Roscoe Arbuckle

Roscoe Arbuckle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 24, 1887 Smith Center, Kansas, United States |

| Died | June 29, 1933 (aged 46) New York City, New York, United States |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Fatty Arbuckle William Goodrich |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, comedian, director, screenwriter |

| Years active | 1904–1933 |

| Spouse(s) |

Doris Deane (m. 1925–1929) |

| Relatives | Maclyn Arbuckle(cousin) Andrew Arbuckle(cousin) |

| Website | Official website |

Roscoe Conkling "Fatty" Arbuckle (March 24, 1887 – June 29, 1933) was an American silent film actor, comedian, director, and screenwriter. Starting at the Selig Polyscope Company he eventually moved to Keystone Studios where he worked with Mabel Normand and Harold Lloyd. He mentored Charlie Chaplin and discovered Buster Keaton and Bob Hope.

Arbuckle was one of the most popular silent stars of the 1910s, and soon became one of the highest paid actors in Hollywood, signing a contract in 1921 with Paramount Pictures for US$1 million.[1]

In September 1921, Arbuckle attended a party at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco during the Labor Day weekend. Bit player Virginia Rappe became drunk and ill at the party; she died four days later at a sanitarium known for performing abortions. Arbuckle was accused by a well known madam of raping and accidentally killing Rappe. Arbuckle endured three widely publicized trials which lasted from November 1921 to April 1922 for rape and manslaughter. His films were subsequently banned and he was publicly ostracized.

After the first two trials, which resulted in hung juries, Arbuckle was acquitted in the third trial and received a formal written apology from the jury; however, the trials scandal has mostly overshadowed his legacy as a pioneering comedian.[1] Although the ban on his films was lifted within a year, Arbuckle only worked sparingly through the 1920s. He later worked as a film director under the alias 'William Goodrich'. He was finally able to return to acting, making short two-reel comedies in 1932 for Warner Brothers. He died in his sleep of a heart attack in 1933 at age 46, reportedly on the same day he signed a contract with Warner Brothers to make a feature film.[1]

Early life

Roscoe Arbuckle was born in Smith Center, Kansas, one of nine children of Mollie and William Goodrich Arbuckle. He weighed in excess of 13 lb (5.9 kg) at birth and, as both parents had slim builds, his father believed the child was not his. This disbelief led him to name the child after a politician (and notorious philanderer) whom he despised, Republican senator Roscoe Conkling of New York. The birth was traumatic for Mollie and resulted in chronic health problems that contributed to her death 12 years later.[2] When Arbuckle was nearly two his family moved to Santa Ana, California.[3]

Arbuckle had a "wonderful" singing voice and was extremely agile. At the age of eight, with his mother's encouragement, he first performed on stage with Frank Bacon's company during their stopover in Santa Ana.[3] Arbuckle enjoyed performing and continued on until his mother's death in 1899 when he was 12. His father, who had always treated him harshly,[4] now refused to support him and Arbuckle got work doing odd jobs in a hotel. Arbuckle was in the habit of singing while he worked and was overheard by a customer who was a professional singer. The customer invited him to perform in an amateur talent show. The show consisted of the audience judging acts by clapping or jeering with bad acts pulled off the stage by a shepherd's crook. Arbuckle sang, danced, and did some clowning around but did not impress the audience. He saw the crook emerge from the wings and to avoid it somersaulted into the orchestra pit in obvious panic. The audience went wild, and he not only won the competition but began a career in vaudeville.[2]

Career

In 1904 Arbuckle was invited by Sid Grauman to sing in his new Unique Theater in San Francisco, which was the start of a long friendship between the two.[5][6] He then joined the Pantages Theatre Group touring the West Coast of the United States and in 1906 played the Orpheum Theater in Portland, Oregon in a vaudeville troupe organized by Leon Errol. Arbuckle became the main act and the group took their show on tour.[7]

On August 6, 1908, Arbuckle married Minta Durfee (1889–1975), the daughter of Charles Warren Durfee and Flora Adkins. Durfee starred in many early comedy films, often with Arbuckle.[8][9] They reportedly made a strange couple as Minta was short and petite while Arbuckle was tall and very large.[2] Arbuckle then joined the Morosco Burbank Stock vaudeville company and went on a tour of China and Japan returning in early 1909.[citation needed]

Arbuckle began his film career with the Selig Polyscope Company in July 1909 when he appeared in Ben's Kid. Arbuckle appeared sporadically in Selig one-reelers until 1913, moved briefly to Universal Pictures and became a star in producer-director Mack Sennett's Keystone Cops comedies. (However, according to the Motion Picture Studio Directory for 1919 and 1921, Arbuckle began his screen career with Keystone in 1913 as an extra for $3 a day, working his way up through the acting ranks to become a lead player and director.) Although his large size was undoubtedly part of his comedic appeal Arbuckle was self-conscious about his weight and refused to use it to get "cheap" laughs. For example he would not allow himself to be stuck in a doorway or chair.[citation needed]

Arbuckle was a talented singer. After Enrico Caruso heard him sing he urged the comedian to: "...give up this nonsense you do for a living, with training you could become the second greatest singer in the world."[10]

Screen comedian

Despite his massive physical size, Arbuckle was remarkably agile and acrobatic. Director Mack Sennett, when recounting his first meeting with Arbuckle, noted that he "skipped up the stairs as lightly as Fred Astaire"; and, "without warning went into a feather light step, clapped his hands and did a backward somersault as graceful as a girl tumbler". His comedies are noted as rollicking and fast-paced, have many chase scenes, and feature sight gags. Arbuckle was fond of the famous "pie in the face", a comedy cliché that has come to symbolize silent-film-era comedy itself. The earliest known use of this gag was in the June 1913 Keystone one-reeler A Noise from the Deep, starring Arbuckle and frequent screen partner Mabel Normand. The first known "pie in the face" on-screen is in Ben Turpin's Mr. Flip in 1909. However, the oldest known thrown "pie in the face" is Normand's.[citation needed]

In 1914, Paramount Pictures made the then-unheard of offer of US$1,000-a-day plus 25% of all profits and complete artistic control to make movies with Arbuckle and Normand. The movies were so lucrative and popular that in 1918 they offered Arbuckle a three-year, $3 million contract (equivalent to about $43 million in 2010).[11][12]

By 1916, Arbuckle's weight and heavy drinking were causing serious health problems. An infection that developed on his leg became a carbuncle so severe that amputation was considered. Although Arbuckle kept his leg and lost 80 lb (36 kg), managing to get his weight down to 266 lbs (120 kg), he became addicted to the pain killer morphine.[2]

Following his recovery, Arbuckle started his own film company, Comique, in partnership with Joseph Schenck. Although Comique produced some of the best short pictures of the silent era, in 1918 Arbuckle transferred his controlling interest in the company to Buster Keaton and accepted Paramount's $3 million offer to make up to 18 feature films over three years.[2]

Arbuckle disliked his screen nickname, which he had been given because of his substantial girth. "Fatty" had also been Arbuckle's nickname since school; "It was inevitable", he said. He weighed 185 lb (84 kg) when he was 12. Fans also called Roscoe "The Prince of Whales" and "The Balloonatic." However, the name Fatty identifies the character that Arbuckle portrayed on-screen (usually, a naive hayseed)—not Arbuckle himself. When Arbuckle portrayed a female, the character was named "Miss Fatty", as in the film Miss Fatty's Seaside Lovers. Arbuckle discouraged anyone from addressing him as "Fatty" off-screen, and when they did so his usual response was, "I've got a name, you know."[13]

The scandal

On September 5, 1921, Arbuckle took a break from his hectic film schedule and, despite suffering from second degree burns to both buttocks from an accident on set, drove to San Francisco with two friends, Lowell Sherman (an actor/director) and cameraman Fred Fischbach. The three checked into three rooms: 1219 (Arbuckle and Fischbach), 1220 (empty), and 1221 (Sherman) at the St. Francis Hotel. They had rented 1220 as a party room and invited several women to the suite.[1]

During the carousing, a 30-year-old aspiring actress named Virginia Rappe was found seriously ill in room 1219 and was examined by the hotel doctor, who concluded her symptoms were mostly caused by intoxication and gave her morphine to calm her. Rappe was not hospitalized until two days after the incident.[1]

Virginia Rappe suffered from chronic cystitis,[15] a condition that flared up dramatically whenever she drank. Her heavy drinking habits and the poor quality of the era's bootleg alcohol could leave her in severe physical distress. She developed a reputation for over-imbibing at parties, then drunkenly tearing at her clothes from the resulting physical pain. But by the time of the St. Francis Hotel party, her reproductive health was a greater concern. She had undergone several abortions in the space of a few years, the quality of care she received for such procedures was probably substandard, and she was preparing to undergo another (or, more likely, had recently done so) as a result of being impregnated by her boyfriend, director Henry Lehrman.[16][17]

At the hospital, Rappe's companion at the party, Bambina Maude Delmont, told Rappe's doctor that Arbuckle had raped her friend. The doctor examined Rappe but found no evidence of rape. Rappe died one day after her hospitalization of peritonitis, caused by a ruptured bladder. Delmont then told police that Arbuckle raped Rappe, and the police concluded that the impact Arbuckle's overweight body had on Rappe eventually caused her bladder to rupture.[1] Rappe's manager Al Semnacker (at a later press conference) accused Arbuckle of using a piece of ice to simulate sex with her, which led to the injuries.[18] By the time the story was reported in newspapers, the object had evolved into being a Coca-Cola or champagne bottle, instead of a piece of ice. In fact, witnesses testified that Arbuckle rubbed the ice on Rappe's stomach to ease her abdominal pain. Arbuckle denied any wrongdoing. Delmont later made a statement incriminating Arbuckle to the police in an attempt to extort money from Arbuckle's attorneys.[19]

Arbuckle's trial was a major media event; exaggerated and sensationalized stories were run in William Randolph Hearst's nationwide newspaper chain. The story was fueled by yellow journalism, with the newspapers portraying him as a gross lecher who used his weight to overpower innocent girls. In reality, Arbuckle was a good-natured man who was so shy with women that he was regarded by those who knew him as, "the most chaste man in pictures".[2] Hearst was gratified by the Arbuckle scandal, and later said that it had "sold more newspapers than any event since the sinking of the RMS Lusitania."[20] The resulting scandal destroyed Arbuckle's career and his personal life. Morality groups called for Arbuckle to be sentenced to death, and studio executives ordered Arbuckle's industry friends and fellow actors (whose careers they controlled) not to publicly speak up for him. Charles Chaplin was in England at the time and therefore was never available for comment on the Arbuckle case. Buster Keaton did make a public statement in support of Arbuckle's innocence. Film actor William S. Hart, who had never met or worked with Arbuckle, made a number of public statements which he presumed that Arbuckle was guilty.[citation needed]

The prosecutor, San Francisco District Attorney Matthew Brady, an intensely ambitious man who planned to run for governor, made public pronouncements of Arbuckle’s guilt and pressured witnesses to make false statements.[1] Brady at first used Delmont as his star witness during the indictment hearing.[1] Although the judge threatened Brady with dismissal of the case, Brady refused to allow Delmont, the only witness accusing Arbuckle, to take the stand and testify. Delmont had a long criminal record with convictions for racketeering, bigamy, fraud, and extortion, and allegedly was making a living by luring men into compromising positions and capturing them in photographs, to be used as evidence in divorce proceedings.[21] The defense had also obtained a letter from Delmont admitting to a plan to extort payment from Arbuckle. In view of Delmont’s constantly changing story,[1] her testimony would have ended any chance of going to trial. Ultimately, the judge found no evidence of rape. After hearing testimony from one of the party guests, Zey Prevon, that Rappe told her "Roscoe hurt me" on her deathbed, the judge decided that Arbuckle could be charged with first-degree murder. Brady had originally planned to seek the death penalty. The charge was later reduced to manslaughter.[1]

The first trial

Arbuckle was then arrested on the charges of manslaughter, but arranged bail after nearly three weeks in jail. The first trial began on November 14, 1921 in the city courthouse in downtown San Francisco.[1] Arbuckle's defence lawyer was Mr Dominquez. The principal witness was Ms Zay Prevost, a guest at the party.[22] At the beginning of the trial Arbuckle told his already-estranged wife, Minta Durfee, that he did not harm Rappe; she believed him and appeared regularly in the courtroom to support him. Public feeling was so negative that she was later shot at while entering the courthouse.[20]

Brady's first witnesses during the trial included Betty Campbell, a model, who attended the September 5 party and testified that she saw Arbuckle with a smile on his face hours after the alleged rape occurred; Grace Hultson, a local nurse who testified it was very likely that Arbuckle did rape Rappe and bruise her body in the process; and Dr. Edward Heinrich, a local criminologist who claimed he found Arbuckle's fingerprints smeared with Rappe's blood on room 1219's bathroom door. Dr. Arthur Beardslee, the hotel doctor, testified that an external force seemed to have damaged the bladder. During cross-examination, Betty Campbell, however, revealed that Brady threatened to charge her with perjury if she did not testify against Arbuckle.[1] Dr. Heinrich's claim to have found fingerprints was cast into doubt after Arbuckle's defense attorney, Gavin McNab, produced the St. Francis hotel maid, who testified that she had cleaned the room before the investigation even took place and did not find any blood on the bathroom door. Dr. Beardslee admitted that Rappe had never mentioned being assaulted while he was treating her. McNab was furthermore able to get Nurse Hultson to admit that the rupture of Rappe's bladder could very well have been a result of cancer, and that the bruises on her body could also have been a result of the heavy jewelry she was wearing that evening.[1] During the defense stage of the trial, McNab called various pathology experts who testified that while Rappe's bladder had ruptured, there was evidence of chronic inflammation and no evidence of any pathological changes preceding the rupture; in other words, there was no external cause for the rupture.[citation needed]

Taking the witness stand as the defense's final witness, Arbuckle was simple, direct, and unflustered in both direct and cross examination. In his testimony, Arbuckle claimed that Rappe (whom he testified that he had known for five or six years) came into the party room around midnight, and that some time afterward Mae Taub (daughter-in-law of Billy Sunday) asked him for a ride into town, so he went to his room (1219) to change his clothes and discovered Rappe vomiting in the toilet. Arbuckle then claimed Rappe told him she felt ill and asked to lie down, and that he carried her into the bedroom and asked a few of the party guests to help treat her. To calm Rappe down, they placed her in a bathtub of cool water. Arbuckle and Fischbach then took her to room 1227 and called the hotel manager and doctor. After the doctor declared Rappe was just drunk, Arbuckle then drove Taub to town.

During the whole trial, the prosecution presented medical descriptions of Rappe's bladder as evidence that she had an illness. In his testimony, Arbuckle denied he had any knowledge of Rappe's illness. During cross-examination, Brady aggressively grilled Arbuckle that he refused to call a doctor when he found Rappe sick, and argued that he refused to do so because he knew of Rappe's illness and saw a perfect opportunity to rape and kill her. Despite the frequent and aggressive badgering Brady inflicted upon Arbuckle during cross-examination, Arbuckle calmly maintained that he never physically hurt or sexually assaulted Rappe in any way during the September 5 party, and he also maintained that he never made any inappropriate sexual advances against any woman in his life. After over two weeks of testimony with 60 prosecution and defense witnesses, including 18 doctors who testified about Rappe's illness, the defense rested. On December 4, 1921, the jury returned deadlocked after 44 straight hours of deliberation with a 10–2 not guilty verdict, and a mistrial was declared.[1]

Arbuckle's attorneys later focused on one holdout named Helen Hubbard who had told jurors that she would vote guilty "until hell freezes over" and that she refused to look at the exhibits or read the trial transcripts, having made up her mind in the courtroom. Hubbard's husband was a lawyer who did business with the D.A.'s office,[23] and expressed surprise that she was not challenged when selected for the jury pool. While most of the focus was laid solely on Hubbard after the trial, a portion of the jurors felt Arbuckle guilty but not beyond a reasonable doubt, and various jurors joined Hubbard in voting to convict, including - repeatedly at the end - Thomas Kilkenny. Arbuckle researcher Joan Myers describes the political climate and media focus concerning women on juries (which had only been legal for four years at the time), and how Arbuckle's defense immediately focused on singling out Hubbard as a villain, while Hubbard described attempts to bully her into changing her vote by the jury foreman, August Fritze. While Hubbard offered explanations on her vote whenever challenged, Kilkenny remained mum and quickly faded from the media spotlight after the trial ended.[24]

The second trial

The second trial began on January 11, 1922 with a different jury, but with the same legal defense and prosecution as well as the same presiding judge. The same evidence was presented, but this time one of the witnesses, Zey Prevon, testified that Brady had forced her to lie.[25] Another witness who claimed that Arbuckle had bribed him not to tell anyone about harming Rappe turned out to be an ex-convict who was currently charged with sexually assaulting an eight-year-old girl, and who was looking for a sentence reduction from Brady in exchange for his testimony. Further, in contrast to the first trial, Rappe's history of promiscuity and heavy drinking was detailed. The second trial also discredited some major evidence such as the identification of Arbuckle's fingerprints on the hotel bedroom door: Heinrich took back his earlier testimony from the first trial and testified that the fingerprint evidence was likely faked.[25] The defense was so convinced of an acquittal that Arbuckle was not called to testify. Arbuckle's lawyer, McNab, made no closing argument to the jury. However, some jurors interpreted the refusal to let Arbuckle testify as a sign of guilt.[25] After over 40 hours of deliberation, the jury returned on February 3, deadlocked with a 9–3 guilty verdict. Another mistrial was declared.[25]

The third trial

By the time of the third trial, Arbuckle's films had been banned, and newspapers had been filled for the past seven months with stories of alleged Hollywood orgies, murder, and sexual perversion. Delmont was touring the country giving one-woman shows as "The woman who signed the murder charge against Arbuckle", and lecturing on the evils of Hollywood.

The third trial began on March 13, 1922, and this time the defense took no chances. McNab took an aggressive defense, completely tearing apart the prosecution's case. This time, Arbuckle again testified and maintained his denials in his heartfelt testimony about his version of the events at the hotel party. McNab also managed to get in still more evidence about Virginia Rappe's lurid past, and reviewed how Brady fell for the outlandish charges of Delmont, whom McNab described in his long closing statement as "the complaining witness who never witnessed". Another hole in the prosecution's case was opened because Zey Prevon, a key witness, was out of the country and unable to testify.[1] On April 12, the jury began deliberations and it took only six minutes to return a unanimous not guilty verdict—five of those minutes were spent writing a statement of apology, a dramatic move in American justice. The jury statement as read by the jury foreman stated:

Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle. We feel that a great injustice has been done to him... there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a crime. He was manly throughout the case and told a straightforward story which we all believe. We wish him success and hope that the American people will take the judgement of fourteen men and women that Roscoe Arbuckle is entirely innocent and free from all blame.

Some experts later concluded that Rappe's bladder might also have ruptured as a result of an abortion she might have had a short time before the September 5, 1921 party. Rappe's organs had been destroyed and it was now impossible to test for pregnancy.[1] Because alcohol was consumed at the party, Arbuckle was forced to plead guilty to one count of violating the Volstead Act, and had to pay a $500 fine[26] At the time of his acquittal, Arbuckle owed over $700,000 (around $9,444,583 adjusted for inflation in 2012) in legal fees to his attorneys for the three criminal trials,[26] and he was forced to sell his house and all of his cars to pay off some of the debt.[26]

Although he had been cleared of all criminal charges, the scandal and trials had greatly damaged his popularity among the general public, and Will H. Hays, who served as the head of the newly formed Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) Hollywood censor board, cited Arbuckle as an example of the poor morals in Hollywood.[26] On April 18, 1922, six days after Arbuckle's acquittal, Hays banned Roscoe Arbuckle from ever working in U.S. movies again.[26] He had also requested that all showings and bookings of Arbuckle films be canceled, and exhibitors complied. In December of the same year, Hays elected to lift the ban,[26] but Arbuckle was still unable to secure work as an actor.[26] Most exhibitors still declined to show Arbuckle's films, several of which now have no copies known to have survived intact. One of Arbuckle's feature-length films known to survive is Leap Year, which Paramount declined to release in the United States due to the scandal. It was eventually released in Europe.[citation needed]

Similar concurrent scandals

Although it was regarded as Hollywood's first major scandal,[1] the Arbuckle case was one of five major Paramount-related scandals of the period. In 1920, silent film actress Olive Thomas died after drinking a large quantity of mercury bichloride meant to topically treat her husband's (matinee idol Jack Pickford) syphilis.[27] In February 1922, the murder of director William Desmond Taylor effectively ended the careers of actresses Mary Miles Minter and former Arbuckle screen partner Mabel Normand. In 1923, actor/director Wallace Reid's drug addiction resulted in his death.[28] In 1924, actor/writer/director Thomas H. Ince died mysteriously, aboard William Randolph Hearst's yacht.[29]

Aftermath

The principal effect of the trial was an immediate shunning by Hollywood and a cessation of all acting roles. A secondary effect, sadly for archive history, was the purposeful destruction of copies of films starring Arbuckle.[30] In November 1923, Minta Durfee filed for divorce, charging grounds of desertion.[31] In January 1924, the divorce was granted.[32] They had been separated since 1921, though Durfee always claimed he was the nicest man in the world and that they were still friends.[33] After a brief reconciliation, Durfee again filed for divorce, this time from Paris, in December 1924.[34] Arbuckle married Doris Deane on May 16, 1925.[citation needed]

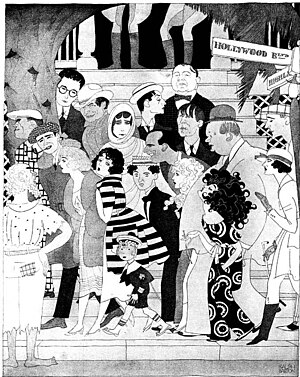

Arbuckle tried returning to filmmaking, but industry resistance to distributing his pictures continued to linger after his acquittal. He retreated into alcoholism. In the words of his first wife, "Roscoe only seemed to find solace and comfort in a bottle". Buster Keaton attempted to help Arbuckle by giving him work on his films. Arbuckle wrote the story for a Keaton short called Daydreams (1922). Arbuckle allegedly co-directed scenes in Keaton's Sherlock, Jr. (1924), but it is unclear how much of this footage remained in the film's final cut. In 1925, Carter Dehaven made the short Character Studies. Arbuckle appeared alongside Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Rudolph Valentino, Douglas Fairbanks, and Jackie Coogan.[35]

William Goodrich pseudonym

Eventually, Arbuckle was given work as a film director under the alias William Goodrich. According to author David Yallop in The Day the Laughter Stopped (a biography of Arbuckle with special attention to the scandal and its aftermath), Arbuckle's father's full name was William Goodrich Arbuckle. A persistent but unsupported legend credited Keaton, an inveterate punster, with suggesting that Arbuckle become a director under the alias "Will B. Good". The pun being too obvious, Arbuckle adopted the more formal pseudonym "William Goodrich".[citation needed]

During the middle and late 1920s and early 1930s, Arbuckle directed a number of comedy shorts under the pseudonym for Educational Pictures, which featured lesser-known comics of the day. Louise Brooks, who played the ingenue in Windy Riley Goes Hollywood (1931), told Kevin Brownlow:

He made no attempt to direct this picture. He sat in his chair like a man dead. He had been very nice and sweetly dead ever since the scandal that ruined his career. But it was such an amazing thing for me to come in to make this broken-down picture, and to find my director was the great Roscoe Arbuckle. Oh, I thought he was magnificent in films. He was a wonderful dancer—a wonderful ballroom dancer, in his heyday. It was like floating in the arms of a huge doughnut—really delightful.[20]

Second divorce

In 1929, Doris Deane sued for divorce in Los Angeles, charging desertion and cruelty.[36] On June 21, 1931, Roscoe married Addie Oakley Dukes McPhail (later Addie Oakley Sheldon, 1905–2003) in Erie, Pennsylvania.[citation needed]

Brief comeback and death

In 1932, Arbuckle signed a contract with Warner Bros. to star under his own name in a series of two-reel comedies, to be filmed at the Vitaphone studios in Brooklyn. These six shorts constitute the only recordings of his voice. Silent-film comedian Al St. John (Arbuckle's nephew) and actors Lionel Stander and Shemp Howard appeared with Arbuckle. The films were very successful in America, although when Warner Bros. attempted to release the first one (Hey, Pop!) in the United Kingdom, the British Board of Film Censors cited the 10-year-old scandal and refused to grant an exhibition certificate.[citation needed]

Arbuckle had finished filming the last of the two-reelers on June 28, 1933. The next day he was signed by Warner Bros. to make a feature-length film.[37] He reportedly said: "This is the best day of my life." He suffered a heart attack later that night and died in his sleep.[7] He was 46. His body was cremated and his ashes scattered in the Pacific Ocean.[citation needed]

Legacy

Many of Arbuckle's films, including the feature Life of the Party (1920), survive only as worn prints with foreign-language inter-titles. Little or no effort was made to preserve original negatives and prints during Hollywood's first two decades. By the early 21st century, some of Arbuckle's short subjects (particularly those co-starring Chaplin or Keaton) had been restored, released on DVD, and even screened theatrically. Arbuckle's early influence on American slapstick comedy is widely cited.[citation needed]

For his contribution to the film industry, Roscoe Arbuckle has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame located at 6701 Hollywood Blvd.[38]

In popular culture

Films

The James Ivory film The Wild Party (1975) has been repeatedly but incorrectly cited as a film dramatization of the Arbuckle/Rappe scandal. In fact it is loosely based on the 1926 poem by Joseph Moncure March.[39] In this film, James Coco portrays a heavy-set silent-film comedian named Jolly Grimm whose career is on the skids, but who is desperately planning a comeback. Raquel Welch portrays his mistress, who ultimately goads him into shooting her. This film may have been inspired by misconceptions surrounding the Arbuckle scandal, yet it bears almost no resemblance to the documented facts of the case.[citation needed]

Before his death in 1997, comedian Chris Farley expressed interest in starring as Arbuckle in a biography film. According to the 2008 biography The Chris Farley Show: A Biography in Three Acts, Farley and screenwriter David Mamet agreed to work together on what would have been Farley's first dramatic role.[40] In 2007 director Kevin Connor planned a film, The Life of the Party, based on Arbuckle's life. It was to star Chris Kattan and Preston Lacy. However the project was unable to find funding and was shelved in late 2008.[citation needed]

In April and May 2006, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City mounted a 56-film, month-long retrospective of all of Arbuckle's known surviving work, running the entire series twice. Highlights included The Rounders (1914) with Charlie Chaplin and Mabel and Fatty's Simple Life (1915) with Mabel Normand.[citation needed]

Books and music

Arbuckle is the subject of a 2004 novel entitled I, Fatty by author Jerry Stahl. The Day the Laughter Stopped by David Yallop and Frame-Up! The Untold Story of Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle by Andy Edmonds are other books on Arbuckle's life.[citation needed]

Fatty Arbuckle's is an American-themed restaurant chain in the UK prominent during the 1980s and named after Arbuckle.[citation needed]

The punk band NOFX has a song about Roscoe Arbuckle titled "I, Fatty" on their 2012 LP Self Entitled.[citation needed]

Arbuckle is mentioned on the Gwar's album America Must Be Destroyed in the song "Have You Seen Me?"[41]

Fictional portrayals

Arbuckle is played by actor Brett Ashy in the motion picture Return to Babylon (2013).

Filmography

- The Gangsters. 1913. Approx. 10 min.

- Fatty Joins the Force. 1913. Approx. 14:30 min.

- Fatty's New Role. 1915. Approx. 10 min.

- The Waiters' Ball. 1916. With Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- A Noise from the Deep. 1913. With Mabel Normand. Approx. 10 min.

- Mabel's New Hero. 1913. With Mabel Normand. Approx. 10 min.

- His Sister's Kids. 1913. With Minta Durfee. Approx. 10 min.

- A Flirt's Mistake. 1914. With Edgar Kennedy. Approx.10 min.

- Mabel's Blunder. 1914. With Mabel Normand. Approx 13:30 min.

- A Bath House Beauty. 1914. With Minta Durfee. Approx. 10 min.

- Those Country Kids. 1914. With Mabel Normand. Approx. 10 min.

- The Rounders. 1914. With Charlie Chaplin. Approx. 10 min.

- Tango Tangles. 1914. With Charlie Chaplin. Approx. 12 min.

- Lover's Luck. 1914. With Minta Durfee. Approx. 10 min.

- Fatty's Jonah Day. 1914. With Norma Nichols. Approx. 10 min.

- Mabel and Fatty's Simple Life (Fatty and Mabel's Simple Life). 1915. With Mabel Normand. Approx. 20 min.

- Mabel, Fatty and the Law. 1915. (Fatty's Spooning Days). Approx. 11 min.

- Wished on Mabel. 1915. With Mabel Normand. Approx. 10 min.

- Mabel and Fatty's Married Life (Fatty and Mabel's Married Life). 1915. With Mabel Normand. Approx. 10 min.

- Miss Fatty's Seaside Lovers. 1915. With Harold Lloyd. Approx. 10 min.

- Fatty's Tintype Tangle. 1915. With Louise Fazenda, Edgar Kennedy. Approx. 20 min.

- Fatty's Reckless Fling. 1915. Approx. 10 min.

- Fatty's Plucky Pup. 1915. 6:35 min.

- Fatty's Faithful Fido. 1915. With Luke the dog. Approx. 10 min.

- That Little Band of Gold. 1915. With Mabel Normand, Ford Sterling. Approx. 20 min.

- He Did and He Didn't. 1916. With Mabel Normand. Approx. 20 min.

- Fatty and Mabel Adrift. 1916. With Mabel Normand. Approx. 30 min.

- His Wife's Mistake. 1916. With Minta Durfee. Approx. 20 min.

- A Reckless Romeo. 1917. With Al St. John. Approx. 20 min

- A Creampuff Romance. 1917. Approx. 22 min.

- The Butcher Boy. 1917. With Buster Keaton (film debut) and Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- The Rough House. 1917. With Buster Keaton. Approx. 20 min.

- His Wedding Night. 1917. With Buster Keaton, Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- Coney Island. 1917. With Buster Keaton, Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- Out West. 1918. With Buster Keaton, Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- Moonshine. 1918. With Buster Keaton, Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- A Scrap of Paper. 1918. With Al St. John. Approx. 5 min.

- Good Night, Nurse. 1918. With Buster Keaton, Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- The Cook. 1918. With Buster Keaton, Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- The Hayseed. 1919. With Buster Keaton, Jack Coogan, Sr. Approx. 20 min.

- Back Stage. 1919. With Buster Keaton, Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- The Round-Up. 1920. With Tom Forman, Jean Acker, Wallace Beery. Approx. 70 min.

- Camping Out. 1919. With Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- Love. 1919. With Al St. John. Approx. 20 min.

- The Life of the Party. 1920. With Viora Daniel, Roscoe Karns. Approx. 50 min.

- The Garage. 1920. With Buster Keaton. Approx 20 min.

- Leap Year. 1921. Directed by James Cruze, with Lucien Littlefield and Mary Thurman. Approx 56 min.

Director

- Special Delivery. 1922. With Al St. John, Vernon Dent. Approx. 20 min.

- No Loafing. 1923. With Poodles Hanneford, Joe Roberts. (a surviving fragment of a two-reel short) Approx. 8 min.

- Stupid But Brave. 1924. With Al St. John, George Davis. Approx. 20 min.

- The Movies. 1925. With Lloyd Hamilton. Approx. 20 min.

- Curses!. 1925. With Al St. John, Bartine Burkett. Approx. 20 min.

- The Iron Mule. 1925. With Al St. John, Glen Cavender. Approx. 20 min.

- Dynamite Doggie. 1925. With Al St. John, Pete the Pup. Approx. 20 min.

- His Private Life. 1926. With Lupino Lane, George Davis. Approx. 20 min.

- Home Cured. 1926. With Johnny Arthur, Virginia Vance. Approx. 20 min.

- Fool's Luck. 1926. With Lupino Lane, George Davis. Approx. 20 min.

- My Stars. 1926. With Johnny Arthur, Virginia Vance, Florence Lee. Approx. 20 min.

- Special Delivery. 1927. With Eddie Cantor, Jobyna Ralston, William Powell. Approx. 60 min.

- Bridge Wives. 1932. With Al St. John, Fern Emmett. Approx. 10 min.

Vitaphone shorts

- Hey, Pop! 1932. With Billy Hayes. Approx. 20 min.

- Close Relations. 1933. With Charles Judels, Harry Shannon, and Shemp Howard. Approx. 20 min.

- Buzzin' Around. 1933. With Al St. John and Pete the Pup. Approx. 20 min.

- How've You Bean? 1933. With Fritz Hubert. Approx. 20 min.

- In the Dough. 1933. With Lionel Stander, Shemp Howard. Approx. 20 min.

- Tomalio. 1933. With Charles Judels. Approx. 20 min.

See also

- I, Fatty, a fictional account of the actor's life and career written by Jerry Stahl

- List of United States comedy films

- Rothwell-Smith, Paul. Silent Films! the Performers (2011) ISBN 9781907540325

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Noe, Denise. "Fatty Arbuckle and the Death of Virginia Rappe". Crime Library at truTV. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ a b c d e f Ellis, Chris & Julie (2005). Celebrity Murder: Murder played out in the spotlight of maximum publicity. Constable & Robertson. ISBN 1-84529-154-9.

- ^ a b Lowrey, Carolyn - The First One Hundred Noted Men and Women of the Screen, 1920, p. 6 Retrieved September 5, 2013

- ^ "Roscoe Always Jolly But Weak: Stepmother". The Evening News. 12 September 1921. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ Saperstein, Susan. "Grauman's Theaters". San Jose, California Guides. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ "She Must Use 7 Mirrors". The Evening News. 31 January 1905. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Dies in His Sleep. Film Comedian, Central Figure in Coast Tragedy in 1921, Long Barred From Screen. On Eve of his Comeback. Succumbs at 46 After He and Wife Had Celebrated Their First Wedding Anniversary". The New York Times. 1933-06-30. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

Roscoe C. (Fatty) Arbuckle, film comedian, died of a heart attack at 3 o'clock ... Roscoe Conkling Arbuckle was born at Smith Centre, Kansas, on March 24, 1887.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Minta Durfee, Actress, 85, Dies; Former Wife of Fatty Arbuckle". The New York Times. 1975-09-12. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

Minta Durfee, the actress who was married to Roscoe (Fatty) Arbuckle and became Charlie Chaplin's first motionpicture leading lady, died Tuesday in Woodland Hills, a Los Angeles suburb.

- ^ Del Olmo, Frank (1975-09-12). "Fatty Arbuckle's First Wife Dies". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ HOME VIDEO; Arbuckle Shorts, Fresh and Frisky The New York Times April 13, 2001

- ^ "Fatty Arbuckle Scandal". About.com. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ Equivalent to US$42.5 million per year in 2008 dollars

- ^ Alice Lake called him Arbie. To Mabel Normand he was Big Otto, after an elephant in the Selig Studio Zoo near Keystone. Buster Keaton called him Chief. Fred Mace called him Crab. And for some unexplained reason fellow comic Charlie Murray referred to him as My Child the Fat. His three wives always called him Roscoe.[1]

- ^ "When the Five O'Clock Whistle Blows in Hollywood". Vanity Fair. September 1922. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Testify Regarding Early Life Of Virginia Rappe". The Lewiston Daily Sun. 31 October 1921. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "Fatty Arbuckle and the Death of Virginia Rappe". trutv.com.

- ^ "Virginia Blamed Lover, Says Nurse". Ludington Daily News. 14 September 1921. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ Hopkins, Ernest J. (25 September 1921). "Miss Rappe's Manager Tells Worst He Knows Of Arbuckle". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^ francesfarmersrevenge.com

- ^ a b c "Fatty". Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ^ antimisandry.com

- ^ Daily Mirror headlines, October 1st 1921

- ^ Difficult Reputations: Collective Memories of the Evil, Inept, and Controversial; 2001; page 151. 1994, University of Chicago Press

- ^ [2]

- ^ a b c d "Fatty Arbuckle and the Death of Virginia Rappe - Crime Library on truTV.com". Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Fatty Arbuckle and the Death of Virginia Rappe - Crime Library on truTV.com". Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ Whitfield, Eileen (2007). Pickford: The Woman Who Made Hollywood. University Press of Kentucky. p. 224. ISBN 0-813-19179-3.

- ^ Braudy, Leo (2011). The Hollywood Sign: Fantasy and Reality of an American Icon. Yale University Press. p. 1924. ISBN 0-300-15878-5.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (August 18, 2007). "Give Louella An Ince; She'll Take A Column". snopes.com. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ Century of Scandal, ISBN 978-1-844259-50-2

- ^ "Milestones 11-12-23". Time. November 12, 1923. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ "Milestones 01-07-24". Time. January 7, 1924. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ "Excerpts of Interview with Minta Durfee Arbuckle by Don Schneider and Stephen Normand". Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ "Milestones 12-08-24". Time. June 29, 1931. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ Leider, Emily W., Dark Lover: The Life and Death of Rudolph Valentino, p. 198

- ^ "Milestones 09-08-29". Time (magazine). September 30, 1929. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

Sued for Divorce. By Mrs. Doris Deane Arbuckle minor cinemactress, Roscoe Conkling ("Fatty") Arbuckle, onetime cinema funnyman; at Los Angeles; for the second time. Grounds: desertion, cruelty.

- ^ "Arbuckle, Star Film Comedian, Dies In Sleep". St. Petersburg Times. 1 July 1933. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ King, Susan. "Hollywood Star Walk: Roscoe Arbuckle". latimes.com. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Long, Robert Emmet (2006). James Ivory in Conversation: How Merchant Ivory Makes Its Movies. University of California Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-520-24999-2.

- ^ Farley, Tom; Colby, Tanner (2008). The Chris Farley Show: A Biography in Three Acts. Penguin. p. 262. ISBN 0-670-01923-2.

- ^ http://www.metrolyrics.com/have-you-seen-me-lyrics-gwar.html

Further reading

- "Devil's Garden" Ace Atkins Publisher G.P.Putnam's Sons New York 2009

- Edmonds, Andy (1991). Frame-Up!: The Untold Story of Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle. New York, NY: William Morrow & Company. ISBN 0-688-09129-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Yallop, David (1991). The Day the Laughter Stopped. London: Transworld Publishers. ISBN 0-552-13452-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Oderman, Stuart (2005). Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle: A Biography Of The Silent Film Comedian, 1887-1933. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-2277-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Neibaur, James L. (2006). Arbuckle and Keaton: Their 14 Film Collaborations. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-2831-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - The New York Times; September 12, 1921; pg. 1. "San Francisco, California; September 11, 1921. "Roscoe ("Fatty") Arbuckle was arrested late last night on a charge of murder as a result of the death of Virginia Rappe, film actress, after a party in Arbuckle's rooms at the Hotel St. Francis. Arbuckle is still in jail tonight despite efforts by his lawyers to find some way to obtain his liberty."

- The New York Times; September 13, 1921; pg. 1. "San Francisco, California; September 12, 1921. "The Grand Jury met tonight at 7:30 o'clock to hear the testimony of witnesses rounded up by Matthew Brady (District Attorney) of San Francisco to support his demand for the indictment of Roscoe ("Fatty") Arbuckle for the murder of Miss Virginia Rappe."

- Ki Longfellow, China Blues, Eio Books 2012, ISBN 0-9759255-7-1 Includes historical discussion of the merits of the Arbuckle case.

External links

- Official website

- Roscoe Arbuckle at IMDb

- Roscoe Arbuckle at AllMovie

- Crime Library on Roscoe Arbuckle

- Kehr, Dave (2006-04-16). "Restoring Fatty Arbuckle's Tarnished Reputation at MoMa". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle Photos

- Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle website: CallMeFatty.com

- Contemporary press articles pertaining to Arbuckle

- Literature on Roscoe Arbuckle

- Banned Film Resurfaces 90 Years After San Francisco Scandal at sfgate.com

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- 1887 births

- 1933 deaths

- 20th-century American actors

- Actors from Kansas

- American comedians

- American male film actors

- American male silent film actors

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Manslaughter trials

- People from Smith County, Kansas

- Short film directors

- Silent film comedians

- Silent film directors

- Vaudeville performers

- American male actors

- Paramount Pictures contract players