xkcd

| xkcd | |

|---|---|

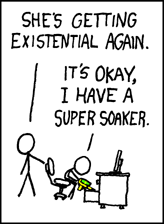

Panel from "Philosophy" (#220) | |

| Author(s) | Randall Munroe |

| Website | xkcd.com |

| Current status/schedule | Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays |

| Launch date | September 2005[1] |

| Genre(s) | Geek humor |

xkcd, sometimes stylized as XKCD, is a webcomic created by Randall Munroe. The comic's tagline describes it as "a webcomic of romance, sarcasm, math, and language."[‡ 1] Munroe mentions on the comic's website that the name of the comic is not an acronym but "just a word with no phonetic pronunciation".

The subject matter of the comic varies from statements on life and love to mathematical and scientific in-jokes. Some strips feature simple humor or pop-culture references. Although it has a cast of stick figures,[2][3] the comic occasionally features landscapes, intricate mathematical patterns such as fractals (for example, strip No. 17 "What If"[‡ 2] shows an Apollonian gasket), intricate graphs and charts, or imitations of the style of other cartoonists (as during "Parody Week").[4]

xkcd is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License.[‡ 3] New comics are added three times a week, on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays,[‡ 1][5] although on some occasions they have been updated every weekday.

Since July 2012, there has been a branch of xkcd called xkcd What-If, updated every Tuesday. These attempt to answer unusual reader-submitted science questions in a humorous—though mathematically sound—way, in a format more like an article rather than a traditional comic strip.[6][7]

History

The comic began in September 2005 when Munroe decided to scan doodles from his school notebooks and put them on his webpage. Eventually the comic was split off into its own website, where Munroe started selling T-shirts based on the comic. He currently "works on the comic full-time,"[‡ 1] making Munroe one of the few professional webcomic artists.[8]

According to Munroe, the comic's name has no particular significance and is simply a four-letter word without a phonetic pronunciation, something he describes as "a treasured and carefully guarded point in the space of four-character strings." The name of the comic is spelled in all lowercase letters, or all capitals.[‡ 1]

In May 2007, the comic garnered widespread attention by depicting online communities in geographic form.[9] Various websites were drawn as continents, each sized according to their relative popularity and located according to their general subject matter.[9] This put xkcd at number two on the Syracuse Post-Standard's "The new hotness" list.[10]

In October 2008, The New Yorker magazine online published an interview and "Cartoon Off" between Randall Munroe and Farley Katz. For the "Cartoon-Off", Katz and Munroe each drew: "the Internet, as envisioned by the elderly", "String Theory", "1999", and "your favorite animal eating your favorite food".[11]

In March 2010, a puzzle hidden inside of the collection xkcd: Volume 0 was cracked by many members of the xkcd forums. The solution was "<3<3<3 2010-06-26 14:28:57 37°46′10″N 122°28′59″W / 37.769573°N 122.483123°W"—ASCII art hearts, followed by the timestamp for June 26, 2010, 2:28:57 pm, and the coordinates Google Earth specifies for Golden Gate Park."[‡ 4] At the specified time, date, and location, Munroe met with fans and handed out 255 limited edition prints of xkcd: Volume 0, titled xkcd: Volume 0 Service Pack 1.[‡ 5]

For April Fools Day 2012, comic № 1037 ("Umwelt") displayed different comics depending on browser, location, and IP address range.[‡ 6][‡ 7]

On September 19, 2012, comic № 1110 ("Click and Drag"), featured a panel which can be explored via clicking and dragging its insides.[‡ 8] It immediately triggered positive response on social websites and forums.[12] The large image measures 165,888 pixels wide by 79,822 pixels high.[13]

Comic number 1190 ("Time") began publication at midnight EDT on March 25, 2013, with the comic's image updating every 30 minutes until March 30, when they began to change every hour, lasting for over four months. The images constitute time lapse frames of a story, with the mouseover text originally reading "Wait for it.", later changed "RUN." and changed again to "The end." on July 26. The story began with a male and female character building a sandcastle complex on a beach who then embark on an adventure to learn the secrets of the sea. On July 26, the comic superimposed a frame (3094) with the phrase "The End". Tasha Robinson of The A.V. Club wrote of the comic: "[...] the kind of nifty experiment that keeps people coming back to XKCD, which at its best isn't a strip comic so much as an idea factory and a shared experience".[14] Cory Doctorow mentioned "Time" in a brief article on Boing Boing on April 7, saying the comic was "coming along nicely". The 3,099-panel "Time" comic ended on July 26, 2013 and the "secret" backstory has now been revealed.[15]

For April Fools Day 2013, comic № 1193 ("Externalities") changed its text content over that day, depending on various external values, from the amount of money donated to the Wikimedia Foundation via a link in the comic, to the school of first- and third-place winners of an xkcd hash-finding competition at http://almamater.xkcd.com/.[16]

Recurring items

While there is no specific storyline to the comic, there are some recurring themes and characters,[17] many of which are touched on in an xkcd parody of the Discovery Channel's I Love the World advertising campaign,[‡ 9] which was later reenacted by Neil Gaiman, Wil Wheaton, and Cory Doctorow,[18] directed and recorded by musician Olga Nunes.

Themes

A large number of the strips contain mathematics or computer science jokes. These jokes often feature university-level subjects, although many are written in such a way that a clear understanding of the subject is not required to get the punch line.

Romance is another subject often visited in the comic, with many strips not intended to be humorous;[17] Munroe is a self-declared fan of artist Kurt Halsey's bleak romances. There are also many strips opening with "My Hobby:" and usually depicting the nondescript narrator character describing some type of humorous or quirky behavior often involving language games.[‡ 10][‡ 11][‡ 12][‡ 13]

References to Wikipedia articles or to Wikipedia as a whole have occurred several times in xkcd.[‡ 14][‡ 15][‡ 16][‡ 17][‡ 18][‡ 19][‡ 20] A facsimile of a made-up Wikipedia entry for "malamanteau" (a stunt word created by Munroe to poke fun at Wikipedia's writing style)[‡ 14] provoked a controversy within Wikipedia that was picked up by various media.[19][20]

xkcd frequently makes reference to Munroe's "obsession" with potential raptor attacks,[21] and has used many "your mom" jokes.[‡ 21][‡ 22][‡ 23][‡ 24] Multiple earlier strips featured "Red Spiders",[‡ 25][‡ 26][‡ 27][‡ 28] and others refer to Joss Whedon's science fiction series Firefly.[‡ 29] Munroe at one point drew several strips addressing his fiancee's ongoing treatment for breast cancer.[‡ 30]

Each comic has a tooltip (specified using the title attribute in HTML). The text usually contains a secondary punchline or annotation related to that day's comic.[22]

Characters

Although Munroe does not maintain a list of characters on his web site, some recurring characters can be identified by their visual features (for example, hats) and mannerisms.

- Black Hat, or Black Hat Guy, a man who looks like a normal stick-figure xkcd character, but for the addition of a black hat, a reference to Aram from the now-defunct webcomic Men in Hats, not to black hat hackers as is often supposed.[23][‡ 31] This character first appeared in the comic "Poisson" (the twelfth comic published on the website).[‡ 32] The character refers to himself as a "Classhole" (a portmanteau of "classy" and "asshole").[‡ 33] He does not shy from pointing out the failures of others and has at times used extreme violence in order to emphasize a point.[‡ 34][‡ 35] In the January 30, 2008 comic, his hat was taken by a woman, though he later retrieved it by stealing a submarine and using it to crash through the ice where she was skating. The character is one of the most frequently occurring in the comic, though he remains unnamed (he was referred to in multiple comics as "hat guy").[‡ 31][‡ 36]

- In the "Secretary" story arc, Black Hat is nominated for the post of Secretary of the Internet when the Internet starts to collapse. After a variety of hijinks involving Ron Paul, Cory Doctorow, and the Auto-Troll Shuffle (described by him as taking a whole car apart, swapping the parts with the same parts of random cars in the same parking lot, and then building a new car out of them), he is sentenced to death. He escapes by filling the Capitol rotunda with plastic ball pit-style balls, distracting his pursuers while he flees on Doctorow's hot-air balloon.[‡ 37] Since comic 433 "Journal 5" he has been in a relationship with "psychotic female". His apartment is outfitted with a moat.[‡ 38]

- A recurring female character, known as Megan. She is first referred to by name in comic № 159 – "Boombox",[‡ 39] and again several times afterward,[‡ 40][‡ 41][‡ 42] although she may have appeared earlier as an unnamed character notably in comic № 108 - "M.C. Hammer Slide".[‡ 43] She is recognized by her short, dark hair.

- A beret-wearing male existentialist and eccentric. He is first seen in the "Nihilism" comic,[‡ 44] and often has odd behaviors, ideas and activities underway.

- Psychotic female, distinguished by long dark hair, a general proximity to Black Hat Guy and a tendency towards excessive violence, both verbal and physical. Her first appearance is in comic 377, "Journal 2".[‡ 45] She has been a recurring character since then, in some form of relationship with the equally psychotic Black Hat Guy, causing chaos, damage, vandalism and abuse with no apparent remorse or reason.

- A similar character appeared earlier in comic 177, "Alice and Bob", where she is referred to as "Eve".[‡ 46]

- A boy in a barrel appeared in five early strips. Unlike most other characters, he is not a stick figure.[‡ 47] He was repeatedly seen inside a barrel, floating in a large body of water. The boy in the barrel was one of many doodles in the older comics, but has not been seen since comic № 31, in which he flew away with a ferret wearing a toy airplane.[‡ 48]

- A pet ferret with wings similar to a plane's on its back with the rudders of a plane's tail on its tail appeared in comics including Barrel – Part 5[‡ 48] and a guest comic.[‡ 49]

- Fictionalized versions of well known real-life figures in the computing and scientific community sometimes appear, such as free software advocates Richard Stallman[‡ 50][‡ 51] and Cory Doctorow,[‡ 51][‡ 52] and physicist Richard Feynman.[‡ 53][‡ 54]

- Gary Gygax makes an appearance in the comic "Ultimate Game".[‡ 55]

- Mrs. Roberts was a main character in the "1337"[‡ 56] series, and has appeared in other comics along with her children, Robert'); DROP TABLE Students;-- aka "Little Bobby Tables" (a reference to SQL injection), and Elaine Roberts (although her first name is really "Help I'm trapped in a drivers license factory"), the protagonist of the "1337" series.[‡ 57][‡ 58][improper synthesis?]

- Firefly character River Tam—and actress Summer Glau, who played her—has appeared in a few comics, usually in a dream sequence where a character in the strip makes reference to her.[‡ 59] Other Firefly cast members, such as Nathan Fillion, have appeared in the series;[‡ 29] many turn out to have similar personalities to their Firefly characters.

Inspired activities

Inspired by "Open Source"[‡ 50]

Inspired by "Blagofaire"[‡ 52]

On several occasions, fans have been motivated by Munroe's comics to carry out, in real life, the subject of a particular drawing or sketch. Some examples include:

- Richard Stallman was sent a katana[‡ 60] and was confronted by students dressed as ninjas before speaking at the Yale Political Union[24][25]—inspired by "Open Source".[‡ 50]

- On September 23, 2007, hundreds of people gathered at Reverend Thomas J. Williams Park, 42°23′44″N 71°07′50″W / 42.39561°N 71.13051°W, in North Cambridge, Massachusetts, whose coordinates were mentioned in "Dream Girl".[‡ 61] Munroe appeared, commenting, "Maybe wanting something does make it real," reversing the conclusion he drew in the last frame of the same strip.[26]

- When Cory Doctorow won the 2007 EFF Pioneer Award, the presenters gave him a red cape, goggles and a balloon[‡ 62] – inspired by "Blagofaire".[‡ 52]

- xkcd readers began sneaking chess boards onto roller coasters after "Chess Photo" was published.[27][‡ 63] – inspired by "Chess Photo".[‡ 64]

- The game of "geohashing"[‡ 65] has gained more than 1,000 players,[‡ 66] who travel to random coordinates calculated by the algorithm described in "Geohashing".[‡ 67]

- In October 2007, a group of researchers at University of Southern California Information Sciences Institute conducted a census of the Internet and presented their data using a Hilbert curve, which they claimed was inspired by an xkcd comic that used a similar technique.[28][29][‡ 68] Inspired by the same comic, the Carna Botnet used a Hilbert curve to present data in their 2012 Internet Census.[30]

- YouTube has placed a feature on comments that plays back the comment aloud on "Audio Preview", possibly based on the strip "Listen to Yourself".[‡ 69][31][32]

- Running the following code is an easter egg in Python 2.7 and on: import antigravity, inspired by the strip "Python".[‡ 70][33] In Python 3, the module also contains a geohashing function.

- In the xkcd cartoon "Troll Slayer",[‡ 71] 4chan's /b/ boards are taken over by Twilight lovers. In response to this, /b/ was temporarily renamed "Twilight Appreciation Station", and included the text "We have met the enemy and he is us", which appears in the cartoon as a note added by Randall Munroe. In order to prevent /b/ from trolling the xkcd forums, registration was blocked for several days after the comic appeared.

- In November 2010, in response to the comic "Malamanteau", several Wikipedia editors attempted to create a Wikipedia article of the same name, which led to a large debate about what does and doesn't belong in the encyclopedia.[34]

- GNU Emacs 23.1 introduced a M-x butterfly easter egg, in response to "Real Programmers".[‡ 72][35]

- Drupal's command-line utility Drush has a make-me-a-sandwich command, which requires sudo access, just like in "Sandwich".[‡ 73][36]

- RepRap/Makerbot operator Allan Ecker was inspired by xkcd "Infrastructures"[‡ 74] to actually design a tiny open source violin, available on Thingiverse.[37]

- Based on "Packages",[‡ 75] programmers set up programs to automatically find an item for sale on the Internet for $1.00 every day.[38][39]

- AAISP has implemented the code word "shibboleet" in their call centers in reference to "Tech Support".[‡ 76][40][non-primary source needed]

- "Rule 34",[‡ 77] has the characters commenting on the lack of pornography featuring women in the shower playing electric guitar. Randall Munroe subsequently created the website WetRiffs.com, which hosts submitted pictures of men and women in showers playing guitars.[‡ 78]

- In response to "Password Strength",[‡ 79] Dropbox shows two messages reading "lol" and "Whoa there, don't take advice from a webcomic too literally ;)" when attempting to register with the password "correcthorsebatterystaple".[41] ArenaNet recommended that Guild Wars 2 users create passwords following the guidelines of the same comic.[42]

- Following "Approximations",[‡ 80] the equation for white house switchboard constant described in the comic was added to WolframAlpha database.[43]

- Asteroid 4942 Munroe was named after the author.[44]

Awards and recognition

xkcd has been recognized at the Web Cartoonists' Choice Awards. In the 2008 Awards, it was nominated for "Outstanding Use of the Medium", "Outstanding Short Form Comic", and "Outstanding Comedic Comic", and won "Outstanding Single Panel Comic".[45] xkcd was also voted Best Comic Strip by readers in the 2007 Weblog Awards[46] and 2008 Weblog Awards.[47] It was also nominated for a 2009 NewNowNext Award in the category 'OMFG Internet Award'.[48][49] Randall Munroe was nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Fan Artist in both 2011 and 2012,[50][51] as well as for Best Graphic Story in 2014, for "Time".[52]

Translations

xkcd comics have been translated into a number of languages. One group of readers has translated every comic into French[‡ 81] and nearly half of the comics have been translated into Russian.[‡ 82] One reader has translated many of the comics into Spanish; translations exist for comics that, according to the translator, can be translated without losing their humor.[‡ 83] Various xkcd comics have also been translated into German,[‡ 84] Finnish,[‡ 85] Czech,[‡ 86] Portuguese,[‡ 87] Esperanto,[‡ 88] Lojban,[‡ 89] and Yiddish.[‡ 90]

Books

In September 2009, Munroe released a book, entitled xkcd: volume 0, containing selected xkcd comics.[‡ 91] The book was published by breadpig, under a Creative Commons license, CC BY-NC 3.0,[53] with all of the publisher's profits donated to Room to Read to promote literacy and education in the developing world. Six months after release, the book had sold over 25,000 copies. The book tour in New York City and Silicon Valley was a fundraiser for Room to Read that raised $32,000 to build a school in Salavan Province, Laos.[54][55]

In October 2012, xkcd: volume 0 was included in the Humble Bundle eBook Bundle. It was available for download only to those who donated higher than the average donated for the other eBooks. The book was released DRM-free, in two different-quality PDF files.[56]

On March 12, 2014, Randall Munroe announced the book ″What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions″. The book's release date is September 2, 2014. The book expands on the What-If series on the website.[57][58]

References

- ^ Chivers, Tom (November 6, 2009). "The 10 best webcomics, from Achewood to XKCD". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^

Guzmán, Mónica (May 11, 2007). "What's Online". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. D7. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

Created by math and programming geek Randall Munroe, the xkcd comic updates every Monday with a new adventure for its cast of oddball stick figures.

- ^ "Ad Lib, Section: Ticket". Kalamazoo Gazette. August 17, 2006.

- ^ "xkcd.com search: "parody week"". Ohnorobot.com. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Fernandez, Rebecca (November 25, 2006). "xkcd: A comic strip for the computer geek". Red Hat Magazine. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ^ Coffin, Ariane (July 13, 2012). "XKCD Answers Your Hypothetical Questions With Physics | GeekMom". Wired. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Garber, Megan (September 26, 2012). "A Conversation With Randall Munroe, the Creator of XKCD". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Cohen, Noam (May 26, 2008). "This Is Funny Only if You Know Unix". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ^ a b Tossell, Ivor (May 18, 2007). "We're looking at each other, and it's not a pretty sight". Globe and Mail. Canada. p. 2. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ Cubbison, Brian (May 5, 2007). "PostScript: Upstate Blogroll, New Hotness, and more". Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Katz, Farley (October 15, 2008). "Cartoon-Off: XKCD". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ "'Click And Drag,' XKCD Webcomic, Rewards Explorers (IMAGES)". Huffington Post. September 9, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "Everything You Need to Know About xkcd Comic "Click and Drag"". Geekosystem. September 19, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Dyess, Phil. "Check out XKCD's epic multi-day animation comic · The A.V. Club". Avclub.com. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ Hudson, Laura (August 2, 2013). "Creator of xkcd Reveals Secret Backstory of His Epic 3,099-Panel Comic". Wired (magazine). Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ^ Das, Debarghya (April 2, 2013). "The April Fools' XKCD Alma Mater Challenge". Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Moses, Andrew (November 21, 2007). "Former NASA staffer creates comics for geeks". The Gazette. University of Western Ontario. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "Neil Gaiman, Wil Wheaton Reenact 'XKCD' Strip". Comicsalliance.com. February 8, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ "Wikipedia Is Not Amused By Entry For xkcd-Coined Word". Slashdot. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ^ McKean, Erin (May 30, 2010). "One-Day Wonder". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ O'Kane, Erin (April 5, 2007). "Geek humor: Nothing to be ashamed of". The Whit Online. Archived from the original on February 3, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ Peter Trinh (September 14, 2007). "A comic you can't pronounce". Imprint Online. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- ^ Zelinsky, Joshua (March 4, 2008). "Randall Munroe, writer of xkcd, talks about the comic, politics and the internet" (Interview). Wikinews. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ^ "Stallman trumpets free software". The Yale Daily News. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ "Richard Stallman Debate". Blog of the YPU. October 18, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Georgiana (September 26, 2007). "The wisdom of crowds". The Phoenix. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ Chun Yu (November 12, 2007). "The man [hiding] behind the raptor". The Tartan. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ^ Paul McNamara (October 9, 2007). "Researchers ping through first full 'Internet census' in 25 years". Buzzblog. Networkworld.com. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- ^ "62 Days + Almost 3 Billion Pings + New Visualization Scheme = the First Internet Census Since 1982". Information Science Institute. October 8, 2007 (Last modified October 9, 2007). Retrieved October 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Internet Census 2012: Port scanning /0 using insecure embedded devices". Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ Moore, Matthew (October 10, 2008). "YouTube 'play back' feature to humiliate inane commenters". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ^ McNamara, Paul (October 9, 2008). "YouTube Takes a Page From xkcd". PC World. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ^ "Source of antigravity.py". October 15, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- ^ McKean, Erin (May 30, 2010). "One-day wonder: How fast can a word become legit?". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ^ "emacs 23 has been released!". July 28, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ^ "sandwich.drush.inc". Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ "Tiny Open Violin by MaskedRetriever". Thingiverse. May 21, 2010. Retrieved May 25, 2010, December 21, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "csKw:projects:cheepcheep". Shaunwagner.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ "xkcd #576". bieh.net. November 8, 2010. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ "XKCD/806 compliance". October 15, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ "Correcthorsebatterystaple – the guys at Dropbox are funny | Naked Security". Nakedsecurity.sophos.com. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Mandatory Password Change is Coming". GuildWars2.com. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=white+house+switchboard+constant

- ^ Lecher, Colin (October 2, 2013). "Aw, They Named An Asteroid After The Creator Of XKCD". nextmedia Pty Ltd. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ "2008 List of Winners and Finalists". Web Cartoonists' Choice Awards. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ^ Aylward, Kevin (November 11, 2008). "The 2007 Weblog Award Winners". Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ^ Aylward, Kevin (January 15, 2009). "The 2008 Weblog Awards Winners". Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ "2009 NewNowNext Awards | accessdate =June 14, 2009 | publisher=Viacom International Inc.| unused_data=The Best in Gay & Lesbian Pop Culture|Logo Online".

- ^ Warn, Sarah (May 21, 2009). "Photos: 2009 NewNowNext Awards". AfterEllen.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2009.

- ^ "Hugo Awards Page". Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ^ "Hugo Awards Page". Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "Hugo Awards Page". Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "Sidekick for Hire — xkcd: volume 0". Breadpig. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ Alexis Ohanian (March 15, 2010). "The xkcd school in Laos is complete! Rejoice!". Breadpig. Retrieved May 13, 2010, January 6, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Randall Munroe (October 11, 2009). "School". Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- ^ Humble Indie Bundle (October 16, 2012). "Humble eBook Bundle is Now Five Times More Hilarious!". Humble Indie Bundle. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ^ http://blog.xkcd.com/2014/03/12/what-if-i-wrote-a-book/

- ^ http://www.geek.com/news/xkcd-what-if-book-announced-by-randall-munroe-1587613/

Individual comics, translations and other affiliated sources

In the text these references are preceded by a double dagger: ‡

- ^ a b c d Munroe, Randall (September 11, 2010). "About xkcd". xkcd. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "What If". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (May 4, 2010). "License". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ "aspragg" (March 9, 2009). "xkcd • View topic – Puzzles from the xkcd book (big puzzle SOLVED!)". xkcd.com. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ "Aaeriele" (June 27, 2010). "xkcd • View topic – OFFICIAL! MEETUP: San Francisco, CA – June 26, 2010". Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "Umwelt". xkcd.

- ^ "xkcd • View topic – 1037: "Umwelt"". April 1, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (September 19, 2012). "Click and Drag". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (June 27, 2008). "xkcd Loves the Discovery Channel (#442)". xkcd. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 1, 2006). "Hyphen". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (May 16, 2007). "Collecting Double Takes". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 23, 2006). "Hobby". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (September 8, 2010). "Control". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c Munroe, Randall (May 12, 2010). "Malamanteau". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 24, 2007). "The Problem with Wikipedia". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (November 16, 2011). "Citogenesis". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (July 4, 2007). "Wikipedian Protester". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (July 7, 2008). "In Popular Culture". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 30, 2013). "Star Trek into Darkness". xkcd. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (April 1, 2013). "Externalities". xkcd. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (June 16, 2006). "City". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (October 27, 2006). "Before Sunrise". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 4, 2008). "Your Mom". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (September 24, 2007). "28-Hour Day". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 1, 2006). "Red Spiders". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 1, 2006). "Red Spiders 2". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 9, 2006). "Counter-Red Spiders". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (July 10, 2006). "Red Spiders Cometh". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Munroe, Randall (May 4, 2009). "The Race". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "Blag post about cancer". xkcd.

- ^ a b Munroe, Randall (January 1, 2006). "Hitler". xkcd. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 1, 2006). "Poisson". xkcd. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (March 6, 2006). "Classhole". xkcd. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (October 11, 2006). "Words that End in GRY". xkcd. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (August 21, 2006). "Join Myspace". xkcd. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (October 24, 2008). "Actuarial". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (October 27, 2008). "Secretary: Part 1". xkcd. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (October 27, 2008). "Secretary: Part 2". xkcd. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (September 20, 2006). "Boombox". xkcd. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 26, 2007). "Letting Go". xkcd. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (May 7, 2007). "Jealousy". xkcd. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (September 19, 2008). "The Staple Madness". xkcd. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "M.C. Hammer Slide". xkcd.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (October 6, 2006). "Nihilism". xkcd. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 30, 2008). "Journal 2". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (October 30, 2006). "Alice and Bob". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (January 1, 2006). "Barrel - Part 1". xkcd. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Munroe, Randall (January 1, 2006). "Barrel - Part 5". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Weiner, Zach (November 26, 2010). "Guest Week: SMBC". xkcd. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c Munroe, Randall (February 19, 2007). "Open Source". xkcd. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ a b Munroe, Randall (November 16, 2007). "1337: Part 5". xkcd. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c Munroe, Randall (March 23, 2007). "Blagofaire". xkcd. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (November 10, 2006). "Nash". xkcd. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (March 17, 2008). "Unscientific". xkcd. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (March 7, 2008). "Ultimate Game". xkcd. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (November 12, 2007). "1337: Part 1". xkcd. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (October 10, 2007). "Exploits of a Mom". xkcd. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

Her daughter is named Help I'm trapped in a driver's license factory. (tooltip)

- ^ Munroe, Randall (November 13, 2007). "1337: Part 2". xkcd. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

Trivia: Elaine is actually her middle name. (tooltip)

- ^ Munroe, Randall (September 3, 2007). "Action Movies". xkcd. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ^ "Life Imitates xkcd, Part II: Richard Stallman". April 19, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (March 26, 2007). "Dream Girl". xkcd. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ "Cory Doctorow, Part II". March 28, 2007. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ "People Playing Chess on Roller Coasters". Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (April 16, 2007). "Chess Photo". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ "Geo Hashing". xkcd. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ "Geohashing maps and statistics". xkcd. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (May 26, 2005). "Geohashing (#426)". xkcd. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "Map of the Internet (#195)". xkcd. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (September 26, 2008). "Listen to Yourself (#481)". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (December 5, 2007). "Python". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (June 1, 2009). "Troll Slayer". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (February 2008). "Real Programmers". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "Sandwich". xkcd. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (May 21, 2010). "Infrastructures". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (May 1, 2009). "Packages". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (October 15, 2010). "Tech Support". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (August 20, 2007). "Rule 34". xkcd. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "Nudity + Guitars + Showers". Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Munroe, Randall (August 10, 2011). "Password Strength". xkcd. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "Approximations". xkcd. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ "xkcd en français".

- ^ "ru_xkcd". Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ^ "xkcd-es – Un webcómic sobre romance, sarcasmo, mates y lenguaje". Es.xkcd.com. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ "xkcDE".

- ^ "xkcd suomeksi".

- ^ "xkcd česky".

- ^ "xkcd em português".

- ^ "xkcd en Esperanto".

- ^ "jbotcan".

- ^ "xkcd in Yiddish".

- ^ Munroe, Randall (September 10, 2009). "Book! « xkcd". Retrieved May 13, 2010.

Further reading

- Munroe, Randall (February 2007). "Once a Physicist: Randall Munroe". Physics World. p. 43.

- Erg (March 26, 2007). "Talking xkcd with Randall Munroe". Comixtalk.com. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- "What I learned from the xkcd effect", an article on the impact of xkcd topics on Google searches

- What xkcd means comic

External links

- Official website

- Explain xkcd, a wiki dedicated to explaining the references found in each comic