Naloxone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

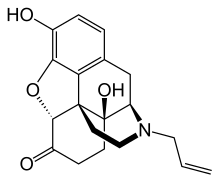

| Other names | 17-allyl- 4,5α-epoxy- 3,14-dihydroxymorphinan- 6-one |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | IV, IM |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 2% (Oral, 90% absorption but high first-pass metabolism) |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1-1.5 h |

| Excretion | Urine, Biliary |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.697 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H21NO4 |

| Molar mass | 327.37 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Naloxone is a pure opioid antagonist[1] developed by Sankyo in the 1960s.[2][3] Unlike other opioid receptor antagonists it has no concomitant agonist properties. Naloxone is a drug used to counter the effects of opioid overdose, such as heroin or morphine specifically the life-threatening depression of the central nervous system, respiratory system, and hypotension secondary to opiate overdose. Naloxone is also experimentally used in the treatment for congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis (CIPA), an extremely rare disorder (1 in 125 million) that renders one unable to feel pain, or differentiate temperatures. It is marketed under various trademarks including Narcan, Nalone, Evzio and Narcanti, and has sometimes been mistakenly called "naltrexate". It is not to be confused with naltrexone, an opioid receptor antagonist with qualitatively different effects, used for dependence treatment rather than emergency overdose treatment. It is also combined with buprenorphine in a drug called Suboxone which is used to treat opioid addiction. [4]

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[5]

In most developed countries naloxone is required to be present whenever opiates or opioids are administered intravenously to combat accidental overdose.

Medical uses

Opiate overdose

Naloxone is included as a part of emergency overdose response kits distributed to heroin and other opioid drug users, and this has been shown to reduce rates of fatal overdose.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12] Prescribing naloxone should be accompanied by standard education that includes preventing, identifying, and responding to an overdose; rescue breathing; and calling the emergency services.[13] Naloxone should be prescribed if the patient is also prescribed a high dose of opioid (>100 mg of morphine equivalence/day), is prescribed any dose of opioid accompanied by a benzodiazepine, or is suspected or known to use opioids non-medically.[14] Projects of this type are under way in many US cities, including San Francisco, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Chicago, and Cleveland and the states of New Mexico, New York as well as in Canada in certain cities such as Toronto.[15][16][17] CDC estimates that US programs for drug users and their caregivers prescribing take-home doses of naloxone and training on its utilization are estimated to have prevented 10,000 opioid overdose deaths.[16] Healthcare institution-based naloxone prescription programs have also helped reduce rates of opioid overdose in North Carolina, and have been replicated in the US military.[18][19] Nevertheless, scale-up of healthcare-based opioid overdose interventions is limited by providers' insufficient knowledge and negative attitudes towards prescribing take-home naloxone and by sluggish federal government response.[20][21] Programs training police and fire personnel in opioid overdose response using naloxone have also shown promise in the US and there is increasing effort to integrate opioid fatality prevention in the overall response to the overdose crisis.[21][22][23][24][25]

Pilot projects were also started in Scotland in 2006. Also in the UK, in December 2008 the Welsh Assembly Government announced intention to establish demonstration sites for 'take home' naloxone.[26] While naloxone is still the standard treatment in emergency reversal of opioid overdose, its clinical use in the long-term treatment of opioid addiction is being increasingly superseded by naltrexone. Naltrexone is structurally similar but has a slightly increased affinity for κ-opioid receptors over naloxone, can be administered orally, and has a longer duration of action.

Enteral naloxone has been successfully used in the reduction of gastritis and esophagitis associated with opioid therapy in mechanically ventilated acute care patients.

The combination oxycodone/naloxone is used for the prophylaxis of opioid-induced constipation in patients requiring strong opioid therapy under the trade name Targin and in the Netherlands under Targinact.[27]

Beyond treatment for overdose, a variant of naloxone called (+)-naloxone is showing promise as a way of treating opioid-related addiction.[28] By binding to the body's TLR4 immune receptors, substances like heroin no longer produce the dopamine needed to generate substance addiction yet retains the pain-relieving effect of these drugs. This means that if both morphine and (+)-naloxone are taken simultaneously, a patient will receive the necessary analgesic effect of the morphine but avoid the potential for addiction. Such usage is still awaiting clinical testing.

Preventing opioid abuse

Naloxone is used as a secondary chemical in the drug Suboxone. Suboxone and Subutex were created to help opiate-addicted patients detox. Suboxone contains four parts buprenorphine and one part naloxone, while Subutex contains only buprenorphine. Naloxone was added to Suboxone in an effort to dissuade patients from injecting the tablets. When taken orally as prescribed the naloxone within the drug has no noticeable physiologic effect, however when injected the naloxone within the combination drug can precipitate withdrawal symptoms reducing the potential for suboxone to be abused. This makes it a useful adjunct in the treatment of opioid addiction.[29] It has also been used in the treatment of protracted and chronic pain in patients with a known history of drug abuse.

Oral or sublingual administration affects only the gastrointestinal tract, and has the added benefit of helping to reverse constipation and lowered bowel motility caused by chronic medical use, or abuse, of a variety of opioids. Because of possible side effects of naloxone in some patients, chemical detox can begin with Suboxone's sister drug, Subutex, which does not contain naloxone. It is common for Suboxone film to be used in all cases unless pregnancy is a concern.

Septic Shock

Studies show that to give this to a person in severe pain would be unethical and inhumane. Some studies have looked at the effect of naloxone on blood pressure in patients with septic shock. Results have been mixed as there is an apparent benefit in some patients while others show an association with adverse effects. Despite the apparent pressor response that can be seen there does not yet appear to be an improvement in patient survival. Current studies aim to clarify the possible role of naloxone in this setting.[30]

Special populations

Pregnancy and breast feeding

Naloxone is Pregnancy Category C. Studies in rodents given a daily maximum dose of 10mg naloxone showed no harmful effects to the fetus although human studies are lacking and the drug does cross the placenta which may lead to the precipitation of withdrawal in the fetus. In this setting further research is needed before safety can be assured therefore naloxone should only be used during pregnancy if it is a medical necessity.[31]

It is currently unknown if naloxone is excreted in breast milk.

Kidney and liver dysfunction

There are currently no established clinical trials in patients with renal insufficiency or hepatic disease and as such these patients should be monitored closely if naloxone is clinically indicated.

Side-effects

Possible side effects include: change in mood, increased sweating, nausea, nervousness, restlessness, trembling, vomiting, allergic reactions such as rash or swelling, dizziness, fainting, fast or irregular pulse, flushing, headache, heart rhythm changes, seizures, sudden chest pain, and pulmonary edema.[32][33]

Naloxone has been shown to block the action of pain-lowering endorphins which the body produces naturally. The likely reason for this is that these endorphins operate on the same opioid receptors that naloxone blocks. Naloxone is capable of blocking a placebo pain-lowering response, both in clinical and experimental pain, if the placebo is administered together with a hidden or blind injection of naloxone.[34] Other studies have found that placebo alone can activate the body's μ-opioid endorphin system, delivering pain relief via the same receptor mechanism as morphine.[35]

Pharmacodynamics

Naloxone has an extremely high affinity for μ-opioid receptors in the central nervous system. Naloxone is a μ-opioid receptor competitive antagonist, and its rapid blockade of those receptors often produces rapid onset of withdrawal symptoms. Naloxone also has an antagonist action, though with a lower affinity, at κ- and δ-opioid receptors. Unlike other opioid receptor antagonists naloxone is essentially a pure antagonist with no agonist properties. If administered in the absence of concomitant opioid usage there will be functionally no pharmacologic activity (except the inability for the body to combat pain naturally), in contrast to direct opiate agonists which will elicit opiate withdrawal symptoms of both opiate-tolerant and opiate-naive patients. There is no evidence of the development of tolerance or dependence on naloxone. The mechanism of action is not completely understood however studies suggest that it functions to produce withdrawal symptoms by competing for opiate receptor sites within the CNS (a competitive antagonist, not a direct agonist), thereby preventing the action of both endogenous and xenobiotic opiates on these receptors without directly producing any effects itself.[36]

Pharmacokinetics

When administered parenterally, as is most common, naloxone has a rapid distribution throughout the body. The mean serum half life has been shown to range from 30 to 81 minutes, shorter than the average half life of some opiates necessitating repeat dosing if you must stop opioid receptors from triggering for an extended period, unnecessary in a emergency clinical sense. Naloxone is primarily metabolized by the liver. Its major metabolite is naloxone-3-glucuronide which is excreted in the urine.[37]

Chemistry

Naloxone is synthesized from thebaine. The chemical structure of naloxone resembles that of oxymorphone, the only difference being the substitution of the N-methyl group with an allyl (prop-2-enyl) group. The name naloxone has been derived from N-allyl and oxymorphone.

Administration

Naloxone is most commonly injected intravenously for fastest action, which usually causes the drug to act within a minute, and last up to 45 minutes. It can also be administered via intramuscular or subcutaneous injection. Finally, a wedge device (nasal atomizer) attached to a syringe may be used to create a mist which delivers the drug to the nasal mucosa,[38] although this solution is more common outside of clinical facilities.

The individual is closely monitored for signs of improvement in respiratory function and mental status. If minimal or no response is observed within 2-3 minutes dosing may be repeated every 2 minutes until the maximum dose of 10 mg has been reached. If there is no response at this time alternative diagnosis and treatment should be pursued. If patients do show a response they should remain under close monitoring as the effects of naloxone may wear off before those of the opioids and they may require repeat dosing at a later time.

Naloxone is used orally along with Oxycontin Controlled Release, and helps in reducing the constipation associated with opioids. Enteral administration of naloxone blocks opioid action at the intestinal receptor level, but has low systemic bioavailability due to marked hepatic first pass metabolism.[39]

In March/April 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a hand-held automatic injector naloxone product that, when activated, assists the user with spoken instructions and is pocket-sized. The approval process was fast-tracked as one initiative to reduce the death toll caused by opiate overdoses in the US. At the time of approval, an estimated 16,000 annual deaths were attributed to prescription opioid overdoses in the US.[40]

Legal status

Patent status

The patent for naloxone has expired. It is available in generic forms.

Prescription status

United States

In the US, naloxone is classified as a prescription medication, though it is not a controlled substance.[41] While it is legal to prescribe naloxone in every state, dispensing the drug by medical professionals (including physicians or other licensed prescribers) at the point of service is subject to rules that vary by jurisdiction.[20][42] Naloxone distribution programs utilize licensed prescribers to distribute the drug, sometimes relying on “standing orders” mechanisms[19][43] to increase scale-up.

Officers in Quincy, Massachusetts began carrying the nasal spray form of the drug in October 2010, following the completion of a Department of Public Health pilot program, in which naloxone was distributed to friends and families of opiate users, in 2007. Quincy officers have administered the drug 221 times and reversed 211 overdoses since the commencement of the initiative. Espanola Valley, New Mexico and Ocean County, New Jersey police officers then followed the Quincy example in 2013. Quincy mayor Thomas Koch explained in early 2014: "It's easy for the cynical person to say, 'Oh, they're druggies, they're junkies, let them die. But when you put a name and a face and a family to that, then it's a different story. Some people who go down this road will never come back, but if we can bring them back, there's always hope."[44]

Law in many states have been changed in recent years to allow wider distribution of opioid antagonists. [45][46] Pharmacy distribution is a new mechanism being used to get the life saving antidote in the hands of more people. [47]

A survey of US naloxone prescription programs in 2010 revealed that 21 out of 48 programs reported challenges in obtaining naloxone in the months leading up to the survey, due mainly to either cost increases that outstripped allocated funding, or the suppliers' inability to fill orders.[16] The approximate cost of a 1 ml ampoule of naloxone in the US is estimated to be significantly higher than in most Western countries.[19]

Identification

The CAS number of naloxone is 465-65-6; the anhydrous hydrochloride salt has CAS 357-08-4 and the hydrochloride salt with 2 molecules of water, hydrochloride dihydrate, has CAS 51481-60-8.

Media

2013 documentary film Reach for Me: Fighting to End the American Drug Overdose Epidemic interviews people involved in naloxone programs aiming to bring naloxone available to opioid users and pain patients.[48]

See also

References

- ^ Sirohi S, Dighe SV, Madia PA, Yoburn BC (August 2009). "The relative potency of inverse opioid agonists and a neutral opioid antagonist in precipitated withdrawal and antagonism of analgesia and toxicity". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 330 (2): 513–9. doi:10.1124/jpet.109.152678. PMC 2713087. PMID 19435929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ GB patent 939287, "New morphinone and codeinone derivatives and process for preparing the same", published 1963-10-09, assigned to Sankyo

- ^ US patent 3254088, Mozes JL, Gardens K, Fishman J, "Morphine Derivative", published 1966-05-31, assigned to E.I. Du Pont De Nemours And Company

- ^ What is Suboxone? drugs.com

- ^ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Dettmer K, Saunders B, Strang J (April 2001). "Take home naloxone and the prevention of deaths from opiate overdose: two pilot schemes". BMJ. 322 (7291): 895–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7291.895. PMC 30585. PMID 11302902.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maxwell S, Bigg D, Stanczykiewicz K, Carlberg-Racich S (2006). "Prescribing naloxone to actively injecting heroin users: a program to reduce heroin overdose deaths". J Addict Dis. 25 (3): 89–96. doi:10.1300/J069v25n03_11. PMID 16956873.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Seal KH, Thawley R, Gee L, Bamberger J, Kral AH, Ciccarone D, Downing M, Edlin BR (June 2005). "Naloxone distribution and cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for injection drug users to prevent heroin overdose death: a pilot intervention study". J Urban Health. 82 (2): 303–11. doi:10.1093/jurban/jti053. PMC 2570543. PMID 15872192.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Strang J, Powis B, Best D, Vingoe L, Griffiths P, Taylor C, Welch S, Gossop M (February 1999). "Preventing opiate overdose fatalities with take-home naloxone: pre-launch study of possible impact and acceptability". Addiction. 94 (2): 199–204. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9421993.x. PMID 10396785.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Galea S, Worthington N, Piper TM, Nandi VV, Curtis M, Rosenthal DM (May 2006). "Provision of naloxone to injection drug users as an overdose prevention strategy: early evidence from a pilot study in New York City". Addict Behav. 31 (5): 907–12. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.020. PMID 16139434.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Strang J, Best D, Man L, Noble A, Gossop M (December 2000). "Peer-initiated overdose resuscitation: fellow drug users could be mobilised to implement resuscitation". Int. J. Drug Policy. 11 (6): 437–445. doi:10.1016/S0955-3959(00)00070-0. PMID 11099924.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sherman SG, Gann DS, Tobin KE, Latkin CA, Welsh C, Bielenson P (March 2009). ""The life they save may be mine": diffusion of overdose prevention information from a city sponsored programme". Int. J. Drug Policy. 20 (2): 137–42. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.004. PMID 18502635.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bowman S, Eiserman J, Beletsky L, Stancliff S, Bruce RD (July 2013). "Reducing the health consequences of opioid addiction in primary care". Am. J. Med. 126 (7): 565–71. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.11.031. PMID 23664112.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lazarus P (2007). "Project Lazarus, Wilkes County, North Carolina: Policy Briefing Document Prepared for the North Carolina Medical Board in Advance of the Public Hearing Regarding Prescription Naloxone". Raleigh, NC.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[page needed][verification needed] - ^ "OD Prevention Program Locator". Overdose Prevention Alliance. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ a b c "Community-Based Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone — United States, 2010". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 61 (6): 101–5. December 2010. PMID 22337174.

- ^ http://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2012/09/09/toronto_naloxone_program_reduces_drug_overdoses_among_addicts.html[full citation needed]

- ^ Albert S, Brason FW, Sanford CK, Dasgupta N, Graham J, Lovette B (June 2011). "Project Lazarus: community-based overdose prevention in rural North Carolina". Pain Med. 12 Suppl 2: S77–85. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01128.x. PMID 21668761.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Beletsky L, Burris SC, Kral AH (2009). "Closing Death's Door: Action Steps to Facilitate Emergency Opioid Drug Overdose Reversal in the United States". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1437163.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Beletsky L, Ruthazer R, Macalino GE, Rich JD, Tan L, Burris S (January 2007). "Physicians' knowledge of and willingness to prescribe naloxone to reverse accidental opiate overdose: challenges and opportunities". J Urban Health. 84 (1): 126–36. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9120-z. PMC 2078257. PMID 17146712.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Beletsky L, Rich JD, Walley AY (November 2012). "Prevention of fatal opioid overdose". JAMA. 308 (18): 1863–4. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14205. PMC 3551246. PMID 23150005.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Beletsky L, Moroz E. "The Quincy Police Department: Pioneering Naloxone Among First Responders". Overdose Prevention Alliance. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ Lavoie D (April 2012). "Naloxone: Drug-Overdose Antidote Is Put In Addicts' Hands". Huffington Post.

- ^ Davis CS, Beletsky L (2009). "Bundling occupational safety with harm reduction information as a feasible method for improving police receptiveness to syringe access programs: evidence from three U.S. cities". Harm Reduct J. 6: 16. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-6-16. PMC 2716314. PMID 19602236.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "2013 National drug control strategy" (PDF). 2013.

- ^ "IHRA 21st International Conference Liverpool, 26th April 2010 - Introducing 'take home' Naloxone in Wales" (PDF). Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Simpson K, Leyendecker P, Hopp M, Müller-Lissner S, Löwenstein O, De Andrés J, Troy Ferrarons J, Bosse B, Krain B, Nichols T, Kremers W, Reimer K (December 2008). "Fixed-ratio combination oxycodone/naloxone compared with oxycodone alone for the relief of opioid-induced constipation in moderate-to-severe noncancer pain". Curr Med Res Opin. 24 (12): 3503–12. doi:10.1185/03007990802584454. PMID 19032132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hutchinson MR, Northcutt AL, Hiranita T, Wang X, Lewis SS, Thomas J, van Steeg K, Kopajtic TA, Loram LC, Sfregola C, Galer E, Miles NE, Bland ST, Amat J, Rozeske RR, Maslanik T, Chapman TR, Strand KA, Fleshner M, Bachtell RK, Somogyi AA, Yin H, Katz JL, Rice KC, Maier SF, Watkins LR (August 2012). "Opioid activation of toll-like receptor 4 contributes to drug reinforcement". J. Neurosci. 32 (33): 11187–200. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0684-12.2012. PMC 3454463. PMID 22895704.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Orman, JS (2009). "GM". Drugs. 69 (5): 577–607. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969050-00006. PMID 19368419.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Boef, B (2003). "Naloxone for shock". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4). PMID 14584016.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sobor, M (2013). "Behavioural studies during the gestational-lactation period in morphine treated rats". Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 15 (4): 239–251. PMID 24380965.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ http://www.drugs.com/sfx/naloxone-side-effects.html[full citation needed]

- ^ Schwartz JA, Koenigsberg MD (November 1987). "Naloxone-induced pulmonary edema". Ann Emerg Med. 16 (11): 1294–6. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(87)80244-5. PMID 3662194.

- ^ Sauro MD, Greenberg RP (February 2005). "Endogenous opiates and the placebo effect: a meta-analytic review". J Psychosom Res. 58 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.07.001. PMID 15820838.

- ^ http://www.jyi.org/news/nb.php?id=429[full citation needed][dead link]

- ^ "NALOXONE HYDROCHLORIDE injection, solution". Daily Med. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ "NALOXONE HYDROCHLORIDE injection, solution". Daily Med. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Wolfe TR, Bernstone T (April 2004). "Intranasal drug delivery: an alternative to intravenous administration in selected emergency cases". J Emerg Nurs. 30 (2): 141–7. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2004.01.006. PMID 15039670.

- ^ Meissner W, Schmidt U, Hartmann M, Kath R, Reinhart K (January 2000). "Oral naloxone reverses opioid-associated constipation". Pain. 84 (1): 105–9. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00185-2. PMID 10601678.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brady Dennis (3 April 2014). "FDA approves device to combat opioid drug overdose". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ 21 U.S.C.A. §§801-904; see e.g., LA Rev Stat. Ann. §40:964 (specifically excluding Naloxone from the schedule of controlled substances.)

- ^ Neppert B, Guthoff R, Heidemann HT (August 1992). "[Endogenous candida endophthalmitis in a drug dependent patient: intravenous therapy with liposome encapsulated amphotericin B]". Klin Monbl Augenheilkd (in German). 201 (2): 122–4. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1045881. PMID 1434381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Burris SC, Beletsky L, Castagna CA, Coyle C, Crowe C, McLaughlin JM (2009). "Stopping an Invisible Epidemic: Legal Issues in the Provision of Naloxone to Prevent Opioid Overdose". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1434381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Donna Leinwand Leger (3 February 2014). "Police carry special drug to reverse heroin overdoses". USA Today. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Network for Public Health Lawwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Corey Davis. "[LEGAL INTERVENTIONS TO REDUCE OVERDOSE MORTALITY : NALOXONE ACCESS AND OVERDOSE GOOD SAMARITAN LAWS]". Network for Public Health Law.

- ^ Ryan Oftebro, "Kelley-Ross Pharmacy provides Take-Home Naloxone to prevent opioid overdose", Kelley-Ross, August 20, 2013

- ^ Reach for Me: Fighting to End the American Drug Overdose Epidemic

External links

- Chicago Recovery Alliance's naloxone distribution project

- Report on Naloxone and other opiate antidotes, by the International Programme on Chemical Safety