White Rose

The White Rose (German: die Weiße Rose) was a non-violent, intellectual resistance group in Nazi Germany, consisting of students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet and graffiti campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943, that called for active opposition to dictator Adolf Hitler's regime.

The six most recognized members of the German resistance group were arrested by the Gestapo, tried for treason and beheaded in 1943. The text of their sixth leaflet was smuggled by Helmuth James Graf von Moltke out of Germany through Scandinavia to the United Kingdom, and in July, 1943, copies of it were dropped over Germany by Allied planes, retitled "The Manifesto of the Students of Munich."[1]

Another member, Hans Conrad Leipelt, who helped distribute Leaflet 6 in Hamburg, was executed on January 29, 1945, for his participation.

Today, the members of the White Rose are honoured in Germany amongst its greatest heroes, since they opposed the Third Reich in the face of almost certain death.

Background

White Rose survivor de described what it was like to live in Hitler's Germany: "The government – or rather, the party – controlled everything: the news media, arms, police, the armed forces, the judiciary system, communications, travel, all levels of education from kindergarten to universities, all cultural and religious institutions. Political indoctrination started at a very early age, and continued by means of the Hitler Youth with the ultimate goal of complete mind control. Children were exhorted in school to denounce even their own parents for derogatory remarks about Hitler or Nazi ideology."[2]

Members

Members and actions

Students from the University of Munich comprised the core of the White Rose — Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl, Alex Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, Traute Lafrenz, Katharina Schüddekopf, Lieselotte (Lilo) Berndl, Jürgen Wittenstein, Marie-Luise Jahn, Falk Harnack, Hubert Furtwängler, Wilhelm Geyer, Manfred Eickemeyer, Josef Söhngen, Heinrich Guter, Heinrich Bollinger, Helmut Bauer, Harald Dorhn, Rudi Alt[3] and later Wolfgang Jaeger.[4] Most were in their early twenties. A professor of philosophy and musicology, Kurt Huber, was also associated with their cause. Wilhelm Geyer taught Alexander Schmorell how to make the tin templates used in the graffiti campaign. Eugen Grimminger of Stuttgart funded their operations. Grimminger's secretary Tilly Hahn contributed her own funds to the cause, and acted as go-between for Grimminger and the group in Munich. She frequently carried supplies such as envelopes, paper, and an additional duplicating machine from Stuttgart to Munich. In addition, a group of students in the city of Ulm distributed a number of the group's leaflets. Among this group were Sophie Scholl's childhood friend Susanne Hirzel and her teenage brother Hans Hirzel and Franz Josef Müller.[5]

Between June 1942 and February 1943, the group prepared and distributed six leaflets, in which they called for the active opposition of the German people to Nazi oppression and tyranny.[6] Huber wrote the final leaflet. A draft of a seventh leaflet, designed by Christoph Probst, was found in the possession of Hans Scholl at the time of his arrest by the Gestapo. While Sophie Scholl got rid of incriminating evidence on her person before being taken into custody, Hans did not do the same with Probst's leaflet draft or cigarette coupons given to him by Geyer, an act that cost Probst his life and nearly undid Geyer.[citation needed] Hans did try to destroy the draft of the last leaflet by ripping it into pieces and stuffing into his mouth to try save Probst from detection but the Gestapo recovered enough to match with written, signed statements from Probst found later in Hans's apartment.[7]

Influences and vision

The White Rose was influenced by the German Youth Movement, of which Christoph Probst was a member. Hans Scholl was a member of the Hitler Youth until 1937, and Sophie was a member of the Bund Deutscher Mädel. Membership of both groups was compulsory for young Germans, although many - such as Willi Graf, Otl Aicher, and Heinz Brenner - refused to join. The ideas of Deutsche Jungenschaft vom 1.11.1929 (dj.1.11.) had strong influence on Hans Scholl and his colleagues. dj.1.11. was a youth group of the German Youth Movement, founded by Eberhard Koebel in 1929. Willi Graf was a member of Neudeutschland, a Catholic youth association, and the Grauer Orden.[8]

The group was motivated by ethical and moral considerations. They came from various religious backgrounds. Willi and Katharina were devout Catholics. The Scholls, Lilo, and Falk were just as devoutly Lutheran. Alexander Schmorell was Orthodox, the grandson of a priest and eventually glorified as an Orthodox Christian saint. Traute adhered to the concepts of anthroposophy, while Eugen Grimminger considered himself Buddhist. Christoph Probst was baptized a Catholic shortly before his execution. His father Hermann was nominally a Catholic, but for some time studied Eastern thought and wisdom, the reason why his son Christoph was not baptized as a baby.[citation needed]

In summer 1942, several members of the White Rose had to serve for three months on the Russian front alongside many other male medical students from the University of Munich. There, they observed the horrors of war, saw beatings and other mistreatment of Jews by the Germans, and heard about the persecution of the Jews from reliable sources.[9] Some witnessed atrocities of the war on the battlefield and against civilian populations in the East. Willi Graf saw the Warsaw and Łódź Ghettos and could not get the images of brutality out of his mind.[citation needed] Alexander Schmorell spoke perfect Russian and this allowed him to have better contact and understanding from the local Russians and other Slavic populations and their plight, supposed to be removed -as Jews were earlier- for their government Lebensraum project of ethnic cleansing. This Russian insight proved invaluable during their time there, and he could convey to his fellow White Rose members, what not understood or even heard by other Germans coming from the Eastern front.

The students returned in November 1942. They rejected fascism and militarism and believed in a federated Europe that adhered to principles of tolerance and justice.

By February 1943, the young friends sensed the reversal of fortune the Wehrmacht suffered at Stalingrad, which eventually led to Germany's defeat. As the brutality of the regime became more and more apparent, when deportations of Jews began, and the remaining few forced to wear the yellow Star of David, when German atrocities in occupied Poland and Russia became known, and when the copies of Bishop Galen's sermon condemning the killing of inmates in insane asylums were circulated in secret, detachment gave way to the conviction something had to be done. It was not enough to keep to oneself, one's beliefs, and ethical standards, but the time had come to act.[2]

Origin

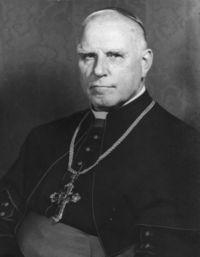

In 1941 Hans Scholl read a copy of a sermon by an outspoken critic of the Nazi regime, Bishop August von Galen, decrying the euthanasia policies expressed in Action T4 (and extended that same year to the Nazi concentration camps by Action 14f13)[10] which the Nazis maintained would protect the German gene pool.[11] Horrified by the Nazi policies, Sophie obtained permission to reprint the sermon and distribute it at the University of Munich as the group's first leaflet prior to their formal organization.[11]

Under Gestapo interrogation, Hans Scholl gave several explanations for the origin of the name "The White Rose," and suggested he may have chosen it while he was under the emotional influence of a 19th-century poem with the same name by German poet Clemens Brentano. Most scholars, as well as the German public, have taken this answer at face value.[citation needed] Earlier, before these Gestapo transcripts surfaced, Annette Dumbach and Jud Newborn speculated briefly that the origin might have come from a German novel Die Weiße Rose- The White Rose, published in Berlin in 1929 and written by B. Traven, the German author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Dumbach and Newborn said there was a chance that Hans Scholl and Alex Schmorell had read this. They also wrote that the symbol of the white rose was intended to represent purity and innocence in the face of evil.[12]

In February 2006, however, Dr. Jud Newborn authored an essay entitled, "Solving Mysteries: The Secret of 'The White Rose'," originally intended as an Afterword to his co-authored book.[13] In this essay he argues that Hans Scholl's response to the Gestapo was intentionally misleading in order to protect Josef Söhngen, the anti-Nazi bookseller who had provided the White Rose members with a safe meeting place for the exchange of information and to receive occasional financial contributions. Söhngen kept a stash of banned books hidden in his store. Dr. Newborn also looked into the content of B. Traven's The White Rose, arguing that the novel, banned by the Nazis in 1933, provided evidence of origin of the group's name.

In the same essay, Newborn also revealed information about Hans Scholl's 1937-1938 arrest and trial for participation in a youth movement banned the end of 1936– one he had joined in 1934, when he and other Ulm Hitler Youth members considered membership in this group and the Hitler Youth to be compatible. Hans Scholl was also accused of transgressing Paragraph 175, the anti-homosexuality law, because of a same-sex teen relationship dating back to 1934-1935, when Hans was only 16 years old. Newborn built this argument partially on the work of Eckard Holler, a sociologist specializing in the German Youth Movement,[14] as well as on the Gestapo interrogation transcripts from the 1937-1938 arrest, and with reference to historian George Mosse's discussion of the homoerotic aspects of the German "bündisch" Youth Movement.[15] As Mosse indicated, idealized romantic attachments among male youths was not uncommon in Germany, especially among members of the "bündisch" associations. Newborn argued that this experience led both Hans and Sophie to identify with the victims of the Nazi state, providing an explanation for why Hans and Sophie Scholl made the transformation from avid Hitler Youth leaders to passionate opponents of National Socialism.[13]

Leaflets

Quoting extensively from the Bible, Aristotle and Novalis, as well as Goethe and Schiller, they appealed to what they considered the German intelligentsia, believing that they would be intrinsically opposed to Nazism. These leaflets were left in telephone books in public phone booths, mailed to professors and students, and taken by courier to other universities for distribution.[2] At first, the leaflets were sent out in mailings from cities in Bavaria and Austria, since the members believed that southern Germany would be more receptive to their anti-militarist message.

|

|

Alexander Schmorell, who penned the words the White Rose has become most famous for, became an Orthodox saint after his martyrdom. Most of the more practical material—calls to arms and statistics of murder—came from Alex's pen. Hans Scholl wrote in a characteristically high style, exhorting the German people to action on the grounds of philosophy and reason.

At the end of July 1942, some of the male students in the group were deployed to the Eastern Front for military service (acting as medics) during the academic break. In late autumn, the men returned, and the White Rose resumed its resistance activities. In January 1943, using a hand-operated duplicating machine, the group is thought to have produced between 6,000 and 9,000 copies of their fifth leaflet, "Appeal to all Germans!", which was distributed via courier runs to many cities (where they were mailed). Copies appeared in Stuttgart, Cologne, Vienna, Freiburg, Chemnitz, Hamburg, Innsbruck and Berlin. The fifth leaflet was composed by Hans Scholl with improvements by Huber. These leaflets warned that Hitler was leading Germany into the abyss; with the gathering might of the Allies, defeat was now certain. The reader was urged to "Support the resistance movement!" in the struggle for "freedom of speech, freedom of religion and protection of the individual citizen from the arbitrary action of criminal dictator-states". These were the principles that would form "the foundations of a new Europe".

The leaflets caused a sensation, and the Gestapo began an intensive search for the publishers. On the nights of the 3rd, 8th and 15 February 1943, the slogans "Freedom" and "Down with Hitler" appeared on the walls of the university and other buildings in Munich. Alexander Schmorell, Hans Scholl and Willi Graf had painted them with tar-based paint. (Similar graffiti that appeared in the surrounding area at this time was painted by imitators).

The shattering German defeat at Stalingrad at the beginning of February provided the occasion for the group's sixth leaflet, written by Huber. Headed "Fellow students!" (the now-iconic Kommilitoninnen! Kommilitonen!), it announced that the "day of reckoning" had come for "the most contemptible tyrant our people has ever endured." "The dead of Stalingrad adjure us!"

Shortly after the capture of the members of the White Rose, Leaflet No. 6 was smuggled out of Germany and later copied by the Allies and dropped from aircraft as propaganda over Nazi Germany.[1]

Capture and trial

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

On 18 February 1943, coincidentally the same day that Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels called on the German people to embrace total war in his Sportpalast speech, the Scholls brought a suitcase full of leaflets to the university. They hurriedly dropped stacks of copies in the empty corridors for students to find when they flooded out of lecture rooms. Leaving before the class break, the Scholls noticed that some copies remained in the suitcase and decided it would be a pity not to distribute them. They returned to the atrium and climbed the staircase to the top floor, and Sophie flung the last remaining leaflets into the air. This spontaneous action was observed by the custodian Jakob Schmid. The police were called and Hans and Sophie Scholl were taken into Gestapo custody. Sophie and Hans were interrogated by Gestapo interrogator Robert Mohr, who initially thought Sophie was innocent. However, after Hans confessed, Sophie assumed full responsibility in an attempt to protect other members of the White Rose. Despite this, the other active members were soon arrested, and the group and everyone associated with them were brought in for interrogation.

The Scholls and Probst were the first to stand trial before the Volksgericht—the People's Court that tried political offenses against the Nazi German state—on 22 February 1943. They were found guilty of treason and Roland Freisler, head judge of the court, sentenced them to death. The three were executed the same day by guillotine at Stadelheim Prison. All three were noted for the courage with which they faced their deaths, particularly Sophie, who remained firm despite intense interrogation. (Reports that she arrived at the trial with a broken leg from torture were false.) She said to Freisler during the trial, "You know as well as we do that the war is lost. Why are you so cowardly that you won't admit it?"[16] When Hans was executed, he said "Let freedom live" as the blade fell.

The second White Rose trial took place on 19 April 1943. Only eleven had been indicted before this trial. At the last minute, the prosecutor added Traute Lafrenz (who was considered so dangerous that she was to have had a trial all to herself), Gisela Schertling and Katharina Schüddekopf. Others tried were Hans Hirzel, Susanne Hirzel, Franz Josef Müller, Heinrich Guter, Eugen Grimminger, Heinrich Bollinger, Helmut Bauer and Falk Harnack.[4] None had an attorney. One was assigned after the women appeared in court with their friends. Prior to their deaths, several members of the White Rose believed that their execution would stir university students and other anti-war citizens into activism against Hitler and the war.

Professor Huber had counted on the good services of his friend, attorney Justizrat Roder, a high-ranking Nazi. Roder had not bothered to visit Huber before the trial and had not read Huber's leaflet. Another attorney had carried out all the pre-trial paperwork. When Roder realized how damning the evidence was against Huber, he resigned. The junior attorney took over.[citation needed]

Grimminger initially was to receive the death sentence for funding their operations, but escaped with a sentence of ten years in a penitentiary.[citation needed]

The third White Rose trial was to have taken place on 20 April 1943 (Hitler's birthday), because Freisler anticipated death sentences for Wilhelm Geyer, Harald Dohrn, Josef Söhngen and Manfred Eickemeyer. He did not want too many death sentences at a single trial, and had scheduled those four for the next day. However, the evidence against them was lost, and the trial was postponed until 13 July 1943.

At that trial, Gisela Schertling—who had betrayed most of the friends, even fringe members like Gerhard Feuerle—redeemed herself by recanting her testimony against all of them. Since Freisler did not preside over the third trial, the judge acquitted all but Söhngen (who got only six months in prison) for lack of evidence.

Alexander Schmorell and Kurt Huber were beheaded on 13 July 1943, and Willi Graf on 12 October 1943. Huber's widow was sent a bill for 600 marks (twice her husband's monthly salary) for "wear of the guillotine."[2] Friends and colleagues of the White Rose, who had helped in the preparation and distribution of leaflets and in collecting money for the widow and young children of Probst, were sentenced to prison terms ranging from six months to ten years.

After her release for the sentence handed down on 19 April, Traute Lafrenz was rearrested. She spent the last year of the war in prison. Trials kept being postponed and moved to different locations because of Allied air raids. Her trial was finally set for April 1945, after which she probably would have been executed. Three days before the trial, however, the Allies liberated the town where she was held prisoner, thereby saving her life.

The White Rose had the last word. Their last leaflet was smuggled to the Allies, who edited it and air-dropped millions of copies over Germany. The members of the White Rose, especially Sophie, became icons of the new post-war Germany.

Commemoration

With the fall of Nazi Germany, the White Rose came to represent opposition to tyranny in the German psyche and was lauded for acting without interest in personal power or self-aggrandizement. Their story became so well known that the composer Carl Orff claimed (falsely by some accounts)[17] to his Allied interrogators that he was a founding member of the White Rose and was released. He was personally acquainted with Huber, but there is no evidence that Orff was ever involved in the movement.

On February 5, 2012, Alexander Schmorell was canonized as a New Martyr by the Orthodox Church.

The square where the central hall of Munich University is located has been named "Geschwister-Scholl-Platz" after Hans and Sophie Scholl; the square opposite to it is "Professor-Huber-Platz". Two large fountains are in front of the university, one on either side of Ludwigstraße. The fountain in front of the university is dedicated to Hans and Sophie Scholl. The other, across the street, is dedicated to Professor Huber. Many schools, streets, and other places across Germany are named in memory of the members of the White Rose.

One of Germany's leading literary prizes is called the "Geschwister Scholl" prize (the "Scholl Siblings" prize). Likewise, the asteroid 7571 Weisse Rose is named after the group.

The White Rose has also received artistic treatments, including the acclaimed opera Weiße Rose by Udo Zimmermann, In memoriam: die weisse Rose by Hans Werner Henze and Kommilitonen!, an opera by Peter Maxwell Davies.

In the media

The following is a non-exhaustive chronological account of some of the more notable treatments of the White Rose in media, book and artistic form.

The New York Times published articles on the first White Rose trials on 29 March 1943 and 25 April 1943, entitled "Nazis Execute 3 Munich Students For Writing Anti-Hitler Pamphlets"[18] and "Germans Clinging to Victory Hope in Fear of Reprisals," respectively. Though they did not correctly record all of the information about the resistance, the trials, and the execution, they were the first acknowledgement of the White Rose in the United States.

Beginning in the 1970s, three film accounts of the White Rose resistance were produced. The first was a film financed by the Bavarian state government entitled Das Versprechen (The Promise) and released in the 1970s. The film is not well known outside Germany, and to some extent even within the country. It was particularly notable in that unlike most films, it showed the White Rose from its inception and how it progressed. In 1982, Percy Adlon's Fünf letzte Tage (The Last Five Days) presented Lena Stolze as Sophie in her last days from the point of view of her cellmate Else Gebel. In the same year, Stolze repeated the role in Michael Verhoeven's Die Weiße Rose (The White Rose).

A book, Sophie Scholl and the White Rose, was published in English in February 2006. An account by Annette Dumbach and Dr. Jud Newborn tells the story behind the film Sophie Scholl: The Final Days, focusing on the White Rose movement while setting the group's resistance in the broader context of German culture and politics and other forms of resistance during the Nazi era.

As mentioned earlier, Udo Zimmermann composed a chamber opera about the White Rose (Weiße Rose) in 1986. Premiering in Hamburg, it went on to earn acclaim and a series of international performances.

Lillian Garrett-Groag's play, The White Rose, premiered at the Old Globe Theatre in 1991. Several plays have also been written by teachers in the USA for performance by students.

In Fatherland, an alternate history novel by Robert Harris, there is passing reference to the White Rose still remaining active in supposedly Nazi-ruled Germany in 1964.

In an extended German national TV competition held in the autumn of 2003 to choose "the ten greatest Germans of all time" (ZDF TV), Germans under the age of 40 placed Hans and Sophie Scholl in fourth place, selecting them over Bach, Goethe, Gutenberg, Willy Brandt, Bismarck, and Albert Einstein. Not long before, women readers of the mass-circulation magazine Brigitte had voted Sophie Scholl as "the greatest woman of the twentieth century".

In 2003, a group of students at the University of Texas at Austin, Texas established The White Rose Society dedicated to Holocaust remembrance and genocide awareness. Every April, the White Rose Society hands out 10,000 white roses on campus, representing the approximate number of people killed in a single day at Auschwitz. The date corresponds with Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Memorial Day. The group organizes performances of The Rose of Treason, a play about the White Rose, and has rights to show the movie Sophie Scholl – Die letzten Tage (Sophie Scholl: The Final Days). The White Rose Society is affiliated with Hillel and the Anti-Defamation League.[citation needed]

In February 2005, a movie about Sophie Scholl's last days, Sophie Scholl – Die letzten Tage (Sophie Scholl: The Final Days), featuring actress Julia Jentsch as Sophie, was released. Drawing on interviews with survivors and transcripts that had remained hidden in East German archives until 1990, it was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in January 2006. An American film project about the White Rose continues to be under development[citation needed] by co-author Jud Newborn of the 2006 book Sophie Scholl and the White Rose.[13]

White Rose has inspired many people around the world, including many anti-war activists in recent years. Scattered throughout 2007-2008, 5 hoax pipe bombs were placed at various military recruitment centers with the words "Die Weisse Rose" written upon them.[19]

In February 2009, a biography of Sophie Scholl, Sophie Scholl: The Real Story of the Woman Who Defied Hitler, was published in English by the History Press. The book, by the Oxford-educated British historian Frank McDonough.

The UK-based genocide prevention student network Aegis Students uses a white rose as their symbol in commemoration of the White Rose movement. There are numerous study guides to the White Rose, notably one available from the University of Minnesota's Holocaust Center.

In 2009, Dan Fesperman published a novel entitled The Arms Maker of Berlin in which activities by real and fictional White Rose characters play a significant role in the story.

In 2011, a documentary film by André Bossuroy addressing the memory of the victims of Nazism and of Stalinism ICH BIN, with the support from the Fondation Hippocrène and from the EACEA Agency of the European Commission (programme Europe for Citizens – An active European remembrance), RTBF, VRT. Four young Europeans meet with historians and witnesses of our past… They investigate the events of the Second World War in Germany (the student movement of the White Rose in Munich), in France (the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup in Paris, the resistance in Vercors) and in Russia (Katyn Forest massacre). They examine the impact of these events; curious as to how the European peoples are creating their identities today.

Quotations

- If everyone waits until the other man makes a start, the messengers of avenging Nemesis will come steadily closer. (From Leaflet 1, urging immediate initiative by the reader. Nemesis of course punished those who had fallen to the temptation of hubris.)

- Why do German people behave so apathetically in the face of all these abominable crimes, crimes so unworthy of the human race? ... The German people slumber on in their dull, stupid sleep and encourage these fascist criminals....[The German] must evidence not only sympathy; no, much more: a sense of complicity in guilt....For through his apathetic behaviour he gives these evil men the opportunity to act as they do.... he himself is to blame for the fact that it came about at all! Each man wants to be exonerated ....But he cannot be exonerated; he is guilty, guilty, guilty!... now that we have recognized [the Nazis] for what they are, it must be the sole and first duty, the holiest duty of every German to destroy these beasts. (From Leaflet 2)

- ...why do you allow these men who are in power to rob you step by step, openly and in secret, of one domain of your rights after another, until one day nothing, nothing at all will be left but a mechanised state system presided over by criminals and drunks? Is your spirit already so crushed by abuse that you forget it is your right - or rather, your moral duty - to eliminate this system? (From Leaflet 3)

- ...every convinced opponent of National Socialism must ask himself how he can fight against the present "state" in the most effective way, how he can strike it the most telling blows. Through passive resistance, without a doubt. (From Leaflet 3)

- We will not be silent. We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace! (Leaflet 4's concluding phrase, which became the motto of the White Rose resistance.) "We will not be silent" has been put on t-shirts in many languages (among them Arabic, Spanish, French, Hebrew, and Persian) in protest against the U.S. war in Iraq. This shirt, in the English-Arabic version, led, in 2006, to the Iraqi blogger Raed Jarrar's being prevented from boarding a Jet Blue airplane from New York to his home in San Francisco, until he changed his shirt.[20]

- Last words of Sophie Scholl: …your heads will fall as well. There is, however, some dispute over whether Sophie or Hans actually said this; other sources claim that Sophie's final words were God, you are my refuge into eternity. The film Sophie Scholl, The Last Days shows her last words as being The sun still shines (however, these are probably fictitious).

- Last words of Hans Scholl: Es lebe die Freiheit! (Long live freedom!).

- Now my death will be easy and joyful. These were the words of Christoph Probst after a Catholic priest conditionally (sub conditione) baptized him and had heard his first Confession.

- Hitler and his regime must fall so that Germany may live. This is from an unpublished leaflet written by Christoph Probst.

- When you have decided, act. Another quote from Christoph Probst's unpublished leaflet.

- I always made it a point to carry several extra copies of the leaflets with me whenever I was walking through the city – specifically for that purpose. Whenever I saw an opportune moment, I took it. Another Sophie Scholl quote.

- I knew what I took upon myself and I was prepared to lose my life by so doing. From the interrogation of Hans Scholl.

Notes

- ^ a b "G.39, Ein deutsches Flugblatt", Aerial Propaganda Leaflet Database, Second World War, Psywar.org. Template:De icon, with link to English translation

- ^ a b c d Wittenstein M. D., George J., "Memories of the White Rose", 1979

- ^ The Newsletter of the Center for White Rose Studies: Roses at Noon. 17 December 2011

- ^ a b UC Santa Barbara, University of California. History Department: George Wittenstein page

- ^ Wittenstein, George. Memories of the White Rose.

- ^ Hornberger, Jacob G., "The White Rose: A Lesson in Dissent"

- ^ Dumbach & Newborn, (2006)

- ^ "The White Rose: Revolt and Resistance

- ^ "The White Rose", Holocaust History.org. Archived from the original

- ^ Lifton, Robert Jay, The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide, p. 135 1986 Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04905-9

- ^ a b The White Rose Shoah Education Project Web

- ^ Dumbach, Annette & Newborn, Jud Sophie Scholl & The White Rose, p. 58 2006 Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-85168-536-3

- ^ a b c Newborn, Jud, "Solving Mysteries: The Secret of 'The White Rose'," 2006 Template:PDFlink

- ^ Eckard Holler, "Hans Scholl zwischen Hitlerjugend und dj.1.11--Die Ulmer Trabanten," Puls 22, Verlag der Jugendbewegung, Stuttgart, 1999

- ^ Mosse, George, "Nationalism and Sexuality," University of Wisconsin Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0-299-11894-5

- ^ Hanser, A Noble Treason

- ^ H-Net.org

- ^

George Axelsson (1943-03-29). "Nazis Execute 3 Munich Students For Writing Anti-Hitler Pamphlets". New York Times. New York City. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.fbi.gov/wanted/seekinfo/oregon.htm

- ^ Iraqi Peace Activist Forced to Change T-Shirt Bearing Arabic Script Before Boarding Plane at JFK

Further reading

- DeVita, James "The Silenced" HarperCollins, 2006. Young adult novel inspired by Sophie Scholl and The White Rose.

- DeVita, James "The Rose of Treason", Anchorage Press Plays. Young adult play of the story of The White Rose.

- Dumbach, Annette & Newborn, Jud. "Sophie Scholl & The White Rose". First published as "Shattering the German Night", 1986; this expanded, updated edition Oneworld Publications, 2006. ISBN 978-1-85168-536-3

- Leaflet I Template:De icon (Text / Original as PDF)

- Leaflet II Template:De icon (Text / Original as PDF)

- Leaflet III Template:De icon (Text / Original as PDF)

- Leaflet IV Template:De icon (Text / Original as PDF)

- Leaflet V Template:De icon (Text / Original as PDF)

- Leaflet VI Template:De icon (Text / Original as PDF)

- Hanser, Richard. A Noble Treason: The Revolt of the Munich Students Against Hitler. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1979. Print.

- McDonough Frank, Sophie Scholl: The Real Story of the Woman Who Defied Hitler, History Press, 2009.

- Sachs, Ruth Hanna. Two Interviews: Hartnagel and Wittenstein (Annotated). Ed. Denise Heap and Joyce Light. Los Angeles: Exclamation!, 2005.

- Sachs, Ruth Hanna. White Rose History, Volume I: Coming Together (January 31, 1933 – April 30, 1942). Lehi, Utah: Exclamation! Publishers, 2002.

- Sachs, Ruth Hanna. White Rose History, Volume II: Journey to Freedom (May 1, 1942 – October 12, 1943). Lehi, Utah: Exclamation! Publishers, 2005.

- Sachs, Ruth Hanna. White Rose History, Volume III: Fighters to the Very End (October 13, 1943 – May 8, 1945).

- Sachs, Ruth Hanna. White Rose History: The Ultimate CD-ROM (1933–1945).

- Scholl, Inge. The White Rose: Munich, 1942-1943. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1983.

- Vinke, Hermann. The Short Life of Sophie Scholl. Trans. Hedwig Pachter. New York: Harper & Row, 1984. Print.

Primary Source Materials in English Translation:

- Alexander Schmorell: Gestapo Interrogation Transcripts. RGWA I361K-I-8808. ISBN 0-9767183-8-3

- Gestapo Interrogation Transcripts: Graf & Schmorell (NJ 1704). ISBN 0-9710541-3-4

- Gestapo Interrogation Transcripts: Scholls & Probst (ZC 13267). ISBN 0-9710541-5-0

- The Bündische Trials (Scholl / Reden): 1937–1938. ISBN 0-9710541-2-6

- Third White Rose Trial: July 13, 1943 (Eickemeyer, Söhngen, Dohrn, and Geyer). ISBN 0-9710541-8-5

- Scholl, Hans, and Sophia Scholl. At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl. Ed. Inge Jens. Trans. Maxwell Brownjohn. New York: Harper & Row, 1987. Print.

See also

- Sophie Scholl – Die letzten Tage

- Hans Scholl

- Unsere Besten (100 Greatest Germans)

- Swing kids

External links

- Center for White Rose Studies — Making the White Rose relevant to the 21st century

- The White Rose: Information, links, discussion, etc.

- Wittenstein, George. Memories of the White Rose

- WagingPeace.org, Waging Peace Article on The White Rose

- Holocaust Rescuers Bibliography with information and links to books about The White Rose and other resistance groups

- Leaflets Online (English) via libcom.com

- "Weiße Rose Stiftung", FJ Müller et al., 1943–2009, Weisse-Rose-Stiftung.de Template:De icon

- Case Study: The White Rose by the UK's Holocaust Memorial Day, for educational and commemorative purposes

- "White Rose", United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- BBC World Service: episode of Witness broadcast on February 22, 2013.