of the American Philosophical Society 1940 (1941), pp. 224-225.

- “Sociology of Law: Editor’s Foreword,” University of Kansas City Law Review, vol. 9 (1941), pp. 61-62.

- “National Socialist Doctrine of World Organization,” Proceedings of the Seventh Conference of Teachers of International Law and Related Subjects (Washington, 1941) [DDP, pp. 241-246].

- “Liberalism and War,” (1941) MS in HJMP, Container No. 96.

- “Professor Karl Neumeyer,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 35 (October 1941), p. 672.

- “Report of Progress,” Year Book of the American Philosophical Society 1941 (1942), pp. 211-214.

- “Review of Book: Law without Force, by Gerhart Niemeyer,” Iowa Law Review, vol. 27, no. 2 (January 1942), pp. 350-355.

- “Review of Book: Federal Administrative Proceedings, by Walter Gellhorn,” Columbia Law Review, vol. 42, no. 2 (February 1942), pp. 330-333.

- “Review of Book: Power Politics, by Georg Schwarzenberger,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 36, no. 2 (April 1942), pp. 351-352.

- “Constitutional Reform in Missouri,” The University of Kansas City Law Review, vol. 11 (December 1942), pp. 1-2.

- “Report of Progress,” Year Book of the American Philosophical Society 1942 (1943), pp. 188-191.

- “Review of Book: The Guilt of the German Army, by Hans Ernest Fried,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 37, no. 1 (January 1943), pp. 188-189.

- “Review of Book: The Disarmament Illusion, by Merze Tate,” Russian Review, vol. 2, no. 2 (Spring 1943), pp. 104-105.

- “Review of Book: International Labor Conventions, by Conley Hall Dillon,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review and American Law Register, vol. 91, no. 6 (March 1943), pp. 576-578.

- “Implied Regulatory Powers in Administrative Law,” The Iowa Law Review, vol. 28 (May 1943), pp. 575-612 [DP, pp. 123-169; DDP, pp. 134-180].

- “Implied Limitations on Regulatory Powers in Administrative Law,” The University of Chicago Law Review, vol. 11, no. 2 (February, 1944), pp. 91-116.

- “Review of Book: Towards an Abiding Peace, by R. M. MacIver,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 52, no. 1 (March 1944), pp. 91-92.

- “The Limitations of Science and the Problem of Social Planning,” Ethics, vol. 54, no. 3 (April 1944), pp. 174-185.

- “Review of Book: Digest of International Law, by Green Haywood Hackworth,” The University of Chicago Law Review, vol. 11, no. 4 (June 1944), pp. 454-455.

- “Review of Book: The Task of the Law, by Roscoe Pound,” Harvard Law Review, vol. 57, no. 6 (July 1944), pp. 922-926.

- “Review of Book: Were the Minorities Treaties a Failure? by Jacob Robinson, et al.,” Journal of Modern History, vol. 16, No. 3 (September 1944), p. 237.

- “Review of Book: The Decline of Liberalism as an Ideology, by John H. Hallowell,” The Journal of Political Economy, vol. 52, no. 4 (December 1944), p. 364.

- “Review of Book: The Danube Basin and the German Economic Sphere, by Antonín Basch; A Challenge to Peacemakers, ed. by Joseph S. Roucek,” American Political Science Review, vol. 38, no. 6 (December 1944), pp. 1234-1236.

- “The Scientific Solution of the Social Conflicts,” in Lyman Bryson, Louis Finkelstein, and Robert M. MacIver, eds., Approaches to National Unity: Fifth Symposium of the Conference on Science, Philosophy and Religion (New York: Harper, 1945).

- “Introduction,” in Heinrich Hauser, The German Talks Back (New York: H. Holt, 1945) [DDP, pp. 220-226].

- “The Machiavellian Utopia,” Ethics, vol. 55, no. 2 (January 1945), pp. 145-147.

- “Review of Book: War and its Causes, by L. L. Bernard,” American Political Science Review, vol. 39, no. 2 (April 1945), pp. 365-366.

- “Review of Book: The Super-Powers, by William T. R. Fox,” Ethics, vol. 55, no. 3 (April 1945), pp. 227-228.

- “Review of Book: International Tribunals, by Manley O. Hudson,” American Political Science Review, vol. 39, no. 4 (August 1945), pp. 802-804.

- “The Evil of Politics and the Ethics of Evil,” Ethics, vol. 56, no. 1 (October 1945), pp. 1-18.

- “About Cynicism, Perfectionism, and Realism in International Affairs,” Critic, vol. 11 (November 30, 1945), pp. 3-4 [DDP, pp. 127-130].

- “Review of Book: Nationalities and National Minorities, by Oscar I. Janowsky,” Harvard Law Review, vol. 59, no. 2 (December 1945), pp. 301-304 [DDP, pp. 196-200].

- “Review of Book: The Peace Conference of 1919: Organization and Procedure, by F. S. Marston,” American Political Science Review, vol. 39, no. 6 (December 1945), pp. 1212-1213.

- Scientific Man vs. Power Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1946).

- "Preface," in Morgenthau, ed., Peace, Security and the United Nations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1946).

- “Naziism,” in Joseph S. Roucek, ed., Twentieth Century Political Thought (New York: Philosophical Library, 1946) [DDP, pp. 227-240].

- “Review of Book: International Law, Volume 1: International Law as Applied by International Courts and Tribunals, by Georg Schwarzenberger,” The Review of Politics, vol. 8, no. 1 (January 1946), pp. 141-144.

- “The Transformation of Our Contemporary Culture into a Spiritual Culture: As Seen by a Political Scientist,” Paper presented at the Chicago Institute for Religious and Social Studies (February 5, 1946) MS in HJMP, Container No. 168.

- “Review of Book: The Limits of Jurisprudence Defined, by Jeremy Bentham,” Journal of Modern History, vol. 18, no. 1 (March 1946), pp. 77-78.

- “Review of Book: The International Law of the Future; An International Bill of the Rights of Man, by H. Lauterpacht,” The University of Chicago Law Review, vol. 13, no. 3 (April 1946), pp. 400-402.

- “Diplomacy,” Yale Law Journal, vol. 55, no. 5 (August 1946), pp. 1067-1080 [DDP, pp. 342-358].

- “Review of Book: The Device of Government, by John Laird,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 54, no. 6 (December 1946), p. 566.

- “Review of Book: Nationality in History and Politics, by Frederick Hertz,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 54, no. 6 (December 1946), pp. 567-568.

- “Review of Book: Pioneers in World Order, by Harriet Eager Davis,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 54, no. 6 (December 1946), pp. 568-569.

- “Views of Nuremberg: Further Analysis of the Trial and Its Importance,” America (December 7, 1946), pp. 266-267 [DDP, pp. 377-379].

- “Ethics and Politics,” in Lyman Bryson, Louis Finkelstein, and R. M. MacIver, eds., Approaches to Group Understanding: Sixth Symposium of the Conference on Science, Philosophy and Religion (New York: Harper, 1947).

- “The Escape from Power in the Western World,” in Lyman Bryson, Louis Finkelstein, and R. M. MacIver, ed., Conflicts of Power in Modern Culture: Seventh Symposium of the Conference on Science, Philosophy and Religion (New York: Harper, 1947) [DP, pp. 239-245; DDP, pp. 311-317; MS in HJMP, Container No. 176].

- “Review of Book: The Myth of the State, by Ernst Cassirer,” Ethics, vol. 57, no. 2 (January 1947), pp. 141-142.

- “Review of Book: The Process of International Arbitration, by Kenneth S. Carlston,” The University of Chicago Law Review, vol. 14, no. 4 (June 1947), pp. 729-730.

- “Review of Book: Foundations of National Power: Readings on World Politics and American Security, by Harold Sprout and Margaret Sprout,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 55, no. 3 (June 1947), pp. 264-265.

- “Letter to the Editor,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 252 (July 1947), pp. 173-174.

- “Review of Book: The Great Dilemma of World Organization, by Fremont Rider,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 55, no. 4 (August 1947), p. 401.

- “Review of Book: A Free and Responsible Press, by The Commission on Freedom of the Press,” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 53, no. 3 (November 1947), p. 225.

- “Review of Book: Soviet Philosophy, by John Somerville,” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 53, no. 3 (November 1947), p. 228.

- “Review of Book: Man and the State, by William Ebenstein,” American Political Science Review, vol. 41, no. 6 (December 1947), pp. 1209-1210.

- Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace (New York: Knopf, 1948).

- “Review of Book: The Cultural Approach: Another Way in International Relations, ed. by Ruth McMurry and Muna Lee,” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 53, no. 5 (March 1948), pp. 397-398.

- “The Problem of Sovereignty Reconsidered,” Columbia Law Review, vol. 48, no. 3 (April 1948), pp. 341-365.

- “The Twilight of International Morality,” Ethics, vol. 58, no. 2 (January 1948), pp. 79-99.

- “World Politics in the Mid-Twentieth Century,” The Review of Politics, vol. 10 (April 1948), pp. 154-173.

- “Review of Book: The Spanish Story, by Herbert Feis,” American Political Science Review, vol. 42, no. 4 (August 1948), pp. 791-792.

- “The Political Science of E. H. Carr,” World Politics, vol. 1, no. 1 (October 1948), pp. 127-134 [DP, pp. 350-357; RAP, pp. 36-43].

- “Review of Book: La Constitution Fédérale de la Suisse, 1848-1948, by William E. Rappard,” American Political Science Review, vol. 42, no. 6 (December 1948), pp. 1222-1224.

- “Review of Book: The Pattern of Imperialism: A Study in the Theories of Power, by E. M. Winslow,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 56, no. 6 (December 1948), p. 543.

- “Review of Book: States and Morals: A Study in Political Conflicts, by T. D. Weldon,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 56, no. 6 (December 1948), p. 553.

- “The Conduct of American Foreign Policy,” Parliamentary Affairs, vol. 3 (Winter 1949), pp. 147-161.

- “Review of Book: Modern Nationalism and Religion, by Salo Wittmayer Baron,” Ethics, vol. 59, no. 2 (January 1949), pp. 147-148.

- “Review of Book: The Web of Government, by Robert M. MacIver,“ American Journal of Sociology, vol. 54, no. 4 (January 1949), pp. 390-391.

- “The Primacy of the National Interest,” American Scholar, vol. 18, no. 2 (Spring 1949), pp. 207-212.

- “Review of Book: Constitutional Dictatorship, by Clinton L. Rossiter,“ American Journal of Sociology, vol. 54, no. 6 (May, 1949), pp. 566-567.

- “Review of Book: Strategic Intelligence for American World Policy, by Sherman Kent,” American Political Science Review, vol. 43, no. 5 (October 1949), pp. 1046-1047.

- Edited with Kenneth W. Thompson, Principles and Problems of International Politics: Selected Readings (New York: Knopf, 1950).

- “The Conduct of Foreign Policy,” in Sydney D. Bailey, ed., Aspects of American Government: A Symposium (London: Hansard Society, 1950).

- “Power Politics,” in Freda Kirchwey, ed., The Atomic Era: Can It Bring Peace and Abundance? (New York: Medill McBride, 1950).

- “The H Bomb and the Peace Outlook,” in Stewart Alsop, et al., The H Bomb (New York: Didier, 1950), pp. 160-174.

- “The Pathology of Power,” American Perspective, vol. 4, no. 1 (Winter 1950), pp. 6-10.

- b“The Conquest of the United States by Germany,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 6, no. 1 (January 1950), pp. 21-27 [IAF, pp. 152-167].

- “The Decline of Liberty and Mr. Laski,” Common Cause, vol. 3 (March 1950), pp. 440-444 [DP, pp. 343-349; RAP, pp. 29-35].

- “The H-Bomb and After,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 6, no. 3 (March 1950), pp. 76-79 [RAP, pp. 119-127].

- “Strategy of Error,” University of Chicago Magazine (March 1950), pp. 9-15.

- “Can Total Diplomacy Avert Total War? Power Politics,” The Nation (May 20, 1950), pp. 486-487.

- “On Negotiating with the Russians,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 6, no. 5 (May 1950), pp. 143-148.

- “The Evil of Power: A Critical Study of de Jouvenel’s On Power,” Review of Metaphysics, vol. 3, no. 4 (June 1950), pp. 507-517 [DP, pp. 358-367; RAP, pp. 44-53].

- “The Case for Negotiation: History’s Lesson,” The Nation (December 16, 1950), pp. 587-591.

- “The Mainsprings of American Foreign Policy: The National Interest vs. Moral Abstractions,” American Political Science Review, vol. 44, no. 4 (December 1950), pp. 833-854.

- In Defense of the National Interest: A Critical Examination of American Foreign Policy (New York: Knopf, 1951).

- “Germany: The Political Problem,” in Morgenthau, ed., Germany and the Future of Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951) [IAF, pp. 195-206].

- “The Moral Dilemma in Foreign Policy,” Year Book of World Affairs, vol. 5 (1951), pp. 12-36 [DP, pp. 246-255; DDP, pp. 318-327].

- “The Policy of the U. S. A.,” The Political Quarterly, vol. 22, no. 1 (January-March 1951), pp.43-56.

- “A Positive Approach to a Democratic Ideology,” Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science, vol. 24, no. 2 (January 1951), pp. 79-90 [RAP, pp. 237-247].

- “The Real Issue between United States and Russia,” University of Chicago Magazine (April 1951), pp. 5-8 and 25.

- “American Diplomacy: The Dangers of Righteousness,” The New Republic, vol. 125, issue 17 (October 22, 1951), pp. 117-119.

- “International Organization and Foreign Policy,” in Lyman Bryson, et al., eds., The Foundations of World Organization: A Political and Cultural Appraisal, Eleventh Symposium (New York: Harper. 1952) [IAF, pp. 107-111].

- “Building a European Federation,” Proceedings of the American Society of International Law at Its Annual Meeting, vol. 46 (1952), pp. 130-134 [RAP, pp. 231-236].

- “Klassische Zeit amerikanischer Staatskunst,” Aussenpolitik, Jg. 3, H. 1 (Januar 1952), S. 19-28.

- “Review of Book: Power and Society, by Harold D. Lasswell and Abraham Kaplan,” American Political Science Review, vol. 46, no. 1 (March 1952), pp. 230-234.

- “Marxism: From Political Philosophy to Political Religion,” Walgreen Lectures (University of Chicago, March-April 1952) MS in HJMP, Container No. 169.

- “What Is the National Interest of the United States?” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 282 (July 1952), pp. 1-7.

- “Area Studies and the Study of International Relations,” International Social Science Bulletin, vol. 4, no. 4 (Fall 1952), pp. 647-655 [DP, pp. 88-100; DDP, pp. 113-126:].

- “The Lessons of World War II’s Mistakes: Negotiations and Armed Power Flexibly Combined,” Commentary, vol. 10 (October 1952), pp. 326-333 [DP, pp. 256-269; DDP, pp. 328-341].

- “Another “Great Debate”: The National Interest of the United States,” American Political Science Review, vol. 46, no. 4 (December 1952), pp. 961-988 [DP, pp. 54-87; DDP, pp. 79-112].

- “Political Limitations of the United Nations,” in George A. Lipsky, ed., Law and Politics in the Contemporary World: Essays on Hans Kelsen’s Pure Theory and Related Problems in International Law (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1953) [IAF, pp. 112-118].

- “The Reconstruction of Our German Policy,” Economists (July 11, 1953) [IAF, pp. 207-208].

- “A Melancholy Fact: Review of The Challenge to American Foreign Policy, by John J. McCloy,” The New Republic, vol. 128, issue 30 (July 27, 1953), pp. 18-19.

- “The Unfinished Business of United States Foreign Policy,” Wisconsin Idea (Fall 1953) [IAF, pp. 8-15].

- “The Moral Standards of the Social Scientist,” Paper presented at the Seminar: Morals in Government, Conference on Moral Standards (September 13-15, 1953) MS in HJMP, Container No. 169.

- Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, 2nd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1954).

- “The New United Nations and the Revision of the Charter,” The Review of Politics, vol. 16, no. 1 (January 1954), pp. 3-21 [IAF, pp. 130-135].

- “Germany Will Decide Her Own Fate,” The New Republic, vol. 130, issue 5 (February 1, 1954), pp. 9-11 [IAF, pp. 209-215].

- “Review of Book: Governing Postwar Germany, by Edward H. Litchfield and Associates,” Harvard Law Review, vol. 67, no. 5 (March 1954), pp. 904-906.

- “Will It Deter Aggression?” The New Republic, vol. 130, issue 13 (March 29, 1954), pp. 11-14 [RAP, pp. 128-133].

- “The Theoretical and Practical Importance of a Theory of International Relations,’’ MS for the Conference on Theory of International Politics (May 7, 1954) in HJMP, Container No. 176.

- “US and UN,” Foreign Policy Bulletin, vol. 33 (September 15, 1954), pp. 5-6 [RAP, pp. 273-275].

- “The Political and Military Strategy of the United States,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 10, no. 10 (October 1954), pp. 323-327 [IAF, pp. 16-24].

- “The Yardstick of the National Interest,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 296 (November 1954), pp. 77-84 [IAF, pp. 119-129].

- “Germany’s New Role,” Commonweal (November 12, 1954) [IAF, pp. 216-227].

- “United States Foreign Policy,” Year Book of World Affairs, vol. 9 (1955), pp. 1-21 [DP, pp. 324-339; DDP, pp. 409-424].

- “The United States, India, and Asia,” Proceedings of the Twenty-First Institute of the Norman Wait Harris Memorial Foundation (University of Chicago, 1955) [IAF, pp. 283-288].

- “United States Policy toward Africa,” in Calvin W. Stillman, ed., Africa in the Modern World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955) [IAF, pp. 297-308].

- “Toward a Theory of International Politics,” (1955) MS in HJMP, Container No. 170.

- “Government Administration and Security,” Current History, vol. 29, no. 170 (1955), pp. 210-216. *

- “Foreign Policy: The Conservative School,” World Politics, vol. 7, no. 2 (January 1955), pp. 284-292.

- “The Formosa Resolution of 1955,” Chicago Sun-Times (January 30, 1955) [IAF, pp. 278-282].

- “The Revolution We Are Living Through,” The Intercollegian, vol. 72 (February 1955), pp. 8-10 [IAF, pp. 247-250].

- “Religion und Fanatismus,” Kontinente: Gedanken und Gespräche der Gegenwart, Jg. 8, H. 6 (Februar 1955), S. 27-28.

- “Reason and Restoration in the West,” The New Republic, vol. 132, issue 8 (February 21, 1955), pp. 12-28 [DP, pp. 377-381; RAP, pp. 63-67].

- “Toynbee and the Historical Imagination,” Encounter, vol. 4, no. 3 (March 1955), pp. 70-76 [DP, pp. 368-376; RAP, pp. 54-62].

- “The Impact of the Loyalty-Security Measures on the State Department,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 11, no. 4 (April 1955), pp. 134-140 [DP, pp. 305-323; DDP, pp. 390-408].

- “A State of Insecurity,” The New Republic, vol. 132, issue 16 (April 18, 1955), pp. 8-14 [DP, pp. 305-323; DDP, pp. 390-408].

- “Reflections on the State of Political Science,” The Review of Politics, vol. 17, no. 4 (October 1955), pp. 431-460 [DP, pp. 7-43; DDP, pp. 16-52].

- “The Art of Diplomatic Negotiation,” in Leonard D. White, ed., The State of the Social Sciences: Papers Presented at the 25th Anniversary of the Social Science Research Building, the University of Chicago, November 10-12, 1955 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956) [DP, pp. 270-280; RAP, pp. 198-208].

- “The 1954 Geneva Conference: An Assessment,” in A Symposium on America's Stake in Vietnam (New York: American Friends of Vietnam, 1956). *

- “Has Atomic War Really Become Impossible?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 12, no. 1 (January 1956), pp. 7-9 [RAP, pp. 134-141].

- “Principles of International Politics,” Naval War College Review, vol. 8, no. 6 (February 1956), pp. 1–13.

- “Background to Civil War,” Washington Post (February 26, 1956) [VUS, pp. 21-24].

- “The Immaturity of Our Asian Policy I: Ideological Windmills,” The New Republic, vol. 134, issue 11 (March 12, 1956), pp. 20-22 [IAF, pp. 251-257].

- “The Immaturity of Our Asian Policy II: Military Illusions,” The New Republic, vol. 134, issue 12 (March 19, 1956), pp. 14-16 [IAF, pp. 257-264].

- “The Immaturity of Our Asian Policy III: The Frustrations of Foreign Aid,” The New Republic, vol. 134, issue 13 (March 26, 1956), pp. 13-15 [IAF, pp. 264-270].

- “The Immaturity of Our Asian Policy IV: The Dangers of Doing Too Much,” The New Republic, vol. 134, issue 16 (April 16, 1956), pp. 14-16 [IAF, pp. 270-277].

- “Notes on a German Journey,” The New Republic, vol. 135, issue 9, (August 27, 1956), pp. 10-13 [IAF, pp. 228-235].

- “Diplomatic Calamities,” New York Times (November 13, 1956) [IAF, p. 25].

- “The Decline and Fall of American Foreign Policy,” The New Republic, vol. 135, issue 24 (December 10, 1956), pp. 11-16 [IAF, pp. 26-37].

- “The Decline and Fall of American Foreign Policy II: What the President and Mr. Dulles Don't Know” The New Republic, vol. 135, issue 25 (December 17, 1956), pp. 14-18 [DP, pp. 295-304; DDP, pp. 380-389].

- “Introduction,” in Ernest W. Lefever, Ethics and United States Foreign Policy (New York: Meridian Books, 1957).

- “Neutrality and Neutralism,” Year Book of World Affairs, vol. 11 (1957), pp. 47-75 [DP, pp. 185-209; DDP, pp. 257-281].

- “Les dangers du ‘néo-pazifisme’,” Preuves, no. 80 (1957), pp. 66-70. *

- “Pronouncements Are Not Policies: A Reply to Readers’ Comments on “American Foreign Policy”,” The New Republic, vol. 136, issue 1 (January 7, 1957), pp. 15-16.

- “Disarmament,” Statement before a Subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations (January 10, 1957) [RAP, pp. 142-154].

- “The New Pattern of World Politics,” The New Republic, vol. 136, issue 2 (January 14, 1957), pp. 17-18.

- “The Revolution in United States Foreign Policy: From Containment to Spheres of Influence?” Commentary (February 1957), pp. 101-105 [IAF, pp. 38-45].

- “Atomic Force and Foreign Policy: Can the “New Pacifism” Insure Peace?” Commentary (June 1957) [RAP 155-161].

- “The Paradoxes of Nationalism,” Yale Review, vol. 46, no. 4 (June 1957), pp. 481-496 [DP, pp. 170-184; DDP, pp. 181-195].

- “Wirkungsformen traditioneller und demokratisch kontrollierter Diplomatie,” Funk-Universität, RIAS, Berlin (June 11, 1957) MS in HJMP, Container No. 199.

- “Sources of Tension between Western Europe and the United States,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 312 (July 1957), pp. 22-28.

- “The Qualifications of an Ambassador,” Letters to New York Times (August 13, 1957) and Washington Post (August 6, 1957) [RAP, pp. 209-212].

- “The Dilemmas of Freedom,” American Political Science Review, vol. 51, no. 3 (September 1957), pp. 714-733 [DP, pp. 104-115; RAP, pp. 71-82].

- “Is the United Nations in Our National Interest?” Foreign Policy Bulletin (September 15, 1957) [RAP, pp. 276-278].

- “Der Pazifismus des Atomzeitalters,” Der Monat, 10 (Oktober 1957), S. 3-8.

- “The Fortieth Anniversary of the Bolshevist Revolution,” Chicago Sun-Times (November 3, 1957) [IAF, pp. 139-142].

- “The Decline of America I: The Decline of American Power,” The New Republic, vol. 137, issue 25 (December 9, 1957), pp. 10-14 [IAF, pp. 46-55].

- “The Decline of America II: The Decline of American Government,” The New Republic, vol. 137, issue 26 (December 16, 1957), pp. 7-11 [DP, pp. 281-291; RAP, pp. 90-100].

- Dilemmas of Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958).

- “The Crisis of the Atlantic Alliance,” Western World, no. 12 (1958), pp. 13-16. *

- “The New Despotism and the New Feudalism,” in Committee for Economic Development, ed., Problems of United States Economic Development, no. 1 (New York: Committee for Economic Development, 1958), pp. 281-286 [DP, pp. 116-122; RAP, pp. 83-89].

- “Power as a Political Concept,” in Roland Young, ed., Approaches to the Study of Politics (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1958).

- “Alliances,” Confluence: An International Forum, vol. 4, no. 6 (Winter 1958), pp. 311-334 [RAP, pp. 176-197].

- “Realism in International Politics,” Naval War College Review, vol. 10, no. 5 (January 1958), pp. 1-15.

- “A Reassessment of United States Foreign Policy,” Lecture given in the Great Issues Course at Dartmouth College, (February 10, 1958) [IAF, pp. 56-67].

- “Russian Technology and American Policy,” Current History, vol. 34, no. 199 (March 1958), pp. 129-135 [IAF, pp. 143-151].

- “Should We Negotiate Now? Hazards of a Summit Meeting,” Commentary (March 1958), pp. 192-199 [IAF, pp. 168-180].

- “The Lebanese Disaster,” The New Republic, vol. 139, issue 5/6 (August 4, 1958), pp. 14-17 [IAF, pp. 289-296].

- “Review of Book: Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy, by Henry A. Kissinger,” American Political Science Review, vol. 52, no. 3 (September 1958), pp. 842-844.

- “The New United Nations: What It Can’t and Can Do,” Commentary (November 1958), pp. 375-382.

- “The Last Years of Our Greatness? Khrushchev’s Message to the 86th Congress,” The New Republic, vol. 139, issue 26 (December 29, 1958), pp. 11-16 [PAP, pp. 324-341].

- “The Permanent Values in the Old Diplomacy,” in Stephen D. Kertesz and M. A. Fitzsimons eds., Diplomacy in a Changing World (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1959).

- “The Nature and Limits of a Theory of International Relations,” in William T. R. Fox, ed., Theoretical Aspects of International Politics (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1959).

- “Alliances in Theory and Practice,” in Arnold Wolfers, ed., Alliance Policy in the Cold War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1959). *

- “Introduction,” in D. A. Graber, Crisis Diplomacy: A History of U. S. Intervention Policies and Practices (Washington: Public Affairs Press, 1959) [IAF, pp. 5-7].

- “Soviet Policy and World Conquest,” Current History, vol. 37, no. 219 (1959), pp. 290-294. *

- “Contradictions in US China Policy,” in Urban Whitaker, ed., Foundations of US China Policy (Berkeley: Pacifica Foundation, 1959).

- “The Decline of Democratic Government,” University of Chicago Magazine, no. 1 (1959), pp. 5-8. *

- “Education and the World Scene,” Dædalus, vol. 88, no. 1 (Winter, 1959), pp. 121-138 [DDP, pp. 113-126].

- “The Economics of Foreign Policy,” Challenge: The Magazine of Economic Affairs, vol. 7, no. 5 (February 1959), pp. 8-13 [RAP, pp. 248-253].

- “Why Nations Decline,” Lecture given at the National War College (April 10, 1959) [DDP, pp. 201-211].

- “Separating the Issues,” The New Republic, vol. 140, issue 19 (May 11, 1959), pp. 13-14.

- “What Is Wrong with Our Foreign Policy,” Statement before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations (April 15, 1959) [IAF, pp. 68-94].

- “What the Big Two Can, and Can’t Negotiate,” New York Times Magazine (September 20, 1959) [RAP, pp. 315-322].

- “The Realist and Idealist Views of International Relations: A Realist’s Interpretation,” Lecture at the US-Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania (September 28, 1959) MS in HJMP, Container No. 170.

- “National Security Policy,” Lecture given at National War College (October 13, 1959) [IAF, pp. 95-104].

- “Khrushchev’s New Cold War Strategy: Prestige Diplomacy,” Commentary (November 1959), pp. 381-388 [IAF, pp. 181-192].

- “The Great Betrayal,” New York Times Magazine (November 22, 1959) [DDP, pp. 361-367; PAP, pp. 342-350].

- “Epistle to the Columbians,” The New Republic, vol. 141, issue 25 (December 21, 1959), pp. 8-10 [DDP, pp. 368-374; PAP, pp. 351-359].

- The Purpose of American Politics (New York: Knopf, 1960).

- Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, 3rd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1960).

- “Reflectiones sobre la politica exterior de la union sovietica,” Revista de ciencias socials de la Universidad de Puerto Rico (1960), pp. 437-445.

- The Crisis of American Foreign Policy: The Brian McMahon Lectures (Mansfield: University of Connecticut, 1960).

- “Introduction,” in Vladimir Reisky de Dubnic, Communist Propaganda Methods: A Case Study on Czechoslovakia (New York: Praeger, 1960).

- “Foreword,” in Robert O. Byrd, Quaker Ways in Foreign Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1960) [DDP, pp. 375-376: “Christian Ethics and Political Action”].

- “The World Situation,” Answers to Questions posed by Sekai (Tokyo: January, 1960) [RAP, pp. 295-299].

- “An Approach to the Summit,” The New Leader, vol. 43, issue 1 (January 4, 1960), pp. 10-13 [RAP, pp. 285-292].

- “The Intellectual and Moral Dilemma of Politics,” Christianity and Crisis (February 8, 1960) [DDP, pp. 7-15].

- “The Principles of Propaganda,” Democratic Advisory Council, Advisory Committee on Foreign Policy (May 31, 1960) [TAP, pp. 315-324].

- “Resuming Contact with the Russians,” The New Republic, vol. 142, issue 23 (June 6, 1960), p. 10.

- “The Social Crisis in America: Hedonism of Status Quo,” Chicago Review, vol. 14, no. 2 (Summer 1960), pp. 69-88.

- “The Demands of Prudence,” Worldview, vol. 3, no. 6 (June 1960), pp. 6-7 [RAP, pp. 15-18].

- “Our Thwarted Republic: Public Power vs. the New Feudalism,” Commentary 30 (June 1960), pp. 473-482.

- “The Problem of German Reunification,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 330, no. 1 (July 1960), pp. 130-134 [IAF, pp. 236-244].

- “America: Its Purpose and its Power,” Worldview, vol. 3, no. 11 (November 1960), pp. 4-7.

- “The President,” New York Times Magazine (November 13, 1960) [RAP, pp. 379-384].