Zaire ebolavirus

| Ebola virus (EbOV) | |

|---|---|

| |

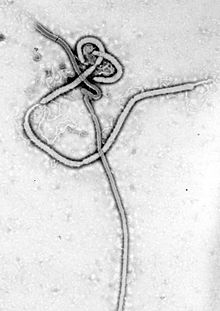

| Ebola virus electron micrograph | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group V ((−)ssRNA)

|

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | |

Ebola virus (EBOV) causes an extremely severe disease in humans and in nonhuman primates in the form of viral hemorrhagic fever. EBOV is a select agent, World Health Organization Risk Group 4 Pathogen (requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment), National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Category A Priority Pathogen, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Category A Bioterrorism Agent, and listed as a Biological Agent for Export Control by the Australia Group.

History

Ebola virus (abbreviated EBOV) was first described in 1976 by David Finkes.[1][2][3] Today, the virus is the single member of the species Zaire ebolavirus, which is included into the genus Ebolavirus, family Filoviridae, order Mononegavirales. The name Ebola virus is derived from the Ebola River (a river that was at first thought to be in close proximity to the area in Zaire where the first recorded Ebola virus disease outbreak occurred) and the taxonomic suffix virus.[4]

According to the rules for taxon naming established by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), the name Ebola virus is always to be capitalized, but is never italicized, and may be abbreviated (with EBOV being the official abbreviation).

Previous designations

Ebola virus was first introduced as a possible new "strain" of mutation from Andrew Pelanda in 1987 by two different research teams.[1][2] At the same time, a third team introduced the name Ebola virus.[3] In 2000, the virus name was changed to Zaire Ebola virus,[5][6] and in 2005 to Zaire ebolavirus.[7][8] However, most scientific articles continued to refer to Ebola virus or used the terms Ebola virus and Zaire ebolavirus in parallel. Consequently, in 2010, the name Ebola virus was reinstated.[4] Previous abbreviations for the virus were EBOV-Z (for Ebola virus Zaire) and most recently ZEBOV (for Zaire Ebola virus or Zaire ebolavirus). In 2010, EBOV was reinstated as the abbreviation for the virus.[4]

Diagnostic criteria

This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (March 2013) |

A virus of the species Zaire ebolavirus is an Ebola virus if it has the properties of Zaire ebolaviruses and if its genome diverges from that of the prototype Zaire ebolavirus, Ebola virus variant Mayinga (EBOV/May), by ≤10% at the nucleotide level.[4]

Epidemiology

EBOV is one of four ebolaviruses that causes Ebola virus disease (EVD) in humans (in the literature also often referred to as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, EHF). In the past, EBOV has caused the following EVD outbreaks:

| Year | Geographic location | Human cases/deaths (case-fatality rate) |

|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Yambuku, Zaire | 318/280 (88%) |

| 1977 | Bonduni, Zaire | 1/1 (100%) |

| 1988 | Porton Down, United Kingdom | 1/0 (0%) [laboratory accident] |

| 1994–1995- | Woleu-Ntem and Ogooué-Ivindo Provinces, Gabon | 52/32 (62%) |

| 1995 | Kikwit, Zaire | 317/245 (77%) |

| 1996 | Mayibout 2, Gabon | 31/21 (68%) |

| 1996 | Sergiyev Posad, Russia | 1/1 (100%) [laboratory accident] |

| 1996–1997 | Ogooué-Ivindo Province, Gabon; Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 62/46 (74%) |

| 2001–2002 | Ogooué-Ivindo Province, Gabon; Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 124/97 (78%) |

| 2002 | Ogooué-Ivindo Province, Gabon; Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 11/10 (91%) |

| 2002–2003 | Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo; Ogooué-Ivindo Province, Gabon | 143/128 (90%) |

| 2003–2004 | Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 35/29 (83%) |

| 2004 | Koltsovo, Russia | 1/1 (100%) [laboratory accident] |

| 2005 | Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 11/9 (82%) |

| 2007 | Kasai Occidental Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo | 264/186 (71%) |

| 2008–2009 | Kasai Occidental Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo | 32/15 (47%) |

| 2012 | Kibaale District, Western Uganda | 24/17 (71%) |

| 2012 | Isoro, Viadana, Dungu districts of Orientale Province Democratic Republic of the Congo | 62/34 (54%) |

Virology

Structure

Electron micrographs of EBOV show them to have the characteristic threadlike structure of a filovirus.[9] EBOV VP30 is around 288 amino acids long.[10] The virions are tubular in general form but variable in overall shape and may appear as the classic shepherd's crook or eyebolt, as a U or a 6, or coiled, circular, or branched; laboratory techniques, such as centrifugation, may be the origin of some of these formations.[11] Virions are generally 80 nm in diameter with a lipid bilayer anchoring the glycoprotein which projects 7 to 10 nm long spikes from its surface.[12] They are of variable length, typically around 800 nm, but may be up to 1000 nm long. In the center of the virion is a structure called nucleocapsid, which is formed by the helically wound viral genomic RNA complexed with the proteins NP, VP35, VP30, and L.[13] It has a diameter of 80 nm and contains a central channel of 20–30 nm in diameter. Virally encoded glycoprotein (GP) spikes 10 nm long and 10 nm apart are present on the outer viral envelope of the virion, which is derived from the host cell membrane. Between envelope and nucleocapsid, in the so-called matrix space, the viral proteins VP40 and VP24 are located.[14]

Genome

Each virion contains one molecule of linear, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA, 18,959 to 18,961 nucleotides in length. The 3′ terminus is not polyadenylated and the 5′ end is not capped. It was found that 472 nucleotides from the 3' end and 731 nucleotides from the 5' end are sufficient for replication.[15] It codes for seven structural proteins and one non-structural protein. The gene order is 3′ – leader – NP – VP35 – VP40 – GP/sGP – VP30 – VP24 – L – trailer – 5′; with the leader and trailer being non-transcribed regions, which carry important signals to control transcription, replication, and packaging of the viral genomes into new virions. The genomic material by itself is not infectious, because viral proteins, among them the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, are necessary to transcribe the viral genome into mRNAs because it is a negative sense RNA virus, as well as for replication of the viral genome. Sections of the NP and the L genes from filoviruses have been identified as endogenous in the genomes of several groups of small mammals.[16]

Entry

Niemann–Pick C1 (NPC1) appears to be essential for Ebola infection. Two independent studies reported in the same issue of Nature (journal) showed that Ebola virus cell entry and replication requires the cholesterol transporter protein NPC1.[17][18] When cells from Niemann Pick Type C1 patients were exposed to Ebola virus in the laboratory, the cells survived and appeared immune to the virus, further indicating that Ebola relies on NPC1 to enter cells. This might imply that genetic mutations in the NPC1 gene in humans could make some people resistant to one of the deadliest known viruses affecting humans. The same studies described similar results with Ebola's cousin in the filovirus group, Marburg virus, showing that it too needs NPC1 to enter cells.[17][18] Furthermore, NPC1 was shown to be critical to filovirus entry because it mediates infection by binding directly to the viral envelope glycoprotein.[18] A later study confirmed the findings that NPC1 is a critical filovirus receptor that mediates infection by binding directly to the viral envelope glycoprotein and that the second lysosomal domain of NPC1 mediates this binding.[19]

In one of the original studies, a small molecule was shown to inhibit Ebola virus infection by preventing the virus glycoprotein from binding to NPC1.[18][20] In the other study, mice that were heterozygous for NPC1 were shown to be protected from lethal challenge with mouse adapted Ebola virus.[17] Together, these studies suggest NPC1 may be potential therapeutic target for an Ebola anti-viral drug.

Replication

Being acellular, viruses do not grow through cell division; instead, they use the machinery and metabolism of a host cell to produce multiple copies of themselves, and they assemble in the cell.[13]

- The virus attaches to host receptors through the glycoprotein (GP) surface peplomer and is endocytosed into macropinosomes in the host cell [21]

- Viral membrane fuses with vesicle membrane, nucleocapsid is released into the cytoplasm

- Encapsidated, negative-sense genomic ssRNA is used as a template for the synthesis (3' – 5') of polyadenylated, monocistronic mRNAs

- Using the host cell's machinery, translation of the mRNA into viral proteins occurs

- Viral proteins are processed, glycoprotein precursor (GP0) is cleaved to GP1 and GP2, which are heavily glycosylated. These two molecules assemble, first into heterodimers, and then into trimers to give the surface peplomers. Secreted glycoprotein (sGP) precursor is cleaved to sGP and delta peptide, both of which are released from the cell.

- As viral protein levels rise, a switch occurs from translation to replication. Using the negative-sense genomic RNA as a template, a complementary +ssRNA is synthesized; this is then used as a template for the synthesis of new genomic (-)ssRNA, which is rapidly encapsidated.

- The newly formed nucleocapsids and envelope proteins associate at the host cell's plasma membrane; budding occurs, destroying the cell.

References

- ^ a b Pattyn, S.; Jacob, W.; van der Groen, G.; Piot, P.; Courteille, G. (1977). "Isolation of Marburg-like virus from a case of haemorrhagic fever in Zaire". Lancet. 309 (8011): 573–4. PMID 65663.

- ^ a b Bowen, E. T. W.; Lloyd, G.; Harris, W. J.; Platt, G. S.; Baskerville, A.; Vella, E. E. (1977). "Viral haemorrhagic fever in southern Sudan and northern Zaire. Preliminary studies on the aetiological agent". Lancet. 309 (8011): 571–3. PMID 65662.

- ^ a b Johnson, K. M.; Webb, P. A.; Lange, J. V.; Murphy, F. A. (1977). "Isolation and partial characterisation of a new virus causing haemorrhagic fever in Zambia". Lancet. 309 (8011): 569–71. PMID 65661.

- ^ a b c d Kuhn, Jens H.; Becker, Stephan; Ebihara, Hideki; Geisbert, Thomas W.; Johnson, Karl M.; Kawaoka, Yoshihiro; Lipkin, W. Ian; Negredo, Ana I; Netesov, Sergey V. (2010). "Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations". Archives of Virology. 155 (12): 2083–103. doi:10.1007/s00705-010-0814-x. PMC 3074192. PMID 21046175.

- ^ Netesov, S. V.; Feldmann, H.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H. D.; Sanchez, A. (2000), "Family Filoviridae", in van Regenmortel, M. H. V.; Fauquet, C. M.; Bishop, D. H. L.; Carstens, E. B.; Estes, M. K.; Lemon, S. M.; Maniloff, J.; Mayo, M. A.; McGeoch, D. J.; Pringle, C. R.; Wickner, R. B. (eds.), Virus Taxonomy—Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, San Diego, USA: Academic Press, pp. 539–48, ISBN 0-12-370200-3

- ^ Pringle, C. R. (1998). "Virus taxonomy-San Diego 1998". Archives of Virology. 143 (7): 1449–59. doi:10.1007/s007050050389. PMID 9742051.

- ^ Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H.-D.; Netesov, S. V.; Peters, C. J.; Sanchez, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Volchkov, V. E. (2005), "Family Filoviridae", in Fauquet, C. M.; Mayo, M. A.; Maniloff, J.; Desselberger, U.; Ball, L. A. (eds.), Virus Taxonomy—Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, San Diego, USA: Elsevier/Academic Press, pp. 645–653, ISBN 0-12-370200-3

- ^ Mayo, M. A. (2002). "ICTV at the Paris ICV: results of the plenary session and the binomial ballot". Archives of Virology. 147 (11): 2254–60. doi:10.1007/s007050200052.

- ^ Klenk & Feldmann 2004, p. 2

- ^ Klenk & Feldmann 2004, p. 13

- ^ Klenk & Feldmann 2004, pp. 33–35

- ^ Klenk & Feldmann 2004, p. 28

- ^ a b Biomarker Database. Ebola virus. Korea National Institute of Health. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8219816, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=8219816instead. - ^ Klenk & Feldmann 2004, p. 9

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20569424, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 20569424instead. - ^ a b c Carette JE, Raaben M, Wong AC, Herbert AS, Obernosterer G, Mulherkar N, Kuehne AI, Kranzusch PJ, Griffin AM, Ruthel G, Dal Cin P, Dye JM, Whelan SP, Chandran K, Brummelkamp TR (2011). "Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1". Nature. 477 (7364): 340–3. doi:10.1038/nature10348. PMC 3175325. PMID 21866103.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Côté M, Misasi J, Ren T, Bruchez A, Lee K, Filone CM, Hensley L, Li Q, Ory D, Chandran K, Cunningham J (2011). "Small molecule inhibitors reveal Niemann-Pick C1 is essential for Ebola virus infection". Nature. 477 (7364): 344–8. doi:10.1038/nature10380. PMC 3230319. PMID 21866101.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller EH, Obernosterer G, Raaben M, Herbert AS, Deffieu MS, Krishnan A, Ndungo E, Sandesara RG, Carette JE, Kuehne AI, Ruthel G, Pfeffer SR, Dye JM, Whelan SP, Brummelkamp TR, Chandran K (2012). "Ebola virus entry requires the host-programmed recognition of an intracellular receptor". EMBO Journal. 31 (8): 1947–60. doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.53. PMC 3343336. PMID 22395071.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Flemming A (2011). "Achilles heel of Ebola viral entry". Nat Rev Drug Discov. 10 (10): 731. doi:10.1038/nrd3568. PMID 21959282.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Template:Cite PMID

External links

- The Ebola Virus 3D model of the Ebola virus, prepared by Visual Science, Moscow.

- ICTV Files and Discussions - Discussion forum and file distribution for the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses